Elizabeth Bay House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

07 July 1980, No 3

AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER 1980/3 July 1980 •• • • • •• • •••: •.:• THE AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER ISSN 0156.8019 The Australiana Society P.O. Box A 378 Sydney South NSW 2000 1980/3, July 1980 SOCIETY INFORMATION p. k NOTES AND NEWS P-5 EXHIBITIONS P.7 ARTICLES - John Wade: James Cunningham, Sydney Woodcarver p.10 James Broadbent: The Mint and Hyde Park Barracks P.15 Kevin Fahy: Who was Australia's First Silversmith p.20 Ian Rumsey: A Guide to the Later Works of William Kerr and J. M. Wendt p.22 John Wade: Birds in a Basket p.24 NEW BOOKS P.25 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS p.14 OUR CONTRIBUTORS p.28 MEMBERSHIP FORM P.30 Registered for posting as a publication - category B Copyright C 1980 The Australiana Society. All material written or illustrative, credited to an author, is copyright. pfwdaction - aJLbmvt Kzmkaw (02) 816 U46 it Society information NEXT MEETING The next meeting of the Society will be at the Kirribilli Neighbourhood Centre, 16 Fitzroy Street, Kirribilli, at 7-30 pm on Thursday, 7th August, 1980. This will be the Annual General Meeting of the Society when all positions will be declared vacant and new office bearers elected. The positions are President, two Vice-Presidents, Secretary, Treasurer, Editor, and two Committee Members. Nominations will be accepted on the night. The Annual General Meeting will be followed by an AUCTION SALE. All vendors are asked to get there early to ensure that items can be catalogued and be available for inspection by all present. Refreshments will be available at a moderate cost. -

Harbour Bridge to South Head and Clovelly

To NEWCASTLE BARRENJOEY A Harbour and Coastal Walk Personal Care This magnificent walk follows the south-east shoreline of Sydney Harbour The walk requires average fitness. Take care as it includes a variety of before turning southwards along ocean beaches and cliffs. It is part of one pathway conditions and terrain including hills and steps. Use sunscreen, of the great urban coast walks of the world, connecting Broken Bay in carry water and wear a hat and good walking shoes. Please observe official SYDNEY HARBOUR Sydney's north to Port Hacking to its south (see Trunk Route diagram), safety and track signs at all times. traversing the rugged headlands and sweeping beaches, bush, lagoons, bays, and harbours of coastal Sydney. Public Transport The walk covered in this map begins at the Circular Quay connection with Public transport is readily available at regular points along the way Harbour Bridge the Harbour Circle Walk and runs to just past coastal Bronte where it joins (see map). This allows considerable flexibility in entering and exiting the Approximate Walking Times in Hours and Minutes another of the series of maps covering this great coastal and harbour route. routes. Note - not all services operate every day. to South Head e.g. 1 hour 45 minutes = 1hr 45 The main 29 km Harbour Bridge (B3) to South Head (H1) and to Clovelly Bus, train and ferry timetables. G8) walk (marked in red on the map) is mostly easy but fascinating walk- Infoline Tel: 131-500 www.131500.com.au 0 8 ing. Cutting a 7km diagonal across the route between Rushcutters Bay (C5) and Clovelly kilometres and Clovelly, is part of the Federation Track (also marked in red) which, in Short Walks using Public Transport Brochure 1 To Manly NARRABEEN full, runs from Queensland to South Australia. -

The Story of Barncleuth (Later Kinneil)

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND VOL. 33 Edited by AnnMarie Brennan and Philip Goad Published in Melbourne, Australia, by SAHANZ, 2016 ISBN: 978-0-7340-5265-0 The bibliographic citation for this paper is: Judith O’Callaghan “Trophy House: The Story of Barncleuth (later Kinneil).” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 33, Gold, edited by AnnMarie Brennan and Philip Goad, 538-549. Melbourne: SAHANZ, 2016. All efforts have been undertaken to ensure that authors have secured appropriate permissions to reproduce the images illustrating individual contributions. Interested parties may contact the editors. Judith O’Callaghan UNSW Australia TROPHY HOUSE: THE STORY OF BARNCLEUTH (LATER KINNEIL) Kinneil was a rare domestic commission undertaken by the prominent, and often controversial architect, J. J. Clark. Though given little prominence in recent assessments of Clark’s oeuvre, plans and drawings of “Kinneil House,” Elizabeth Bay Road, Sydney, were published as a slim volume in 1891. The arcaded Italianate villa represented was in fact a substantial remodelling of an earlier house on the site, Barncleuth. Built by James Hume for wine merchant John Brown, it had been one of the first of the “city mansions” to be erected on the recently subdivided Macleay Estate in 1852. Brown was a colonial success story and Barncleuth was to be both his crowning glory and parting gesture. Within only two years of the house’s completion he was on his way back to Britain to spend the fortune he had amassed in Sydney. Over the following decades, Barncleuth continued to represent the golden prize for the socially mobile. -

