Criminal Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 11 February 2015 6007 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11 February 2015 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. 6008 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 11 February 2015 THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONNY TONG KA-WAH, S.C. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. -

Work.Of The: I ! '.'

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. a 4 .~ ~ '0 \l l.'J '" ,., ,I l" J ~ I· I I ~ !1 ~ -" 0 ' I u i ! :- ..... ~- i .">,',,> • ,.;;- '~?'/ .. ' ...••.. ' ,.: '~SUMMARY '. OFrJil,!E 1., " ";':,' :( WORK.OF THE: I ! '.' 1982.'- .... 91578 Thli document hal been ~I.!ced exactly as r~vlld from tile peraon 01' Ul'gllnlzallon originating II. PoInll of view or Opinions stated 11\ IhII document are thoM of the .u\hOB and do not necessarily rtIPf-' :Nt oIiicI4!l poeiIIon 01' poIIc:iea of til_ ~.~ Institute of .Mti~; Permiuion to repradUce this copyright«l material has Imn o~edby" ' Jiorlg Kong Correctional Services ne:part:m.mt ' to the NatIonal Criminal Justice Referlln(» S0rvice (NCJRS). a Furth« reproduction outIIkIe d fie Nc.J!lS 5)'Stem requires permis t lion of lfIe cop~1 owner. l' LO o " Q r 9lS1Y CON TEN T 5 .~ i j~:1fj t {. ...." Chapter !f NC3R5 Paragraphs 1I~ «leT lO '~R~ 1. GENERAL REVIEW t - 14 Awards and comme+at~U1S"TIONS 15 18 Refugees and Per~ons Detained under the ImmigratioJ Ordinance 19 - 26 Census of Vietnamese Refugee Detained in Closed Centres 27 Census of P.enal Population 28 United~Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners 29 Psychological Services and Programme Deve lopment 30 Escort Unit 31 Co-operation - Law and Order 32 33 Works Unit 34 - 37 II. MALE OFFENDERS - PRISONS Adults 38 - 42 Education 43 - 48 , Physical Education and Recreation 49 51 . Work and Vocational Training 52 55 Oiscipline 56 Geriatric Prisoners 57 - 59 Handicapped Prisoners 60 Young Men 6·1 - 64 Discipline 65· The Hong Kong Discharge~ Prisoners ~id Society . -

Final Program of CCC2020

第三十九届中国控制会议 The 39th Chinese Control Conference 程序册 Final Program 主办单位 中国自动化学会控制理论专业委员会 中国自动化学会 中国系统工程学会 承办单位 东北大学 CCC2020 Sponsoring Organizations Technical Committee on Control Theory, Chinese Association of Automation Chinese Association of Automation Systems Engineering Society of China Northeastern University, China 2020 年 7 月 27-29 日,中国·沈阳 July 27-29, 2020, Shenyang, China Proceedings of CCC2020 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP2040A -USB ISBN: 978-988-15639-9-6 CCC2020 Copyright and Reprint Permission: This material is permitted for personal use. For any other copying, reprint, republication or redistribution permission, please contact TCCT Secretariat, No. 55 Zhongguancun East Road, Beijing 100190, P. R. China. All rights reserved. Copyright@2020 by TCCT. 目录 (Contents) 目录 (Contents) ................................................................................................................................................... i 欢迎辞 (Welcome Address) ................................................................................................................................1 组织机构 (Conference Committees) ...................................................................................................................4 重要信息 (Important Information) ....................................................................................................................11 口头报告与张贴报告要求 (Instruction for Oral and Poster Presentations) .....................................................12 大会报告 (Plenary Lectures).............................................................................................................................14 -

Summary of the Work of the Prisons Department by the Commissioner of Prisons T.G. Garner, C.B.E., J.P. for the Year

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I • A SUMMARY OF THE WORK OF THE PRISONS DEPARTMENT BY THE COMMISSIONER OF PRISONS T.G. GARNER, C.B.E., J.P. FOR THE YEAR 1981 -----...---: ,.. CONTENTS Chapter m82 iWV 2~ Paragraphs I. GENERAL REVIEW ............................... 1 11 d d . ACQUESrrrrON' Awar san Commen d atzons ................... ¥ •• 12 - 15 Refugees and Persons Detained under the Immigration Ordinance . ................................. 16 18 Census of Penal Population ....................... 19 20 Psychological Services . 21 Recidivism · ................... , .............. 22 Escort Unit · ................................... 23 24 Co-operation - Law & Order .................... 25 26 Discipline - Penal Institutions ................... 27 28 Works Unit .... .' .............................. 29 32 II. MALE OFFENDERS - PRISONS Adults . ...................................... 33 37 Education . ................................. 38 40 Physical Education and Recreation ............... 41 43 Work & Vocational Training . ................... U.S. Department of Justice 86417 44 47 National Institute of Justice Discipline .................................. 48 This document has been reproduced exactly as recei~e~ from the Geriatric Prisoners ........................... person or organization originating it. Points of view or opInions stat~d 49 - 51 in this document are those of the authors and do. not nec~ssarlly Handicapped Prisoners ........................ represent the official position or policies -

