Structures, Functions, and Mechanisms of Filament Forming Enzymes: a Renaissance of Enzyme Filamentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

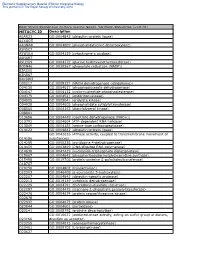

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

The Landscape of Cancer Cell Line Metabolism

The Landscape of Cancer Cell Line Metabolism The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Li, Haoxin, Shaoyang Ning, Mahmoud Ghandi, Gregory V. Kryukov, Shuba Gopal, Amy Deik, Amanda Souza, et. al. 2019. The Landscape of Cancer Cell Line Metabolism. Nature Medicine 25, no. 5: 850-860. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41899268 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Nat Med Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2019 November 08. Published in final edited form as: Nat Med. 2019 May ; 25(5): 850–860. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0404-8. The Landscape of Cancer Cell Line Metabolism Haoxin Li1,2, Shaoyang Ning3, Mahmoud Ghandi1, Gregory V. Kryukov1, Shuba Gopal1, Amy Deik1, Amanda Souza1, Kerry Pierce1, Paula Keskula1, Desiree Hernandez1, Julie Ann4, Dojna Shkoza4, Verena Apfel5, Yilong Zou1, Francisca Vazquez1, Jordi Barretina4, Raymond A. Pagliarini4, Giorgio G. Galli5, David E. Root1, William C. Hahn1,2, Aviad Tsherniak1, Marios Giannakis1,2, Stuart L. Schreiber1,6, Clary B. Clish1,*, Levi A. Garraway1,2,*, and William R. Sellers1,2,* 1Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA 2Department -

WO 2007/084545 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (43) International Publication Date (10) International Publication Number 26 July 2007 (26.07.2007) PCT WO 2007/084545 Al (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agent: ZERULL, Susan, Moeller; The Dow Chemical C07C 227/32 (2006.01) C12P 41/00 (2006.01) Company, Intellectual Property Section, P.O. Box 1967, C07D 317/30 (2006.01) Midland, MI 48674-1967 (US). (21) International Application Number: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every PCT/US2007/001207 kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AT,AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CN, (22) International Filing Date: 17 January 2007 (17.01.2007) CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, (25) Filing Language: English GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, (26) Publication Language: English LT, LU, LV,LY,MA, MD, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, (30) Priority Data: MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, 11/333,937 18 January 2006 (18.01.2006) US RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, SV, SY, TJ, TM, TN, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): DOW TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW GLOBAL TECHNOLOGIES INC. [US/US]; Washing (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every ton Street, 1790 Building, Midland, MI 48674 (US). -

In the Field of Clinical Examination, the Measurement of Creatine

J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr., 3, 17-25, 1987 Bacterial Glucokinase as an Enzymic Reagent of Good Stability for Measurement of Creatine Kinase Activity Hitoshi KONDO, * Takanari SHIRAISHI, Masao KAGEYAMA, Kazuhiko NAGATA, and Kosuke TOMITA Research and Development Center, UNITIKA Ltd., Uji 611, Japan (Received January 10, 1987) Summary An enzymic reagent, that has long-term stability even in the liquid state, was successfully employed for the measurement of serum creatine kinase (CK, EC 2.7.3.2) activity. The enzyme used was the thermostable glucokinase (GlcK, EC 2.7.1.2) obtained from the thermo- phile Bacillus stearothermophilus. The reagent was found to be stable in solution for about one month at 6•Ž and for about one week at 30•Ž. This substitution of glucokinase for the hexokinase of the most commonly used hexokinase-glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (HK-G6PDH) method results in a remarkable improvement of the method. The CK activity measured by the GlcK-G6PDH method was linear up to about 2,000 U/ liter at 37•Ž. The GlcK-G6PDH method was found to give a satisfactory precision and reproducibility (coefficient of variation less than 2.17%). Over a wide range of CK activity, an excellent agreement was obtained between the GlcK-G6PDH and the HK-G6PDH methods. Furthermore several coexistents and anticoagulants were found to have little effect on the measured value of CK activity by the GlcK-G6PDH method. Key Words: creatine kinase activity, glucokinase, improved stability of reagent, creatine kinase determination, thermostable enzyme In the field of clinical examination, the measurement of creatine kinase (CK, ATP : creatine phosphotransferase, EC 2.7.3.2) activity in serum is one of the important examinations usually employed for diagnosis of cardiac diseases such as myocardial infarction or muscular diseases such as progressive muscular dystrophy. -

