Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release for Spoken Here Published by Houghton Mifflin

Press Release Spoken Here by Mark Abley • Introduction • A Conversation with Mark Abley • Glossary of Threatened Languages • Praise for Spoken Here Introduction Languages are beautiful, astoundingly complex, living things. And like the many animals in danger of extinction, languages can be threatened when they lack the room to stretch and grow. In fact, of the six thousand languages in the world today, only six hundred may survive the next century. In Spoken Here, journalist Mark Abley takes us on a world tour — from the Arctic Circle to the outback of Australia — to track obscure languages and reveal their beauty and the devotion of those who work to save them. Abley is passionate about two things: traveling to remote places and seeking out rarities in danger of being lost. He combines his two passions in Spoken Here. At the age of forty-five, he left the security of home and job to embark on a quixotic quest to track language gems before they disappear completely. On his travels, Abley gives us glimpses of fascinating people and their languages: • one of the last two speakers of an Australian language, whose tribal taboos forbid him to talk to the other • people who believe that violence is the only way to save a tongue • a Yiddish novelist who writes for an audience that may not exist • the Amazonian language last spoken by a parrot • the Caucasian language with no vowels • a South Asian language whose innumerable verbs include gobray (to fall into a well unknowingly) and onsra (to love for the last time). Abley also highlights languages that can be found closer to home: Yiddish in Brooklyn and Montreal, Yuchi in Oklahoma, and Mohawk in New York and Quebec. -

Kanien'keha / Mohawk Indigenous Language

Kanien’keha / Mohawk Indigenous Language Revitalisation Efforts KANIEN’KEHA / MOHAWK INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE REVITALISATION EFFORTS IN CANADA GRACE A. GOMASHIE University of Western Ontario ABSTRACT. This paper gives an overview of ongoing revitalisation efforts for Kanien’keha / Mohawk, one of the endangered Indigenous languages in Canada. For the Mohawk people, their language represents a significant part of the culture, identity and well-being of individuals, families, and communities. The endanger- ment of Kanien’keha and other Indigenous languages in Canada was greatly accelerated by the residential school system. This paper describes the challenges surrounding language revitalisation in Mohawk communities within Canada as well as progress made, specifically for the Kanien’keha / Mohawk language. EFFORTS DE REVITALISATION LINGUISTIQUE DE LA LANGUE MOHAWK / KANIEN’KEHA AU CANADA RÉSUMÉ. Cet article offre une vue d’ensemble des efforts de revitalisation linguis- tique réalisés pour préserver la langue mohawk / kanien’keha, une des langues autochtones les plus menacées au Canada. Pour la communauté mohawk, cette langue constitue une part fondamentale de la culture, de l’identité et du bien-être des individus, des familles et des communautés. La mise en péril de la langue mohawk / kanien’keha et des autres langues autochtones au Canada a été grandement accentuée par le système de pensionnats autochtones. Cet article explore les défis inhérents à la revitalisation de la langue en cours dans les communautés mohawks au Canada et les progrès réalisés, particulièrement en ce qui a trait à la langue mohawk / kanien’keha. WHY SAVING ENDANGERED LANGUAGES IS IMPORTANT Linguists estimate that at least half of the world’s 7,000 languages will be endangered in a few generations as they are no longer being spoken as first languages (Austin & Sallabank, 2011; Krauss, 1992). -

Oneida Cultural Heritage Department Saving Our Oneida Language

Oneida Cultural Heritage Department By: Dr. Carol Cornelius and Judith L. Jourdan Edit, Revision, and Layout: Tiffany Schultz (09/13) Saving Our Oneida Language INTRODUCTION • All Oneida nation governmental By: Dr. Carol Cornelius meetings to conduct the business of the The Oneida Language Revitalization people were in Oneida Program began in the spring of 1996 in 1600’s response to a national crisis, a state of • The arrival of the French, Dutch, and emergency, in which a survey indicated there English began to impact our economy were only 25-30 Elders left who had learned to and these European languages were speak Oneida as their first language. learned by a few Oneida people in When many of us were very young, we order to conduct trade. heard Oneida spoken all the time by our Elders. 1700’s We must ensure that our little ones now hear • 1709 – Queen Anne ordered that the and learn to speak Oneida. As a Nation we have Common Prayer Book be translated into an urgent need to produce speakers to continue the Mohawk language. This was done Oneida Language. by Eleazer Williams in 1800. As a result of the survey taken, a ten • 1750 – Samuel Kirkland began year plan was developed to connect Elders with missionary efforts which impacted our trainees in a semi-immersion process which language. Many Oneida supported the would produce speakers and teachers of the Americans in the American Revolution. Oneida language. The goal was to hear our 1820’s Oneida language spoken throughout our • Eleazor William’s land negotiations and community. -

