Willd Flowers of Ordesa and Monte Perdido National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ordesa: Del Valle Perdido Al Símbolo Patrimonial 1

EDUARDO MARTÍNEZ DE PISÓN Departamento de Geografía. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Ordesa: del valle perdido al símbolo patrimonial 1 RESUMEN qui a cherché son sens patrimonial tout au long de la première moitié A partir de los relatos de los pirineístas, el valle de Ordesa adquirió du siècle XX. renombre por su apartamiento y calidades naturales. Las amenazas a sus paisajes dieron lugar a una campaña para su protección que coin- ABSTRACT cidió con la creación de los parques nacionales en España (1916). Se Ordesa : from last valley to heritage emblem.- From the accounts of formó allí un espacio protegido de tamaño restringido pero de fama the Pyreneans writers, Ordesa Valley acquired renown by his apartment internacional que buscó su sentido patrimonial a lo largo de la primera and natural qualities. The threats to its landscapes gave place to a cam- mitad del siglo XX. paign for its protection that coincided with the creation of national parks in Spain (1916). There was formed a protected space of restricted RÉSUMÉ size but of international fame that has looked for its heritage meaning Ordesa: de la vallée perdue au symbole patrimonial.- À partir des na- along the first half of the 20th century. rrations des pyrénéistes, la vallée d’Ordesa a acquis de la réputation par son éloignement et ses qualités naturelles. Les menaces à leurs paysa- PALABRAS CLAVE/MOTS CLÉ/KEYWORDS ges ont donné lieu à une campagne pour leur protection qui a coïncidé Ordesa, parque nacional, valor patrimonial. avec la création des parcs nationaux en Espagne (1916). On a formé là Ordesa, parc national, valeur patrimonial. -

Forest Fire Prevention Plans in National Parks: Ordesa Nacional Park and Monte Perdido1

Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Fire Economics, Planning, and Policy: A Global View Forest Fire Prevention Plans in National Parks: Ordesa Nacional Park and Monte Perdido1 Basilio Rada,2 Luis Marquina3 Summary Protected natural spaces contribute to the well being of society in various ways such as maintaining biological diversity and quality of the landscape, regulation of water sources and nutrient cycles, production of soil, protection against natural catastrophes and the provision of recreation areas, education, science and culture, aspects which attain maximum relevance in the lands under the protection of the National Park. The singular nature and the high degree of protection to a large extent limit management, since the principles of conservation and natural processes prevail in these areas. Nevertheless the inevitable responsibility to ensure now and in future, the ecological economic and social functions of these spaces goes on to assume a management model on the lines of compliance with the Pan European Criteria for Sustainable Forest Management. In 2000 management of the Ordesa and Monte Perdido Park , in the Spanish Pyrenees which was declared a natural park in 1918, took the initiative to devise a Plan for the Prevention of Forest Fires in the park and its surroundings which may be a reference for the other parks comprising the network of Spanish National Parks. The Plan analyses the effectiveness of current protection resources, supported by cartography which aids decision making, fuel maps, fire risk, visibility, territorial isochrones and areas which at the same time plan the necessary measures to guarantee the protection of this space, which in many areas is inaccessible due to the steep landscape. -

Map of La Rioja Haro Wine Festival

TRAVEL AROUND SPAIN SPAIN Contents Introduction.................................................................6 General information......................................................7 Transports.................................................................10 Accommodation..........................................................13 Food.........................................................................15 Culture......................................................................16 Region by region and places to visit..............................18 Andalusia........................................................19 Aragon............................................................22 Asturias..........................................................25 Balearic Islands...............................................28 Basque Country................................................31 Canary Islands.................................................34 Cantabria........................................................37 Castille-La Mancha...........................................40 Castille and León.............................................43 Catalonia........................................................46 Ceuta.............................................................49 Extremadura....................................................52 Galicia............................................................55 La Rioja..........................................................58 Madrid............................................................61 -

Discover Sobrarbe 2017.Indd 1 20/07/2017 15:14:33 Introduction

Discover Sobrarbe _2017.indd 1 20/07/2017 15:14:33 Introduction The central Pyrenees, the mountain range spanning from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, is the steepest, wildest and most spectacular part of this land mass. Its highest peaks, its deepest valleys and its glaciers, together with a great variety of habitats hardly altered by human activity, have become the refuge of a great number of animal and plant species. Sobrarbe, one of the boroughs of the province of Huesca, spreads over 2,202 square kilometres in the Central Pyrenees and pre-Pyrenean ranges and includes the River Ara basin and the River Cinca headwaters and its tributaries. Cave paintings, dolmens and other findings show us that this land was populated in the Neolithic age. The Romans arrived many centuries later, then the Visigoths and later still the Moslems, who were expelled in the 10th century. There were hard times for the people of Sobrarbe although in the 16th century there was a period of prosperity. The 20th century brought about great improvements (investments, road networks) and great disasters (Civil War, eservoirs, depopulation…). Around 7,500 people live in Sobrarbe, most of whom work either inagriculture or in the service sector. They live in a privileged area ofgreat beauty. Sobrarbe aims at sustainable development according to the parameters of the Local Agenda 21. This guide is an invitation to walk through this area and learn about its history, its villages, its landscape and its people. Just a few clues will lead you to enjoy many of Sobrarbe’s beauty spots. -