Screening of a Composite Library of Clinically Used Drugs and Well

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Pharmacol Manuscript Author Res. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 November 01. Published in final edited form as: Pharmacol Res. 2016 November ; 113(Pt A): 18–37. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.016. Screening of a composite library of clinically used drugs and well-characterized pharmacological compounds for cystathionine β-synthase inhibition identifies benserazide as a drug potentially suitable for repurposing for the experimental therapy of colon cancer Nadiya Druzhynaa, Bartosz Szczesnya, Gabor Olaha, Katalin Módisa,b, Antonia Asimakopoulouc,d, Athanasia Pavlidoue, Petra Szoleczkya, Domokos Geröa, Kazunori Yanagia, Gabor Töröa, Isabel López-Garcíaa, Vassilios Myrianthopoulose, Emmanuel Mikrose, John R. Zatarainb, Celia Chaob, Andreas Papapetropoulosd,e, Mark R. Hellmichb,f, and Csaba Szaboa,f,* aDepartment of Anesthesiology, The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, USA bDepartment of Surgery, The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, USA cLaboratory of Molecular Pharmacology, Department of Pharmacy, University of Patras, Greece dCenter of Clinical, Experimental Surgery & Translational Research, Biomedical Research Foundation of the Academy of Athens, Greece eNational and Kapodistrian University of Athens, School of Pharmacy, Athens, Greece fCBS Therapeutics Inc., Galveston, TX, USA Abstract Cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) has been recently identified as a drug target for several forms of cancer. Currently no -

The Cyanide Hydratase from Neurospora Crassa Forms a Helix Which Has a Dimeric Repeat

Appl Microbiol Biotechnol (2009) 82:271–278 DOI 10.1007/s00253-008-1735-4 BIOTECHNOLOGICALLY RELEVANT ENZYMES AND PROTEINS The cyanide hydratase from Neurospora crassa forms a helix which has a dimeric repeat Kyle C. Dent & Brandon W. Weber & Michael J. Benedik & B. Trevor Sewell Received: 2 July 2008 /Revised: 24 September 2008 /Accepted: 25 September 2008 / Published online: 23 October 2008 # Springer-Verlag 2008 Abstract The fungal cyanide hydratases form a functionally Introduction specialized subset of the nitrilases which catalyze the hydrolysis of cyanide to formamide with high specificity. The generation of cyanide containing waste results from These hold great promise for the bioremediation of cyanide cyanide utilization in a variety of applications, spanning wastes. The low resolution (3.0 nm) three-dimensional such diverse industries as gold and silver mining, metal reconstruction of negatively stained recombinant cyanide electroplating, polymer synthesis, and the production of hydratase fibers from the saprophytic fungus Neurospora fine chemicals, pharmaceuticals, dyes, and agricultural crassa by iterative helical real space reconstruction reveals products (Baxter and Cummings 2006). Traditionally, that enzyme fibers display left-handed D1 S5.4 symmetry chemical oxidation or stabilizations are used to treat these with a helical rise of 1.36 nm. This arrangement differs from wastes; however, many groups have been studying the previously characterized microbial nitrilases which demon- potential for bioremediation of such cyanide waste strate a structure built along similar principles but with a (O’Reilly and Turner 2003; Jandhyala et al. 2005). reduced helical twist. The cyanide hydratase assembly is The most promising approach utilizes cyanide degrada- stabilized by two dyadic interactions between dimers across tion by enzymes belonging to the nitrilase family (Pace and the one-start helical groove. -

Cyanide-Degrading Enzymes for Bioremediation A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M University CYANIDE-DEGRADING ENZYMES FOR BIOREMEDIATION A Thesis by LACY JAMEL BASILE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2008 Major Subject: Microbiology CYANIDE-DEGRADING ENZYMES FOR BIOREMEDIATION A Thesis by LACY JAMEL BASILE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved by: Chair of Committee, Michael Benedik Committee Members, Susan Golden James Hu Wayne Versaw Head of Department, Vincent Cassone August 2008 Major Subject: Microbiology iii ABSTRACT Cyanide-Degrading Enzymes for Bioremediation. (August 2008) Lacy Jamel Basile, B.S., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Michael Benedik Cyanide-containing waste is an increasingly prevalent problem in today’s society. There are many applications that utilize cyanide, such as gold mining and electroplating, and these processes produce cyanide waste with varying conditions. Remediation of this waste is necessary to prevent contamination of soils and water. While there are a variety of processes being used, bioremediation is potentially a more cost effective alternative. A variety of fungal species are known to degrade cyanide through the action of cyanide hydratases, a specialized subset of nitrilases which hydrolyze cyanide to formamide. Here I report on previously unknown and uncharacterized nitrilases from Neurospora crassa, Gibberella zeae, and Aspergillus nidulans. Recombinant forms of four cyanide hydratases from N. -

