The Way of the Drum—When Earth Becomes Heart Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oneida Cultural Heritage Department Saving Our Oneida Language

Oneida Cultural Heritage Department By: Dr. Carol Cornelius and Judith L. Jourdan Edit, Revision, and Layout: Tiffany Schultz (09/13) Saving Our Oneida Language INTRODUCTION • All Oneida nation governmental By: Dr. Carol Cornelius meetings to conduct the business of the The Oneida Language Revitalization people were in Oneida Program began in the spring of 1996 in 1600’s response to a national crisis, a state of • The arrival of the French, Dutch, and emergency, in which a survey indicated there English began to impact our economy were only 25-30 Elders left who had learned to and these European languages were speak Oneida as their first language. learned by a few Oneida people in When many of us were very young, we order to conduct trade. heard Oneida spoken all the time by our Elders. 1700’s We must ensure that our little ones now hear • 1709 – Queen Anne ordered that the and learn to speak Oneida. As a Nation we have Common Prayer Book be translated into an urgent need to produce speakers to continue the Mohawk language. This was done Oneida Language. by Eleazer Williams in 1800. As a result of the survey taken, a ten • 1750 – Samuel Kirkland began year plan was developed to connect Elders with missionary efforts which impacted our trainees in a semi-immersion process which language. Many Oneida supported the would produce speakers and teachers of the Americans in the American Revolution. Oneida language. The goal was to hear our 1820’s Oneida language spoken throughout our • Eleazor William’s land negotiations and community. -

Sahuhlúkhane' Ukwehuwenéha They Learned to Speak It Again

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-10-2018 10:00 AM Sahuhlukhané ’ Ukwehuwenehá They Learned to Speak it Again: An Investigation into the Regeneration of the Oneida Language Rebecca Doxtator The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Debassige, Brent The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Education A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Rebecca Doxtator 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Indigenous Education Commons, Language and Literacy Education Commons, and the Language Description and Documentation Commons Recommended Citation Doxtator, Rebecca, "Sahuhlukhané ’ Ukwehuwenehá They Learned to Speak it Again: An Investigation into the Regeneration of the Oneida Language" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5766. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5766 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This study investigated the significance of the Oneida language to two groups of Oneida speakers and learners in the Onʌyota’á:ka’ Oneida Nation of the Thames community. This study included three research questions: (a) what is the significance of Oneida language to Oneida adult language learners who are seeking to acquire -

A Typology of Stress- and Foot-Sensitive Consonantal Phenomena1

A Typology of Stress- and Foot-Sensitive Consonantal Phenomena1 Carolina González Florida State University DOI: https://doi.org/10.1387/asju.18680 Abstract This article investigates consonantal alternations that are conditioned by stress and/ or foot-structure. A survey of 78 languages from 37 language families reveals three types of consonantal phenomena: (i) those strictly motivated by stress (as in Senoufo lengthen- ing), (ii) those exclusively conditioned by foot structure (as in /h/ epenthesis in Huariapano), and (iii) those motivated both by stress and foot structure (as in flapping in American Eng- lish). The fact that stress-only and foot-only consonantal phenomena are attested alongside stress/foot structure conditioned phenomena leads to the proposal that stress and foot struc- ture can work independently, contradicting the traditional view of foot structure organiza- tion as signaled by stress-based prominence. It is proposed that four main factors are at play in the consonantal phenomena under investigation: perception, duration, aerodynamics, and prominence. Duration, aerodynamics and perceptual ambiguity are primarily phonetic, while prominence and other perceptual factors are primarily phonological. It is shown that the mechanism of Prominence Alignment in Optimality Theory captures not only consonan- tal alternations based on prominence, but can also be extended to those with durational and aerodynamic bases. This article also makes predictions regarding unattested stress/foot sensi- tive alternations connected to the four factors mentioned above. Keywords: stress; foot structure; consonantal alternations; phonological typology; percep- tion; duration; aerodynamics; prominence; Prominence Alignment; Optimality Theory. 1 This is a revised version of chapters 1-3 and 6 of my Ph.D. -

