A Cluster-Randomised, Parallel Group, Controlled Intervention Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fællesrådenes Adresser

Fællesrådenes adresser Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail Kirkebakken 23 Beder-Malling-Ajstrup Fællesråd Jørgen Friis Bak [email protected] 8330 Beder Langelinie 69 Borum-Lyngby Fællesråd Peter Poulsen Borum 8471 Sabro [email protected] Holger Lyngklip Hoffmannsvej 1 Brabrand-Årslev Fællesråd [email protected] Strøm 8220 Brabrand Møllevangs Allé 167A Christiansbjerg Fællesråd Mette K. Hagensen [email protected] 8200 Aarhus N Jeppe Spure Hans Broges Gade 5, 2. Frederiksbjerg og Langenæs Fællesråd [email protected] Nielsen 8000 Aarhus C Hastruptoften 17 Fællesrådet Hjortshøj Landsbyforum Bjarne S. Bendtsen [email protected] 8530 Hjortshøj Poul Møller Blegdammen 7, st. Fællesrådet for Mølleparken-Vesterbro [email protected] Andersen 8000 Aarhus C [email protected] Fællesrådet for Møllevangen-Fuglebakken- Svenning B. Stendalsvej 13, 1.th. Frydenlund-Charlottenhøj Madsen 8210 Aarhus V Fællesrådet for Aarhus Ø og de bynære Jan Schrøder Helga Pedersens Gade 17, [email protected] havnearealer Christiansen 7. 2, 8000 Aarhus C Gudrunsvej 76, 7. th. Gellerup Fællesråd Helle Hansen [email protected] 8220 Brabrand Jakob Gade Øster Kringelvej 30 B Gl. Egå Fællesråd [email protected] Thomadsen 8250 Egå Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail [email protected] Nyvangsvej 9 Harlev Fællesråd Arne Nielsen 8462 Harlev Herredsvej 10 Hasle Fællesråd Klaus Bendixen [email protected] 8210 Aarhus Jens Maibom Lyseng Allé 17 Holme-Højbjerg-Skåde Fællesråd [email protected] -

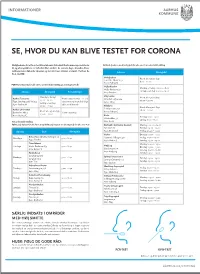

Testmuligheder I Aarhus Kommune

INFORMATIONER SE, HVOR DU KAN BLIVE TESTET FOR CORONA Mulighederne for at få en test bliver løbende forbedret. Der kommer nye teststeder Kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år uden tidsbestilling til, og åbningstiderne er forbedret flere steder i de seneste dage. Desuden bliver testkapaciteten løbende tilpasset og sat ind, hvor smitten er størst. Her kan du Adresse Åbningstid få et overblik: Nobelparken Åbent alle ugens dage Jens Chr. Skous Vej 2 8.00 – 20.00 8000 Aarhus C PCR-Test (I halsen) for alle over 2 år med tidsbestilling på coronaprover.dk Vejlby-Risskov Mandag – fredag: 06.00 – 18.00 Vejlby Centervej 51 Lørdag – søndag: 09.00 – 19.00 Adresse Åbningstid Bemærkninger 8240 Risskov Mandag – fredag: Viby Hallen Aarhus Testcenter Handicapparkering er på Åbent alle ugens dage 07.00 – 21.00 Skanderborgvej 224 Tyge Søndergaards Vej 953 testcentret og man skal følge 08.00 – 20.00 Lørdag – søndag: 8260 Viby J 8200 Aarhus N skiltene til kørende 08.00 – 21.00 Filmbyen Åbent alle ugens dage Aarhus Universitet Filmbyen Studie 1 Åbent alle ugens dage 08.00 – 20.00 Bartholins Allé 3 Handicapvenlig 8000 Aarhus C 09.00 – 16.00 8000 Aarhus C Beder Torsdag: 11:00 - 19:00 Kirkebakken 58 Lørdag: 11:00 - 17:00 Test uden tidsbestilling. 8330 Beder PCR test (i halsen for alle fra 2 år og kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år. Brabrand - Det Gamle Gasværk Mandag: 09.00 – 19.00 Byleddet 2C Tirsdag: 09.00 – 19.00 Ugedag Sted Åbningstid 8220 Brabrand Fredag: 09.00 – 19.00 Harlev Onsdag: 09:00 - 19:00 Beboerhuset Vest’n, Nyringen 1A Mandage 9.00 - 16.30. -

