Council of Europe Conseil De L'europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ordesa: Del Valle Perdido Al Símbolo Patrimonial 1

EDUARDO MARTÍNEZ DE PISÓN Departamento de Geografía. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Ordesa: del valle perdido al símbolo patrimonial 1 RESUMEN qui a cherché son sens patrimonial tout au long de la première moitié A partir de los relatos de los pirineístas, el valle de Ordesa adquirió du siècle XX. renombre por su apartamiento y calidades naturales. Las amenazas a sus paisajes dieron lugar a una campaña para su protección que coin- ABSTRACT cidió con la creación de los parques nacionales en España (1916). Se Ordesa : from last valley to heritage emblem.- From the accounts of formó allí un espacio protegido de tamaño restringido pero de fama the Pyreneans writers, Ordesa Valley acquired renown by his apartment internacional que buscó su sentido patrimonial a lo largo de la primera and natural qualities. The threats to its landscapes gave place to a cam- mitad del siglo XX. paign for its protection that coincided with the creation of national parks in Spain (1916). There was formed a protected space of restricted RÉSUMÉ size but of international fame that has looked for its heritage meaning Ordesa: de la vallée perdue au symbole patrimonial.- À partir des na- along the first half of the 20th century. rrations des pyrénéistes, la vallée d’Ordesa a acquis de la réputation par son éloignement et ses qualités naturelles. Les menaces à leurs paysa- PALABRAS CLAVE/MOTS CLÉ/KEYWORDS ges ont donné lieu à une campagne pour leur protection qui a coïncidé Ordesa, parque nacional, valor patrimonial. avec la création des parcs nationaux en Espagne (1916). On a formé là Ordesa, parc national, valeur patrimonial. -

Discover Sobrarbe 2017.Indd 1 20/07/2017 15:14:33 Introduction

Discover Sobrarbe _2017.indd 1 20/07/2017 15:14:33 Introduction The central Pyrenees, the mountain range spanning from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, is the steepest, wildest and most spectacular part of this land mass. Its highest peaks, its deepest valleys and its glaciers, together with a great variety of habitats hardly altered by human activity, have become the refuge of a great number of animal and plant species. Sobrarbe, one of the boroughs of the province of Huesca, spreads over 2,202 square kilometres in the Central Pyrenees and pre-Pyrenean ranges and includes the River Ara basin and the River Cinca headwaters and its tributaries. Cave paintings, dolmens and other findings show us that this land was populated in the Neolithic age. The Romans arrived many centuries later, then the Visigoths and later still the Moslems, who were expelled in the 10th century. There were hard times for the people of Sobrarbe although in the 16th century there was a period of prosperity. The 20th century brought about great improvements (investments, road networks) and great disasters (Civil War, eservoirs, depopulation…). Around 7,500 people live in Sobrarbe, most of whom work either inagriculture or in the service sector. They live in a privileged area ofgreat beauty. Sobrarbe aims at sustainable development according to the parameters of the Local Agenda 21. This guide is an invitation to walk through this area and learn about its history, its villages, its landscape and its people. Just a few clues will lead you to enjoy many of Sobrarbe’s beauty spots. -

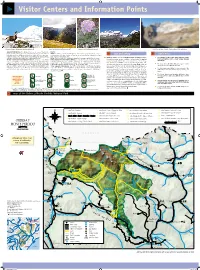

Visitor Centers and Information Points

Visitor Centers and Information Points Pyrenean chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra pyrenaica) Sunset in the Ordesa Valley in early fall Pyrenean violet (Ramonda myconi) Head of the Añisclo Canyon in early spring North face of Monte Perdido. Marboré glacial lake and glacier General Information. The National Park can be reached through the Routes towns of Torla (Ordesa), Escalona and Fanlo (Añisclo), Escuaín and Tel- Trails.The Park has a network of hiking trails. These trails are properly marked, except in tips and safety don’t miss la-Revilla (Escuaín), and Bielsa (Pineta). The National Park is open year- certain sections at higher elevations. There are forest trails that are restricted from use round and entry is free. A wide range of accommodation options (hotels, both in and surrounding the Park. Warning: caution! You are in a high-mountain landscape. At times, The grandeur of the Ordesa Valley, naturally carved cottages, campsites, and hostels) are located near the Park. Hikes. Please contact local specialized companies to arrange a guided hike or ascent. this stunning region can pose a number of different risks. The weather from sedimentary rock to create unique contours Visitor Centers and Information Points. The Park has a main Visitor Public transport to the Ordesa Valley. Access to the Ordesa Valley in private vehicle and shapes. Center in the village of Torla and a sensorium for the physically handi- is prohibited during the summer months and Easter week. A public bus service will provide in mountain ranges like the Pyrenees is unpredictable and can change capped, “Casa Oliván”, located in the Ordesa Valley a kilometer before the transportation to the Park during these times. -

