MEIEA 2008.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aes 143Rd Convention Program October 18–21, 2017

AES 143RD CONVENTION PROGRAM OCTOBER 18–21, 2017 JAVITS CONVENTION CENTER, NY, USA The Winner of the 143rd AES Convention To be presented on Friday, Oct. 20, Best Peer-Reviewed Paper Award is: in Session 15—Posters: Applications in Audio A Statistical Model that Predicts Listeners’ * * * * * Preference Ratings of In-Ear Headphones: Session P1 Wednesday, Oct. 18 Part 1—Listening Test Results and Acoustic 9:00 am – 11:00 am Room 1E11 Measurements—Sean Olive, Todd Welti, Omid Khonsaripour, Harman International, Northridge, SIGNAL PROCESSING CA, USA Convention Paper 9840 Chair: Bozena Kostek, Gdansk University of Technology, Gdansk, Poland To be presented on Thursday, Oct. 18, in Session 7—Perception—Part 2 9:00 am P1-1 Generation and Evaluation of Isolated Audio Coding * * * * * Artifacts—Sascha Dick, Nadja Schinkel-Bielefeld, The AES has launched an opportunity to recognize student Sascha Disch, Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated members who author technical papers. The Student Paper Award Circuits IIS, Erlangen, Germany Competition is based on the preprint manuscripts accepted for the Many existing perceptual audio codec standards AES convention. define only the bit stream syntax and associated decod- A number of student-authored papers were nominated. The er algorithms, but leave many degrees of freedom to the excellent quality of the submissions has made the selection process encoder design. For a systematic optimization of encod- both challenging and exhilarating. er parameters as well as for education and training of The award-winning student paper will be honored during the experienced test listeners, it is instrumental to provoke Convention, and the student-authored manuscript will be consid- and subsequently assess individual coding artifact types ered for publication in a timely manner for the Journal of the Audio in an isolated fashion with controllable strength. -

7 41 F.2D 896 United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit

7 41 F.2d 896 United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit. Ronald H. SELLE, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Barry GIBB, et al., Defendants-Appellants, and Ronald H. SELLE, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. Barry GIBB, et al., Defendants-Appellants. Nos. 83–2484, 83–2545. | Argued April 13, 1984. | Decided July 23, 1984. Opinion CUDAHY, Circuit Judge. The plaintiff, Ronald H. Selle, brought a suit against three brothers, Maurice, Robin and Barry Gibb, known collectively as the popular singing group, the Bee Gees, alleging that the Bee Gees, in their hit tune, “How Deep Is Your Love,” had infringed the copyright of his song, “Let It End.” The jury returned a verdict in plaintiff’s favor on the issue of liability in a bifurcated trial. The district court, Judge George N. Leighton, granted the defendants’ motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict and, in the alternative, for a new trial. Selle v. Gibb, 567 F.Supp. 1173 (N.D.Ill.1983). We affirm the grant of the motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict. I Selle composed his song, “Let It End,” in one day in the fall of 1975 and obtained a copyright for it on November 17, 1975. He played his song with his small band two or three times in the Chicago area and sent a tape and lead sheet of the music to eleven music recording and publishing companies. Eight of the companies returned the materials to Selle; three did not respond. This was the extent of the public dissemination of Selle’s song.1 Selle first became aware of the Bee Gees’ song, “How Deep Is Your Love,” in May 1978 and thought that he recognized the music as his own, although the lyrics were different. -

LIT2013000004 - Andy Gibb.Pdf

•, \.. .. ,-,, i ~ .«t ~' ,,; ~-· ·I NOT\CE OF ENTR'Y.OF APPEARANCE AS AllORNE'< OR REPRESEN1' Al\VE DATE In re: Andrew Roy Gibb October 27, 1978 application for status as permanent resident FILE No. Al I (b)(6) I hereby enter my appearanc:e as attorney for (or representative of), and at the reQUest of, the fol'lowing" named person(s): - NAME \ 0 Petitioner Applicant Andrew Roy Gibb 0 Beneficiary D "ADDRESS (Apt. No,) (Number & Street) (City) (State) (ZIP Code) Mi NAME O Applicant (b)(6) D ADDRESS (Apt, No,) (Number & Street) (City} (ZIP Code) Check Applicable ltem(a) below: lXJ I I am an attorney and a member in good standing of the bar of the Supreme Court of the United States or of the highest court of the following State, territory; insular possession, or District of Columbia A;r;:ka.nsa§ Simt:eme Coy;ct and am not under -a (NBme of Court) court or administrative agency order ·suspending, enjoining, restraining, disbarring, or otherwise restricting me in practicing law. [] 2. I am an accredited representative of the following named religious, charitable, ,social service, or similar organization established in the United States and which is so recognized by the Board: [] i I am associated with ) the. attomey of record who previously fited a notice of appearance in this case and my appearance is at his request. (If '!J<?V. check this item, also check item 1 or 2 whichever is a1wropriate .) [] 4. Others (Explain fully.) '• SIGNATURE COMPLETE ADDRESS Willi~P .A. 2311 Biscayne, Suite 320 ' By: V ? Litle Rock, Arkansas 72207 /I ' f. -