Europe Spotlight On... Denmark, Aarhus &

EUROPE SPOTLIGHT ON... DENMARK, AARHUS & VIA Volume 1 / Issue 3 August 2018 DENMARK DENMARK You may know that the word Denmark is a Scandinavian/Nordic country with around 5.7 million ‘Denmark’ dates back to the inhabitants, a member of the European Union and consists of the Viking age and is carved on peninsula, Jutland, and over 400 islands. Greenland and the Faroe the famous Jelling Stone from Islands are part of the realm but enjoy extensive home rule. around 900 AD. Denmark is one of the world's oldest monarchies with a history that You may even know that stretches back to the Viking Age and its strong welfare state Denmark was a superpower ensures economic equality in society and the virtual non-existence between the 13th and 17th of corruption. Denmark also prides itself on having a healthy work-life balance, which maybe why the Danes are considered to centuries. be one of the happiest people in the world! But did you know that Denmark has an average The Denmark we see today is the result of 400 years of wars and religious and political upheaval. To discover more about Denmark’s wind speed of 7.6 m/s, 406 history you can download a free fact sheet from the official web site islands, 7314 km of coastline of Denmark here: and the highest point in the http://denmark.dk/~/media/Denmark/Documents/Society/History-20 country is only a mere 170m 03-en.pdf?la=en above sea level? Why not visit the official website of Denmark to find out more about Denmark at: http://denmark.dk/en Political map of Denmark. -

Oversigt Over +55 Udlejningsaftaler

Oversigt over +55 udlejningsaftaler I nedenstående boligafdelinger i tabel 1 er der indgået udlejningsaftale, der giver fortrin til et antal boliger til ansøgere, der opfylder følgende kriterium: Personer over 55 år og uden hjemmeboende børn Hvert andet ledige lejemål udlejes til følgende, i prioriteret rækkefølge: 1) Afdelingsinterne 2) Boligorganisationsinterne med fortrin 3) Eksterne med fortrin 4) Boligorganisationsinterne uden fortrin 5) Eksterne uden fortrin Hvert andet ledige lejemål udlejes til følgende, i prioriteret rækkefølge: 1) Ventelisteansøgere med fortrin 2) Ventelisteansøgere uden fortrin Boligorganisation Afdeling Område Brabrand Afd. 10, Rødlundparken 8462 Harlev J Boligforening Afd. 16, Voldbækhave 8220 Brabrand Afd. 22, Sonnesgården 8000 Aarhus C Afd. 23, Skovhøj 8361 Hasselager Afd. 31, Havnehusene 8000 Aarhus C Arbejdernes Andels Afd. 22, Langenæs II 8000 Aarhus C Boligforening Afd. 58, Roukær Alle 8270 Højbjerg Afd. 64, Vintervej 8210 Aarhus V AL2bolig Afd. 123, Søhøjen 8381 Tilst Afd. 125, Tranbjerg Syd (Tingskovparken) 8310 Tranbjerg Afd. 127, Åbyhøjgård 8230 Åbyhøj Alboa Afd. 68, Holme Parkvej 8270 Højbjerg Afd. 70, Jegstrupvej 8361 Hasselager Afd. 72, Klokkeblomstvej 8260 Viby J Afd. 73, Frisenholt 8310 Tranbjerg Afd. 76, Egelundsvej 8260 Viby J Afd. 77, Hvidmosegård 8270 Højbjerg Afd. 79, Pilevangen 8355 Solbjerg Afd. 80, Salamanderparken 8260 Viby J Århus Omegn Afd. 11, Egevangen 8355 Solbjerg Afd. 14, Majsmarken 8520 Lystrup Afd. 17, Skovhøj 8361 Hasselager Boligforeningen Afd. 1, Vestre Ringgade, Tage Hansens Gade, 8000 Aarhus C Ringgården Thomas Nielsens Gade Afd. 4, Silkeborgvej 8000 Aarhus C Afd. 5, Paludan Müllers Vej 8210 Aarhus V Afd. 9, Bildbjerg Parkvej 8200 Aarhus N Afd. 11, Nordre Ringgade 8200 Aarhus N Afd. -

