Tongue-Twisted: Itzik Manger Between Mame-Loshn And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baal Shem-Toy Ballads of Shimshon Meltzer

THE BAAL SHEM-TOY BALLADS OF SHIMSHON MELTZER by SHLOMO YANIV The literary ballad, as a form of narrative metric composition in which lyric, epic, and dramatic elements are conjoined and whose dominant mood is one of mystery and dread, drew its inspiration from European popular ballads rooted in oral tradition. Most literary ballads are written in a concentrated and highly charged heroic and tragic vein. But there are also those which are patterned on the model of Eastern European popular ballads, and these poems have on the whole a lyrical epic character, in which the horrific motifs ordinarily associated with the genre are mitigated. The European literary ballad made its way into modern Hebrew poetry during its early phase of development, which took place on European soil; and the type of balladic poem most favored among Hebrew poets was the heroico-tragic ballad, whose form was most fully realized in Hebrew in the work of Shaul Tchernichowsky. With the appearance in 1885 of Abba Constantin Shapiro's David melek yifrii.:>e/ f:tay veqayyii.m ("David King of Israel Lives"), the literary ballad modeled on the style of popular ballads was introduced into Hebrew poetry. This type of poem was subsequently taken up by David Frischmann, Jacob Kahan, and David Shimoni, although the form had only marginal significance in the work of these poets (Yaniv, 1986). 1 Among modern Hebrew poets it is Shimshon Meltzer who stands out for having dedicated himself to composing poems in the style of popular balladic verse. These he devoted primarily to Hasidic themes in which the figure and personality of Israel Baal Shem-Tov, the founder of Hasidism, play a prominent part. -

The Image of Streetwalkers in Itzik Manger's and Debora Vogel's

The Image of Streetwalkers in Itzik Manger’s and Debora Vogel’s Ballads by Ekaterina Kuznetsova and Anastasiya Lyubas In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies (December 2020) For the online version of this article: http://ingeveb.org/articles/the-image-of-streetwalkers In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies (December 2020) THE IMAGE OF STREETWALKERS IN ITZIK MANGER’S AND DEBORA VOGEL’S BALLADS Ekaterina Kuznetsova and Anastasiya Lyubas Abstract: This article focuses on three ballads by Itzik Manger ( Di balade fun der zind, Di balade fun gasn-meydl, Di balade fun der zoyne un dem shlankn husar ) and two ballads by Debora Vogel ( Balade fun a gasn-meydl I un II ). We argue that Manger and Vogel subvert the ballad genre and gender hierarchies by depicting promiscuous female embodiment, theatricality, and the valuation of “lowbrow” culture of shund in their sophisticated poetic practices. These polyphonous texts integrate theatrical and folkloric song elements into “highbrow” Modernist aesthetics. Furthermore, these works by Manger and Vogel draw from both European influences and Jewish cultural traditions; they contend with urban modernity, as well as the resultant changes in the structures of Jewish life. By considering the image of the streetwalker in Manger’s and Vogel’s work, we deepen the understanding of Yiddish creativity as ultimately multimodal and interconnected. 1. Itzik Manger’s and Debora Vogel’s Ballads: Points of Contact Our study aims to bring two Yiddish authors—Itzik Manger and Debora Vogel—into dialogue. Manger and Vogel wrote numerous ballads where they integrated Eastern European folklore and interwar popular Jewish culture into this European literary genre. -

The Yiddishists

THE YIDDISHISTS OUR SERIES DELVES INTO THE TREASURES OF THE WORLD’S BIGGEST YIDDISH ARCHIVE AT YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH From top: Illustration from Kleyne Mentshelekh (Tiny Little People), a Yiddish adaptation of Gulliver’s Travels published in Poland, 1925. The caption reads, “With great effort I liberated my left hand.”; cover page for Kleyne Mentshelekh Manger was not the only 20th-century Yiddish-speaking Jew to take an interest in Swift’s 18th-century works. Between 1907 and 1939, there were at least five Yiddish translations and adaptations of Gulliver’s Travels published in the United States, Poland and Russia. One such edition, published in 1925 by Farlag Yudish, a publishing house that specialised in Yiddish translations of literary classics, appeared in their Kinder-bibliotek (Children’s Library) series alongside other beloved books such as Harriet Beecher GULLIVER IN YIDDISHLAND Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Edith Nesbit’s The Enchanted Castle and fairytales by the Jonathan Swift, Oscar Wilde and Samuel Beckett were just some brothers Grimm. Literature and journals THE YIDDISHISTS of the Anglo-Irish and Irish writers whose work was translated and for children and youth, both those written specifically in Yiddish and those translated adapted by 20th-century Yiddishists, says Stefanie Halpern into the language, were a lucrative branch of Yiddish publishing in the interwar n his 1942 poem ‘A Song of the Dean of Stella’s golden brooch, a reference to ‘A period. Such material became especially Jonathan Swift and the Yiddish Journal to Stella’, Swift’s 1766 work based important with the establishment of a IRhyme-maker Itzik Manger’, the poet on letters he sent to his real-life lover Yiddish secular school network across and playwright Itzik Manger imagines a Esther Johnson. -

