Hong Kong As Alternative Sinophone Articulation: Translation and Literary Cartography in Dung Kai-Cheung’S Atlas: the Archaeology of an Imaginary City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Translation: an Advanced Resource Book

TRANSLATION Routledge Applied Linguistics is a series of comprehensive resource books, providing students and researchers with the support they need for advanced study in the core areas of English language and Applied Linguistics. Each book in the series guides readers through three main sections, enabling them to explore and develop major themes within the discipline: • Section A, Introduction, establishes the key terms and concepts and extends readers’ techniques of analysis through practical application. • Section B, Extension, brings together influential articles, sets them in context, and discusses their contribution to the field. • Section C, Exploration, builds on knowledge gained in the first two sections, setting thoughtful tasks around further illustrative material. This enables readers to engage more actively with the subject matter and encourages them to develop their own research responses. Throughout the book, topics are revisited, extended, interwoven and deconstructed, with the reader’s understanding strengthened by tasks and follow-up questions. Translation: • examines the theory and practice of translation from a variety of linguistic and cultural angles, including semantics, equivalence, functional linguistics, corpus and cognitive linguistics, text and discourse analysis, gender studies and post- colonialism • draws on a wide range of languages, including French, Spanish, German, Russian and Arabic • explores material from a variety of sources, such as the Internet, advertisements, religious texts, literary and technical texts • gathers together influential readings from the key names in the discipline, including James S. Holmes, George Steiner, Jean-Paul Vinay and Jean Darbelnet, Eugene Nida, Werner Koller and Ernst-August Gutt. Written by experienced teachers and researchers in the field, Translation is an essential resource for students and researchers of English language and Applied Linguistics as well as Translation Studies. -

Old Town Central - Enrich Visitor’S Experience

C&WDC WG on DC Affairs Paper No. 2/2017 OldOld TTownown CCentralentral 1 Old Town Central - Enrich Visitor’s Experience A contemporary lifestyle destination and a chronicle of how Arts, Heritage, Creativity, and Dining & Entertainment evolved in the city Bounded by Wyndham Street, Caine Road, Possession Street and Queen’s Road Central Possession Street Queen’s Road Central Caine Road Wyndham Street Key Campaign Elements DIY Walking Guide Heritage & Art History Integrated Marketing Local & Overseas Publicity Launch Ceremony City Ambience Tour Products 3 5 Thematic ‘Do-It-Yourself’ Routes For visitors to explore the abundant treasure according to their own interests and pace. Heritage & Dining & Art Treasure Hunt All-in-one History Entertainment Possession Street, Tai Ping Shan PoHo, Upper PMQ, Hollywood Graham market & Best picks Street, Lascar Row, Road, Peel Street, around, LKF, from each Man Mo Temple, StauntonS Street & Aberdeen Street SoHo, Ladder Street, around route Tai Kwun 4 Sample route: All-in-one Walking Tour Route for busy visitors 1. Possession Street (History) 1 6: Gough Street & Kau U Fong (Creative & Design – Designer stores, boutiques 2 4: Man Mo Temple Dining – Local food stalls & (Heritage - Declared International cuisine) 2: POHO - Tai Ping Shan Street (Local Monument ) culture – Temples / Stores/ Restaurant) 6 (Art & Entertainment – Galleries / 4 Street Art/ Café ) 3 7 5 7: Pak Tsz Lane Park 5: PMQ (History) 3: YMCA Bridges Street Centre & ( Heritage - 10: Pottinger Ladder Street Arts & Dining – Galleries, Street -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Introduction to the Paratext Author(S): Gérard Genette and Marie Maclean Source: New Literary History, Vol

Introduction to the Paratext Author(s): Gérard Genette and Marie Maclean Source: New Literary History, Vol. 22, No. 2, Probings: Art, Criticism, Genre (Spring, 1991), pp. 261-272 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/469037 Accessed: 11-01-2019 17:12 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to New Literary History This content downloaded from 128.227.202.135 on Fri, 11 Jan 2019 17:12:58 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Introduction to the Paratext* Gerard Genette HE LITERARY WORK consists, exhaustively or essentially, of a text, that is to say (a very minimal definition) in a more or less lengthy sequence of verbal utterances more or less con- taining meaning. But this text rarely appears in its naked state, without the reinforcement and accompaniment of a certain number of productions, themselves verbal or not, like an author's name, a title, a preface, illustrations. One does not always know if one should consider that they belong to the text or not, but in any case they surround it and prolong it, precisely in order to present it, in the usual sense of this verb, but also in its strongest meaning: to make it present, to assure its presence in the world, its "reception" and its consumption, in the form, nowadays at least, of a book. -