14 April 1982, No 2

THE AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER 1982/2 APRIL, 1982 Registered by Australia Post Publication No. NBH 2771 THE AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER ISSN 0156.8019 Published by: The Australiana Society 1982/1 Box A 378 April, 1982 Sydney South NSW 2000 EDITORIAL SOCIETY INFORMATION AUSTRALIANA NEWS ARTICLES - Ian Rumsey - The Case of the Oatley Clock: Is There a Case to Answer p. 9 David Dolan - Sydney's Colonial Craftsmen at Elizabeth Bay House p.10 Kai Romot - The Sydney Technical College and Its Architect, W E Kemp. p.12 Ian G Sanker - Richard Daintree, A Note on His Photographs p.16 Juliet Cook - Sydney Harbour Bridge 50th Anniversary p.16 AUSTRALIANA BOOKS p.18 BOOK REVIEWS p.20 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS p.15 OUR AUTHORS p. 20 MEMBERSHIP FORM p.21 All editorial correspondence should be addressed to John Wade, Editor, Australiana Society Newslatter, c/- Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. 659 Harris Street, Ultimo, NSW, 2007. Copyright 1982 The Australiana Society. All material written or illustrative, credited to an author, photographer, draftsman, or artist, is copyright. We gratefully record our thanks to James R Lawson Pty Ltd for their generous donation towards the cost of illustrations. 4 Editorial The quality of this newsletter has little to do with its Editor. It depends much more on the articles and news items which you submit. Fortunately your Editor has a thick hide and a large stick with which to bludgeon those unfortunate enough to get near him, into writing articles. But with travel now restricted by Government cutbacks, we are very much becoming limited to Sydney news and Sydney articles. -

Environment Committee

Significant Tree Listings 21. Darlinghurst © City of Sydney Register of Significant Trees 2013 - Draft for Council Adoption (May 2013) C-124 Significant Tree Listings 21.01 Green Park Address: Historical Notes Darlinghurst Road, Burton Street and Victoria Street, Green Park has high local significance as a rare public open Darlinghurst space in Darlinghurst which was dedicated in 1875. It is an Ownership Type: important townscape feature. The octagonal bandstand (1925), Park and the two memorials, the Gay and Lesbian Holocaust Memorial Owner/ Controlling Authority: (2001) which commemorates gay men and women who lost their City of Sydney lives during World War II, and the memorial to Victor Chang Year of planting (of oldest item / if known) containing a canopied drinking fountain, are important elements c. 1880 within the park. The park was named after Alderman James Green who represented the district from 1869 to 1883. Scheduled Significant Trees The Green Park Group (including the bandstand pavilion, Qty Species Common Name perimeter fence and landscaping) is scheduled in the City of 8 Ficus macrophylla Moreton Bay Fig Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012, Sydney City Heritage Study and classified by the National Trust of Australia (NSW). 5 Washingtonia robusta Washington Palm The park also adjoins the ‘Victoria Streetscape Area’, an area of high streetscape value scheduled in the LEP. The park is considered to be significant as an integral component of this historic precinct. Description The Park is a rectangular-shaped parcel of public land in the centre of Darlinghurst, is bounded by Darlinghurst Road (west), Burton Street north), Victoria Street (east) and The Sacred Heart Palliative Care & Rehabilitation Centre (south). -