Sahuhlúkhane' Ukwehuwenéha They Learned to Speak It Again

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-10-2018 10:00 AM Sahuhlukhané ’ Ukwehuwenehá They Learned to Speak it Again: An Investigation into the Regeneration of the Oneida Language Rebecca Doxtator The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Debassige, Brent The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Education A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Rebecca Doxtator 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Indigenous Education Commons, Language and Literacy Education Commons, and the Language Description and Documentation Commons Recommended Citation Doxtator, Rebecca, "Sahuhlukhané ’ Ukwehuwenehá They Learned to Speak it Again: An Investigation into the Regeneration of the Oneida Language" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5766. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5766 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This study investigated the significance of the Oneida language to two groups of Oneida speakers and learners in the Onʌyota’á:ka’ Oneida Nation of the Thames community. This study included three research questions: (a) what is the significance of Oneida language to Oneida adult language learners who are seeking to acquire -

Language Teaching and Learning Software For

Natural Language Generation for Polysynthetic Languages: Language Teaching and Learning Software for Kanyen’keha´ (Mohawk) Greg Lessard Nathan Brinklow Michael Levison School of Computing Department of Languages, School of Computing Queen’s University Literatures and Cultures Queen’s University Canada Queen’s University Canada [email protected] Canada [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Kanyen’keha´ (in English, Mohawk) is an Iroquoian language spoken primarily in Eastern Canada (Ontario, Quebec).´ Classified as endangered, it has only a small number of speakers and very few younger native speakers. Consequently, teachers and courses, teaching materials and software are urgently needed. In the case of software, the polysynthetic nature of Kanyen’keha´ means that the number of possible combinations grows exponentially and soon surpasses attempts to capture variant forms by hand. It is in this context that we describe an attempt to produce language teaching materials based on a generative approach. A natural language generation environment (ivi/Vinci) embedded in a web environment (VinciLingua) makes it possible to produce, by rule, variant forms of indefinite complexity. These may be used as models to explore, or as materials to which learners respond. Generated materials may take the form of written text, oral utterances, or images; responses may be typed on a keyboard, gestural (using a mouse) or, to a limited extent, oral. The software also provides complex orthographic, morphological and syntactic analysis of learner productions. We describe the trajectory of development of materials for a suite of four courses on Kanyen’keha,´ the first of which will be taught in the fall of 2018. -

The Way of the Drum—When Earth Becomes Heart Part I

The Way of the Drum—When Earth Becomes Heart Part I Healing the Tears of Yesterday by the Drum Today: The Oneida Language is a Healing Medicine Grafton Antone As I travelled the path of life, little did I realize the suppression I was experiencing as an Ukwehuwe in my Euro-western formal educational journey. The Western model of human development is linear and has four general domains: emotional, social, physical, and intellectual. This Western model emphasizes physical and intellectual development to meet career standards and personal expectations. The Aboriginal Ukwehuwe model of human development is circular and consists of four parts: emotional, mental, physical, and spiritual. The Elders tell us that, to be fully developed, one must maintain balance in all four of these areas. My story shows my development in the Western model. My perseverance afforded me a certain measure of success, but as I passed through the different stages of life, I could sense that there was something missing in my life that I could not explain or identify. It was not until I began teaching the Oneida Language (Onyota’a:ka) that I realized what the missing links were. This is my story of discovery, reorientation, and balance. The information I will share with you is based on my work with various adult students learning Onyota’a:ka as a Second Language in the Toronto School Board. In 1995-96, the class had a high enrolment of 30, but that gradually fell off to about 15. In 1996-97, the class began at 22 then tapered off to 10. -

The Experiences of Post-Secondary Cree Language

Islands ofCulture: The experiences ofpost-secondary Cree language teachers A Thesis Submitted to the College ofGraduate Studies and Research for the Degree ofMaster ofEducation in the Department ofCurriculum Studies University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon By Velma Baptiste Willett . Saskatoon, Saskatchewan 2000 Copyright Velma Baptiste Willett, Fall 2000, All rights reserved I agree that the Libraries ofthe University ofSaskatchewan may make this thesis freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying ofthis thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised the thesis work recorded herein, or, in their absence, by the Head ofthe Department ofDean ofthe College in which the thesis work was done. Any copying or publication or use ofthis thesis or parts thereoffor financial gain is not allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition will be given to me and to the University ofSaskatchewan in any scholarly use ofthe material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use ofmaterial in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head ofthe Department ofCurriculum Studies University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N OXI ABSTRACT This study recognizes that post-secondary Cree language teachers carry expertise in providing relevant teaching strategies for adult learners. Pursuant to this perspective~ this study describes current Cree language teaching approaches for adult learners as practiced by selected post-secondary Cree language teachers. The Cree language teachers interviewed in this qualitative study are fluent Cree speakers who possess traditional Cree knowledge and understand the protocol within Cree communities. -

