Gender As Compromise Formation : Towards a Radical Psychoanalytic Theory of Trans*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color Maureen Grace White University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color Maureen Grace White University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Educational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation White, Maureen Grace, "Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 182. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/182 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESILIENCY FACTORS AMONG TRANSGENDER PEOPLE OF COLOR by Maureen G. White A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Psychology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT RESILIENCY FACTORS AMONG TRANSGENDER PEOPLE OF COLOR by Maureen G. White The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Dr. Shannon Chavez-Korell Much of the research on transgender individuals has been geared towards identifying risk factors including suicide, HIV, and poverty. Little to no research has been conducted on resiliency factors within the transgender community. The few research studies that have focused on transgender individuals have made little or no reference to transgender people of color. This study utilized the Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) approach to examine resiliency factors among eleven transgender people of color. -

Opening the Door Transgender People National Center for Transgender Equality

opening the door the opening The National Center for Transgender Equality is a national social justice people transgender of inclusion the to organization devoted to ending discrimination and violence against transgender people through education and advocacy on national issues of importance to transgender people. www.nctequality.org opening the door NATIO to the inclusion of N transgender people AL GAY AL A GAY NATIO N N D The National Gay and Lesbian AL THE NINE KEYS TO MAKING LESBIAN, GAY, L Task Force Policy Institute ESBIA C BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ORGANIZATIONS is a think tank dedicated to E N FULLY TRANSGENDER-INCLUSIVE research, policy analysis and TER N strategy development to advance T ASK FORCE F greater understanding and OR equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual T and transgender people. RA N by Lisa Mottet S G POLICY E and Justin Tanis N DER www.theTaskForce.org IN E QUALITY STITUTE NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE POLICY INSTITUTE NATIONAL CENTER FOR TRANSGENDER EQUALITY this page intentionally left blank opening the door to the inclusion of transgender people THE NINE KEYS TO MAKING LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ORGANIZATIONS FULLY TRANSGENDER-INCLUSIVE by Lisa Mottet and Justin Tanis NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE POLICY INSTITUTE National CENTER FOR TRANSGENDER EQUALITY OPENING THE DOOR The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute is a think tank dedicated to research, policy analysis and strategy development to advance greater understanding and equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender -

The Danish Girl - Coming to Blu- Ray™ & Dvd June 20

Jun 14, 2016 15:11 CEST THE DANISH GIRL - COMING TO BLU- RAY™ & DVD JUNE 20 Stockholm, Sweden, June 14, 2016 – With love comes the courage to be yourself in The Danish Girl,coming to Blu-ray™ & DVD on June 20, 2016, from Universal Pictures Home Entertainment. Inspired by the lives of Lili Elbe and Gerda Wegener, the remarkable love story is “a cinematic landmark,” according to Variety’s Peter Debruge. The Danish Girl on Blu-ray™ and DVD comes with an exclusive behind-the-scenes featurette about the making of the film. The film was nominated for four Academy Awards® including Best Actor (Eddie Redmayne), Best Supporting Actress (Alicia Vikander - WINNER), Best Costume Design (Paco Delgado), and Best Production Design (Production Designer, Eve Stewart; Set Decorator, Michael Standish). Academy Award® winner Eddie Redmayne (The Theory of Everything) and Academy Award® winner Alicia Vikander (Ex Machina) star for Academy Award®-winning director Tom Hooper (The King’s Speech and Les Misérables). In the 1920s, a strong and loving marriage evolves as Gerda Wegener (Vikander) supports Lili Elbe (Redmayne) during her journey as a transgender woman. Through the other, each of them finds the courage to be who they are at heart. “Eddie Redmayne and Alicia Vikander are sensational!” declares Access Hollywood’s ScottMantz, while Debruge of Variety raves, “Redmayne gives the greatest performance of his career.” Also starring Ben Whishaw (Skyfall), Sebastian Koch (Homeland), Amber Heard (Zombieland), and Matthias Schoenaerts (Far from the Madding Crowd), The Danish Girl is a moving and sensitive portrait that Lou Lumenick of The New York Post calls “a remarkable and timely story.” BLU-RAY™ & DVD BONUS FEATURE: • The Making of The Danish Girl – Eddie Redmayne, Alicia Vikander, Tom Hooper, and others on the filmmaking team share some of the creative processes that enhanced the beauty of the movie. -