'Quilled on the Cann': Alexander Hart, Scottish Cabinet Maker, Radical

‘QUILLED ON THE CANN’ ALEXANDER HART, SCOTTISH CABINET MAKER, RADICAL AND CONVICT John Hawkins A British Government at war with Revolutionary and Republican France was fully aware of the dangers of civil unrest amongst the working classes in Scotland for Thomas Paine’s Republican tract The Rights of Man was widely read by a particularly literate artisan class. The convict settlement at Botany Bay had already been the recipient of three ‘Scottish martyrs’, the Reverend Thomas Palmer, William Skirving and Thomas Muir, tried in 1793 for seeking an independent Scottish republic or democracy, thereby forcing the Scottish Radical movement underground. The onset of the Industrial Revolution, and the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars placed the Scottish weavers, the so called ‘aristocrats’ of labour, in a difficult position for as demand for cloth slumped their wages plummeted. As a result, the year 1819 saw a series of Radical protest meetings in west and central Scotland, where many thousands obeyed the order for a general strike, the first incidence of mass industrial action in Britain. The British Government employed spies to infiltrate these organisations, and British troops were aware of a Radical armed uprising under Andrew Hardie, a Glasgow weaver, who led a group of twenty five Radicals armed with pikes in the direction of the Carron ironworks, in the hope of gaining converts and more powerful weapons. They were joined at Condorrat by another group under John Baird, also a weaver, only to be intercepted at Bonnemuir, where after a fight twenty one Radicals were arrested and imprisoned in Stirling Castle. -

'Paper Houses'

‘Paper houses’ John Macarthur and the 30-year design process of Camden Park Volume 2: appendices Scott Ethan Hill A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Faculty of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney Sydney, Australia 10th August, 2016 (c) Scott Hill. All rights reserved Appendices 1 Bibliography 2 2 Catalogue of architectural drawings in the Mitchell Library 20 (Macarthur Papers) and the Camden Park archive Notes as to the contents of the papers, their dating, and a revised catalogue created for this dissertation. 3 A Macarthur design and building chronology: 1790 – 1835 146 4 A House in Turmoil: Just who slept where at Elizabeth Farm? 170 A resource document drawn from the primary sources 1826 – 1834 5 ‘Small town boy’: An expanded biographical study of the early 181 life and career of Henry Kitchen prior to his employment by John Macarthur. 6 The last will and testament of Henry Kitchen Snr, 1804 223 7 The last will and testament of Mary Kitchen, 1816 235 8 “Notwithstanding the bad times…”: An expanded biographical 242 study of Henry Cooper’s career after 1827, his departure from the colony and reported death. 9 The ledger of John Verge: 1830-1842: sections related to the 261 Macarthurs transcribed from the ledger held in the Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, A 3045. 1 1 Bibliography A ACKERMANN, JAMES (1990), The villa: form and ideology of country houses. London, Thames & Hudson. ADAMS, GEORGE (1803), Geometrical and Graphical Essays Containing a General Description of the of the mathematical instruments used in geometry, civil and military surveying, levelling, and perspective; the fourth edition, corrected and enlarged by William Jones, F. -

AH374 Australian Art and Architecture

AH374 Australian Art and Architecture The search for beauty, meaning and freedom in a harsh climate Boston University Sydney Centre Spring Semester 2015 Course Co-ordinator Peter Barnes [email protected] 0407 883 332 Course Description The course provides an introduction to the history of art and architectural practice in Australia. Australia is home to the world’s oldest continuing art tradition (indigenous Australian art) and one of the youngest national art traditions (encompassing Colonial art, modern art and the art of today). This rich and diverse history is full of fascinating characters and hard won aesthetic achievements. The lecture series is structured to introduce a number of key artists and their work, to place them in a historical context and to consider a range of themes (landscape, urbanism, abstraction, the noble savage, modernism, etc.) and issues (gender, power, freedom, identity, sexuality, autonomy, place etc.) prompted by the work. Course Format The course combines in-class lectures employing a variety of media with group discussions and a number of field trips. The aim is to provide students with a general understanding of a series of major achievements in Australian art and its social and geographic context. Students should also gain the skills and confidence to observe, describe and discuss works of art. Course Outline Week 1 Session 1 Introduction to Course Introduction to Topic a. Artists – The Port Jackson Painter, Joseph Lycett, Tommy McCrae, John Glover, Augustus Earle, Sydney Parkinson, Conrad Martens b. Readings – both readers are important short texts. It is compulsory to read them. They will be discussed in class and you will need to be prepared to contribute your thoughts and opinions. -

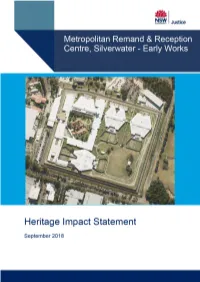

Silverwater Correctional Complex Upgrade Early Works

THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK Table of Contents Contents Heritage Impact Statement ........................................................................................................... 1 Document Control .................................................................................................................... 5 1. Project Overview ............................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 The Site ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.3 Heritage Context ................................................................................................................... 8 1.4 Silverwater Correctional Complex CMP ................................................................................ 8 2. History ............................................................................................................................ 10 3. Site and Building Descriptions ..................................................................................... 13 3.1 Context within the Site ........................................................................................................ 13 3.2 Current Use ........................................................................................................................ 13 4. Significance -