Aragon 20000 of Trails

ENGLISH ARAGON 20,000 KM OF TRAILS BEAUTY AND ADVENTURE COME TOGETHER IN ARAGON’S EXTENSIVE NETWORK OF TRAILS. FROM THE HEIGHTS OF THE PYRENEES TO THE BREATHTAKING STEPPES OF THE EBRO AND THE MOST RUGGED MOUNTAIN RANGES ON THE IBERIAN PENINSULA, HERE YOU WILL FIND NATURE AT ITS BEST. HIKING TRAILS OF ARAGON LONG-DISTANCE PATHS THEMED LONG-DISTANCE HIKES WALKS AND EXCURSIONS CLIMBS ACCESIBLE TRAILS Download the app for the Hiking Trails of Aragon and go to senderosturisticos.turismodearagon.com / HIKING TRAILS OF ARAGON 01/ HIKING TRAILS OF ARAGON .................................. 1 02/ INDEX OF TRAILS IN THIS GUIDE .................... 4 03/ LONG-DISTANCE PATHS ........................................ 6 04/ THEMED LONG-DISTANCE HIKES ............... 9 05/ WALKS AND EXCURSIONS ............................... 12 06/ CLIMBS .................................................................................... 28 07/ ACCESSIBLE TRAILS ................................................ 32 Published by: PRAMES Photography: F. Ajona, D. Arambillet, A. Bascón «Sevi», Comarca Gúdar-Javalambre, Comarca Somontano de Barbastro, M. Escartín, R. Fernández, M. Ferrer, D. Mallén, Montaña Segura, M. Moreno, Osole Visual, Polo Monzón, Prames, D. Saz, Turismo de Aragón HIKING IS ONE OF THE BEST WAYS TO GET FIRSTHAND EXPERIENCE OF ALL THE NATURAL AREAS THAT ARAGON HAS TO OFFER, FROM THE SOUTHERNMOST GLACIERS IN EUROPE, FOUND ON THE HIGHEST PEAKS OF THE PYRENEES, TO THE ARID STEPPES OF THE EBRO VALLEY AND THE FASCINATING MOUNTAIN RANGES OF TERUEL. / HIKING TRAILS OF ARAGON In terms of landscapes and natural beauty, Aragon is exceptional. It is famous for the highest peaks in the Pyrenees, with Pico de Aneto as the loftiest peak; the Pre-Pyrenean mountain ranges, with Guara and the Mallos de Riglos as popular destinations for adventure sports worldwide; and the Iberian System, with Mount Moncayo as its highest peak and some of the most breathtakingly rugged terrain in Teruel. -

Hiking in the Spanish Pyrenees

HIKING IN THE SPANISH PYRENEES Ordesa National Park, Benasque and Romanesque Boi Valley CICMA: 2608 +34 629 379 894 www.exploring-spain.com [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Destination ............................................................................................................................................ 2 3 Basic information .................................................................................................................................. 2 3.1 Required physical condition and type of terrain ........................................................................... 2 4 Program ................................................................................................................................................. 3 4.1 Program outline ............................................................................................................................. 3 4.2 Detailed program .......................................................................................................................... 3 5 More information .................................................................................................................................. 5 5.1 Included ......................................................................................................................................... 5 5.2 Not included ................................................................................................................................. -

Pyreneesmonte Perdido Cultural Organization Heritage List in 1997 UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE NATURAL LANDSCAPE | CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