A Typology of Stress- and Foot-Sensitive Consonantal Phenomena1

A Typology of Stress- and Foot-Sensitive Consonantal Phenomena1 Carolina González Florida State University DOI: https://doi.org/10.1387/asju.18680 Abstract This article investigates consonantal alternations that are conditioned by stress and/ or foot-structure. A survey of 78 languages from 37 language families reveals three types of consonantal phenomena: (i) those strictly motivated by stress (as in Senoufo lengthen- ing), (ii) those exclusively conditioned by foot structure (as in /h/ epenthesis in Huariapano), and (iii) those motivated both by stress and foot structure (as in flapping in American Eng- lish). The fact that stress-only and foot-only consonantal phenomena are attested alongside stress/foot structure conditioned phenomena leads to the proposal that stress and foot struc- ture can work independently, contradicting the traditional view of foot structure organiza- tion as signaled by stress-based prominence. It is proposed that four main factors are at play in the consonantal phenomena under investigation: perception, duration, aerodynamics, and prominence. Duration, aerodynamics and perceptual ambiguity are primarily phonetic, while prominence and other perceptual factors are primarily phonological. It is shown that the mechanism of Prominence Alignment in Optimality Theory captures not only consonan- tal alternations based on prominence, but can also be extended to those with durational and aerodynamic bases. This article also makes predictions regarding unattested stress/foot sensi- tive alternations connected to the four factors mentioned above. Keywords: stress; foot structure; consonantal alternations; phonological typology; percep- tion; duration; aerodynamics; prominence; Prominence Alignment; Optimality Theory. 1 This is a revised version of chapters 1-3 and 6 of my Ph.D. -

THIS LAND a COMPANION RESOURCE for EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS 1: Welcome

ThisA Companion Resource forLand Early Childhood Educators to Accompany Five Short Films To you, the Early Childhood Educators, embarking on this emotional journey Thank you for taking this on. Some days it may seem insurmountable to both learn about and feel the painful history of this country in its treatment of Indigenous Peoples. We are grateful for the gentle, important work you do in caring for young children. They are the now and the future. 2 THIS LAND A COMPANION RESOURCE FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS 1: Welcome si:y̓em̓ nə siyey̓ə My honoured friends and relatives. c̓iyətalə cən tə ɬwələp xʷəʔiʔnamət ʔə ƛ̓ xʷməθkʷəy̓əm I thank you all for coming to Musqueam. stəʔe k̓ʷ nə syəwenəɬ qiyəplenəxʷ ʔiʔ xʷəlciməltxʷ Like my ancestors qiyəplenəxʷ and xʷəlciməltxʷ seʔcsəm cən niʔ ʔə tə ɬwələp ʔiʔ hiləkʷstalə I raise my hands to welcome all of you. hay ce:p ʔewəɬ si:y̓em̓ nə siyey̓ə Thank you, all my friends and relatives, wə n̓an ʔəw ʔəy̓ tə nə šxʷqʷeləwən kʷəns ʔi k̓ʷəcnalə ʔə šxʷə ʔi ʔə tə ʔi I’m very happy to see you all here. hay čxʷ q̓ə Thank you. 2 THIS LAND A COMPANION RESOURCE FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS THIS LAND A COMPANION RESOURCE FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS 3 First Nations Tutchone Languages of Den k’e Inland Łingít British Columbia © 2011 UBC Museum of Anthropology This map is regularly revised. Latest revision November 24,2011. Please do not reproduce in any form without permission. First Nations languages are shown with outlines that are approximate represent- Language ations of their geographic locations. -

