The Image of Streetwalkers in Itzik Manger's and Debora Vogel's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baal Shem-Toy Ballads of Shimshon Meltzer

THE BAAL SHEM-TOY BALLADS OF SHIMSHON MELTZER by SHLOMO YANIV The literary ballad, as a form of narrative metric composition in which lyric, epic, and dramatic elements are conjoined and whose dominant mood is one of mystery and dread, drew its inspiration from European popular ballads rooted in oral tradition. Most literary ballads are written in a concentrated and highly charged heroic and tragic vein. But there are also those which are patterned on the model of Eastern European popular ballads, and these poems have on the whole a lyrical epic character, in which the horrific motifs ordinarily associated with the genre are mitigated. The European literary ballad made its way into modern Hebrew poetry during its early phase of development, which took place on European soil; and the type of balladic poem most favored among Hebrew poets was the heroico-tragic ballad, whose form was most fully realized in Hebrew in the work of Shaul Tchernichowsky. With the appearance in 1885 of Abba Constantin Shapiro's David melek yifrii.:>e/ f:tay veqayyii.m ("David King of Israel Lives"), the literary ballad modeled on the style of popular ballads was introduced into Hebrew poetry. This type of poem was subsequently taken up by David Frischmann, Jacob Kahan, and David Shimoni, although the form had only marginal significance in the work of these poets (Yaniv, 1986). 1 Among modern Hebrew poets it is Shimshon Meltzer who stands out for having dedicated himself to composing poems in the style of popular balladic verse. These he devoted primarily to Hasidic themes in which the figure and personality of Israel Baal Shem-Tov, the founder of Hasidism, play a prominent part. -

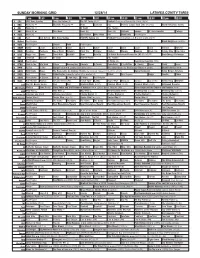

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

M-Ad Shines in Toronto

Volume 44, Issue 3 SUMMER 2013 A BULLETIN FOR EVERY BARBERSHOPPER IN THE MID-ATLANTIC DISTRICT M-AD SHINES IN TORONTO ALEXANDRIA MEDALS! DA CAPO maKES THE TOP 10 GImmE FOUR & THE GOOD OLD DAYS EARN TOP 10 COLLEGIATE BROTHERS IN HARMONY, VOICES OF GOTHam amONG TOP 10 IN THE WORLD WESTCHESTER WOWS CROWD WITH MIC-TEST ROUTINE ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT, FRANK THE DOG HIT TOP 20 UP ALL NIGHT KEEPS CROWD IN STITCHES CHORUS OF THE CHESAPEAKE, BLACK TIE AFFAIR GIVE STRONG PERFORmaNCES INSIDE: 2-6 OUR INTERNATIONAL COMPETITORS 7 YOU BE THE JUDGE 8-9 HARMONY COLLEGE EAST 10 YOUTH CamP ROCKS! 11 MONEY MATTERS 12-15 LOOKING BACK 16-19 DIVISION NEWS 20 CONTEST & JUDGING YOUTH IN HARMONY 21 TRUE NORTH GUIDING PRINCIPLES 23 CHORUS DIRECTOR DEVELOPMENT 24-26 YOUTH IN HARMONY 27-29 AROUND THE DISTRICT . AND MUCH, MUCH MORE! PHOTO CREDIT: Lorin May ANYTHING GOES! 3RD PLACE BRONZE MEDALIST ALEXANDRIA HARMONIZERS PULL OUT ALL THE STOPS ON STAGE IN TORONTO. INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION 2013: QUARTET CONTEST ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT, T.J. Carollo, Jeff Glemboski, Larry Bomback and Wayne Grimmer placed 12th. All photos courtesy of Dan Wright. To view more photos, go to www. flickr.com/photosbydanwright UP ALL NIGHT, John Ward, Cecil Brown, Dan Rowland and Joe Hunter placed 28th. DA CAPO, Ryan Griffith, Anthony Colosimo, Wayne FRANK THE Adams and Joe DOG, Tim Sawyer placed Knapp, Steve 10th. Kirsch, Tom Halley and Ross Trube placed 20th. MID’L ANTICS SUMMER 2013 pa g e 2 INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION 2013: COLLEGIATE QUARTETS THE GOOD OLD DAYS, Fernando Collado, Doug Carnes, Anthony Arpino, Edd Duran placed 10th. -

We Will Rock You”