NIO M O UN IM D R T IA A L • P • W L O A I R D L D N H O E M R I E TA IN G O E • PATRIM United Nations Pyrénées - Mont Perdu Educational, Scientific and inscribed on the World PyreneesMonte Perdido Cultural Organization Heritage List in 1997 UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE NATURAL LANDSCAPE | CULTURAL LANDSCAPE 1 PirineosMonte Perdido UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE NIO M O UN IM D R T IA A L • P • W L O A I R D L D N H O E M R I E TA IN G O E • PATRIM United Nations Pyrénées - Mont Perdu Educational, Scientific and inscribed on the World Cultural Organization Heritage List in 1997 NATURAL LANDSCAPE | CULTURAL LANDSCAPE The Ordesa Valley | The Añisclo Canyon | The Escuaín Gorges | The Pineta Valley | The Gavarnie cirque | The Estaubé cirque | The Troumouse cirque | The Barroude cirque www.pirineosmonteperdido.com 2 A few words about World Heritage spectacular geo-diversity and key places ¿What does it mean to be en- to fully understand the Pyrenees’ for- listed as a World Heritage site? mation, making it worthy of World Her- itage status, the site is centred around World Heritage is a designation award- the summit of Monte Perdido at 3348 ed to locations or properties, situated Mts, and covering an area of 30639 Hect- anywhere in the world, which hold ex- ares, it boasts exceptional landscapes of ceptional universal value. As such, they meadows, lakes, caves and forests over are registered under the protection of its alpine slopes. the World Heritage List so that future generations can continue to enjoy them. -

Aragon / Is Nature

ENGLISH ARAGON / IS NATURE IF YOU LOVE UNSPOILT NATURE AND PRISTINE OPEN SPACES, IN ARAGON YOU WILL FIND WHAT YOU ARE LOOKING FOR. SECLUDED AND ENCHANTING PLACES THAT WILL AWAKEN YOUR IMAGINATION. THE ORDESA VALLEY IS ONE OF THE MOST BEAUTIFUL PLACES IN SPAIN AND A UNIQUE HIGH MOUNTAIN ENCLAVE OF EXCEPTIONAL BEAUTY AND BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY. IF YOU LOVE UNSPOILT NATURE AND PRISTINE OPEN SPACES, IN ARAGON YOU WILL FIND WHAT YOU ARE LOOKING FOR. SECLUDED AND ENCHANTING PLACES THAT WILL AWAKEN YOUR IMAGINATION. Wild/ ARAGON and IS NATURE You’ll want to pull onImposing your hiking boots, because the variety and diversity of ecosystems has created stunning and beautiful landscapes, from the high peaks to the river valleys, through the rugged mountain ranges and vast steppes. And in all of them you’ll see yourself as part of a living, breathing world. Aragon is nature. The diversity of its landscapes, teeming with wildlife, makes it an exceptional region in terms of its natural areas. <The Ordesa valley in its autumn finery. Deer in Garcipollera. Pyrenean flowers. Rocas del Masmut in Peñarroya de Tastavins. Poppy field in Somontano /3 IF ANYTHING CHARACTERISES LA SIERRA DE GUARA IT IS ITS MAGNIFICENT CANYONS AND RAVINES, CARVED FROM THE LIMESTONE OVER MILLIONS OF YEARS BY WIND AND WATER. River Vero Cultural Park. 01/ 02/ ARAGON THE PYRENEES IS NATURE AND NATURE The diversity of Aragonese The Aragonese Pyrenees are landscapes, teeming with a symbol of Spain’s natural wildlife, makes this an diversity. The region is home exceptional region in terms of to the highest number of its natural areas. -

Vincent CH Tong Editor Teaching at Universities

Innovations in Science Education and Technology 20 Vincent C.H. Tong Editor Geoscience Research and Education Teaching at Universities Geoscience Research and Education INNOVATIONS IN SCIENCE EDUCATION AND TECHNOLOGY Volume 20 Series Editor Cohen, Karen C. Weston, MA, USA About this Series As technology rapidly matures and impacts on our ability to understand science as well as on the process of science education, this series focuses on in-depth treatment of topics related to our common goal: global improvement in science education. Each research-based book is written by and for researchers, faculty, teachers, students, and educational technologists. Diverse in content and scope, they refl ect the increasingly interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches required to effect change and improvement in teaching, policy, and practice and provide an understanding of the use and role of the technologies in bringing benefi t globally to all. For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/6150 Vincent C.H. Tong Editor Geoscience Research and Education Teaching at Universities Editor Vincent C.H. Tong Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences Birkbeck, University of London London, UK ISSN 1873-1058 ISSN 2213-2236 (electronic) ISBN 978-94-007-6945-8 ISBN 978-94-007-6946-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-6946-5 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013949006 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Climate Early Paleogene