Aarhus University Aarhus Denmark

BENEFICIARY OF MEDEA AARHUS UNIVERSITY AARHUS DENMARK Address Department of Chemistry, Aarhus University Langelandsgade 140 DK-8000 Aarhus C – Denmark Department of Physics and Astronomy, Aarhus University Ny Munkegade 120 DK-8000 Aarhus C – Denmark Scientists in charge Henrik Stapelfeldt +45 871 55974 [email protected] Lars Bojer Madsen +45 871 55636 [email protected] Useful Links www.medea-horizon2020.eu www.chem.au.dk www.phys.au.dk http://phd.au.dk/gradschools/scienceandtechnology Home institution The node at Aarhus University comprises two departments: Department of Chemistry The Department of Chemistry is one of 12 departments at Sci- ence and Technology, Aarhus University. The department houses a number of the Danish National Research Founda- tion’s Centres of Excellence, and carries out teaching tasks for many of the degree programmes at the faculty. Made up of a wide range of scientific areas, the department is expected to be a very strong partner in interdisciplinary initiatives in the future, especially regarding the Interdisciplinary Nanoscience Centre (iNANO). The department’s success is also evident in an analysis recent- ly published by NordForsk. This study measured scientific im- pact by using a citation index to analyse the scientific articles published in the Nordic countries, and the Department of Chemistry was the strongest chemistry institution in the re- gion. The citation rate was more than 50 per cent above aver- age for Denmark and 80 per cent above the Nordic average. The Department of Chemistry also educates the majority of chemists in Denmark, with well over 200 active BSc students, a considerable number of MSc students and more than 100 PhD students. -

Architectural Wonders in Denmark Itinerary

To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Architectural wonders in Denmark To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Land of Architectural Wonders In Denmark, we look for a touch of magic in the ordinary, and we know that travel is more than ticking sights off a list. It’s about finding the wonder in the things you see and the places you go. One of the wonders that we are particularly proud of is our architecture. Danish architecture is world-renowned as the perfect combination of cutting-edge design and practical functionality. We've picked some of Denmark's most famous and iconic buildings that are definitely worth seeing! s. 2 © Robin Skjoldborg, Your rainbow panorama, Olafur Eliasson, 2006 ARoS Aarhus Art Museum To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Denmark and its regions Geography Travel distances Aalborg • The smallest of the Scandinavian • Copenhagen to Odense: Bornholm countries Under 2 hours by car • The southernmost of the • Odense to Aarhus: Under 2 Scandinavian countries hours by car • Only has a physical border with • Aarhus to Aalborg: Under 2 Germany hours by car • Denmark’s regions are: North, Mid, Jutland West and South Jutland, Funen, Aarhus Zealand, and North Zealand and Copenhagen Billund Facts Copenhagen • Video -

Report from CCCA Workshop No. 3 Aarhus University, March 13-14

Report from CCCA Workshop No. 3 Aarhus University, March 13-14, 2019 The workshop is the third of four workshops in the INP network supported by the Danish Agency for Science and Higher Education through the 9th International Network Programme. The International Network Programme is aimed at providing researchers an opportunity to build the foundation for future cooperation and to explore new research partnerships of a potentially high value. The aim for the CCCA network as stated in our application is to develop a platform for scholars, artists, activists, curators, educators, and cultural managers to exchange the experiences and outcomes of socially engaged art movements across borders. Workshop No. 3 focused on the theme of “Site, Material, and Medium in Socially Engaged Art”, and invited contributions that focus on how specific places, various forms of materiality, or different types of mediation contribute to the human interaction and social relations that occur when art projects trigger new types of activities in local communities. Site: Many socially engaged art projects are site specific, calling attention to the local narratives and memory of the place, or they refer to geographical, historical, and political features associated with the site. Material: Participatory and socially engaged artworks may apply certain types of materials as a catalyst for social relations to appear, or relations can occur as “intra-actions” between human and non-human matter. Medium: Media technologies and platforms provide digitized and virtual types of networked relations or infrastructure that may function alongside or in tandem with local and tactile practices. The workshop was organized by Associate Professor Gunhild Borggreen (University of Copenhagen) and hosted by Associate Professor Anemone Platz (Aarhus University). -