Albhy Galuten

Albhy Galuten Producer, Musician & Songwriter 1970 –1992 Grammy Award-winning record producer, song writer and composer, musician, orchestrator and conductor. Produced 18 number 1 singles with songs and albums selling over 100 million copies. Awarded two Grammy Awards, multiple gold and platinum records, a Drama-Logue award and a BMI award. The inventor of the Drum Loop for Stayin’ Alive from Saturday Night Fever Technology Executive 1993 – Present Began his technology career in 1993 at Ion where he invented and developed the Enhanced CD. Then started Elabs Technology group at Universal Music Group as Senior Vice President. Currently VP of Media Technology for Sony Interactive Entertainment. 6 Patents Issued, 8 more Pending. Infinite Monkeys the hollywIDEAood process The Hollywood Process IDEA AN AGENT A LAWYER PITCHING SKILLS PATIENCE PEOPLE with a track record (and money) have to believe success is likely next gen process STILL NEED AN IDEA GATHER FRIENDS AND START TWEET AND SHARE PRAY AND WAIT EARN NOTHING PRODUCTION PROCESS TRADITIONAL NEXT GEN PRODUCTION COMPANY IDEA GATHER FRIENDS AGENT FILM LAWYER EFFECTS/RENDER STUDIO/NETWORK EDIT WRITERS DISTRIBUTE: YOUTUBE LINE PRODUCER/DIRECTOR ACTORS DP/CAMERA/GRIPS SHOOT FILM EFFECTS/RENDER EDIT DISTRIBUTE: THEATERS/TV 1-5 YEARS TIME 1-5 MONTHS LEGAL & GENERALLY CLEAR NON-EXISTENT FINANCIAL on the horizon RESOURCES COMING HERE HIGH QUALITY VIDEO CAMERAS CLOUD STORAGE AND ACCESS EDITING/RENDERING/ANIMATING/EFFECTS TOOLS IMPACT OF SOCIAL NETWORKS RESOURCES COMING HERE HIGH QUALITY VIDEO CAMERAS CLOUD STORAGE AND ACCESS EDITING/RENDERING/ANIMATING/EFFECTS TOOLS IMPACT OF SOCIAL NETWORKS media consumption and distribution US Pay-TV Households 2010-2017 102 Millions of US Households 101 100 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 92 91 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Disposable Income 49% of Millennials are likely to enter the ‘sharing economy’ as Games and Toys part time proprietors (e.g. -

NMI R the INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY of MUSIC, VIDEO, and HOME ENTERTAINMENT JULY 10, 1999

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) 11.1..11...1..1,11.1...1..11..1..111 I Iln.11 908 #BXNCCVR 3-DIGIT BLBD 690 A06 B0059 #90807GEE374EM002# 001 032500 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 Elmo/ NMI r THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT JULY 10, 1999 Z 2 GEORGE Top Court Ruling As Used -CD Biz O Vid Biz In Transition Spurs Concerns Grows, Chains IAMOND Internet, DVD, Chains Among factors Reshaping Landscape Over Copyright BY SETH GOLDSTEIN of those rental fixtures in the U.S., Get In On Act Ills first SALSA production and EILEEN FITZPATRICK the neighborhood stores. "I hate to BY BILL HOLLAND NEW YORK -Independent video say it, but I believe" the small indies BY ED CHRISTMAN WASHINGTON, D.C. -The retailers used to control video retail- are an endangered species, says con- NEW YORK -With the used- containsENNANCED CE with June 23 U.S. Supreme Court rul- ing. No longer. sultant Richard Kelly CD business apparently on an video and interview ing that gives states immunity The growth of of Cambridge Associ- upswing at independent stores, from private lawsuits seeking chains like Blockbuster ates in Stamford, Conn. more U.S. chains are beginning His first single damages for patent and trade- and Hollywood Enter- Rentrak, the rev- to add the prod- mark violations tainment, the emer- enue-sharing specialist uct category to "QUE 111 VAS" NEWS does not yet gence of the Internet that regularly collects their stores. -