Climate & Biota of the Early Paleogene Bilbao 2006 Organized by: Department of Stratigraphy and Paleontology Faculty of Science and Technology University of the Basque Country Sponsors Provincial Government of Biscay Faculty of Science and Technology University of the Basque Country Basque Government Ministry of Education and Culture of Spain Bilbao Town Council Zumaia Town Council Getxo Town Council Galdakao Town Council Basque Energy Board (EVE) IRIZAR Group The Geological and Mining Institute of Spain (IGME) Bilbao Turismo & Convention Bureau Algorri Research Centre International Subcommission on Paleogene Stratigraphy (ISPS) Edited by: Bernaola Gilen, Baceta Juan Ignacio, Payros Aitor, Orue-Etxebarria Xabier and Apellaniz Estibaliz Contributing authors: Alegret Laia, Angori Eugenia, Apellaniz Estibaliz, Arostegi Javier, Baceta Juan I., Bernaola Gilen, Caballero Fernando, Dinarès-Turell Jaume, Luterbacher Hanspeter, Martín-Rubio Maite, Monechi Simonetta, Nuño-Arana Yurena, Ortiz Silvia, Orue-Etxebarria Xabier, Payros Aitor, Pujalte Victoriano We recomend to reference this book as follows: Bernaola G., Baceta J.I., Payros A., Orue-Etxebarria X. and Apellaniz E. (eds.) 2006. The Paleocene and lower Eocene of the Zumaia section (Basque Basin). Climate and Biota of the Early Paleogene 2006. Post Conference Field Trip Guidebook. Bilbao, 82p. Baceta J.I., Bernaola G. and Arostegi J. 2006. Lithostratigraphy of the Mid-Paleocene interval at Zumaia section. In: Bernaola G., Baceta J.I., Payros A., Orue-Etxebarria X. and Apellaniz E. (eds.) 2006. The Paleocene and lower Eocene of the Zumaia section (Basque Basin). Climate and Biota of the Early Paleogene 2006. Post Conference Field Trip Guidebook. Bilbao, 82p. Printed by: KOPIAK. Bilbao ISBN: 84-689-8940-1 D.L..: May 2006 Venue Palacio Euskalduna Conference Centre and Concert Hall BILBAO. -

Demography Reveals Populational Expansion of a Recently Extinct Iberian Ungulate

Zoosyst. Evol. 97 (1) 2021, 211–221 | DOI 10.3897/zse.97.61854 Demography reveals populational expansion of a recently extinct Iberian ungulate Giovanni Forcina1, Kees Woutersen2, Santiago Sánchez-Ramírez3, Samer Angelone4, Jean P. Crampe5, Jesus M. Pérez6,7, Paulino Fandos7,8, José Enrique Granados7,9, Michael J. Jowers1,10 1 CIBIO/InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrario De Vairão, 4485-661 Vairão, Portugal 2 Calle Ingeniero Montaner, 4-1-C 22004 Huesca, Spain 3 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, 25 Willcocks, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3B2, Canada 4 Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies (IEU), University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, Zurich, Switzerland 5 19 chemin de Peyborde 65400 Lau-Balagnas, France 6 Departamento de Biología Animal, Biología Vegetal y Ecología, Universidad de Jaén, Campus Las Lagunillas, s.n., E-23071 Jaén, Spain 7 Wildlife Ecology & Health group (WE&H), Jaén, Spain 8 Agencia de Medio Ambiente y Agua, E-41092 Sevilla, Isla de la Cartuja, Spain 9 Espacio Natural Sierra Nevada, Carretera Antigua de Sierra Nevada, Km 7, E-18071 Pinos Genil, Granada, Spain 10 National Institute of Ecology, 1210, Geumgang-ro, Maseo-myeon, Seocheon-gun, Chungcheongnam-do, 33657, South Korea http://zoobank.org/382480DE-1CE7-45A7-9C75-21036C7A3560 Corresponding author: Michael J. Jowers ([email protected]) Academic editor: M. TR Hawkins ♦ Received 11 December 2020 ♦ Accepted 9 March 2021 ♦ Published 1 April 2021 Abstract Reconstructing the demographic history of endangered taxa is paramount to predict future fluctuations and disentangle the contribut- ing factors. Extinct taxa or populations might also provide key insights in this respect by means of the DNA extracted from museum specimens. -

