Universal Protein Families and the Functional Content of the Last Universal Common Ancestor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Part One Amino Acids As Building Blocks

Part One Amino Acids as Building Blocks Amino Acids, Peptides and Proteins in Organic Chemistry. Vol.3 – Building Blocks, Catalysis and Coupling Chemistry. Edited by Andrew B. Hughes Copyright Ó 2011 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim ISBN: 978-3-527-32102-5 j3 1 Amino Acid Biosynthesis Emily J. Parker and Andrew J. Pratt 1.1 Introduction The ribosomal synthesis of proteins utilizes a family of 20 a-amino acids that are universally coded by the translation machinery; in addition, two further a-amino acids, selenocysteine and pyrrolysine, are now believed to be incorporated into proteins via ribosomal synthesis in some organisms. More than 300 other amino acid residues have been identified in proteins, but most are of restricted distribution and produced via post-translational modification of the ubiquitous protein amino acids [1]. The ribosomally encoded a-amino acids described here ultimately derive from a-keto acids by a process corresponding to reductive amination. The most important biosynthetic distinction relates to whether appropriate carbon skeletons are pre-existing in basic metabolism or whether they have to be synthesized de novo and this division underpins the structure of this chapter. There are a small number of a-keto acids ubiquitously found in core metabolism, notably pyruvate (and a related 3-phosphoglycerate derivative from glycolysis), together with two components of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), oxaloacetate and a-ketoglutarate (a-KG). These building blocks ultimately provide the carbon skeletons for unbranched a-amino acids of three, four, and five carbons, respectively. a-Amino acids with shorter (glycine) or longer (lysine and pyrrolysine) straight chains are made by alternative pathways depending on the available raw materials. -

Mapping Active Site Residues in Glutamate-5-Kinase. the Substrate Glutamate and the Feed-Back Inhibitor Proline Bind at Overlapping Sites

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector FEBS Letters 580 (2006) 6247–6253 Mapping active site residues in glutamate-5-kinase. The substrate glutamate and the feed-back inhibitor proline bind at overlapping sites Isabel Pe´rez-Arellanoa, Vicente Rubiob, Javier Cerveraa,* a Centro de Investigacio´n Prı´ncipe Felipe, Avda. Autopista del Saler, 16, Valencia 46013, Spain b Instituto de Biomedicina de Valencia (IBV-CSIC), Jaime Roig 11, Valencia 46010, Spain Received 22 August 2006; revised 10 October 2006; accepted 12 October 2006 Available online 20 October 2006 Edited by Stuart Ferguson (a domain named after pseudo uridine synthases and archaeo- Abstract Glutamate-5-kinase (G5K) catalyzes the controlling first step of proline biosynthesis. Substrate binding, catalysis sine-specific transglycosylases) domain [10]. AAK domains and feed-back inhibition by proline are functions of the N-termi- bind ATP and a phosphorylatable acidic substrate, and make nal 260-residue domain of G5K. We study here the impact on a phosphoric anhydride [11]. The function of the PUA domain these functions of 14 site-directed mutations affecting 9 residues (a domain characteristically found in some RNA-modifying of Escherichia coli G5K, chosen on the basis of the structure of enzymes) [12] is not known. By deleting the PUA domain of the bisubstrate complex of the homologous enzyme acetylgluta- E. coli G5K we showed [10] that the isolated AAK domain, mate kinase (NAGK). The results support the predicted roles as the complete enzyme, forms tetramers, catalyzes the reac- of K10, K217 and T169 in catalysis and ATP binding and of tion and is feed-back inhibited by proline. -

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution Enhances Methanol Tolerance and Conversion in Engineered Corynebacterium Glutamicum

