ABORIGINAL LITERACY and LEARNING Annotated Bibliography & Native Languages Reference Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOSM Activity Report Dr

NOSM Activity Report Dr. Roger Strasser, Dean-CEO January-February 2019 NOSM Announces Incoming Dean and CEO Dr. Sarita Verma appointed as Medical School’s next leader. The Northern Ontario School of Medicine (NOSM) is pleased to announce the appointment of Dr. Sarita Verma as Dean and CEO of NOSM effective July 1, 2019. The NOSM Board of Directors unanimously approved the appointment on December 12, 2018. “We are thrilled to welcome Dr. Verma to NOSM and to the wider campus of Northern Ontario,” says Dr. Pierre Zundel, Chair of the NOSM Board of Directors and Interim President and Vice Chancellor of Laurentian University. “Dr. Verma’s passion, vision and experience will continue to propel NOSM toward world leadership in distributed, community-engaged and socially accountable medical education.” Dr. Verma is currently Vice President, Education at the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada (AFMC) and until January 2016, was Associate Vice-Provost, Relations with Health Care Institutions and Special Advisor to the Dean of Medicine at the University of Toronto. Formerly the Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Medicine (2008-2015) and Associate Vice-Provost, Health Professions Education (2010- 2015), she is a family physician who originally trained as a lawyer at the University of Ottawa (1981) and later completed her medical degree at McMaster University (1991). “I’m grateful to the Board for the opportunity to lead this incredible medical school, and honoured to continue with the momentum created in the past 15 years,” says Dr. Sarita Verma. “I am deeply committed to serving the people of Northern Ontario, to leading progress in Indigenous and Francophone health and cultivating innovation in clinical research.” Dr. -

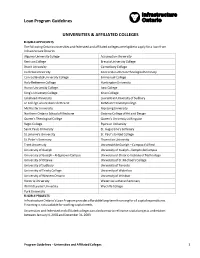

Loans Guidelines

Loan Program Guidelines UNIVERSITIES & AFFILIATED COLLEGES ELIGIBLE APPLICANTS The following Ontario universities and federated and affiliated colleges are eligible to apply for a loan from Infrastructure Ontario: Algoma University College Assumption University Renison College Brescia University College Brock University Canterbury College Carleton University Concordia Lutheran Theological Seminary Conrad Grebal University College Emmanuel College Holy Redeemer College Huntington University Huron University College Iona Coll ege King’s University College Knox College Lakehead University Laurentian University of Sudbury Le Collège universitaire de Hearst McMaster Divinity College McMaster University Nipissing University Northern Ontario School of Medicine Ontario College of Art and Design Queen’s Theological College Queen’s University at Kingston Regis College Ryerson University Saint Pauls University St. Augustine’s Seminary St. Jerome’s University St. Paul’s United College St. Peter’s Seminary Thorneloe University Trent University Université de Guelph – Campus d’Alfred University of Guelph University of Guelph – Kemptville Campus University of Guelph – Ridgetown Campus University of Ontario Institute of Technology University of Ottawa University of St. Michael’s College University of Sudbury University of Toronto University of Trinity College University of Waterloo University of Western Ontario University of Windsor Victoria University Waterloo Lutheran Seminary Wilfrid Laurier University Wycliffe College York University ELIGIBLE PROJECTS -

Oneida Cultural Heritage Department Saving Our Oneida Language

Oneida Cultural Heritage Department By: Dr. Carol Cornelius and Judith L. Jourdan Edit, Revision, and Layout: Tiffany Schultz (09/13) Saving Our Oneida Language INTRODUCTION • All Oneida nation governmental By: Dr. Carol Cornelius meetings to conduct the business of the The Oneida Language Revitalization people were in Oneida Program began in the spring of 1996 in 1600’s response to a national crisis, a state of • The arrival of the French, Dutch, and emergency, in which a survey indicated there English began to impact our economy were only 25-30 Elders left who had learned to and these European languages were speak Oneida as their first language. learned by a few Oneida people in When many of us were very young, we order to conduct trade. heard Oneida spoken all the time by our Elders. 1700’s We must ensure that our little ones now hear • 1709 – Queen Anne ordered that the and learn to speak Oneida. As a Nation we have Common Prayer Book be translated into an urgent need to produce speakers to continue the Mohawk language. This was done Oneida Language. by Eleazer Williams in 1800. As a result of the survey taken, a ten • 1750 – Samuel Kirkland began year plan was developed to connect Elders with missionary efforts which impacted our trainees in a semi-immersion process which language. Many Oneida supported the would produce speakers and teachers of the Americans in the American Revolution. Oneida language. The goal was to hear our 1820’s Oneida language spoken throughout our • Eleazor William’s land negotiations and community. -