2004-2005 Annual Report

Historic Houses Trust Annual Report 04 > 05 | At a glance At a glance In this financial year 2004–05 we achieved what we set out to do and significantly advanced the goals and strategies of the organisation in our fourth year of reporting using our Corporate Plan 2001–06. Our standing educate without being didactic, to embrace cultural diversity and produce relevant and The Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales Acquired Property Opened contemporary programs which relate to a was established under the Historic Houses wide range of communities. We welcome Act 1980 to manage, conserve and interpret 1980 Vaucluse House 1980 everyone and do our best to provide services the properties vested in it, for the education that will attract all sectors of the community. 1980 Elizabeth Bay House 1980 and enjoyment of the public. We are a statutory authority of the state government of 1984 Elizabeth Farm 1984 New South Wales funded through the NSW Recognition 1984 Lyndhurst (sold 2005) Ministry for the Arts. We are one of the largest This year HHT projects won eight awards state museum bodies in Australia and a leader and four commendations: 1985 Meroogal 1988 in conservation and management of historic Awards 1987 Rouse Hill estate 1999 places in this country. We are guided by the • Royal Australian Institute of Architects NSW 1988 Rose Seidler House 1991 view that our museums must be part of Chapter Sir John Sulman Award for current debates in the community, open to Outstanding Public Architecture for The Mint 1990 Hyde Park Barracks Museum 1991 new ideas as much as they are the • Royal Australian Institute of Architects NSW 1990 Justice & Police Museum 1991 repositories of important collections and the Chapter Greenway Award for Conservation memories of the community. -

Drawing the Line Between Native and Stranger

DRAWING THE LINE BETWEEN NATIVE AND STRANGER Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of New South Wales for the degree of Master of Fine Arts by Research by Fiona Melanay MacDonald March 2010 ABSTRACT Drawing the Line between Native and Stranger Fiona MacDonald The Research Project Drawing the Line between Native and Stranger explores the repercussions of the foundational meeting at Botany Bay through a culture of protest and opposition. The project took form as sets of print works presented in an exhibition and thus the work contributes to the ongoing body of Art produced about the ways that this foundational meeting has shaped our culture. The Research Project is set out in three broad overlapping categories: Natives and Strangers indicated in the artwork by the use of Sydney Language and specific historic texts; Environment; the cultural clash over land use, and Continuing Contest — the cycle of exploitation and loss. These categories are also integrated within a Legend that details historical material that was used in the development of the key compositional elements of the print folio. The relationship between Native and Stranger resonates in the work of many Australian artists. To create a sense of the scope, range and depth of the dialogue between Native and Stranger, artists whose heritage informs their work were discussed to throw some light from their particular points of view. In conclusion, a document and suite of print-based work traces the interaction and transformation of both Native and Stranger -

Annual Report 2019–2020 Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales

Annual Report 2019–2020 Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales The Hon Don Harwin MLC Special Minister of State, and Minister for the Public Service and Employee Relations, Aboriginal Affairs, and the Arts Parliament House Macquarie Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Minister On behalf of the Board of Trustees and in accordance with the provisions of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984, the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983 and the Public Finance and Audit Regulation 2015, we submit for presentation to Parliament the Annual Report of Sydney Living Museums under the statutory authority of the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales for the year ending 30 June 2020. Yours sincerely Naseema Sparks am Adam Lindsay Chair Executive Director The Historic Houses Trust of NSW, incorporating Sydney Living Museums Sydney Living Museums, cares for significant Head Office historic places, buildings, landscapes and The Mint, 10 Macquarie Street collections. It is a statutory authority of, and Sydney NSW 2000 principally funded by, the NSW Government. T 02 8239 2288 E [email protected] This report is published on our website sydneylivingmuseums.com.au 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2019–20 Contents Acknowledgment of Country 4 Operational Plans 48 From the Chair 6 Placemaking, Curation & Collaboration 48 From the Executive Director 7 Public programs 50 Vision, mission, essence, values and approach 8 Learning programs 53 Highlights 2019–20 10 Exhibitions 54 Performance overview 12 Case study – A Thousand Words 58 Visitation 14 Touring exhibition program 61 Research