3. Cueva De Chaves .87 3.1

NICCOLÒ MAZZUCCO The Human Occupation of the Southern Central Pyrenees in the Sixth-Third Millennia cal BC: a Traceological Analysis of Flaked Stone Assemblages TESIS DOCTORAL DEPARTAMENT DE PREHISTÒRIA FACULTAT DE LETRES L Director: Dr. Ignacio Clemente-Conte Co-Director: Dr. Juan Francisco Gibaja Bao Tutor: Dra. Maria Saña Seguí Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2014 This work has been founded by the JAE-Predoc scholarship program (year 2010-2014) of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), realized at the Milà i Fontanals Institution of Barcelona (IMF). This research has been carried out as part of the research group “Archaeology of the Social Dynamics” (Grup d'Arqueologia de les dinàmiques socials) of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology of the IMF. Moreover, the author is also member of the Consolidated Research Group by the Government of Catalonia “Archaeology of the social resources and territory management” (Arqueologia de la gestió dels recursos socials i territori - AGREST 2014-2016 - UAB-CSIC) and of the research group “High-mountain Archaeology” (Grup d'Arqueologia d'Alta Muntanya - GAAM). 2 Todos los trabajos de arqueología, de una forma u otra, se podrían considerar trabajos de equipo. Esta tesis es el resultado del esfuerzo y de la participación de muchas personas que han ido aconsejándome y ayudándome a lo largo de su desarrollo. Antes de todo, quiero dar las gracias a mis directores, Ignacio Clemente Conte y Juan Francisco Gibaja Bao, por la confianza recibida y, sobre todo, por haberme dado la posibilidad de vivir esta experiencia. Asimismo, quiero extender mis agradecimientos a todos los compañeros del Departamento de Arqueología y Antropología, así como a todo el personal de la Milà i Fontanals. -

Flora Y Vegetación Del Parque Nacional De Ordesa Y Monte Perdido (Sobrarbe, Pirineo Central Aragonés)

Universidad de Barcelona Facultad de Biología Departamento de Biología Vegetal Flora y vegetación del Parque Nacional de Ordesa y Monte Perdido (Sobrarbe, Pirineo central aragonés) Bases científicas para su gestión sostenible Memoria presentada por José Luis Benito Alonso, licenciado en Biología, para optar al grado de Doctor en Biología Programa de doctorado “Vegetales y fitocenosis”, curso 1994/96 Abril de 2005 Flora y vegetación del Parque Nacional de Ordesa y Monte Perdido 3. Vegetación CAPÍTULO 3. VEGETACIÓN ......................................................................................... 313 1. Introducción................................................................................................................................... 313 2. Catálogo de comunidades vegetales .......................................................................................... 314 2.1. Vegetación de turberas y pastos higroturbosos........................................................................ 314 CL. SCHEUCHZERIO PALUSTRIS-CARICETEA NIGRAE Tüxen 1937 .................................... 314 Or. Caricetalia davallianae Br.-Bl. 1949................................................................................. 314 Al. Caricion davallianae Klika 1934.................................................................................... 314 Al. Caricion maritimae Br.-Bl. in Volk 1940 nom . mut . prop ............................................... 315 2.2. Juncales, herbazales húmedos y prados de siega .................................................................. -