Register of Public Payphone

Register of Public Payphone Operator Kiosk ID Street Locality District Region HGC HCL-0007 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HGC HCL-0010 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HGC HCL-0024 Des Voeux Road Central Outside Wheelock House Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2338 Caine Road Outside Albron Court Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1488 Caine Road Outside Ho Shing House, near Central - Mid-Levels Central and HK Escalators Western HKT HKT-1052 Caine Road Outside Long Mansion Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1090 Charter Garden Near Court of Final Appeal Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1042 Chater Road Outside St George's Building, near Exit F, MTR's Central Central and HK Station Western HKT HKT-1031 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1076 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1050 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Bus Stop Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1062 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Court of Final Appeal Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1072 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Court of Final Appeal Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2321 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Prince's Building Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2322 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Prince's Building Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2323 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Prince's Building Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2337 Conduit Road Outside Elegant Garden Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1914 Connaught Road Central Outside Shun Tak -

Designated 7-11 Convenience Stores

Store # Area Region in Eng Address in Eng 0001 HK Happy Valley G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK 0009 HK Quarry Bay Shop 12-13, G/F., Blk C, Model Housing Est., 774 King's Road, HK 0028 KLN Mongkok G/F., Comfort Court, 19 Playing Field Rd., Kln 0036 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, TAL Building, 45-53 Austin Road, Kln 0077 KLN Kowloon City Shop A-D, G/F., Leung Ling House, 96 Nga Tsin Wai Rd, Kowloon City, Kln 0084 HK Wan Chai G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK 0085 HK Sheung Wan G/F., Blk B, Hiller Comm Bldg., 89-91 Wing Lok St., HK 0094 HK Causeway Bay Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0102 KLN Jordan G/F, 11 Nanking Street, Kln 0119 KLN Jordan G/F, 48-50 Bowring Street, Kln 0132 KLN Mongkok Shop 16, G/F., 60-104 Soy Street, Concord Bldg., Kln 0150 HK Sheung Wan G01 Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Rd C, HK-Macau Ferry Terminal, HK 0151 HK Wan Chai Shop 2, 20 Luard Road, Wanchai, HK 0153 HK Sheung Wan G/F., 88 High Street, HK 0226 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, Cheung King Mansion, 144 Austin Road, Kln 0253 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui East Shop 1, Lower G/F, Hilton Tower, 96 Granville Road, Tsimshatsui East, Kln 0273 HK Central G/F, 89 Caine Road, HK 0281 HK Wan Chai Shop A, G/F, 151 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, HK 0308 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 1 & 2, G/F, Hart Avenue Plaza, 5-9A Hart Avenue, TST, Kln 0323 HK Wan Chai Portion of shop A, B & C, G/F Sun Tao Bldg, 12-18 Morrison Hill Rd, HK 0325 HK Causeway Bay Shop C, G/F Pak Shing Bldg, 168-174 Tung Lo Wan Rd, Causeway Bay, HK 0327 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 7, G/F Star House, 3 Salisbury Road, TST, Kln 0328 HK Wan Chai Shop C, G/F, Siu Fung Building, 9-17 Tin Lok Lane, Wanchai, HK 0339 KLN Kowloon Bay G/F, Shop No.205-207, Phase II Amoy Plaza, 77 Ngau Tau Kok Road, Kln 0351 KLN Kwun Tong Shop 22, 23 & 23A, G/F, Laguna Plaza, Cha Kwo Ling Rd., Kwun Tong, Kln. -

General Post Office 2 Connaught Place, Central Postmaster 2921

Access Officer - Hongkong Post District Venue/Premise/Facility Address Post Title of Access Officer Telephone Number Email Address Fax Number General Post Office 2 Connaught Place, Central Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 G/F, Kennedy Town Community Complex, 12 Rock Kennedy Town Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Hill Street, Kennedy Town Shop P116, P1, the Peak Tower, 128 Peak Road, the Peak Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Peak Central and Western Sai Ying Pun Post Office 27 Pok Fu Lam Road Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 1/F, Hong Kong Telecom CSL Tower, 322-324 Des Sheung Wan Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Voeux Road Central Wyndham Street Post Office G/F, Hoseinee House, 69 Wyndham Street Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Gloucester Road Post Office 1/F, Revenue Tower, 5 Gloucester Road, Wan Chai Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Happy Valley Post Office G/F, 14-16 Sing Woo Road, Happy Valley Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Morrison Hill Post Office G/F, 28 Oi Kwan Road, Wan Chai Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Wan Chai Wan Chai Post Office 2/F Wu Chung House, 197-213 Queen's Road East Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Perkins Road Post Office G/F, 5 Perkins Road, Jardine's Lookout Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Shops 1015-1018, 10/F, Windsor House, 311 Causeway Bay Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Gloucester -