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-0954-9 OPEN Adaptive laboratory evolution enhances methanol tolerance and conversion in engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum Yu Wang 1, Liwen Fan1,2, Philibert Tuyishime1, Jiao Liu1, Kun Zhang1,3, Ning Gao1,3, Zhihui Zhang1,3, ✉ ✉ 1234567890():,; Xiaomeng Ni1, Jinhui Feng1, Qianqian Yuan1, Hongwu Ma1, Ping Zheng1,2,3 , Jibin Sun1,3 & Yanhe Ma1 Synthetic methylotrophy has recently been intensively studied to achieve methanol-based biomanufacturing of fuels and chemicals. However, attempts to engineer platform micro- organisms to utilize methanol mainly focus on enzyme and pathway engineering. Herein, we enhanced methanol bioconversion of synthetic methylotrophs by improving cellular tolerance to methanol. A previously engineered methanol-dependent Corynebacterium glutamicum is subjected to adaptive laboratory evolution with elevated methanol content. Unexpectedly, the evolved strain not only tolerates higher concentrations of methanol but also shows improved growth and methanol utilization. Transcriptome analysis suggests increased methanol con- centrations rebalance methylotrophic metabolism by down-regulating glycolysis and up- regulating amino acid biosynthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, ribosome biosynthesis, and parts of TCA cycle. Mutations in the O-acetyl-L-homoserine sulfhydrylase Cgl0653 catalyzing formation of L-methionine analog from methanol and methanol-induced membrane-bound transporter Cgl0833 are proven crucial for methanol tolerance. This study demonstrates the importance of -

Yeast Genome Gazetteer P35-65

gazetteer Metabolism 35 tRNA modification mitochondrial transport amino-acid metabolism other tRNA-transcription activities vesicular transport (Golgi network, etc.) nitrogen and sulphur metabolism mRNA synthesis peroxisomal transport nucleotide metabolism mRNA processing (splicing) vacuolar transport phosphate metabolism mRNA processing (5’-end, 3’-end processing extracellular transport carbohydrate metabolism and mRNA degradation) cellular import lipid, fatty-acid and sterol metabolism other mRNA-transcription activities other intracellular-transport activities biosynthesis of vitamins, cofactors and RNA transport prosthetic groups other transcription activities Cellular organization and biogenesis 54 ionic homeostasis organization and biogenesis of cell wall and Protein synthesis 48 plasma membrane Energy 40 ribosomal proteins organization and biogenesis of glycolysis translation (initiation,elongation and cytoskeleton gluconeogenesis termination) organization and biogenesis of endoplasmic pentose-phosphate pathway translational control reticulum and Golgi tricarboxylic-acid pathway tRNA synthetases organization and biogenesis of chromosome respiration other protein-synthesis activities structure fermentation mitochondrial organization and biogenesis metabolism of energy reserves (glycogen Protein destination 49 peroxisomal organization and biogenesis and trehalose) protein folding and stabilization endosomal organization and biogenesis other energy-generation activities protein targeting, sorting and translocation vacuolar and lysosomal -

Fig.S1 Real-Time PCR Analysis of Select Genes from Different Metabolic Pathways S. Cerevisiae Transformants Expressing TEF-YCT1

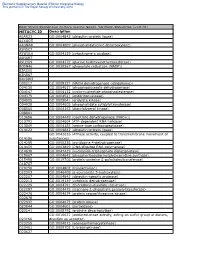

Fig.S1 Real-time PCR analysis of select genes from different metabolic pathways S. cerevisiae transformants expressing TEF-YCT1 were either exposed to 500µM cysteine or no cysteine for 5 hours (Control samples). Total RNA was extracted followed by cDNA synthesis. RT-PCR analysis was done using SYBR green dye-based method. The experiment was carried out twice and the figure represents expression levels of the above mentioned genes in treated samples relative to the corresponding untreated control samples. The data above are means ± SD from technical replicates (n=3) of the biological duplicates. [ARG8, ARG5,6 and RTC2 belong to the arginine biosynthetic pathway, SSU1 is a part of sulphur metabolism and TIS11 is a gene involved in maintaining iron homeostasis in the cells.] Table S1: List of strains used in this study Strain Genotype Source ABC 1738 (yct1) MATα his31 leu20 lys20 ura30 YLL055W:: kanMX4 Euroscarf (Y01543) ABC3612(arg3) MATa his31 leu20 ura30 YJL088w::kanMX4 Euroscarf (Y11335) ABC4812(arg5,6) MATa his31 leu20 ura30 YER069w::kanMX4 Euroscarf (Y10209) ABC4811(arg8) MATa his31 leu20 ura30 YOL140w::kanMX4 Euroscarf (Y17711) ABC4814(spe1) MATa his31 leu20 ura30 YKL184w::kanMX4 Euroscarf (Y15034) ABC4815(spe2) MATa his31 leu20 ura30 YOL052c::kanMX4 Euroscarf (Y11743) ABC4816(spe3) MATa his31 leu20 ura30 YPR069c::kanMX4 Euroscarf (Y15488) ABC4817(spe4) MATa his31 leu20 ura30 YLR146c::kanMX4 Euroscarf (Y16945) ABC3604(ssu1) MATa his31 leu20 ura30 YPL092w::kanMX4 Euroscarf (Y12160) ABC1486(str2) MATa his31 leu20 ura30 YJR130c::kanMX4 -