Crown Controlled Corporations

EXHIBIT THREE Crown Controlled Corporations CORPORATIONS WHOSE ACCOUNTS ARE AUDITED BY AN AUDITOR OTHER THAN THE PROVINCIAL AUDITOR, WITH FULL ACCESS BY THE PROVINCIAL AUDITOR TO AUDIT REPORTS, WORKING PAPERS AND OTHER RELATED DOCUMENTS Art Gallery of Ontario Crown Foundation Baycrest Hospital Crown Foundation Big Thunder Sports Park Ltd. Board of Funeral Services Brock University Foundation Carleton University Foundation CIAR Foundation (Canadian Institute for Advanced Research) Canadian Opera Company Crown Foundation Canadian Stage Company Crown Foundation Dairy Farmers of Ontario Deposit Insurance Corporation of Ontario Education Quality and Accountability Office Foundation at Queen’s University at Kingston Grand River Hospital Crown Foundation Lakehead University Foundation Laurentian University of Sudbury Foundation McMaster University Foundation McMichael Canadian Art Collection Metropolitan Toronto Convention Centre Corporation 38 Office of the Provincial Auditor Moosonee Development Area Board Mount Sinai Hospital Crown Foundation National Ballet of Canada Crown Foundation Nipissing University Foundation North York General Hospital Crown Foundation Ontario Casino Corporation Ontario Foundation for the Arts Ontario Hydro Sevices Company Inc. Ontario Mortgage Corporation Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement Board Ontario Pension Board Ontario Power Generation Inc. Ontario Superbuild Corporation Ontario Trillium Foundation Ottawa Congress Centre Royal Botanical Gardens Crown Foundation Royal Ontario Museum Royal Ontario Museum Crown -

French at the University of Ottawa Volume II State of Affairs for Programs and Services in French

University of Ottawa French at the University of Ottawa Volume II State of Affairs for Programs and Services in French Task Force on Programs and Services in French September 2006 www.uOttawa.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 3 2. CURRENT CONTEXT ................................................................. 4 3. UNIVERSITY ENVIRONMENT ..................................................... 6 Profile of university officials.............................................................................. 6 Profile of faculty.............................................................................................. 7 Profile of support staff ..................................................................................... 7 4. ACADEMIC PROGRAMS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA ............ 9 Language of instruction in undergraduate programs ............................................ 9 Language of instruction in undergraduate courses..............................................11 Small-group undergraduate courses .................................................................12 Graduate studies ...........................................................................................13 Immersion programs and courses ....................................................................14 Cooperative education programs......................................................................15 5. RECRUITMENT ACTIVITIES AND SCHOLARSHIPS ....................... 17 Recruitment -

Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers Stephen D. Feeley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Stephen D., "Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4nn0-c987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers Volume I Stephen Delbert Feeley Norcross, Georgia B.A., Davidson College, 1996 M.A., The College of William and Mary, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Delbert F eele^ -^ Approved by the Committee, January 2007 MIL James Axtell, Chair Daniel K. Richter McNeil Center for Early American Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Student Transitions Project WebBased Resources

Ontario Native Education Counselling Association Student Transitions Project WebBased Resources Index Section Content Page 1 Schools and Education Institutions for First Nations, Inuit and Métis 3 ‐ Alternative Schools ‐ First Nations Schools ‐ Post‐Secondary Institutions in Ontario 2 Community Education Services 5 3 Aboriginal Student Centres, Colleges 6 4 Aboriginal Services, Universities 8 5 Organizations Supporting First Nations, Inuit and Métis 11 6 Language and Culture 12 7 Academic Support 15 8 For Counsellors and Educators 19 9 Career Support 23 10 Health and Wellness 27 11 Financial Assistance 30 12 Employment Assistance for Students and Graduates 32 13 Applying for Post‐Secondary 33 14 Child Care 34 15 Safety 35 16 Youth Voices 36 17 Youth Employment 38 18 Advocacy in Education 40 19 Social Media 41 20 Other Resources 42 This document has been prepared by the Ontario Native Education Counselling Association March 2011 ONECA Student Transitions Project Web‐Based Resources, March 2011 Page 2 Section 1 – Schools and Education Institutions for First Nations, Métis and Inuit 1.1 Alternative schools, Ontario Contact the local Friendship Centre for an alternative high school near you Amos Key Jr. E‐Learning Institute – high school course on line http://www.amoskeyjr.com/ Kawenni:io/Gaweni:yo Elementary/High School Six Nations Keewaytinook Internet High School (KiHS) for Aboriginal youth in small communities – on line high school courses, university prep courses, student awards http://kihs.knet.ca/drupal/ Matawa Learning Centre Odawa -