ED436973.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 436 973 FL 026 097 AUTHOR Martin, Joyce, Comp. TITLE Native American Languages: Subject Guide. INSTITUTION Arizona State Univ., Tempe. Univ. Library. PUB DATE 1999-08-00 NOTE 12p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: <http://www.asu.edu/lib/archives/labriola.htm> and <http://www.asu.edu/lib/archives/labriola.htm>. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Languages; Biblical Literature; Bilingual Education; Dictionaries; English (Second Language); Indigenous Populations; *Library Guides; Sign Language; Tape Recordings; Uncommonly Taught Languages IDENTIFIERS *Native Americans ABSTRACT This document is an eleven-page supplemental subject guide listing reference material that focuses on Native American languages that is not available in the Labriola National American Indian Data Center in the Arizona State University, Tempe (ASU) libraries. The guide is not comprehensive but offers a selective list of resources useful for developing language and vocabulary skills or researching a variety of topics dealing with native North American languages. Additional material may be found using the ASU online catalogue and the Arizona Southwest index. Contents include: bibles and hymnals; bibliographies; bilingual education, curriculum, and workbooks; culture, history, and language; dictionaries and grammar books; English as a Second Language; guides and handbooks; language tapes; linguistics; online access; sign language.(KFT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Native American Languages Subject Guide The following bibliography lists reference material dealing with Native American languages which is available in the Labriola National American Indian Data Center in the University Libraries. It is not comprehensive, but rather a selective list of resources useful for developing language and vocabulary skills, and/or researching a variety of topics dealing with Native North American languages. -

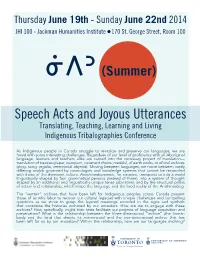

Speech Acts Conference Program 3.Indd

Thursday June 19th - Sunday June 22nd 2014 JHI 100 - Jackman Humanities Institute 170 St. George Street, Room 100 ᓃᐱᐣ (Summer) Speech Acts and Joyous Utterances Translating, Teaching, Learning and Living Indigenous Tribalographies Conference As Indigenous people in Canada struggle to revitalize and preserve our languages, we are faced with some interesting challenges. Regardless of our level of proficiency with an Aboriginal language, learners and teachers alike are carried into the necessary project of translation— translation of treaties (paper, wampum, covenant chains, medals), of earth works, or of oral archives (story, song, regalia, ceremonial objects). Moving between languages, we move between vastly differing worlds governed by cosmologies and knowledge systems that cannot be reconciled with those of the dominant culture. Aniishinaabemowin, for instance, transports us into a world linguistically shaped by four grammatical persons (instead of three), into a system of thought shaped by an additional and linguistically unique tense (obviative), and by the structural pillars of action and relationship, which shape the language and the lived reality of the Anishinaabeg. The “written” archives that have been left for Indigenous peoples across Canada present those of us who labor to recover our cultural legacies with unique challenges and compelling questions as we strive to grasp the layered meanings encoded in the signs and symbols that constitute the histories authored by our ancestors. How are we to engage with these archives? How, -

Developing a Framework for a Minority Language-Based Utility

Developing a Framework for a Minority Language-based Utility by Marco Antonio Monroy Fonseca B.S. Computer Science Instituto Tecnol6gico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey Atizapen, Mexico 1998 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MEDIA TECHNOLOGY AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2002 @ Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2002 All Rights Reserved I' Signature of Author Program in Media Arts and Sciences May 17, 2002 Certified by Walter Bender Senior Research Scientist MIT Media Laboratory A A Thesis Advisor Accepted by Ab Andrew B.Lippman Chairperson Departmental Committee on Graduate Students ROTCH MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 2 7 2002 LIBRARIES Developing a Framework for a Minority Language-based Utility by Marco Antonio Monroy Fonseca The following people served as readers for this thesis Reader Manuel Gendara Research Coordinator Centro de Cultura Digital Inttelmex Reader David Cavallo Principal Research Associate Future of Learning Group MIT Media Lab Developing a Framework for a Minority Language-based Utility by Marco Antonio Monroy Fonseca Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MEDIA TECHNOLOGY AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2002 Abstract While several efforts have been carried out for connecting ethnic groups to the Internet, few of them have been executed in developing countries, where lack of connectivity infrastructure prevents access of indigenous groups online, creating a less diverse World Wide Web where only few languages are present. -