Table S1. List of Oligonucleotide Primers Used

Table S1. List of oligonucleotide primers used. Cla4 LF-5' GTAGGATCCGCTCTGTCAAGCCTCCGACC M629Arev CCTCCCTCCATGTACTCcgcGATGACCCAgAGCTCGTTG M629Afwd CAACGAGCTcTGGGTCATCgcgGAGTACATGGAGGGAGG LF-3' GTAGGCCATCTAGGCCGCAATCTCGTCAAGTAAAGTCG RF-5' GTAGGCCTGAGTGGCCCGAGATTGCAACGTGTAACC RF-3' GTAGGATCCCGTACGCTGCGATCGCTTGC Ukc1 LF-5' GCAATATTATGTCTACTTTGAGCG M398Arev CCGCCGGGCAAgAAtTCcgcGAGAAGGTACAGATACGc M398Afwd gCGTATCTGTACCTTCTCgcgGAaTTcTTGCCCGGCGG LF-3' GAGGCCATCTAGGCCATTTACGATGGCAGACAAAGG RF-5' GTGGCCTGAGTGGCCATTGGTTTGGGCGAATGGC RF-3' GCAATATTCGTACGTCAACAGCGCG Nrc2 LF-5' GCAATATTTCGAAAAGGGTCGTTCC M454Grev GCCACCCATGCAGTAcTCgccGCAGAGGTAGAGGTAATC M454Gfwd GATTACCTCTACCTCTGCggcGAgTACTGCATGGGTGGC LF-3' GAGGCCATCTAGGCCGACGAGTGAAGCTTTCGAGCG RF-5' GAGGCCTGAGTGGCCTAAGCATCTTGGCTTCTGC RF-3' GCAATATTCGGTCAACGCTTTTCAGATACC Ipl1 LF-5' GTCAATATTCTACTTTGTGAAGACGCTGC M629Arev GCTCCCCACGACCAGCgAATTCGATagcGAGGAAGACTCGGCCCTCATC M629Afwd GATGAGGGCCGAGTCTTCCTCgctATCGAATTcGCTGGTCGTGGGGAGC LF-3' TGAGGCCATCTAGGCCGGTGCCTTAGATTCCGTATAGC RF-5' CATGGCCTGAGTGGCCGATTCTTCTTCTGTCATCGAC RF-3' GACAATATTGCTGACCTTGTCTACTTGG Ire1 LF-5' GCAATATTAAAGCACAACTCAACGC D1014Arev CCGTAGCCAAGCACCTCGgCCGAtATcGTGAGCGAAG D1014Afwd CTTCGCTCACgATaTCGGcCGAGGTGCTTGGCTACGG LF-3' GAGGCCATCTAGGCCAACTGGGCAAAGGAGATGGA RF-5' GAGGCCTGAGTGGCCGTGCGCCTGTGTATCTCTTTG RF-3' GCAATATTGGCCATCTGAGGGCTGAC Kin28 LF-5' GACAATATTCATCTTTCACCCTTCCAAAG L94Arev TGATGAGTGCTTCTAGATTGGTGTCggcGAAcTCgAGCACCAGGTTG L94Afwd CAACCTGGTGCTcGAgTTCgccGACACCAATCTAGAAGCACTCATCA LF-3' TGAGGCCATCTAGGCCCACAGAGATCCGCTTTAATGC RF-5' CATGGCCTGAGTGGCCAGGGCTAGTACGACCTCG -