Sahuhlúkhane' Ukwehuwenéha They Learned to Speak It Again

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-10-2018 10:00 AM Sahuhlukhané ’ Ukwehuwenehá They Learned to Speak it Again: An Investigation into the Regeneration of the Oneida Language Rebecca Doxtator The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Debassige, Brent The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Education A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Rebecca Doxtator 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Indigenous Education Commons, Language and Literacy Education Commons, and the Language Description and Documentation Commons Recommended Citation Doxtator, Rebecca, "Sahuhlukhané ’ Ukwehuwenehá They Learned to Speak it Again: An Investigation into the Regeneration of the Oneida Language" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5766. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5766 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This study investigated the significance of the Oneida language to two groups of Oneida speakers and learners in the Onʌyota’á:ka’ Oneida Nation of the Thames community. This study included three research questions: (a) what is the significance of Oneida language to Oneida adult language learners who are seeking to acquire -

APC071017-6.2 University of Windsor Academic Policy Committee

APC071017-6.2 University of Windsor Academic Policy Committee 6.2: University of Windsor’s Grading Scale (Background) Item for: Information Rationale: See attached Page 1 of 9 Received by Senate March 21, 2002 Sa020321-7.5.2.3 7.5.2.3: APC Working Group Report on Re-Evaluation of the University=s Grading Scale Item for: Information Forwarded by: Academic Policy Committee Following the Academic Policy Committee=s appointment of working groups, the Working Group on Evaluating the University=s Grading Scale, consisting of Professor Jeff Berryman, Dr. Sirinimal Withane, Ms. Cathy Maskell and Mr. Jerry McCorkell first met on Tuesday, the 16th of October, 2001 in the Faculty of Law. In addition to the Committee members, Ms. Charlene Yates of the Registrar=s Office was seconded to the Committee to assist it. The Committee members wish to record their thanks to Ms. Yates for her diligence and assistance. At the first meeting of the Committee, the terms of reference were discussed. The main issue placed before the Working Group was to investigate whether the current 13 point grade scale, and corresponding letter grades, used by the University of Windsor disadvantaged our students when applying to graduate programs or other scholarship opportunities. In particular, the Working Group was asked to determine whether there was a widely adopted scale and grading scheme used by other Universities in Canada and North America. It was suggested to the Working Group that the four-point scale is used by more universities in Canada and North America, and that scholarship granting agencies and graduate programs are more familiar with this scale and can therefore make comparisons if student applicants come from a wide variety of academic disciplines as well as universities. -

The Way of the Drum—When Earth Becomes Heart Part I

The Way of the Drum—When Earth Becomes Heart Part I Healing the Tears of Yesterday by the Drum Today: The Oneida Language is a Healing Medicine Grafton Antone As I travelled the path of life, little did I realize the suppression I was experiencing as an Ukwehuwe in my Euro-western formal educational journey. The Western model of human development is linear and has four general domains: emotional, social, physical, and intellectual. This Western model emphasizes physical and intellectual development to meet career standards and personal expectations. The Aboriginal Ukwehuwe model of human development is circular and consists of four parts: emotional, mental, physical, and spiritual. The Elders tell us that, to be fully developed, one must maintain balance in all four of these areas. My story shows my development in the Western model. My perseverance afforded me a certain measure of success, but as I passed through the different stages of life, I could sense that there was something missing in my life that I could not explain or identify. It was not until I began teaching the Oneida Language (Onyota’a:ka) that I realized what the missing links were. This is my story of discovery, reorientation, and balance. The information I will share with you is based on my work with various adult students learning Onyota’a:ka as a Second Language in the Toronto School Board. In 1995-96, the class had a high enrolment of 30, but that gradually fell off to about 15. In 1996-97, the class began at 22 then tapered off to 10. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Guide to the Blair Rudes Papers, 1974-2008, Undated

Guide to the Blair Rudes papers, 1974-2008, undated Tyler Stump The papers of Blair Rudes were processed with the assistance of the Smithsonian Institution's Collections Care and Preservation Fund. April 2016 National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Bibliography...................................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical, 1999-2007........................................................................... 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1975-2007.................................................................... 7 Series 3: Linguistic Research and Data, 1969-2008, undated................................