University LGBT Centers and the Professional Roles Attached to Such Spaces Are Roughly

INTRODUCTION University LGBT Centers and the professional roles attached to such spaces are roughly 45-years old. Cultural and political evolution has been tremendous in that time and yet researchers have yielded a relatively small field of literature focusing on university LGBT centers. As a scholar-activist practitioner struggling daily to engage in a critically conscious life and professional role, I launched an interrogation of the foundational theorizing of university LGBT centers. In this article, I critically examine the discursive framing, theorization, and practice of LGBT campus centers as represented in the only three texts specifically written about center development and practice. These three texts are considered by center directors/coordinators, per my conversations with colleagues and search of the literature, to be the canon in terms of how centers have been conceptualized and implemented. The purpose of this work was three-fold. Through a queer feminist lens focused through interlocking systems of oppression and the use of critical discourse analysis (CDA) 1, I first examined the methodological frameworks through which the canonical literature on centers has been produced. The second purpose was to identify if and/or how identity and multicultural frameworks reaffirmed whiteness as a norm for LGBT center directors. Finally, I critically discussed and raised questions as to how to interrupt and resist heteronormativity and homonormativity in the theoretical framing of center purpose and practice. Hired to develop and direct the University of Washington’s first lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT2) campus center in 2004, I had the rare opportunity to set and implement with the collaboration of queerly minded students, faculty, and staff, a critically theorized and reflexive space. -

Reading Group Notes the Danish Girl 2 Curious, I Went to the New York Public Library and Began to Search for References to Einar Wegener

N O T E S F O R pic here R E A D I N G THE DANISH GIRL by David Ebershoff G Contents R About David Ebershoff .......................................................... 2 O A conversation with David Ebershoff ........................................ 2 U Reviews............................................................................. 7 P Some suggested points for discussion ..................................... 11 S Further reading ................................................................. 11 About David Ebershoff David Ebershoff was born in Pasadena, California and is a graduate of Brown University and the University of Chicago. He has also studied at Keio University in Tokyo. He currently lives in New York City where he is the Publishing Director of the Modern Library, a division of Random House. The Danish Girl is Ebershoff ’s first novel. He spent two years writing it during his vacations from Random House and made headlines when the unfinished novel created a bidding war between five interested publishers. Viking won the rights for a reported US$350 000 two-book deal, which also included publishing his first collection of short stories. The Danish Girl has racked up an impressive sale of foreign rights, with eleven countries publishing translations of the novel. Several film studios and actors have also expressed interest in the film rights, including DreamWorks, Angelina Jolie, and Ally McBeal co-star, Gil Bellows. Ebershoff ’s new work, The Rose City (published by Allen & Unwin in August 2001) combines vivid characters with Ebershoff ’s trademark emotional insight and lush prose in seven stories about young men and boys making their way in a chaotic world. He is currently writing his second novel, Pasadena. A Conversation with David Ebershoff How did you discover the story of Einar, Greta, and Lili? A few years ago, a friend who works at a university press mailed me a book about gender theory that his press was publishing. -

Science in Context Fear and Envy: Sexual Difference and The

Science in Context http://journals.cambridge.org/SIC Additional services for Science in Context: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Fear and Envy: Sexual Difference and the Economies of Feminist Critique in Psychoanalytic Discourse José Brunner Science in Context / Volume 10 / Issue 01 / March 1997, pp 129 - 170 DOI: 10.1017/S0269889700000302, Published online: 26 September 2008 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0269889700000302 How to cite this article: José Brunner (1997). Fear and Envy: Sexual Difference and the Economies of Feminist Critique in Psychoanalytic Discourse. Science in Context, 10, pp 129-170 doi:10.1017/ S0269889700000302 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/SIC, IP address: 109.66.70.204 on 12 Feb 2014 Science in Context 10, I (1997), pp. 129-170 JOSfiBRUNNER Fear and Envy: Sexual Difference and the Economies of Feminist Critique in Psychoanalytic Discourse The Argument This essay examines Freud's construction of a mythical moment during early childhood, in which differences between male and female sexual identities are said to originate. It focuses on the way in which Freud divides fear and envy between the sexes, allocating the emotion of (castration) fear to men, and that of (penis) envy to women. On the one hand, the problems of this construction are pointed out, but on the other hand, it is shown that even a much-maligned myth may still provide food for thought. Then, four critiques of Freud which have been articulated by prominent feminist psychoanalysts — Karen Horney, Nancy Chodorow, Luce Irigaray, and Jessica Benjamin — are presented, as well as the alternative visions of sexual identities which these thinkers have developed. -