Genome-Scale Fitness Profile of Caulobacter Crescentus Grown in Natural Freshwater

Supplemental Material Genome-scale fitness profile of Caulobacter crescentus grown in natural freshwater Kristy L. Hentchel, Leila M. Reyes Ruiz, Aretha Fiebig, Patrick D. Curtis, Maureen L. Coleman, Sean Crosson Tn5 and Tn-Himar: comparing gene essentiality and the effects of gene disruption on fitness across studies A previous analysis of a highly saturated Caulobacter Tn5 transposon library revealed a set of genes that are required for growth in complex PYE medium [1]; approximately 14% of genes in the genome were deemed essential. The total genome insertion coverage was lower in the Himar library described here than in the Tn5 dataset of Christen et al (2011), as Tn-Himar inserts specifically into TA dinucleotide sites (with 67% GC content, TA sites are relatively limited in the Caulobacter genome). Genes for which we failed to detect Tn-Himar insertions (Table S13) were largely consistent with essential genes reported by Christen et al [1], with exceptions likely due to differential coverage of Tn5 versus Tn-Himar mutagenesis and differences in metrics used to define essentiality. A comparison of the essential genes defined by Christen et al and by our Tn5-seq and Tn-Himar fitness studies is presented in Table S4. We have uncovered evidence for gene disruptions that both enhanced or reduced strain fitness in lake water and M2X relative to PYE. Such results are consistent for a number of genes across both the Tn5 and Tn-Himar datasets. Disruption of genes encoding three metabolic enzymes, a class C β-lactamase family protein (CCNA_00255), transaldolase (CCNA_03729), and methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase (CCNA_02250), enhanced Caulobacter fitness in Lake Michigan water relative to PYE using both Tn5 and Tn-Himar approaches (Table S7). -

Supplemental Methods

Supplemental Methods: Sample Collection Duplicate surface samples were collected from the Amazon River plume aboard the R/V Knorr in June 2010 (4 52.71’N, 51 21.59’W) during a period of high river discharge. The collection site (Station 10, 4° 52.71’N, 51° 21.59’W; S = 21.0; T = 29.6°C), located ~ 500 Km to the north of the Amazon River mouth, was characterized by the presence of coastal diatoms in the top 8 m of the water column. Sampling was conducted between 0700 and 0900 local time by gently impeller pumping (modified Rule 1800 submersible sump pump) surface water through 10 m of tygon tubing (3 cm) to the ship's deck where it then flowed through a 156 µm mesh into 20 L carboys. In the lab, cells were partitioned into two size fractions by sequential filtration (using a Masterflex peristaltic pump) of the pre-filtered seawater through a 2.0 µm pore-size, 142 mm diameter polycarbonate (PCTE) membrane filter (Sterlitech Corporation, Kent, CWA) and a 0.22 µm pore-size, 142 mm diameter Supor membrane filter (Pall, Port Washington, NY). Metagenomic and non-selective metatranscriptomic analyses were conducted on both pore-size filters; poly(A)-selected (eukaryote-dominated) metatranscriptomic analyses were conducted only on the larger pore-size filter (2.0 µm pore-size). All filters were immediately submerged in RNAlater (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX) in sterile 50 mL conical tubes, incubated at room temperature overnight and then stored at -80oC until extraction. Filtration and stabilization of each sample was completed within 30 min of water collection. -

Structures, Functions, and Mechanisms of Filament Forming Enzymes: a Renaissance of Enzyme Filamentation