Jewish Humor

Jewish Humor Jewish Humor: An Outcome of Historical Experience, Survival and Wisdom By Arie Sover Jewish Humor: An Outcome of Historical Experience, Survival and Wisdom By Arie Sover This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Arie Sover All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6447-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6447-3 With love to my parents, Clara (Zipkis) and Aurel Sober, and my grandmother, Fanny Zipkis: Holocaust survivors who bequeathed their offspring with a passion for life and lots of humor. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. xii Preface ..................................................................................................... xiii Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Literacy and critical Jewish thought ........................................................... 2 The sources of Jewish humor ..................................................................... 6 The Bible .............................................................................................. -

On Itzik Manger 'S “Khave Un Der Eplboym

לקט ייִ דישע שטודיעס הנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today לקט Der vorliegende Sammelband eröffnet eine neue Reihe wissenschaftli- cher Studien zur Jiddistik sowie philolo- gischer Editionen und Studienausgaben jiddischer Literatur. Jiddisch, Englisch und Deutsch stehen als Publikationsspra- chen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Leket erscheint anlässlich des xv. Sym posiums für Jiddische Studien in Deutschland, ein im Jahre 1998 von Erika Timm und Marion Aptroot als für das in Deutschland noch junge Fach Jiddistik und dessen interdisziplinären אָ רשונג אויסגאַבעס און ייִדיש אויסגאַבעס און אָ רשונג Umfeld ins Leben gerufenes Forum. Die im Band versammelten 32 Essays zur jiddischen Literatur-, Sprach- und Kul- turwissenschaft von Autoren aus Europa, den usa, Kanada und Israel vermitteln ein Bild von der Lebendigkeit und Viel- falt jiddistischer Forschung heute. Yiddish & Research Editions ISBN 978-3-943460-09-4 Jiddistik Jiddistik & Forschung Edition 9 783943 460094 ִיידיש ַאויסגאבעס און ָ ארשונג Jiddistik Edition & Forschung Yiddish Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 לקט ִיידישע שטודיעס ַהנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Yidish : oysgabes un forshung Jiddistik : Edition & Forschung Yiddish : Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 Leket : yidishe shtudyes haynt Leket : Jiddistik heute Leket : Yiddish Studies Today Bibliografijische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografijie ; detaillierte bibliografijische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urhe- berrechtlich geschützt. -

A Few Words About Yiddish Songs. from the Leaflet of Tamara

A FEW WORDS ABOUT YIDDISH SONGS When I tell people that I teach Yiddish, they frequently ask, “Are there students who want to study it seriously, and are there people who speak Yiddish?” I tell them “Yes.” Then they ask “But why did your students decide to learn Yiddish?” Well, there are different reasons. Many people discover Yiddish through Jewish songs; they hear something appealing and mysterious in a melody and they the hear the unknown words. These are not just people who have Yiddish in their family background, but there are French, German, Chinese and even Hindus among my students. The great Yiddish writer, Isaac Bashevis Singer, at the time he was presented with the Nobel Prize for Literature, said: “ Yiddish is a language for all of us; the language of frightened men who still believe.” He was also asked “Why do you write in Yiddish when it is a dying language?” His response “With our people, nothing ever dies.” For me, Yiddish songs have a special power, and for many people Jewish culture has its origins in music. Since my early childhood, Yiddish was connected with the song “Tum-Balalayke.” In time I discovered the rich language of Jewish authors: Isaac Singer, Sholem Aleichem, Itzik Manger, Abraham Sutzkever, et cetera. I was exposed to the wisdom of Jewish proverbs and jokes, the appeal of Hassidic tales, the pivotal moments in Jewish history, and the influence of Yiddish on Jewish culture. The word “Klezmer” or “Klazmer” from the Hebrew “klay-zamer” means “the instruments of music," and in Yiddish it means “musician”. -