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T. Tsang Tai Uk (曾大屋, literally the Big Mansion of the Tsang Family) is also Historical called Shan Ha Wai (山廈圍, literally, Walled Village at the Foothill). Its Interest construction was started in 1847 and completed in 1867. Measuring 45 metres by 137 metres, it was built by Tsang Koon-man (曾貫萬, 1808-1894), nicknamed Tsang Sam-li (曾三利), who was a Hakka (客家) originated from Wuhua (五華) of Guangdong (廣東) province which was famous for producing masons. He came to Hong Kong from Wuhua working as a quarryman at the age of 16 in Cha Kwo Ling (茶果嶺) and Shaukiwan (筲箕灣). He set up his quarry business in Shaukiwan having his shop called Sam Lee Quarry (三利石行). Due to the large demand for building stone when Hong Kong was developed as a city since it became a ceded territory of Britain in 1841, he made huge profit. He bought land in Sha Tin from the Tsangs and built the village. The completed village accommodated around 100 residential units for his family and descendents. It was a shelter of some 500 refugees during the Second World War and the name of Tsang Tai Uk has since been adopted. The sizable and huge fortified village is a typical Hakka three-hall-four-row Architectural (三堂四横) walled village. It is in a Qing (清) vernacular design having a Merit symmetrical layout with the main entrance, entrance hall, middle hall and main hall at the central axis. Two other entrances are to either side of the front wall. -

CRIME, JUSTICE and PUNISHMENT in COLONIAL HONG KONG Central Police Station, Central Magistracy and Victoria Gaol

CRIME, JUSTICE AND PUNISHMENT IN COLONIAL HONG KONG Central Police Station, Central Magistracy and Victoria Gaol May Holdsworth & Christopher Munn iii Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong https://hkupress.hku.hk © 2020 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8528-12-7 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Picture Researcher: David Bellis Research Assistants: Danny Chung Chi Kit, Peter E. Hamilton, Hannah Keen Design: New Strategy Ltd 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Hang Tai Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 PART ONE CENTRAL POLICE STATION 17 1 Barrack Block and Headquarters Block 19 2 A Colonial Police Force 35 3 Turning Points 67 PART TWO CENTRAL MAGISTRACY 95 4 Building the Magistracy, 1847–1914 97 5 Magistrates, Society and the Law in Colonial Hong Kong 109 6 One Million Cases: Glimpses of the Magistracy, 1841–1941 147 PART THREE VICTORIA GAOL 179 7 A Relic of Victorian Prison Design 181 8 ‘The Question of Insufficient Accommodation’ 207 9 ‘Hope Dies!’ — Entering the Gaol 232 10 Punishment, Resistance and Release 263 A Timeline of Key Events 295 Appendix 302 Select Bibliography 305 Illustration Credits 308 Notes 310 Index 323 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION Standing close together on a hillside above Hong Kong harbour, the Central Police Station, Central Magistracy and Victoria Gaol occupy a whole block in Hollywood Road, at the very centre of the city. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 19

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 19 December 2007 2969 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 19 December 2007 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, G.B.S., J.P. 2970 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 19 December 2007 THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE YEUNG SUM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. -

Economic Reform Through Political Leadership in China’S State-Owned Economy

ECONOMIC REFORM THROUGH POLITICAL LEADERSHIP IN CHINA’S STATE-OWNED ECONOMY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Wendy Elizabeth Leutert August 2017 © 2017 Wendy Elizabeth Leutert ECONOMIC REFORM THROUGH POLITICAL LEADERSHIP IN CHINA’S STATE-OWNED ECONOMY Wendy Elizabeth Leutert, Ph.D. Cornell University 2017 This dissertation examines the impact of political leadership on economic reform in China’s state-owned economy. I argue that the heads of public sector organizations, at the central level and below, shape reform policy experimentation and implementation through their choices concerning organizational strategy and structure. Following a review of the key state-owned enterprise reform policies in China since 1978, I utilize case study analysis to assess the effects of political leadership exercised by consecutive chairmen of a central state-owned enterprise on the firm’s reform. As the government-directed restructuring of state-owned assets remains an important component of economic reform in China, I next use logistic regression models to analyze the effects of political leadership on mergers among central state-owned enterprises between 2003 and 2015. Finally, I identify four mechanisms that link the organizational change fashioned by political leadership with broader evolution in the institution of state ownership. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Wendy Leutert is from Bradford, Pennsylvania and Naples, Florida. She attended Wellesley College, graduating summa cum laude with honors in both political science and philosophy. After studying Mandarin at Cornell University’s Full-year Asian Language Concentration (FALCON) Program and at U.C. -