Structures, Functions, and Mechanisms of Filament Forming Enzymes: A Renaissance of Enzyme Filamentation A Review By Chad K. Park & Nancy C. Horton Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721 N. C. Horton ([email protected], ORCID: 0000-0003-2710-8284) C. K. Park ([email protected], ORCID: 0000-0003-1089-9091) Keywords: Enzyme, Regulation, DNA binding, Nuclease, Run-On Oligomerization, self-association 1 Abstract Filament formation by non-cytoskeletal enzymes has been known for decades, yet only relatively recently has its wide-spread role in enzyme regulation and biology come to be appreciated. This comprehensive review summarizes what is known for each enzyme confirmed to form filamentous structures in vitro, and for the many that are known only to form large self-assemblies within cells. For some enzymes, studies describing both the in vitro filamentous structures and cellular self-assembly formation are also known and described. Special attention is paid to the detailed structures of each type of enzyme filament, as well as the roles the structures play in enzyme regulation and in biology. Where it is known or hypothesized, the advantages conferred by enzyme filamentation are reviewed. Finally, the similarities, differences, and comparison to the SgrAI system are also highlighted. 2 Contents INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………..4 STRUCTURALLY CHARACTERIZED ENZYME FILAMENTS…….5 Acetyl CoA Carboxylase (ACC)……………………………………………………………………5 Phosphofructokinase (PFK)……………………………………………………………………….6 -

Letters to Nature

letters to nature Received 7 July; accepted 21 September 1998. 26. Tronrud, D. E. Conjugate-direction minimization: an improved method for the re®nement of macromolecules. Acta Crystallogr. A 48, 912±916 (1992). 1. Dalbey, R. E., Lively, M. O., Bron, S. & van Dijl, J. M. The chemistry and enzymology of the type 1 27. Wolfe, P. B., Wickner, W. & Goodman, J. M. Sequence of the leader peptidase gene of Escherichia coli signal peptidases. Protein Sci. 6, 1129±1138 (1997). and the orientation of leader peptidase in the bacterial envelope. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 12073±12080 2. Kuo, D. W. et al. Escherichia coli leader peptidase: production of an active form lacking a requirement (1983). for detergent and development of peptide substrates. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 303, 274±280 (1993). 28. Kraulis, P.G. Molscript: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. 3. Tschantz, W. R. et al. Characterization of a soluble, catalytically active form of Escherichia coli leader J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24, 946±950 (1991). peptidase: requirement of detergent or phospholipid for optimal activity. Biochemistry 34, 3935±3941 29. Nicholls, A., Sharp, K. A. & Honig, B. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and (1995). the thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 11, 281±296 (1991). 4. Allsop, A. E. et al.inAnti-Infectives, Recent Advances in Chemistry and Structure-Activity Relationships 30. Meritt, E. A. & Bacon, D. J. Raster3D: photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277, 505± (eds Bently, P. H. & O'Hanlon, P. J.) 61±72 (R. Soc. Chem., Cambridge, 1997). -

Identification and Characterisation of Mucin Abnormalities in the Ganglionic Bowel in Hirschsprung’S Disease

IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERISATION OF MUCIN ABNORMALITIES IN THE GANGLIONIC BOWEL IN HIRSCHSPRUNG’S DISEASE By Ruth Marian Speare Submitted for MD (Res) 1 Abstract Hirschsprung’s disease (HD) is a congenital abnormality of unknown origin, characterised by a lack of ganglion cells in the distal colon which results in functional colonic obstruction. The major cause of morbidity and mortality in these children results from an inflammatory condition called enterocolitis. Mucins are large glycoproteins produced by intestinal cells which are a vital part of the colonic defensive barrier to infection. Previous work has found that this barrier is deficient in children with HD in the aganglionic colon and in the immediately adjacent ganglionic colon and that this is related to the risk of developing enterocolitis. This study aimed to further investigate the mucin defensive barrier in a greater region of the ganglionic colon in HD, to establish the extent of any mucin deficiencies and whether these were confined to a limited region close to the aganglionic colon. Mucosal biopsies were collected at intervals along the colon at the time of corrective surgery or colostomy closure in the controls. Organ culture with radioactive mucin precursors was performed and the mucin produced was purified and analysed, results quantified by DNA content in the sample. Lectin binding studies were also carried out. Patients were found to produce lower levels of new mucins most distally, but much higher levels five centimetres proximal when compared to controls. The rest of the colon studied also showed changes in mucin production, with a lack of production of gel-forming mucins and sulphated secreted mucins in Hirschsprung’s disease higher up the colon.