Introduction

Introduction Since 1994, the Stabilizing Indigenous Languages Symposia/Conferences have provided an unparalleled opportunity for practitioners and scholars dedi- cated to supporting and developing the endangered indigenous languages of the world, particularly those of North America, to meet and share knowledge and experiences gained from research and community based practice. Established through leadership at Northern Arizona University and carried on through the voluntary efforts of academics and universities which have hosted the meetings since 1994, this symposium regularly consists of plenary addresses by leading Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal scholars, academic papers on field based experi- ence, and papers and workshops by Aboriginal academics and practitioners on initiatives in their communities to save and advance their languages. The meet- ings have been held in Flagstaff Arizona, Anchorage Alaska, Louisville Ken- tucky, and Tucson Arizona. The proceedings in this volume are papers from the seventh conference, held in Toronto in May of 2000. Proceedings were pub- lished in one volume for the first two symposia, then one each for the Fourth and Fifth. One essential feature of these conferences is that they have created a forum in which Aboriginal people involved with work on their own languages feel comfortable about coming together with academics from this field to discuss issues common to them both. In the past, well more than half of the attendees of this symposium have been Aboriginal people, mostly from the United States and Canada, but also including those from New Zealand, Australia, the South Pacific, Mexico, and Europe. At the Toronto conference, there were participants as well from Zimbabwe, North Atlantic countries, Russia, and Brazil. -

Canadian Indigenous Books for Schools Catalogue

indigenous indigenous indigenous indigenous FROM THE ASSOCIATION OF BOOK PUBLISHERS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Indigenous nous indigenous 2017•2018 indigenous indigenous indigenous selected and evaluated by teacher-librarians and evaluated selected indigenous books for schools Canadian Proud to support The Association of Book Publishers of British Columbia and the Canadian Indigenous Books for Schools catalogue ULS stocks and sources a wide variety of books and provides valuable essential services: First Nations Métis Inuit books BC curriculum supported books ULS Best New Books – For Children and Young Adults Young Readers’ Choice Award Nominees Reading and Writing Power School classroom starter collections Library opening day collections Levelled reading books Quality French materials Custom, in-house cataloguing Our Burnaby, BC facility and processing available offers the majority of these titles at a 25% discount and much more! 101B - 3430 Brighton Ave. HOURS Burnaby, BC V5A 3H4 SEPTEMBER TO JUNE JULY TO AUGUST phone: 604–421–1154 / 1–877–853–1200 Monday to Thursday: Monday to Thursday: fax: 604–421–2216 / 1–800–421–2216 8:15 am - 5:00pm 7:30 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. email: [email protected] Friday: 8:30am - 4:00pm Friday: 8:00 a.m. - 12:00 p.m Visit us online www.uls.com Dear librarians and educators, ordering First, a warm welcome to the library professionals who may be seeing this resource for information the first time. The Association of Book Publishers of British Columbia (ABPBC) represents the publish- Proud to support ing industry through cultural, economic, and political initiatives and engages book-related The Association of Book communities in British Columbia, Canada, and beyond. -

Indigenous Language Revitalization Efforts in Canada During COVID-19: Facilitating and Maintaining Connections Using Digital Technologies

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-29-2021 10:30 AM Indigenous Language Revitalization Efforts in Canada during COVID-19: Facilitating and Maintaining Connections using Digital Technologies Laura Gallant, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Granadillo de Espanol, Tania, The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Arts degree in Anthropology © Laura Gallant 2021 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Linguistic Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Gallant, Laura, "Indigenous Language Revitalization Efforts in Canada during COVID-19: Facilitating and Maintaining Connections using Digital Technologies" (2021). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7934. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7934 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This thesis explores how people involved in Indigenous language revitalization efforts in Canada have responded and adapted to the constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic from March to November 2020. Through virtual interviews, an online survey, an analysis of tweets about Indigenous language revitalization in Canada, and observations of webinars among people involved in language work, this research focuses on how people have adjusted and accelerated their Indigenous language activities during a prolonged period of social isolation. Genocidal policies and practices continue to reproduce inequities for Indigenous Peoples and are affecting those involved in Indigenous language work during COVID. -

Excavating Feminist Phenomenology: Lived-Experiences and Wellbeing of Indigenous Students at Western University