Eradication of ENO1-Deleted Glioblastoma Through Collateral Lethality

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/331538; this version posted May 25, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Eradication of ENO1-deleted Glioblastoma through Collateral Lethality Yu-Hsi Lin1, Nikunj Satani1,2, Naima Hammoudi1, Jeffrey J. Ackroyd1, Sunada Khadka1, Victoria C. Yan1, Dimitra K. Georgiou1, Yuting Sun3, Rafal Zielinski4, Theresa Tran1, Susana Castro Pando1, Xiaobo Wang1, David Maxwell5, Zhenghong Peng6, Federica Pisaneschi1, Pijus Mandal7, Paul G. Leonard8, Quanyu Xu,9 Qi Wu9, Yongying Jiang9, Barbara Czako10, Zhijun Kang10, John M. Asara11, Waldemar Priebe4, William Bornmann12, Joseph R. Marszalek3, Ronald A. DePinho13 and Florian L. Muller#1 1) Department of Cancer Systems Imaging, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77054 2) Institute of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, TX 77030 3) Center for Co-Clinical Trials, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77054 4) Department of Experimental Therapeutics, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77054 5) Institutional Analytics & Informatics, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030 6) Cardtronics, Inc., Houston, TX 77042 7) Department of Genomic Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77054 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/331538; this version posted May 25, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. -

Labeled in Thecourse of Glycolysis, Since Phosphoglycerate Kinase

THE STATE OF MAGNESIUM IN CELLS AS ESTIMATED FROM THE ADENYLATE KINASE EQUILIBRIUM* BY TRWIN A. RoSE THE INSTITUTE FOR CANCER RESEARCH, PHILADELPHIA Communicated by Thomas F. Anderson, August 30, 1968 Magnesium functions in many enzymatic reactions as a cofactor and in com- plex with nucleotides acting as substrates. Numerous examples of a possible regulatory role of Mg can be cited from studies with isolated enzymes,'- and it is known that Mg affects the structural integrity of macromolecules such as trans- fer RNA" and functional elements such as ribosomes.'0 The major problem in translating this information on isolated preparations to the functioning cell is the difficulty in determining the distribution of Mg and the nucleotides among the free and complexed forms that function in the region of the cell for which this information is desired. Nanningall based an attempt to calculate the free Mg2+ and Ca2+ ion concentrations of frog muscle on the total content of these metals and of the principal known ligands (adenosine 5'-triphosphate (ATP), creatine-P, and myosin) and the dissociation constants of the complexes. However, this method suffers from the necessity of evaluating the contribution of all ligands as well as from the assumption that all the known ligands are contributing their full complexing capacity. During studies concerned with the control of glycolysis in red cells and the control of the phosphoglycerate kinase step in particular, it became important to determine the fractions of the cell's ATP and adenosine 5'-diphosphate (ADP) that were present as Mg complexes. Just as the problem of determining the distribution of protonated and dissociated forms of an acid can be solved from a knowledge of pH and pKa of the acid, so it would be possible to determine the liganded and free forms of all rapidly established Mg complexes from a knowledge of Mg2+ ion concentration and the appropriate dissociation constants. -

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution Enhances Methanol Tolerance and Conversion in Engineered Corynebacterium Glutamicum