“We Will Rock You” By Queen and Ben Elton At the Hippodrome Theatre through October 20 By Princess Appau WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS When one walks into the Hippodrome Theatre to view “We Will Rock You,” the common expectation is a compilation of classic rock and roll music held together by a simple plot. This jukebox musical, however, surpasses those expectations by entwining a powerful plot with clever updating of the original 2002 musical by Queen and Ben Elton. The playwright Elton has surrounded Queen’s songs with a plot that highlights the familiar conflict of our era: youths being sycophants to technology. This comic method is not only the key to the show’s success but also the antidote to any fear that the future could become this. The futuristic storyline is connected to many of Queen’s lyrics that foreshadow the youthful infatuation with technology and the monotonous lifestyle that results. This approach is emphasized by the use of a projector displaying programmed visuals of a futuristic setting throughout the show. The opening scene transitions into the Queen song “Radio Gaga,” which further affirms this theme. The scene includes a large projection of hundreds of youth, clones to the cast performing on stage. The human cast and virtual cast are clothed alike in identical white tops and shorts or skirts; they sing and dance in sublime unison, defining the setting of the show and foreshadowing the plot. Unlike most jukebox musicals the plot is not a biographical story of the performers whose music is featured. “We Will Rock You” is set 300 years in the future on the iPlanet when individuality and creativity are shunned and conformity reigns. -

Ballad of the Buried Life

Ballad of the Buried Life From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Ballad of the Buried Life rudolf hagelstange translated by herman salinger with an introduction by charles w. hoffman UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 38 Copyright © 1962 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Hagelstange, Rudolf. Ballad of the Buried Life. Translated by Herman Salinger. Chapel Hill: University of North Car- olina Press, 1962. doi: https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469658285_Hagel- stange Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Salinger, Herman. Title: Ballad of the buried life / by Herman Salinger. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 38. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1962] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. Identifiers: lccn unk81010792 | isbn 978-0-8078-8038-8 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5828-5 (ebook) Classification: lcc pd25 .n6 no. -

The Yiddishists

THE YIDDISHISTS OUR SERIES DELVES INTO THE TREASURES OF THE WORLD’S BIGGEST YIDDISH ARCHIVE AT YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH From top: Illustration from Kleyne Mentshelekh (Tiny Little People), a Yiddish adaptation of Gulliver’s Travels published in Poland, 1925. The caption reads, “With great effort I liberated my left hand.”; cover page for Kleyne Mentshelekh Manger was not the only 20th-century Yiddish-speaking Jew to take an interest in Swift’s 18th-century works. Between 1907 and 1939, there were at least five Yiddish translations and adaptations of Gulliver’s Travels published in the United States, Poland and Russia. One such edition, published in 1925 by Farlag Yudish, a publishing house that specialised in Yiddish translations of literary classics, appeared in their Kinder-bibliotek (Children’s Library) series alongside other beloved books such as Harriet Beecher GULLIVER IN YIDDISHLAND Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Edith Nesbit’s The Enchanted Castle and fairytales by the Jonathan Swift, Oscar Wilde and Samuel Beckett were just some brothers Grimm. Literature and journals THE YIDDISHISTS of the Anglo-Irish and Irish writers whose work was translated and for children and youth, both those written specifically in Yiddish and those translated adapted by 20th-century Yiddishists, says Stefanie Halpern into the language, were a lucrative branch of Yiddish publishing in the interwar n his 1942 poem ‘A Song of the Dean of Stella’s golden brooch, a reference to ‘A period. Such material became especially Jonathan Swift and the Yiddish Journal to Stella’, Swift’s 1766 work based important with the establishment of a IRhyme-maker Itzik Manger’, the poet on letters he sent to his real-life lover Yiddish secular school network across and playwright Itzik Manger imagines a Esther Johnson. -

Jewish Humor

Jewish Humor Jewish Humor: An Outcome of Historical Experience, Survival and Wisdom By Arie Sover Jewish Humor: An Outcome of Historical Experience, Survival and Wisdom By Arie Sover This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Arie Sover All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6447-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6447-3 With love to my parents, Clara (Zipkis) and Aurel Sober, and my grandmother, Fanny Zipkis: Holocaust survivors who bequeathed their offspring with a passion for life and lots of humor. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. xii Preface ..................................................................................................... xiii Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Literacy and critical Jewish thought ........................................................... 2 The sources of Jewish humor ..................................................................... 6 The Bible .............................................................................................. -

On Itzik Manger 'S “Khave Un Der Eplboym

לקט ייִ דישע שטודיעס הנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today לקט Der vorliegende Sammelband eröffnet eine neue Reihe wissenschaftli- cher Studien zur Jiddistik sowie philolo- gischer Editionen und Studienausgaben jiddischer Literatur. Jiddisch, Englisch und Deutsch stehen als Publikationsspra- chen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Leket erscheint anlässlich des xv. Sym posiums für Jiddische Studien in Deutschland, ein im Jahre 1998 von Erika Timm und Marion Aptroot als für das in Deutschland noch junge Fach Jiddistik und dessen interdisziplinären אָ רשונג אויסגאַבעס און ייִדיש אויסגאַבעס און אָ רשונג Umfeld ins Leben gerufenes Forum. Die im Band versammelten 32 Essays zur jiddischen Literatur-, Sprach- und Kul- turwissenschaft von Autoren aus Europa, den usa, Kanada und Israel vermitteln ein Bild von der Lebendigkeit und Viel- falt jiddistischer Forschung heute. Yiddish & Research Editions ISBN 978-3-943460-09-4 Jiddistik Jiddistik & Forschung Edition 9 783943 460094 ִיידיש ַאויסגאבעס און ָ ארשונג Jiddistik Edition & Forschung Yiddish Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 לקט ִיידישע שטודיעס ַהנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Yidish : oysgabes un forshung Jiddistik : Edition & Forschung Yiddish : Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 Leket : yidishe shtudyes haynt Leket : Jiddistik heute Leket : Yiddish Studies Today Bibliografijische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografijie ; detaillierte bibliografijische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urhe- berrechtlich geschützt. -

Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China

Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China ANNE BIRRELL Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880347 (PDF) 9780824880354 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1988, 1993 Anne Birrell All rights reserved To Hans H. Frankel, pioneer of yüeh-fu studies Acknowledgements I wish to thank The British Academy for their generous Fel- lowship which assisted my research on this book. I would also like to take this opportunity of thanking the University of Michigan for enabling me to commence my degree programme some years ago by awarding me a National Defense Foreign Language Fellowship. I am indebted to my former publisher, Mr. Rayner S. Unwin, now retired, for his helpful advice in pro- ducing the first edition. For this revised edition, I wish to thank sincerely my col- leagues whose useful corrections and comments have been in- corporated into my text. -

Addendum for Outlook & District Music Festival

ADDENDUM FOR OUTLOOK & DISTRICT MUSIC FESTIVAL 2020 PIANO CLASSES JAZZ 713 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 19 years and under (D) 712 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 18 years and under (D) 711 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 17 years and under (D) 710 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 16 years and under (D) 709 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 15 years and under (D) 708 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 14 years and under (D) 707 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 13 years and under (D) 706 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 12 years and under (D) 705 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 11 years and under (D) 704 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 10 years and under (D) 703 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 9 years and under (D) 702 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 8 years and under (D) 701 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 7 years and under (D) 700 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 6 years and under (D) 720 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 19 years and under (D) 719 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 18 years and under (D) 718 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 16 years and under (D) 717 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 14 years and under (D) 716 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 12 years and under (D) 715 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 10 years and under (D) 714 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 8 years and under (D) 726 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, Parent & Son/Daughter, 18 years and under (D) 725 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, Parent & Son/Daughter, 16 years and under (D) 724 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, Parent & Son/Daughter, 14 years and under (D) 723 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, Parent & Son/Daughter, 12 years and under (D) 722 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, Parent & Son/Daughter, 10 years and under (D) 734 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, Concert Group, 19 years and -

A Few Words About Yiddish Songs. from the Leaflet of Tamara

A FEW WORDS ABOUT YIDDISH SONGS When I tell people that I teach Yiddish, they frequently ask, “Are there students who want to study it seriously, and are there people who speak Yiddish?” I tell them “Yes.” Then they ask “But why did your students decide to learn Yiddish?” Well, there are different reasons. Many people discover Yiddish through Jewish songs; they hear something appealing and mysterious in a melody and they the hear the unknown words. These are not just people who have Yiddish in their family background, but there are French, German, Chinese and even Hindus among my students. The great Yiddish writer, Isaac Bashevis Singer, at the time he was presented with the Nobel Prize for Literature, said: “ Yiddish is a language for all of us; the language of frightened men who still believe.” He was also asked “Why do you write in Yiddish when it is a dying language?” His response “With our people, nothing ever dies.” For me, Yiddish songs have a special power, and for many people Jewish culture has its origins in music. Since my early childhood, Yiddish was connected with the song “Tum-Balalayke.” In time I discovered the rich language of Jewish authors: Isaac Singer, Sholem Aleichem, Itzik Manger, Abraham Sutzkever, et cetera. I was exposed to the wisdom of Jewish proverbs and jokes, the appeal of Hassidic tales, the pivotal moments in Jewish history, and the influence of Yiddish on Jewish culture. The word “Klezmer” or “Klazmer” from the Hebrew “klay-zamer” means “the instruments of music," and in Yiddish it means “musician”. -

Drag Performance and Femininity: Redefining Drag Culture Through Identity Performance of Transgender Women Drag Queens

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects Capstone Projects 2017 Drag Performance and Femininity: Redefining Drag Culture through Identity Performance of Transgender Women Drag Queens Cristy Dougherty Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dougherty, C. (2017). Drag Performance and Femininity: Redefining Drag Culture through Identity Performance of Transgender Women Drag Queens [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/730/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Drag Performance and Femininity: Redefining Drag Culture through Identity Performance of Transgender Women Drag Queens By Cristy A. Dougherty A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In Communication Studies Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota July 2017 Title: Drag Performance and Femininity: Redefining Drag Culture through Identity Performance of Transgender Women Drag Queens Cristy A.