Geological Sciences Alumni Newsletter November 2016 1

GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES ALUMNI NEWSLETTER NOVEMBER 2016 1 ALUMNI NEWSLETTER 2016 Roster From Our Department Chair 2 Assistant Professors Noel Bartlow (Stanford University 2013) Faculty Geophysics and tectonics News 4 John W. Huntley (Virginia Tech, 2007) Research Grants 5 Paleontology and Paleoecology James D. Schiffbauer (Virginia Tech, 2009) Visiting scientists/staff recognition 13 Paleontology and geochemistry Visiting Speakers 14 Associate Professors Martin S. Appold (Johns Hopkins University, 1998) Conference 15 Hydrogeology Francisco G. Gomez (Cornell University, 1999) Field Camp 16 Paleoseismology and neotectonics Research Professors Selly 18 Cheryl A. Kelley (University of North Carolina, 1993) Undergraduate Program 19 Aquatic geochemistry Mian Liu (University of Arizona, 1989) Study Abroad Program 20 Geophysics Kenneth G. MacLeod (University of Washington, 1992) Photo Gallery Paleontology and biogeochemistry Field Trips 23 Field Camp 24 Peter I. Nabelek (SUNY, Stony Brook, 1983) Outreach 25 Trace-element geochemistry Alumni Reunion 26 Eric A. Sandvol (New Mexico State University, 1995) Undergraduate Presentations 27 Seismotectonics Kevin L. Shelton (Yale University, 1982) Students Economic geology La Reunion 28 Alan G. Whittington (Open University, 1997) Soldati Award 29 Crustal petrology and volcanology Geology Club 30 Student Chapter of AEG-AAPG 31 Director of Field Studies MU Geology Graduate Society 32 Miriam Barquero-Molina (University of Texas, 2009) Undergraduate 33 Awards 34 Field methods Graduate 35 Publications 37 Professors Emeriti Presentation 38 Robert L. Bauer (University of Minnesota, 1982) Precambrian geology Development Activities Raymond L. Ethington (University of Iowa, 1958) Activities 40 Conodont biostratigraphy Contributions 41 Thomas J. Freeman (University of Texas, 1962) Endowmenta 43 Carbonate petrology Faculty Awards 45 Glen R. Himmelberg (University of Minnesota, 1965) Board Members 46 From Our Board Chair 47 Chemical petrology Michael B. -

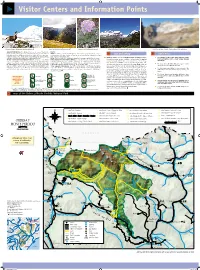

Visitor Centers and Information Points

Visitor Centers and Information Points Pyrenean chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra pyrenaica) Sunset in the Ordesa Valley in early fall Pyrenean violet (Ramonda myconi) Head of the Añisclo Canyon in early spring North face of Monte Perdido. Marboré glacial lake and glacier General Information. The National Park can be reached through the Routes towns of Torla (Ordesa), Escalona and Fanlo (Añisclo), Escuaín and Tel- Trails.The Park has a network of hiking trails. These trails are properly marked, except in tips and safety don’t miss la-Revilla (Escuaín), and Bielsa (Pineta). The National Park is open year- certain sections at higher elevations. There are forest trails that are restricted from use round and entry is free. A wide range of accommodation options (hotels, both in and surrounding the Park. Warning: caution! You are in a high-mountain landscape. At times, The grandeur of the Ordesa Valley, naturally carved cottages, campsites, and hostels) are located near the Park. Hikes. Please contact local specialized companies to arrange a guided hike or ascent. this stunning region can pose a number of different risks. The weather from sedimentary rock to create unique contours Visitor Centers and Information Points. The Park has a main Visitor Public transport to the Ordesa Valley. Access to the Ordesa Valley in private vehicle and shapes. Center in the village of Torla and a sensorium for the physically handi- is prohibited during the summer months and Easter week. A public bus service will provide in mountain ranges like the Pyrenees is unpredictable and can change capped, “Casa Oliván”, located in the Ordesa Valley a kilometer before the transportation to the Park during these times. -

Paintodayspain

SPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAIN- TODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- ALLIANCE OF CIVILIZATIONS PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- 2009 DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- Spain today 2009 is an up-to-date look at the primary PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- aspects of our nation: its public institutions and political scenario, its foreign relations, the economy and a pano- 2009 DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- ramic view of Spain’s social and cultural life, accompanied by the necessary historical background information for PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- each topic addressed DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- http://www.la-moncloa.es PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- SPAIN TODAY TODAY SPAIN DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAIN- TODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- -