European Capital of Culture Aarhus 2017

IMPACT European Capital of Culture Aarhus 2017 2017 was a decisive year in the history of Aarhus The European Capital of Culture title has been of decisive importance to our city, and it has had a great impact on Aarhus and the entire region Aarhus is a city where culture sets the agenda. Culture constitutes a huge part of our identity and self-image In a recently completed survey by analysis known city in Europe to being a European Aarhus 2017 has laid the foundation for brand institute Epinion, the result is clear: 40 % destination that is known in large parts of new inter-municipal collaboration across the of citizens polled in Aarhus indicate that the world. International media coverage region backed by a strong, common desire cultural life is what makes Aarhus a great city has exploded, with major players such as to continue in the future. for all. The year as Capital of Culture has the New York Times, Lonely Planet, Vogue This catalogue presents a review of some made the people of Aarhus even prouder Magazine, The Guardian and many more of the projects and priority areas that the of their city. This is seen in statements mentioning Aarhus as a European city City of Aarhus has decided to participate such as, "I am proud to live in Aarhus" you simply must visit. in. Projects that have had an impact and and "Being a citizen of Aarhus is an The year as European Capital of Culture created a legacy that reaches far beyond important part of my identity". -

Marselisborg Allé 24, 8000 Aarhus

Marselisborg Allé 24, 8000 Aarhus Klassisk Frederiksbjergejendom på hjørnet af Marselisborg Allé og Skt. Pauls Gade Hermed et nyt ejendomsprojekt med en meget flot beboelsesejendom. Ejendommen er beliggende på hjør- net af Marselisborg Allé og Sankt Paul Gade på det attraktive Frederiksbjerg. Ejendommen er bygget i 1898. Det er en smuk hjørneejendom opført i røde mursten. Der er rødt tegltag udført i sadeltagskonstruktion med tagkviste. Ejendommen har endvidere smukke ornamenter omkring vinduerne, og flere af lejlighederne har franske altaner. Foran ejendommen er der en lille hyggelig have. I ejendommens gård er der et baghus, som er udlejet til atelier, ligesom gården kan benyttes af ejendom- mens øvrige beboere til udeliv, cykelparkering m.v. Ejendommen består af 10 lejligheder; 7 stk. 3-værelses i varierende størrelser fra 67 m² til 105 m² og 3 stk. 4-værelses på hver 109 m² samt erhverv i kælder og baghus. Samtlige lejemål er omfattet af Boligregule- ringslovens § 5, stk. 2. Lejlighederne er flotte med klassisk stil som i herskabslejligheder. Flere lejligheder har stuer ”en suite”, men der er også central gennemgang via køkkenet, således de kan bruges af både familier par og som værelser for flere, der gerne vil bo sammen. Der er et smukt view ud overAarhus fra ejendommens øverste lejlighe- der, hvorfra man også kan se vandet. Der er et flot lysindfald i samtlige lejligheder. Der vil være mulighed for at opsætte altaner mod gården, hvor solen kommer hen af eftermiddagen (syd-vestvendt). Der har oprindeligt været altaner fortil på ejendommen. Derfor forventer vi, at det også vil være muligt at genetablere disse, hvorved man også kan opnå altaner, hvor solen vil være i løbet af formid- dagen og for lejlighederne på hjørnet af de to gader – også først på eftermiddagen. -

Anlægskatalog Mobilitet Frem Mod 2050

ANLÆGSKATALOG MOBILITET FREM MOD 2050 VEJNETTET INTELLIGENTE TRANSPORTSYSTEMER KOLLEKTIV TRAFIK CYKLING OG GANG INDLEDNING Anlægskataloget beskriver 71 projekter, der – enkeltvist og Nogle af projekterne i Anlægskataloget er allerede besluttet, og samlet - kan medvirke til at sikre en forbedring af mobiliteten i finansieringen er aftalt. Disse projekter er inkluderet i Anlægska- Aarhus Kommune. Projekterne er præsenteret (gruppevist) i fire taloget for at give et samlet billede af projekter, der kan forbedre indsatsområder: Vejnettet, Intelligente TransportSystemer, mobiliteten frem mod 2050. De besluttede projekter er i anlægs- Kollektiv trafik samt Cykling og gang. overslaget markeret med teksten ” BESLUTTET”. I ”Mobilitet frem mod 2050 – Investeringsbehov og hand- For hvert projektforslag i Anlægskataloget er der anført et lingskatalog” (september 2019) findes en beskrivende tekst anlægsoverslag over udgifterne. Da nogle projekter er meget til de fire indsatsområder. I handlingskataloget anbefales det, bearbejdede i forhold til andre, er der en stor forskel på, hvor hvornår projekterne med fordel kan udføres. I handlingskataloget præcist anlægsoverslagets beløb kan angives. Ved projekter, der er projekterne opdelt efter, om de anbefales udført på kort sigt ikke er detaljerede, vil der derfor ofte stå ”Groft anlægsoverslag”, (0-10 år), mellem sigt (10-20 år) eller med et langt sigte frem hvilket angiver, at projektafklaringer kan medføre markante mod 2050. justeringer af prisen. Projekterne i Anlægskataloget er præsenteret i en ikke prioriteret Effekten af de enkelte projekter er ikke vurderet ved alle projek- rækkefølge. ter. Effekten skal vurderes forud for endelig vedtagelse. ORDFORKLARING: I Anlægskataloget er hvert projekt beskrevet med en kortfattet tekst med et tilhørende oversigtskort samt et anlægsover- slag. I teksterne indgår fagtermer. -