November 1990

FEATURES INSIDE COLLARLOCK In an almost silent way, Mark Gauthier of Collarlock has been BOBBY a major contributor to the recent drum rack revolution. In ELLIOTT this special industry profile, Gauthier explains the nuts and LA. STUDIO Not too many bands have bolts (and much more) of build- remained together—and suc- ing the unique ROUND TABLE cessful—as long as the Hollies. Collarlock system. Bobby Elliott's drumming has • by Rick Van Horn been an integral part of the 30 Colaiuta, Keltner, Porcaro, Mason, Baird, Fongheiser, and band's sound since they began Schaeffer—seven of the most recording. Find out why drum- respected and requested drum- mers like Phil Collins and Cozy mers recording today. Put 'em Powell understand the value of in a room together and press Elliott's contributions to the the record button, and what Hollies' timeless MD TRIVIA have you got? Read music. on...and LEARN. •by Simon Goodwin 26 CONTEST • by Robyn Flans 18 Win a set of Paiste Sound Formula Cymbals! 64 Cover Photo: Lissa Wales COLUMNS Education 56 ROCK PERSPECTIVES The Benefits Of A Four-Piece Kit Equipment BY ANDY NEWMARK 36 PRODUCT 66 ROCK 'N' CLOSE-UP Departments JAZZ CLINIC Corder Celebrity Applying Cross Drumkit News Rhythms To The 4 EDITOR'S Drumset Part 2 BY RICK VAN HORN OVERVIEW UPDATE BY ROD MORGENSTEIN 8 38 Remo Legacy Michael Hodges, Drumheads 6 READERS' Marillion's Ian Mosley, 68 THE MACHINE BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Jerry Fehily of SHOP Hothouse Flowers, Drum Machines 40 Vic Firth Signature Bobby Z, plus News A To Z Drumsticks 12 ASK A PRO BY RIC FURLEY BY RICK MATTINGLY 14 IT'S Profiles STRICTLY 42 Nady SongStarter QUESTIONABLE 74 BY ADAM BUDOFSKY PORTRAITS TECHNIQUE 58 Rhythmic Rudimental IMPAC Snare 124 DRUM MARKET Dom Um Romao Progressions: Part 6 Replacement BY FRANK COLON BY JOE MORELLO BY WILLIAM F. -

Toque De Consciência

comportamento TOQUE DE CONSCIÊNCIA “A minha consciência tem milhares de vozes E cada voz traz-me milhares de histórias E de cada história sou o vilão condenado.” Shakespeare, Rei Ricardo II, ato V. Você tem medo da morte? Não se deses- humano e investigador das áreas cerebrais respon- pere. Não porque seja uma das duas coisas inevi- sáveis pela tomada de decisões e conduta, que em táveis – outra são impostos –, e sim porque é essa 2010 editou o a obra O Livro da Consciência. Antes, já mesma consciência que permite a alguns ouvir a nona tinha lançado O Erro de Descartes e E o Cérebro criou de Beethoven e sentir a leveza alada ou perceber a o Homem, entre outros livros. música nos versos de seu poeta preferido. Em vez de olhar o comportamento e interpretá-lo, Consciência é uma nova maneira de observá-la que é o usual, devemos olhar a mente e pesquisá-la. e escutá-la. É isso que tenta fazer o neurocientista Tentar buscar técnicas científicas que permitam expli- português António Damásio, hoje professor de Neu- cá-la. Tarefa hercúlea e, talvez, inalcançável, daí o rociência na University of Southern California (EUA). termo mistério – aquilo que desafia. Ciência é assim, Um estudioso de neurobiologia do comportamento sem limites, movida a curiosidades. INFLUÊNCIAS E TRANSFERÊNCIAS... A ideia de consciência está ainda em seu estádio pri- nheça a existência do inconsciente ou que negue suas mário, mas quem participou do primeiro campeonato virtudes de grande escritor, capaz de influenciar toda a jogando como craque foi o velho Freud – não reparem, vida cultural, incluindo a invenção de uma linguagem. -