Queer Zines and the Active Subject

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2006 Cultivating dissent: Queer zines and the active subject Angela Connie Asbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Asbell, Angela Connie, "Cultivating dissent: Queer zines and the active subject" (2006). Theses Digitization Project. 3003. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3003 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CULTIVATING DISSENT: QUEER ZINES AND THE ACTIVE SUBJECT A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Angela Connie Asbell September 2006 CULTIVATING DISSENT: QUEER ZINES AND THE ACTIVE SUBJECT A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Angela Connie Asbell September 2006 Approved by: Date Rong Then ABSTRACT This study performs a rhetorical analysis of several zines that deal with gender and sexual identity. Zines are self-published, non-commercial magazines that highlight the individual creativity in writing and the participatory aspects to writing, publishing, and distributing texts. The Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethic is the centerpiece of political self- motivation and connection to other activists through non-hierarchical media forms. Through the employment of a subversive rhetoric blending pastiche, performativity, and moments of strategic essentialism, zinesters create meaning, through the disruption of meaning. -

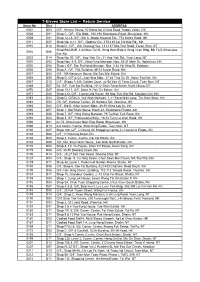

7-Eleven Store List – Return Service Store No

7-Eleven Store List – Return Service Store No. Dist ADDRESS 0001 D03 G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK 0008 D01 Shop C, G/F., Elle Bldg., 192-198 Shaukiwan Road, Shaukiwan, HK 0009 D01 Shop 12-13, G/F., Blk C, Model Housing Est., 774 King's Road, HK 0011 D07 Shop No. 6-11, G/F., Godfrey Ctr., 175-185 Lai Chi Kok Rd., Kln 0015 D12 Shop D., G/F., Win Cheung Hse, 131-137 Sha Tsui Road, Tsuen Wan, NT Shop B2A,B2B, 2-32 Man Tai St, Wing Wah Bldg & Wing Yuen Bldg, Blk F&G,Whampoa 0016 D06 Est, Kln 0022 D14 Shop No. 57, G/F., Hop Yick Ctr., 31 Hop Yick Rd., Yuen Long, NT 0030 D02 Shop Nos. 6-9, G/F., Ning Fung Mansion, Nos. 25-31 Main St., Apleichau, HK 0035 D04 Shop J G/F, San Po Kong Mansion, Nos. 2-32 Yin Hing St, Kowloon 0036 D06 Shop A, G/F, TAL Building, 45-53 Austin Road, Kln 0037 D04 G/F, 109 Geranum House, Ma Tau Wai Estate, Kln 0058 D05 Shop D, G/F & C/L, Lap Hing Bldg., 37-43 Ting On St., Ngau Tau Kok, Kln 0067 D13 G/F., Shops A & B, Golden Court, 42-58 Yan Oi Tong Circuit, Tuen Mun, NT 0069 D07 B2, G/F, Yuet Bor Building, 10-12 Shun Fong Street, Kwai Chung, NT 0070 D07 Shop 15-17, G/F, Block 9, Pak Tin Estate, Kln 0077 D08 Shop A-D, G/F., Leung Ling House, 96 Nga Tsin Wai Rd, Kowloon City, Kln 0083 D04 Shop D, G/F&C/L Yuk Wah Mansion, 1-11 Fong Wah Lane, Tsz Wan Shan, Kln 0084 D03 G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK 0085 D02 G/F., Blk B, Hiller Comm Bldg., 89-91 Wing Lok St., HK 0086 D07 Shop 1, Mei Shan House, Block 42, Shekkipmei Estate, Kln 0093 D08 Shop 7, G/F, Hing Wong Mansion, 79 Tai Kok Tsui Road, Kln 0094 D03 Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0096 D01 62-74, Shaukiwan Main East Road, Shaukiwan, HK 0098 D13 8-9 Comm. -