ED436973.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 436 973 FL 026 097 AUTHOR Martin, Joyce, Comp. TITLE Native American Languages: Subject Guide. INSTITUTION Arizona State Univ., Tempe. Univ. Library. PUB DATE 1999-08-00 NOTE 12p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: <http://www.asu.edu/lib/archives/labriola.htm> and <http://www.asu.edu/lib/archives/labriola.htm>. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Languages; Biblical Literature; Bilingual Education; Dictionaries; English (Second Language); Indigenous Populations; *Library Guides; Sign Language; Tape Recordings; Uncommonly Taught Languages IDENTIFIERS *Native Americans ABSTRACT This document is an eleven-page supplemental subject guide listing reference material that focuses on Native American languages that is not available in the Labriola National American Indian Data Center in the Arizona State University, Tempe (ASU) libraries. The guide is not comprehensive but offers a selective list of resources useful for developing language and vocabulary skills or researching a variety of topics dealing with native North American languages. Additional material may be found using the ASU online catalogue and the Arizona Southwest index. Contents include: bibles and hymnals; bibliographies; bilingual education, curriculum, and workbooks; culture, history, and language; dictionaries and grammar books; English as a Second Language; guides and handbooks; language tapes; linguistics; online access; sign language.(KFT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Native American Languages Subject Guide The following bibliography lists reference material dealing with Native American languages which is available in the Labriola National American Indian Data Center in the University Libraries. It is not comprehensive, but rather a selective list of resources useful for developing language and vocabulary skills, and/or researching a variety of topics dealing with Native North American languages. -

Linguistic Theory, Collaborative Language Documentation, and the Production of Pedagogical Materials

Introduction: Collaborative approaches to the challenges of language documentation and conservation edited by Wilson de Lima Silva Katherine J. Riestenberg Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 20 PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai'i 96822 USA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu Hawai'i 96822 1888 USA © All texts and images are copyright to the respective authors, 2020 All chapters are licensed under Creative Commons Licenses Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International Cover designed by Katherine J. Riestenberg Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN-13: 978-0-9973295-8-2 http://hdl.handle.net/24939 ii Contents Contributors iv 1. Introduction: Collaborative approaches to the challenges of language 1 documentation and conservation Wilson de Lima Silva and Katherine J. Riestenberg 2. Integrating collaboration into the classroom: Connecting community 6 service learning to language documentation training Kathryn Carreau, Melissa Dane, Kat Klassen, Joanne Mitchell, and Christopher Cox 3. Indigenous universities and language reclamation: Lessons in balancing 20 Linguistics, L2 teaching, and language frameworks from Blue Quills University Josh Holden 4. “Data is Nice:” Theoretical and pedagogical implications of an Eastern 38 Cherokee corpus Benjamin Frey 5. The Kawaiwete pedagogical grammar: Linguistic theory, collaborative 54 language documentation, and the production of pedagogical materials Suzi Lima 6. Supporting rich and meaningful interaction in language teaching for 73 revitalization: Lessons from Macuiltianguis Zapotec Katherine J. Riestenberg 7. The Online Terminology Forum for East Cree and Innu: A collaborative 89 approach to multi-format terminology development Laurel Anne Hasler, Marie Odile Junker, Marguerite MacKenzie, Mimie Neacappo, and Delasie Torkornoo 8. -

Speech Acts Conference Program 3.Indd

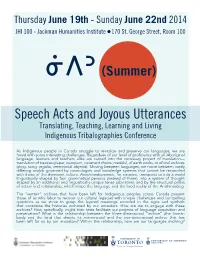

Thursday June 19th - Sunday June 22nd 2014 JHI 100 - Jackman Humanities Institute 170 St. George Street, Room 100 ᓃᐱᐣ (Summer) Speech Acts and Joyous Utterances Translating, Teaching, Learning and Living Indigenous Tribalographies Conference As Indigenous people in Canada struggle to revitalize and preserve our languages, we are faced with some interesting challenges. Regardless of our level of proficiency with an Aboriginal language, learners and teachers alike are carried into the necessary project of translation— translation of treaties (paper, wampum, covenant chains, medals), of earth works, or of oral archives (story, song, regalia, ceremonial objects). Moving between languages, we move between vastly differing worlds governed by cosmologies and knowledge systems that cannot be reconciled with those of the dominant culture. Aniishinaabemowin, for instance, transports us into a world linguistically shaped by four grammatical persons (instead of three), into a system of thought shaped by an additional and linguistically unique tense (obviative), and by the structural pillars of action and relationship, which shape the language and the lived reality of the Anishinaabeg. The “written” archives that have been left for Indigenous peoples across Canada present those of us who labor to recover our cultural legacies with unique challenges and compelling questions as we strive to grasp the layered meanings encoded in the signs and symbols that constitute the histories authored by our ancestors. How are we to engage with these archives? How,