New Chapter for the 27Th Annual Jewish

Washtenaw Jewish News Presort Standard In this issue… c/o Jewish Federation of Greater Ann Arbor U.S. Postage PAID 2939 Birch Hollow Drive Ann Arbor, MI Ann Arbor, MI 48108 Permit No. 85 2014 Apples & Year in Maccabi Honey Review Games Photo Album Page 14 Page 17 Page 18 October 2014 Tishrei/Cheshvan 5775 Volume XXXIX Number 2 FREE New chapter for the 27th Annual Jewish Book Festival Clara Silver, special to the WJN he 27th Annual Jewish Book Festi- book Writing in Tongues: women/trailblazing, sports, humor, politics, val promises to be one of the most Translating Yiddish in history, biography, music, entertainment, Is- T enriching and memorable cultural the 20th Cen- rael, the Holocaust, and more. Featured visit- events of the year hosted by the Jewish Com- tury, by Tikva ing authors will include Gail Sheehy, Oliver munity Center of Greater Ann Arbor and Frymer-Kensky Horovitz, Zieva Konvisser, Ayelet Waldman, co-hosted this year by the Ann Arbor District Collegiate Pro- Yochi Dreazen, Liel Leibowitz, Barbara Win- Library. The Festival will run from Wednes- fessor Dr. Anita ton, James Grymes, Dori Weinstein, P’ninah day, November 5, to Sunday, November 16. Norich. Opening and Karl Kanai, Dina Shtull, and Annabelle In addition to the variety of visiting authors night, Saturday, Gurwitch. and the in-house book and gift store, the November 8, will Special events this year will include mu- Book Festival will host lunch events, music, include a dinner sic nights on Wednesday, November 12, at 7 and film events. The Book Festival will be- for Book Festi- p.m., featuring A Broken Hallelujah, by Liel gin with two preview events showcasing both val sponsors at 6 Leibowitz chronicling the life of musician visiting and local scholars from the Universi- p.m. -

Why I Write in Yiddish

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 22 (2020) Issue 1 Article 12 Why I Write in Yiddish Karen Alkalay-Gut Tel Aviv University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), -

New Yiddish Library YD7250

YD7250. i-xlvi 4/8/02 8:18 AM Page i New Yiddish Library YD7250. i-xlvi 4/8/02 8:18 AM Page ii The New Yiddish Library is a joint project of the Fund for the Translation of Jewish Literature and the National Yiddish Book Center Additional support comes from the Kaplen Foundation and the Felix Posen Fund for the Translation of Modern Yiddish Literature series editor: david g. roskies YD7250. i-xlvi 4/8/02 8:18 AM Page iii The World According to Itzik: Selected itzik manger Poetry translated and edited by leonard wolf and with an introduction by david g. roskies and Prose leonard wolf yale university press new haven & london YD7250. i-xlvi 4/8/02 8:18 AM Page iv Copyright © 2002 by the Fund for the Translation of Jewish Literature. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in- cluding illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sec- tions 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. “The Ballad and the White Glow,” “The Crucified and the Verminous Man,” “For Years I Wallowed,” “Hagar Leaves Abraham’s House,” “In the Train,” “Jacob Teaches the Story of Joseph to His Sons,” “November,” “The Patri- arch Jacob Meets Rachel,” all by Itzik Manger, translated by Leonard Wolf, from The Penguin Book of Modern Yiddish Verse, by Irving Howe, Ruth R. Wisse, and Khone Shmeruk, copyright © 1987 by Irving Howe, Ruth Wisse, and Chone Shmeruk. -

“Thrillingly Alive... Skillfully Delivered” -NY POST (Critic’S Pick)

“thrillingly alive... skillfully delivered” -NY POST (Critic’s Pick) BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND MARCH 2 - 16, 2014 The 2014 production of THE MEGILE OF ITZIK MANGER plans to: ENGAGE Over 3,600 people attended the 2013 three-week engagement of THE MEGILE OF ITZIK MANGER. The production exceeded expectations of reaching a diverse audience. With your support, the upcoming production will be more accessible with a scaled ticket pricing system engaging an even wider net of exposure, especially for individuals under 30. EDUCATE THE MEGILE OF ITZIK MANGER prepares the next generation of audiences through the spectacle of circus as a means to provide insight into history, culture, and tradition - closing the gap that exists between education and entertainment. PARTNER THE MEGILE OF ITZIK MANGER will partner with schools and community groups to hold stimulating post-show discussions, in-school visits from teaching artists, and provide study guides. BRIDGE As a critically-acclaimed vehicle, THE MEGILE OF ITZIK MANGER proves the continued relevance of Yiddish Theatre in today’s world, bridging the language barrier through unconventional expressive storytelling and the use of English and Russian supertitles. PRESS QUOTES “a home run...[that] keeps the ear and eye delighted throughout.” “ thrillingly alive...skillfully delivered” -Miriam Rinn, THE JEWISH STANDARD -Frank Scheck, NY POST (Critic’s Pick) “a clever production with a lot of heart” “boasts a freshness and vitality” -Marti Sichel, WOMAN AROUND TOWN -Raven Snook, TIME OUT NY (Critic’s Pick) “If MEGILE doesn’t sweep you off your feet, “a fun show that I recommend” chances are, nothing will.” -Ed Malin, NYTHEATRE.COM (Critic’s Choice) -Ted Merwin, THE JEWISH WEEK “outstanding...[a] cause for celebration!“ “Zalmen Mlotek’s band gets the sound just right, -Paulanne Simmons, CURTAIN UP and Dov Seltzer’s music is superb, sung by a wondrous cast.” -Peter Filichia, FILICHIA ON FRIDAYS “This production had me splitting my sides with laughter, crying, and captivated.” “outstandingly directed...choreographed with zest.. -