Aragon 20000 of Trails

ENGLISH ARAGON 20,000 KM OF TRAILS BEAUTY AND ADVENTURE COME TOGETHER IN ARAGON’S EXTENSIVE NETWORK OF TRAILS. FROM THE HEIGHTS OF THE PYRENEES TO THE BREATHTAKING STEPPES OF THE EBRO AND THE MOST RUGGED MOUNTAIN RANGES ON THE IBERIAN PENINSULA, HERE YOU WILL FIND NATURE AT ITS BEST. HIKING TRAILS OF ARAGON LONG-DISTANCE PATHS THEMED LONG-DISTANCE HIKES WALKS AND EXCURSIONS CLIMBS ACCESIBLE TRAILS Download the app for the Hiking Trails of Aragon and go to senderosturisticos.turismodearagon.com / HIKING TRAILS OF ARAGON 01/ HIKING TRAILS OF ARAGON .................................. 1 02/ INDEX OF TRAILS IN THIS GUIDE .................... 4 03/ LONG-DISTANCE PATHS ........................................ 6 04/ THEMED LONG-DISTANCE HIKES ............... 9 05/ WALKS AND EXCURSIONS ............................... 12 06/ CLIMBS .................................................................................... 28 07/ ACCESSIBLE TRAILS ................................................ 32 Published by: PRAMES Photography: F. Ajona, D. Arambillet, A. Bascón «Sevi», Comarca Gúdar-Javalambre, Comarca Somontano de Barbastro, M. Escartín, R. Fernández, M. Ferrer, D. Mallén, Montaña Segura, M. Moreno, Osole Visual, Polo Monzón, Prames, D. Saz, Turismo de Aragón HIKING IS ONE OF THE BEST WAYS TO GET FIRSTHAND EXPERIENCE OF ALL THE NATURAL AREAS THAT ARAGON HAS TO OFFER, FROM THE SOUTHERNMOST GLACIERS IN EUROPE, FOUND ON THE HIGHEST PEAKS OF THE PYRENEES, TO THE ARID STEPPES OF THE EBRO VALLEY AND THE FASCINATING MOUNTAIN RANGES OF TERUEL. / HIKING TRAILS OF ARAGON In terms of landscapes and natural beauty, Aragon is exceptional. It is famous for the highest peaks in the Pyrenees, with Pico de Aneto as the loftiest peak; the Pre-Pyrenean mountain ranges, with Guara and the Mallos de Riglos as popular destinations for adventure sports worldwide; and the Iberian System, with Mount Moncayo as its highest peak and some of the most breathtakingly rugged terrain in Teruel. -

A Centennial Path Towards Sustainability in Spanish National Parks: Biodiversity Conservation and Socioeconomic Development (1918-2018)

Chapter 8 A Centennial Path Towards Sustainability in Spanish National Parks: Biodiversity Conservation and Socioeconomic Development (1918-2018) DavidDavid Rodríguez-Rodríguez Rodríguez-Rodríguez and JavierJavier Martínez-Vega Martínez-Vega Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.73196 Abstract National Parks (NPs) were the first protected areas (PAs) designated in Spain one century ago. NPs are PAs of exceptional natural and cultural value that are representative of the Spanish natural heritage. Currently, there are 15 NPs in Spain covering almost 400,000 ha, although new site designations are being considered. Spanish NPs’ main objectives are closely linked to the sustainability concept: conserving natural and cultural assets in the long term and promoting public use, environmental awareness, research and socioeco- nomic development. Here, the history of modern nature conservation in Spain is sum- marized, with special focus on NPs. Moreover, the main monitoring and assessment initiatives in Spanish National Parks are reviewed. Finally, the major results of two cur- rent research projects focusing on the sustainability of Spanish NPs, DISESGLOB and SOSTPARK, are provided. Keywords: protected area, assessment, sustainable development, Spain, history 1. Introduction Places set aside to conserve natural resources such as forests, plants, animals (chiefly game animals) or waters have existed for centuries. European and Asian kings and noblemen estab- lished royal reserves or game reserves in their dominions. Those ‘reserves’ forbade or restricted access and use of resources to laymen for pleasure and enjoyment of the privileged, who were entrusted management and conservation of such sites. Modern protected areas (PAs) © 2016 The Author(s). -

1 Key Facts and Figures on the Spain / Unesco Cooperation

Last update: December 2017 KEY FACTS AND FIGURES ON THE SPAIN / UNESCO COOPERATION 1. Membership in UNESCO: since 30 January 1953 2. Membership on the Executive Board: yes, for the period 2015-2019 3. Membership on Intergovernmental Committees, Commissions, etc.: International Coordinating Council of the Programme on Man and the Biosphere (term expires in 2021) Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission 4. The Director-General’s visits to Spain: none 5. The former Director-General’s visits to Spain: 9 23-24 May 2017: to participate in the Madrid International Conference on “Victims of Ethnic and Religious Violence in the Middle East: Protecting and Promoting Plurality and Diversity” 30-31 May 2016: to participate in the 1st International conference on Preventive Diplomacy in the Mediterranean 31 March to 1 April 2015: visit to Valencia to attend the opening session of the “Expert meeting on a model code of ethics for intangible cultural heritage”. The objective of this meeting - convened at the request of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICT) - was to discuss the main lines that should figure into a code of ethics for intangible cultural heritage. This expert meeting (Category 6) was generously hosted by Spain 4-5 April 2014: visit to Catalonia for the signature of an agreement with the Kingdom of Spain regarding the UNESCO Category II International Centre on “Mediterranean Biosphere Reserves, Two Coastlines United by their Culture and Nature” 2-5 April 2013: visit to Madrid