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-27-2019 12:00 PM Excavating Feminist Phenomenology: Lived-Experiences and Wellbeing of Indigenous Students at Western University Eva Lynn Cupchik The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Regna Darnell The University of Western Ontario Helen Fielding The University of Western Ontario Janice Forsyth The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Eva Lynn Cupchik 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Feminist Philosophy Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Cupchik, Eva Lynn, "Excavating Feminist Phenomenology: Lived-Experiences and Wellbeing of Indigenous Students at Western University" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6556. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6556 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Excavating Feminist Phenomenology: Lived-Experiences and Wellbeing of Indigenous Students at Western University Abstract The Truth and Reconciliation Commission underscores the need to incorporate narrative accounts of Indigenous students’ experiences as part of wide-scale de-colonizing efforts. This dissertation asks: how do Indigenous students experience their identities at Western University? What is at stake for phenomenology, feminist methods, and Indigenous theory in the post Truth and Reconciliation era? There is a gap between theories centering on reflective cognition in philosophy and the embodiment of land prevalent across Indigenous cultures. -

3.6 Cultural Resources

Section 3 Affected Environment 3.6 Cultural Resources 3.6.1 Introduction This section identifies cultural resources, which include archaeological resources and historic architectural resources located in the Study Area, and the prehistoric and historic contexts in which to place the cultural resources, and assesses the potential effects of the Proposed Action on these resources. The Study Area comprises the Area of Potential Effect (APE) for the Proposed Action and 1,000 feet of the APE; the APE for this analysis is defined as the 243 parcels (440 tax lots). In addition to determining the potential effects of the Proposed Action on identified cultural resources, the objectives of this analysis was be to demonstrate the long history of the Oneida within the Central New York Region and in particular, the parcels owned by the Nation that are subject of the trust transfer to the U.S. government; that the Oneida occupation and utilization of the Central New York Region is part of an even longer term utilization of this area by prior Native American cultures; and the importance of the Study Area (inclusive of the lands now owned by the Nation) to Oneida heritage, tradition, and identity both spiritually and in terms of developed lifeways. The Oneida homeland extends across present-day Oneida and Madison Counties in the Central New York Region, stretching from the upper Mohawk valley to the Oneida River drainage basin and includes the 17,370 acres of land now owned by the Nation and proposed for trust transfer. At its greatest historic extent, Nation lands extended from the Saint Lawrence River to the upper Susquehanna valley and beyond, a domain of about six million acres. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Karin Michelson University:Department of Linguistics Home: 2 Elm Court University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260 Snyder, NY 14226 716-645-2463 716-645-4956 [email protected] EDUCATION 1983 Ph.D. Linguistics, Harvard University. Dissertation: A Comparative Study of Accent in the Five Nations Iroquoian Language. 1975 B.A. First Class Joint Honours in Linguistics and Russian, McGill University. Thesis: Mohawk Aspect Suffixes. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 1979-82 Research Director, Centre for the Research and Teaching of Canadian Native Languages, and Lecturer in Anthropology, University of Western Ontario. 1982-83 Instructor, Linguistics, Harvard University. 1983-88 Assistant Professor, Linguistics, Harvard University. 1988-89 Associate Professor, Linguistics, Harvard University. 1989-90 Instructor, Native Language Teacher Training program (summer programs), University of Western Ontario and Lakehead University. 1989-2003 Associate Professor, Linguistics, University at Buffalo. 2003- Professor, Linguistics, University at Buffalo. 2011 Instructor/Professor, LSA Linguistic Institute 2011 (Language in the World), Hosted by the University of Colorado at Boulder. (July 7-August 2) AWARDS 2017 Exceptional Scholars Award for Sustained Achievement, University at Buffalo. 2018 Recognition by the Oneida of the Thames for linguistic service, Oneida Language Workshop, June 4. PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS Linguistics Society of America The Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES Editorial board Associate Editor, International Journal of American Linguistics, 2002-2005. 2 Conferences/Workshops Co-organizer (Christian DiCanio, organizer), Tonal Aspects of Language, 5th International Symposium, University at Buffalo, May 2016. Organizer, Annual Workshop for Teachers of Iroquoian Languages, University of Western Ontario, 1979-82. Organizer (with Michael K.