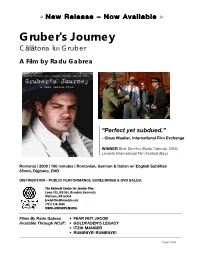

Gruber's Journey Press

☆ New Release – Now Available ☆ Gruber's Journey Călătoria lui Gruber A Film by Radu Gabrea “Perfect yet subdued.” - Claus Mueller, International Film Exchange WINNER Best Director (Radu Gabrea), 2009 Levante International Film Festival (Italy) Romania | 2008 | 100 minutes | Romanian, German & Italian w/ English Subtitles 35mm, Digibeta, DVD DISTRIBUTION - PUBLIC PERFORMANCE SCREENINGS & DVD SALES: The National Center for Jewish Film Lown 102, MS 053, Brandeis University Waltham, MA 02454 [email protected] (781) 736-8600 WWW.JEWISHFILM.ORG Films By Radu Gabrea • FEAR NOT JACOB Available Through NCJF: • GOLDFADEN’S LEGACY • ITZIK MANGER • RUMENYE! RUMENYE! Page 1 of 4 Gruber's Journey A Film by Radu Gabrea Romania | 2008 | 100 minutes | Fiction Feature Film Romanian, German & Italian w/ English Subtitles 35mm; Digibeta; DVD Festivals & Broadcast FESTIVAL SCREENINGS • San Francisco Jewish Film Festival 2010 (upcoming) • Caracas (Venezuela) Jewish Film Festival 2010 (upcoming) • New York Jewish Film Festival, Lincoln Center 2010 • Levante International Film Festival (Italy) 2009 • Vancouver Jewish Film Festival 2009 • Philadelphia Jewish Film Festival 2009 • Contra Costa International Jewish Film Festival 2009 • Silicon Valley Jewish Film Festival 2009 • European Union Film Festival, Chicago 2009 • Atlanta Jewish Film Festival 2009 • Toronto Jewish Film Festival 2009 • Romanian Film Festival, New York 2008 • Klezmer Festival Buenos Aires, Argentina 2008 • Jerusalem Film Festival 2008 • Transylvania International Film Festival 2008 Synopsis In June 1941, Curzio Malaparte (Florin Piersic Jr.), an Italian journalist and member of the Fascist party, arrives in the Romanian city of Iasi on the way to cover the Russian front for an Italian newspaper. Suffering from severe allergies, he is referred to Josef Gruber (Marcel Iureş), a local Jewish doctor. -

Tanakh and Textuality in Early Modern Yiddish Literature

Exegetical Poetics: Tanakh and Textuality in Early Modern Yiddish Literature By Rachel Alexandra Wamsley A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Robert Alter Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Simon Neuberg Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2015 Exegetical Poetics: Tanakh and Textuality in Early Modern Yiddish Literature © 2015 by Rachel Alexandra Wamsley Abstract Exegetical Poetics: Tanakh and Textuality in Early Modern Yiddish Literature by Rachel Alexandra Wamsley Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair This dissertation examines Yiddish literature (1500-1950) as an alternative, even transgressive, vehicle for the transmission of the Hebrew Bible and classical rabbinic interpretation. In biblical works for popular audiences—which included women, children, and even non-Jews—Yiddish enjoyed a relative freedom from literary and doctrinal regulation. Through this freedom to improvise on the biblical canon, I argue, early Yiddish literature discloses hermeneutic and poetic practices inadmissible in contemporary Hebrew literature: humanist textual criticism, ambiguous or subversive midrash, the vivid portrayal of non-Jewish subjectivities. By reading this cultural palimpsest as a single multilingual and transnational history, I access those unsanctioned and clandestine practices in Jewish biblical transmission suppressed in the Hebrew sources. At the same time, the material evidence offered by my work with early Yiddish and Hebrew books sheds light on the entanglement of religious authority and textual transmission. Recent scholarly attention has focused on the social history of the printing house (in contrast to the printing press) as the site of an evolving textual culture in the early modern period.