Major Smartone Authorised Resellers

Major SmarTone Authorised Resellers Hong Kong News stand G/F, Aberdeen Municipal Service Building, 203 Aberdeen Main Road, Aberdeen News stand 12 Sai On Street, Aberdeen News stand Shop 13, Block B, Lei Tim House, Ap Lei Chau Estate (West), Ap Lei Chau Aberdeen News stand Shop 6, G/F, 150 Ap Lei Chau Main Street, Ap Lei Chau Convenience Store G/F, 10 Tin Wan Street, Tin Wan, Aberdeen Photo Printing Shop Shop 24, Wah Fu (I) Commercial Complex, Wah Fu Estate, Aberdeen News stand G/F, 18 Stanley Main Street, Stanley Stanley News stand 94A Stanley Main Street, Stanley News stand G/F, 568 Queen's Road West, Kennedy Town Kennedy Town News stand Shop G03, G/F, Smithfield Municipal Services Building, 12K Smithfield Road, Kennedy Town A Plus Phone Store Shop F04, 1/F, Chong Yip Centre, 402-404 Des Voeux Road West, Sai Ying Pun Sai Ying Pun News stand 343 Des Voeux Road West, Sai Ying Pun Telecom Shop Shop 43B1, 343 Des Voeux Road West, Sai Wan Sai Wan Telecom Shop Shop A4, G/F, Man Fat Building, 30 Belcher's Street, Sai Wan Me Too Photo Service Limited Shop 1A, G/F, 43 Smithfield Road, Sai Wan News stand Shop NP2, G/F, Sheung Wan Municipal Services Building, 345 Queen's Road Central, Sheung Wan News stand 237-239 Des Voeux Road Central, Sheung Wan Sheung Wan News stand 33 Hillier Street, Sheung Wan Mobile One Shop 282, Shun Tak Centre, 168-200 Connaught Road Central, Sheung Wan Convenience Store Shop A, G/F, 27 High Street, Sheung Wan News stand 20 Des Voeux Road Central, Central (Central MTR Exit C) News stand World Wide House, Des Voeux Road -

A Dictionary of Translation and Interpreting

1 A DICTIONARY OF TRANSLATION AND INTERPRETING John Laver and Ian Mason 1 2 This dictionary began life as part of a much larger project: The Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Speech and Language (General Editors John Laver and Ron Asher), involving nearly 40 authors and covering all fields in any way related to speech or language. The project, which from conception to completion lasted some 25 years, was finally delivered to the publisher in 2013. A contract had been signed but unfortunately, during a period of ill health of editor-in- chief John Laver, the publisher withdrew from the contract and copyright reverted to each individual contributor. Translation Studies does not lack encyclopaedic information. Dictionaries, encyclopaedias, handbooks and readers abound, offering full coverage of the field. Nevertheless, it did seem that it would be a pity that the vast array of scholarship that went into The Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Speech and Language should come to nought. Consequently, we offer this small sub-part of the entire project as a free-to-use online resource in the hope that it will prove to be of some use, at least to undergraduate and postgraduate students of translation studies – and perhaps to others too. Each entry consists of a headword, followed by a grammatical categoriser and then a first sentence that is a definition of the headword. Entries are of variable length but an attempt is made to cover all areas of Translation Studies. At the end of many entries, cross-references (in SMALL CAPITALS) direct the reader to other, related entries. Clicking on these cross- references (highlight them and then use Control and right click) sends the reader directly to the corresponding headword. -

Chapter One Introduction Chapter Two the 1920S, People and Weather

Notes Chapter One Introduction 1. Steve Tsang, ed., Government and Politics (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1995); David Faure, ed., Society (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1997); David Faure and Lee Pui-tak, eds., Economy (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004); and David Faure, Colonialism and the Hong Kong Mentality (Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong, 2003). 2. Cindy Yik-yi Chu, The Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, 1921–1969: In Love with the Chinese (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), book jacket. Chapter Two The 1920s, People and Weather 1. R. L. Jarman, ed., Hong Kong Annual Administration Reports 1841–1941, Archive ed., Vol. 4: 1920–1930 (Farnham Common, 1996), p. 26. 2. Ibid., p. 27. 3. S. G. Davis, Hong Kong in Its Geographical Setting (London: Collins, 1949), p. 215. 4. Vicariatus Apostolicus Hongkong, Prospectus Generalis Operis Missionalis; Status Animarum, Folder 2, Box 10: Reports, Statistics and Related Correspondence (1969), Accumulative and Comparative Statistics (1842–1963), Section I, Hong Kong Catholic Diocesan Archives, Hong Kong. 5. Unless otherwise stated, quotations in this chapter are from Folders 1–5, Box 32 (Kowloon Diaries), Diaries, Maryknoll Mission Archives, Maryknoll, New York. 6. Cindy Yik-yi Chu, The Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, 1921–1969: In Love with the Chinese (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), pp. 21, 28, 48 (Table 3.2). 210 / notes 7. Ibid., p. 163 (Appendix I: Statistics on Maryknoll Sisters Who Were in Hong Kong from 1921 to 2004). 8. Jean-Paul Wiest, Maryknoll in China: A History, 1918–1955 (Armonk: M.E.