Preowned 1970S Sheet Music

Preowned 1970s Sheet Music. PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR CONDITION AND PRICES PER TITLE ex No marks or deteriation Priced £15. good As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Slight marks on front cover (shop stamp or owner's name). Possible slight marking (pencil) inside. Priced £12. fair Some damage such as edging tears. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered.. Year Year of print. Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a No artist photo on front cover LOOKING FOR THESE ARTISTS? You’ve come to the right place for The Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Russ Conway, John B.Sebastian, Status Quo or even “Woodstock”. Just look for the artist’s name on the lists below. Email us if the title you’re looking for, isn’t here. We may still be able to get it for you. STAMP OUT FORGERIES. Although we take every reasonable precaution to ensure that the items we have for sale are genuine and from the period described, we urge buyers to verify purchases from us and bring to our attention any item discovered to be fake or falsely described. The public can thus be warned and the buyer recompensed. Your cooperation is appreciated. 1970s Title Writer and composer condition Photo year Abba Greatest Hits 19 songs B.Andersson/B.Ulvaeus album Abba © 1992 After the goldrush Neil Young ex Prelude 1970 Albertross Peter Green fair Fleetwood Mac 1970 Albertross (piano solo) Peter Green ex n/a © 1970 All around -

Who's Who in Pop Record Production

WHO'S WHO IN POP RECORD PRODUCTION The following is a list of producers who had at least one single and/or album in the Top Pop 100 charts last year (1986). The producer's name is followed by the (S) song title(s) and/or (LP) album title(s) in quotes, with the artist's name in all capitol letters, followed by a slash and the name(s) of any co- producer(s). Colonel Abrams (S)-(LP)-"Colonel Abrams"-COLONEL ABRAMS-/ /Richard The Bunnymen (S)-(LP)-"Songs To Learn And Sing"-ECHO & THE James Burgess/Rick Dees BUNNYMEN-/Ian Broudie/Bill Drummond/Hugh Jones William Ackerman (S)-(LP)-"Winter's Solstice"-VARIOUS-/Dawn Atkinson Richard James (S)-"Can't Wait Another Minute"-FIVE Alabama (S)-(LP)-"Christmas"-ALABAMA-/Harold Shedd Burgess STAR-/(LP)-"Colonel Abrams"-COLONEL ABRAMS-/Colonel "Alabama Greatest Hits"-ALABAMA-/Harold Shedd Abrams/ /Rick Dees "The Touch"-ALABAMA-/Harold Shedd T-Bone Burnett (S)-(LP)-"King Of America"-ELVIS COSTELLO & THE Teneen Ali (S)-"For Tonight"-NANCY MARTINEZ-/Sergio Munzibal(LP)- ATTRACTIONS-/Declan Patrick A. MacManus Dave Allen (S)-"In Between Days"-THE CURE-/Robert Smith(LP)- Joe Busby (S)-(LP)-"Al I In Love"-NEW EDITION-/Bill Dern Tom Allom (S)-"This Could Be The Night"-LOVERBOY-/Paul Dean Jonathan Cain (S)-"Working Class Man"-JIMMY BARNES-/UP)- "Lead A Double Life"-LOVERBOY-/Paul Richard Calandra (S)-(LP)-"Breakout"-SPYRO GYRA-/Jay Becknestein Dean(LP)-"Turbo"-JUDAS PRIEST-/ The Call (S)-(LP)-"Reconciled"-THE CALL-/Michael Been Pete Anderson (S)-(LP)-"Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc."-DWIGHT Reggie Calloway (S)-"Headlines"-MIDNIGHT -

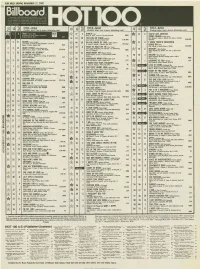

RWC°Atp8eritie. Sweet Harmony

FOR WEEK ENDING NOVEMBER 27, 1982 72 c Copyright 1982 Billboard Publications. Inc No part illboarof this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- Bdtne al system. Or transmitted. in any form or by any means electronic mechanical, photocopying, record- ing. or otherwise without the onor written permission of the pub sher OR 76 TITLE -Artist TITLE -Artist TITLE -Artist HOTIO F- 5g (Producer) Writer, Label & Number (Distributing Label) (Producer) Writer, Label & Number (Distributing Label) (Producer) Writer, Label & Number (Distributing Label) 2 TRULY-Lionel Richie WEEKS 5 AT h 1 37 AFRICA-Toth 73 YOU'VE GOT ANOTHER (Lionel Richie, James Anthony Carmichael) (Iota), 0. Paich, 1.Porcaro; Columbia 36-03335 WBM L Richie. Motown 1644 1 CLM THING COMING-Judas Priest 34 23 18 YOU CAN DO MAGIC-America (Tom Allorn), G. Tipton, FMallard, K.K. Dowmg; Columbia (Russ Ballard), R. Ballard; Capitol 5142 CLM APB 18-03168 CLM. APB 21 GLORIA-Laura Branigan 40 10 ON THE WINGS OF LOVE-Jeffrey Osborne 74 I KNOW THERE'S SOMETHING IiTour, G. (lack White), CdProduced-Greg ktathieson; (G. Duke). P. Schless,J. Osborne; UM 2434 CPI': ALM Bigazzi,T. Veitch, Atlantic 4048 MCA GOING ON-Freda (Phil Collins),R. Ballard; Atlantic 789984 CLM APB 44 4 HAND TO HOLD ON TO-John Cougar 13 HEART ATTACK-Olivia Newiontohn IN (John Cougar Mellencamp. Don Gehman),I.C. Mdlencamp; 79 MEMORY-Barry Manilow (John Farrar), S. Kipner. PBliss; MCA 52100 CLM-APB Rini 211 (Polygram) WBM (Barry Manilow), A.L Webber. T.S.Eliot,T. NunnArista 1025 15 UP WHERE WE BELONG- 41 11 WHAT ABOUT ME-Moving Pictures Joe Cocker And lennder Warne: (Charles Fisher), G. -