Ordesa and Monte Perdido National Park

Council of Europe Conseil de I'Europe * * * * * * * * **** Strasbourg, 10 February 1998 PE-S-DE (98) 56 [s:\de98'docs\de56E.98] COMMITTEE FOR THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE IN THE FIELD OF BIOLOGICAL AND LANDSCAPE DIVERSITY CO-DBP Group of specialists - European Diploma Ordesa and Monte Perdido National Park (Spain) Category A RENEWAL Expertise Report by Mr Charles STAUFFER (France) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribue en reunion. Priere de vous munir de cet exemplaire. PE-S-DE (98) 56 - 2 - No Secretariat representative accompanied the expert on his inspection of the park. Appendix I contains Resolution (93) 16, renewing the European Diploma. Appendix II contains a draft resolution drawn up by the Secretariat for a possible renewal in 1998. - 3- PE-S-DE (98) 56 ORDESA AND MONTE PERDIDO NATIONAL PARK The Ordesa and Monte Perdido National Park was awarded the European Diploma on 13 June 1988. The Diploma was renewed in 1993. The Diploma being scheduled for renewal again in 1998, the Council of Europe's Directorate of Environment and Local Authorities asked me to carry out an on-the-spot appraisal with a view to: ascertaining whether the park continues to fulfil the criteria for a category A Diploma; verifying the implementation of Resolution (93) 16, adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 3 May 1993, as set forth in Appendix I. 1. GENERAL REMARKS Lucien BRIET, born in Paris in 1860, was one of the figures responsible for the creation in 1918 of the Ordesa Valley National Park, covering an area of 2,066 ha. -

Imprescindibles Elige El Recorrido Que Se Adapta a Tus Posibilidades Infórmate Antes De Salir Del Perfil De La Ruta, Altura INFÓRMATE Del Subida, Distancia, Etc

SOBRARBE, PIRINEO ARAGONÉS 27 WALKS AND DAY TRIPS 27 RANDOS ET BALADES EXCURSIONES 27 Y PASEOS Imprescindibles ELIGE EL RECORRIDO QUE SE ADAPTA A TUS POSIBILIDADES Infórmate antes de salir del perfil de la ruta, altura INFÓRMATE DEL subida, distancia, etc. Lleva siempre un mapa. TIEMPO Los cambios bruscos del tiempo en la montaña son frecuentes y se CONOCE pueden dar tormentas, nieve, vien- TUS to, frío, granizo, los cuales pueden LÍMITES hacer que la situación cambie. Mide tus fuerzas y tu capacidad. Nunca te sobrevalores NO VAYAS SOLO Informa a algún familiar, amigo o alojamiento donde estás alojado de CALZADO dónde vas y cuándo piensas volver, Ponte ropa qué ruta vas a hacer, etc. No cam- y calzado bies de itinerario sobre la marcha. 10 adecuado. CONSEJOS DECÁLOGO POCA COMIDA Y DEL EXCURSIONISTA MUCHA AGUA Planifica bien la cantidad de comida y de agua , EL BOTIQUIN debe formar parte de la mochila. Una simple rozadura puede hacer más fatigosa la RESPETA ruta y amargarte la excursión. EL MEDIO Respetar las indicaciones y las normas del espacio natural. ADÁPTATE a las posibilidades del más débil. Tratar las basuras de forma Cada montañero es responsable de sí mismo adecuada. No molestar a las y de sus compañeros, SÉ SOLIDARIO. especies ni alterar el entorno 112 TELÉFONO DE EMERGENCIA 3 SOBRARBE MAPA/CARTE/MAP Tunel de Bielsa a Francia A-138 PARQUE NATURAL SAN NICOLÁS POSETS-MALADETA DE BUJARUELO PARQUE NACIONAL 15 22 PARZÁN 26 14 DE ORDESA Y ESPIERBA MONTE PERDIDO 18 TORLA-ORDESA BIELSA SECTOR a Biescas 16 N-260 13 BAL DE 23 BROTO TELLA