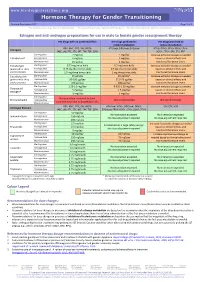

Hormone Therapy for Gender Transitioning Revised September 2017 Page 1 of 2 for Personal Use Only

www.hiv-druginteractions.org Hormone Therapy for Gender Transitioning Revised September 2017 Page 1 of 2 For personal use only. Not for distribution. For personal use only. Not for distribution. For personal use only. Not for distribution. Estrogen and anti-androgen preparations for use in male to female gender reassignment therapy HIV drugs with no predicted effect HIV drugs predicted to HIV drugs predicted to inhibit metabolism induce metabolism RPV, MVC, DTG, RAL, NRTIs ATV/cobi, DRV/cobi, EVG/cobi ATV/r, DRV/r, FPV/r, IDV/r, LPV/r, Estrogens (ABC, ddI, FTC, 3TC, d4T, TAF, TDF, ZDV) SQV/r, TPV/r, EFV, ETV, NVP Starting dose 2 mg/day 1 mg/day Increase estradiol dosage as needed Estradiol oral Average dose 4 mg/day 2 mg/day based on clinical effects and Maximum dose 8 mg/day 4 mg/day monitored hormone levels. Estradiol gel Starting dose 0.75 mg twice daily 0.5 mg twice daily Increase estradiol dosage as needed (preferred for >40 y Average dose 0.75 mg three times daily 0.5 mg three times daily based on clinical effects and and/or smokers) Maximum dose 1.5 mg three times daily 1 mg three times daily monitored hormone levels. Estradiol patch Starting dose 25 µg/day 25 µg/day* Increase estradiol dosage as needed (preferred for >40 y Average dose 50-100 µg/day 37.5-75 µg/day based on clinical effects and and/or smokers) Maximum dose 150 µg/day 100 µg/day monitored hormone levels. Starting dose 1.25-2.5 mg/day 0.625-1.25 mg/day Increase estradiol dosage as needed Conjugated Average dose 5 mg/day 2.5 mg/day based on clinical effects and estrogen† Maximum dose 10 mg/day 5 mg/day monitored hormone levels. -

Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12695 Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction Nick Drydakis OCTOBER 2019 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12695 Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction Nick Drydakis Anglia Ruskin University, University of Cambridge and IZA OCTOBER 2019 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 12695 OCTOBER 2019 ABSTRACT Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction For trans people (i.e. people whose gender is not the same as the sex they were assigned at birth) evidence suggests that transitioning (i.e. -

LGBTQ Notion Evaluation: a Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Summer 6-15-2021 LGBTQ Notion Evaluation: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review Poonam Gautam University School of Management, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, HARYANA INDIA, [email protected] Dr. Ajay Solkhe University School of Management, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, HARYANA INDIA, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Human Resources Management Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons, and the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Gautam, Poonam and Solkhe, Dr. Ajay, "LGBTQ Notion Evaluation: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review" (2021). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 5886. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5886 1 LGBTQ Notion Evaluation: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review Poonam (Main Author) Junior Research Fellow University School of Management, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra-136118, Haryana, INDIA [email protected] Dr. Ajay Solkhe, (Corresponding Author) Sr. Assistant Professor University School of Management, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra-136118, Haryana, INDIA [email protected] Mobile: 9896544852 Abstract Several conservative sectors and employers are embracing equality objectives, including financial institutions, for example, more importantly, there has been a change in attitude and support towards the LGBT+ issues, which has been noticed in other professions and companies, including law and accountancy. The LGBT group includes Lesbians, Gay, Bisexuals and Transgender sexual orientation. Gay men and heterosexuals have also been observed to be in these groups. -