World Factbook of Criminal Justice Systems

WORLD FACTBOOK OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMS Hong Kong Ian Dobinson City Polytechnic of Hong Kong This country report is one of many prepared for the World Factbook of Criminal Justice Systems under Bureau of Justice Statistics grant no. 90- BJ-CX-0002 to the State University of New York at Albany. The project director was Graeme R. Newman, but responsibility for the accuracy of the information contained in each report is that of the individual author. The contents of these reports do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Bureau of Justice Statistics or the U.S. Department of Justice. GENERAL OVERVIEW i. Political System. The criminal justice system of Hong Kong suffers from over bureaucratization and a lack of coordination. In general, Departments and agencies are administered by the executive, with the Governor as its head. Under $4 of the Police Force Ordinance (Cap 232), for example, the Commissioner is directly accountable to the Governor. For the other main agencies, direct administrative responsibility lies with other senior members of the executive. The decision to prosecute is determined by the Attorney General while corrections are administered by the Departments of Correctional Services and Social Welfare, which are the responsibility of the Secretaries of Security and Social Welfare, respectively. The judiciary has apparent independence. However, the powers of the Governor to appoint both judges and magistrates, as delegated by the Queen, may be seen as hampering true independence. 2. Legal System. While there are important differences, the structure of the government and criminal justice system of Hong Kong is the same as other British colonies. -

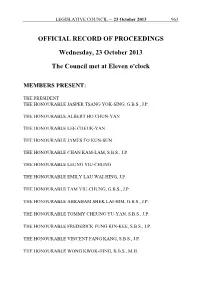

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 23 October 2013 963 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 23 October 2013 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. 964 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 23 October 2013 PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONNY TONG KA-WAH, S.C. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEUNG KA-LAU THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG KWOK-CHE THE HONOURABLE IP KWOK-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. -

The Internment of Western Civilians Under the Japanese 1941-1945

THE INTERNMENT OF WESTERN CIVILIANS UNDER THE JAPANESE 1941–1945 RoutledgeCurzon Studies in the Modern History of Asia 1 The Police in Occupation Japan Control, corruption and resistance to reform Christopher Aldous 2 Chinese Workers A new history Jackie Sheehan 3 The Aftermath of Partition in South Asia Tai Yong Tan and Gyanesh Kudaisya 4 The Australia-Japan Political Alignment 1952 to the present Alan Rix 5 Japan and Singapore in the World Economy Japan’s Economic Advance into Singapore, 1870–1965 Shimizu Hiroshi and Hirakawa Hitoshi 6 The Triads as Business Yiu Kong Chu 7 Contemporary Taiwanese Cultural Nationalism A-chin Hsiau 8 Religion and Nationalism in India The Case of the Punjab Harnik Deol 9 Japanese Industrialisation Historical and Cultural Perspectives Ian Inkster 10 War and Nationalism in China 1925–1945 Hans J. van de Ven 11 Hong Kong in Transition One Country, Two Systems Edited by Robert Ash, Peter Ferdinand, Brian Hook and Robin Porter 12 Japan’s Postwar Economic Recovery and Anglo-Japanese Relations, 1948–1962 Noriko Yokoi 13 Japanese Army Stragglers and Memories of the War in Japan, 1950–1975 Beatrice Trefalt 14 Ending the Vietnam War The Vietnamese Communists’ Perspective Ang Cheng Guan 15 The Development of the Japanese Nursing Profession Adopting and Adapting Western Influences Aya Takahashi 16 Women’s Suffrage in Asia Gender Nationalism and Democracy Louise Edwards and Mina Roces 17 The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902–1922 Phillips Payson O’Brien 18 The United States and Cambodia, 1870–1969 From Curiosity to Confrontation Kenton Clymer 19 Capitalist Restructuring and the Pacific Rim Ravi Arvind Palat 20 The United States and Cambodia, 1969–2000 A Troubled Relationship Kenton Clymer 21 British Business in Post-Colonial Malaysia, 1957–70 ‘Neo-colonialism’ or ‘Disengagement’ Nicholas J. -

Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/ASIA HONG KONG HUMAN RIGHTS MONITOR June 1997 Vol. 9, No. 5 (C) HONG KONG PRISON CONDITIONS IN 1997 PREFACE............................................................................................................................................................................... 2 I. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS..................................................................................................................... 6 II. AN OVERVIEW OF THE PRISON SYSTEM ................................................................................................................ 9 III. PHYSICAL CIRCUMSTANCES .................................................................................................................................. 15 IV. AGOOD ORDER,@ DISCIPLINE, AND PUNISHMENT.............................................................................................. 22 V. CONTACTS WITH THE OUTSIDE.............................................................................................................................. 30 VI. WORK AND OTHER ACTIVITIES............................................................................................................................. 37 VII. SPECIAL CATEGORIES OF PRISONERS................................................................................................................ 39 VIII. MONITORING OF TREATMENT AND CONDITIONS ......................................................................................... 44 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................................................