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-0954-9 OPEN Adaptive laboratory evolution enhances methanol tolerance and conversion in engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum Yu Wang 1, Liwen Fan1,2, Philibert Tuyishime1, Jiao Liu1, Kun Zhang1,3, Ning Gao1,3, Zhihui Zhang1,3, ✉ ✉ 1234567890():,; Xiaomeng Ni1, Jinhui Feng1, Qianqian Yuan1, Hongwu Ma1, Ping Zheng1,2,3 , Jibin Sun1,3 & Yanhe Ma1 Synthetic methylotrophy has recently been intensively studied to achieve methanol-based biomanufacturing of fuels and chemicals. However, attempts to engineer platform micro- organisms to utilize methanol mainly focus on enzyme and pathway engineering. Herein, we enhanced methanol bioconversion of synthetic methylotrophs by improving cellular tolerance to methanol. A previously engineered methanol-dependent Corynebacterium glutamicum is subjected to adaptive laboratory evolution with elevated methanol content. Unexpectedly, the evolved strain not only tolerates higher concentrations of methanol but also shows improved growth and methanol utilization. Transcriptome analysis suggests increased methanol con- centrations rebalance methylotrophic metabolism by down-regulating glycolysis and up- regulating amino acid biosynthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, ribosome biosynthesis, and parts of TCA cycle. Mutations in the O-acetyl-L-homoserine sulfhydrylase Cgl0653 catalyzing formation of L-methionine analog from methanol and methanol-induced membrane-bound transporter Cgl0833 are proven crucial for methanol tolerance. This study demonstrates the importance of -

1 Metabolic Dysfunction Is Restricted to the Sciatic Nerve in Experimental

Page 1 of 255 Diabetes Metabolic dysfunction is restricted to the sciatic nerve in experimental diabetic neuropathy Oliver J. Freeman1,2, Richard D. Unwin2,3, Andrew W. Dowsey2,3, Paul Begley2,3, Sumia Ali1, Katherine A. Hollywood2,3, Nitin Rustogi2,3, Rasmus S. Petersen1, Warwick B. Dunn2,3†, Garth J.S. Cooper2,3,4,5* & Natalie J. Gardiner1* 1 Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, UK 2 Centre for Advanced Discovery and Experimental Therapeutics (CADET), Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Sciences Centre, Manchester, UK 3 Centre for Endocrinology and Diabetes, Institute of Human Development, Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences, University of Manchester, UK 4 School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, New Zealand 5 Department of Pharmacology, Medical Sciences Division, University of Oxford, UK † Present address: School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, UK *Joint corresponding authors: Natalie J. Gardiner and Garth J.S. Cooper Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Address: University of Manchester, AV Hill Building, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PT, United Kingdom Telephone: +44 161 275 5768; +44 161 701 0240 Word count: 4,490 Number of tables: 1, Number of figures: 6 Running title: Metabolic dysfunction in diabetic neuropathy 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online October 15, 2015 Diabetes Page 2 of 255 Abstract High glucose levels in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy (DN). However our understanding of the molecular mechanisms which cause the marked distal pathology is incomplete. Here we performed a comprehensive, system-wide analysis of the PNS of a rodent model of DN. -

Targeting Proteins Self-Association in Drug Design

Targeting proteins self-association in drug design Léopold Thabault,1,2 Maxime Liberelle,1 Raphaël Frédérick1* 1 Louvain Drug Research Institute (LDRI), Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain), B-1200 Brussels, Belgium. 2 Pole of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Institut de Recherche Expérimentale et Clinique (IREC), Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain),B-1200 Brussels, Belgium. * Corresponding Author : Prof. Raphaël Frédérick Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain) Louvain Drug Research Institute (LDRI) Tour Van Helmont, B1.73.10 73 avenue Mounier 1200 Brussels Belgium Phone : +32 2 764 73 41 1 Abstract Protein self-association is a universal phenomenon essential for stability and molecular recognition. Disrupting constitutive homomers constitutes an original and emerging strategy in drug design. Inhibition of homomeric proteins can be achieved through direct complex disruption, subunits intercalation or by promoting inactive oligomeric states. Targeting self- interaction grants several advantages over active site inhibition thanks to the stimulation of protein degradation, the enhancement of selectivity, a sub-stoichiometric inhibition and a by- pass of compensatory mechanisms. This new landscape in protein inhibition is driven by the development of biophysical and biochemical tools suited for the study of homomeric proteins, such as DSF, native MS, FRET spectroscopy, two-dimensional NMR and X-ray crystallography. The present review covers the different aspects of this new paradigm in drug design. Keywords Protein-protein interaction; Homo-oligomers Disruptor; Protein destabilisation; Allosteric inhibition; Self-association. Teaser Disrupting protein self-association bears great therapeutic promesses and could provide exciting alternatives to active-site inhibitors. 2 1. PPI as a well-accepted paradigm in drug design The human interactome is nowadays widely considered as one of the keys to cell mechanistic regulation.