VIA University College

Meet the world VIA University College VIA University College Name of Institution VIA University College Erasmus Code DK RISSKOV06 Head of Institution Harald Mikkelsen Rector Contact T: +45 87 55 00 00 E: [email protected] W: en.via.dk Address VIA has 8 main campuses Aarhus Campus C Ceresbyen 24 DK-8000 Aarhus C T: +45 87 55 00 10 Therese Nørgreen: [email protected] Anne-Mette Nystrøm: [email protected] Filmbyen 4 DK-8000 Aarhus C T. +45 87 55 00 00 Rikke Hedegaard Thomsen: [email protected] Aarhus Campus N Hedeager 2 DK-8200 Aarhus N T: +45 87 55 00 00 Anna Kronborg Bell: [email protected] Camilla Kjærholdt Israelsen: [email protected] Campus Horsens Chr. M. Østergaards Vej 4 DK-8700 Horsens T.: +45 87 55 40 00 Hanne Miller: [email protected] Lise Hjerrild: [email protected] Monika Matula Lauritsen: [email protected] Campus Herning Birk Centerpark 5 DK-7400 Herning T: + 45 87 55 05 00 Louise Bruun Risvang: [email protected] Campus Viborg Prinsens Allé 2 DK-8800 Viborg T: +45 87 55 00 25 Birgitte Vigsø Henningsen: [email protected] The Animation Workshop Kasernevej 5 DK-8800 Viborg T: +45 87 55 49 00 Birgitte Vigsø Henningsen: [email protected] Campus Holstebro Gl. Struervej 1 DK-7500 Holstebro T.: +45 87 55 00 30 Alice Randi Hansen: [email protected] Campus Randers Jens Otto Krags Plads 3 DK-8900 Randers C T.: +45 87 55 00 15 Alice Randi Hansen: [email protected] BA Programmes in English Architectural Technology & Construction Management VIA University College offers full degree programmes Character Animation within animation, business, construction, design, Civil Engineering engineering and health. -

A Visionary Approach to Property Development Projects About Innovater

A VISIONARY APPROACH TO PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS ABOUT INNOVATER Among Denmark’s most experienced property developers, the people behind Innovater have particular expertise in the retail property sector. Since 2008, Innovater has developed in excess of 220,000 sqm distributed on more than 100 different projects for clients across Denmark. At Innovater, we Thanks to our strong and highly skilled network, we can take responsibility always muster the most qualified team for the job. Innovater always maintains project and management control throughout the entire project. for our “actions and While we work very closely with retail chains, we we answer to our also manage projects involving new construction and refurbishment of local retail centres, housing projects and urban development projects and collaboration clients. with social housing associations combining retail, commercial and residential units. Our ambition is to be the preferred partner and to continuously develop our services and capabilities, so we can continue to provide the best solutions and the best locations for our clients. Genua House, Snekkersten 2 3 TAKING A PROJECT FROM IDEA TO COMPLETION Elgiganten, Skejby Innovater manages the entire complex process, starting with a greenfield site or a property in need of a little TLC and seeing the project through until completion with new shops, residential units and infrastructure. A project typically starts with an exploration aimed at identifying a potential project. Innovater prepares an analysis of the area, clarifying customer basis, potential competitors, planning conditions and traffic flows. AUTHORITIES Working with the authorities is part of our core expertise at Innovater. We have strong relationships with municipal authorities and the advisers needed in the development of local planning and zoning activities.