Sylvia Rivera 7/2/1951 – 2/19/2002

SYLVIA RIVERA 7/2/1951 – 2/19/2002 Gay civil rights pioneer Sylvia Rivera was one of the instigators of the Sylvia Rivera, then a 17-year-old drag queen, was among the crowd that gathered outside the Stonewall Inn the night of June 27, 1969, when the New York police raided Stonewall uprising, an the popular Greenwich Village gay bar. Rivera reportedly shouted, “I’m not missing a event that helped launch minute of this, it’s the revolution!” As the police escorted patrons from the bar, Rivera the modern gay rights was one of the first bystanders to throw a bottle. movement. After Stonewall, Rivera joined the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) and worked energetically on its campaign to pass the New York City Gay Rights Bill. She was famously arrested for climbing the walls of City Hall in a dress and high heels to crash a closed-door meeting on the bill. In time, the GAA eliminated drag and transvestite concerns from their agenda as they sought to broaden their political base. Years later, Rivera told an interviewer, “When things started getting more mainstream, it was like, ‘We don’t need you no more.’ ” She added, “Hell hath no fury like a drag queen scorned.” Born Ray Rivera Mendosa, Sylvia Rivera was a persistent and vocal advocate for transgender rights. Her activist zeal was fueled by her own struggles to find food, shelter and safety in the urban streets from the time she left home at age 10. In 1970, Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson co-founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) to help homeless youth. -

Psychologist– Psychoanalyst

Psychologist– ψ Official Publication of Division 39 of the American Psychoanalyst Psychological Association Volume XXIV, No. 4 Fall 2004 FROM THE PRESIDENT JAINE DARWIN, PSYD My route to psychoanalysis began as a student teacher at and not an independent profession. We’ve been supporting Bettelheim’s Orthogenic School as part of a masters pro- our membership in New York State, where psychoanalysts gram in education at the University of Chicago in 1969-70. can be independently licensed without a mental health When I announced to my class I would be leaving at the degree, to push for standards for training in the regulations end of the term, an eight-year-old asked me how long I which we hope will protect the public from an inadequate had been at the school. When I replied that I’d been there treatment that can be called psychoanalysis. We continue for fourteen weeks, he said, “That’s much too short for so to participate in The Working Group on Psychodynamic long.” I feel much the same way as I write this final column Approaches to Classification spearheaded by Stanley of my presidency. I am both sad and eager to say goodbye Greenspan, which hopes to produce a diagnostic manual to the privilege and responsibility of leading Division 39. that utilizes a psychodynamic approach to the classification We’ve accomplished much in the past two years. of mental health disorders. The completion of a first draft is My presidential initiatives included ideas that came under anticipated in Spring 2005. the headings of Outreach and Inreach. -

Queer Censorship in US LGBTQ+ Movements Since World War II

History in the Making Volume 13 Article 6 January 2020 A Different Kind of Closet: Queer Censorship in U.S. LGBTQ+ Movements since World War II James Martin CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, James (2020) "A Different Kind of Closet: Queer Censorship in U.S. LGBTQ+ Movements since World War II," History in the Making: Vol. 13 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol13/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Different Kind of Closet: Queer Censorship in U.S. LGBTQ+ Movements since World War II By James Martin Abstract: Since World War II, there has been an increased visibility of LGBTQ+ communities in the United States; however, this visibility has noticeably focused on “types” of queer people – mainly white, middle class, cisgender gays and lesbians. History remembers the 1969 Stonewall Inn riots as the catalyst that launched the movement for gay rights and brought forth a new fight for civil and social justice. This paper analyzes the restrictions, within LGBTQ+ communities, that have been placed on transpersons and gender nonconforming people before and after Stonewall. While the riots at the Stonewall Inn were demonstrative of a fight ready to be fought, there were many factors that contributed to the push for gay rights.