New Acts: Labels Play Lt Tight by PAUL GREI\ Signings Is Brighter Than It :Rs During in Fixing Mechanical Payments

NEW 1JMPLJT[FI UFTWA1L WAFTB See Page 30 SM 14011 E8049GRE CM_ YMONT00 MAAF4 MONTY GREENLY 03 10 NEWSPAPER 374G ELM UCY z LONG LEACH CA 90P07 L A Billboard Publication The International Newsweekly Of Music & Home Entertainment Oct. 8, 1983 $3 (U.S.) SALE PRICE $150 MIL LAWYERS, MANAGERS COMPLAIN Polytram Seeking New Acts: Labels Play lt Tight By PAUL GREI\ signings is brighter than it :rs during In fixing mechanical payments. Buyer For Chappell and SAM SUTHERLAND the deepest trough of the recession. record companies are now often de- licensing arrange- LOS ANGELES -New artists may There's also general agreement ihat manding a special By IRV EICHTMAN re- be playing a central role in rebuild- de facto artist roster "freezes," in evi- ment whereby songwriting acts NEW YORK -Chappell Music Indications are that PolyGram will ing the record /tape marketplace, but dence as recently as the last quarter ceive only fractional payment of the for and its associated companies are be- not reveal a potential buyer when its most major labels are still hanging of 1982, have now relaxed. 4.25 cents per song fee now called ing put up for sale by the PolyGram announcement is made. Finding a tough in negotiating new artist deals. However, label negotiators now under the provisions of the Copyright Group. purchaser is viewed as a longterm Most attorneys, managers and seek to minimize contractual risks Law of 1976. Most sources say labels Substantiating widespread rumors process, since a general consensus business affairs executives surveyed and contain investments through a seek to hold fees to 75% of the full rate, or just over three throughout the year, official word of holds that sale of Chappell would agree t hat the outlook for new act number of strategics: mechanical PolyGram's intention to divest itself command a selling price of about cents. -

Starr New KDKA'

ISSUE NUMBER 497 THE INDUSTRY'S NEWSPAPER AUGUST 19, 1983 I New N S I D E: Starr KDKA' Station Manager Networks Enjoy Smooth After four years as Program in sales as well. Satellite Transition Manager at WBZ/Boston, Rick KDKA VP/GM Dan Friel Jr. Starr has returned to Group W commented, "I'm delighted to As radio networks gradually eliminate land - sister station KDKA/Pittsburgh have Rick here. It's a good line service and go all -satellite delivery, in the newly-created position of move for KDKA, because it they're pleased to report widespread Station Manager. Starr, who gives us an opportunity to grow previously served three years broadcaster acceptance of a new way of as far as personnel is concern- at KDKA as Executive Produc- radio life. Page 4 ed. We're glad he's back in er and later as Program Man- Pittsburgh " The Case Of The ager, had for the last month Prior to joining Group W, been helping KDKA set up its Starr programmed WCAS/ Missing Diaries new morning show hosted by Cambridge, MA for four years. new Arbitron suffered an average decline of John Cigna. In his ca- He told R&R, "This was a very pacity, Starr will supervise 20% in returned usable diaries in the spr- difficult derision to make, as KDKA's programming, promo- great. ing sweep, and the company isn't exactly my life in Boston was so tional and engineering opera- It's tough to leave it all behind. sure why. Jhan Hiber explores the issue tions, and will eventually assist On the other side, KDKA is one on low dia- and focuses how exceptionally of America's great radio sta- ry returns affected Orlando, Providence, tions, and it's a great manage- and Riverside.