Linguistics 107—Intro to Indo-European

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Intramorphological Meanings of Thematic Vowels in Italian Verbs

Sede Amministrativa: Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN: Scienze Linguistiche, Filologiche e Letterarie INDIRIZZO: Linguistica CICLO: XXIV The Intramorphological Meanings of Thematic Vowels in Italian Verbs Direttore della Scuola: Ch.ma Prof. Rosanna Benacchio Coordinatore d’indirizzo: Ch.mo Prof. Gianluigi Borgato Supervisore: Ch.ma Prof. Laura Vanelli Dottoranda: Martina Da Tos Abstract Italian verbs are traditionally classified into three major classes called ‗conjugations‘. Membership of a verb in one of the conjugations rests on the phonological content of the vowel occurring after the verbal root in some (but not all) word forms of the paradigm. This vowel is called ‗thematic vowel‘. The main feature that has been attributed to thematic vowels throughout morphological literature is that they do not behave as classical Saussurean signs in that lack any meaning whatsoever. This work develops the claim that the thematic vowels of Italian verbs are, in fact, Saussurean signs in that they can be attributed a ‗meaning‘ (‗signatum‘), or even more than one (‗signata‘). But the meanings that will be appealed to are somehow different from those which have traditionally been attributed to other morphological units, be they stems or endings: in particular, these meanings would not be relevant to the interpretation of a word form; rather, they would be relevant at the ‗purely morphological‘ (‗morphomic‘, in Aronoff‘s (1994) terms) level of linguistic analysis. They are thus labelled ‗intramorphological‘, remarking that they serve nothing but the morphological machinery of the language. The recognition of ‗intramorphological signata‘ for linguistic signs strongly supports the claim about the autonomy of morphology within the grammar. -

Sofya Dmitrieva Institute for Linguistic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences Nasal-Infixed Presents and Their Collateral

Sofya Dmitrieva Institute for Linguistic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences Nasal-infixed presents and their collateral aorists in Homeric Greek1 The process of formation of the Greek verbal paradigm is closely related to secondary affixation: new presents are built on present and non-present stems, modifying the grammatical semantics of primary roots (Kuryłowicz 1964). The paper analyses the uses of the Greek verbs derived from the IE present stems of the type R(C1C2)-né/n-R(C3)- or R(C1)-né/n-R(C2)- (LIV) and their collateral aoristic formations attested in the Homeric poems. Indo-European nasal-infixed presents are known to be connected with transitivisation (Meiser 1993; Sihler 1995; Shatskov 2016). It has also been observed that Greek n-infix verbs, along with higher degree of transitivity, demonstrate higher degree of telicity in comparison with the corresponding verbs of the same roots without the nasal infix. This feature had been mentioned in earlier studies, particularly concerning the nasal presents in -ανω (Vendryes 1923; Chantraine 1961), and was recently addressed with regard to other Greek n-presents (Dmitrieva 2017). It should be considered that lexical aspect played a significant role in the earlier periods of Ancient Greek (Moser 2017). Imperfects from telic verbs can often express perfective meaning; the employment of imperfectives "pro perfective" has been discussed in the studies dealing with Homeric aspect. (Napoli 2006: 191). Some nasal preterits could even formally be interpreted either as imperfects or aorists (e.g. ὄρινε, ἔκλινε). These conditions provide a good opportunity to investigate how nasal imperfects correspond with the aorists built to the same roots, taking into account the distribution of usages, structure and completeness of verbal paradigm. -

Sambahsa Mundialect Complete Grammar

Sambahsa Mundialect Complete Grammar Henrique Matheus da Silva Lima Revision: Dr. Olivier Simon Version: !.!9.! IMPORTANT NOTES ABOUT LEGAL ISSUES This grammar is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 license. You are free to: Share – copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format Adapt – remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially. You must give appropriate credit, provide a lin to the license, and indicate if changes !ere made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any !ay that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. "ere is the lin for more information# https#$$creativecommons.org$licenses$by$4.0$deed.en %or the elaboration of this grammar, The Grammar Of Sambahsa-Mundialect In English by &r. 'livier (imon !as used. (ome subchapters of this grammar are practically a transcription of 'livier)s book. &r. (imon has given me permission to do so, even considering the license of this book. *)ve also utilized many examples from The Grammar Of Sambahsa-Mundialect In English and others that Dr. Simon made for me. *t)s very important to inform the reader that the language it!elf ! not under a "reat #e "o$$on! l %en!e or anyth ng l ke that, the language is under the traditional Copyright license in !hich &r. 'livier (imon has all property rights. But the language ! free, you can translate your !orks or produce original !orks !ithout the need of &r. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Supplemental Information 1: System Assumptions

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Lab on a Chip This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011 Supplemental Information 1: System Assumptions Starting from the mass transfer equation: ∂C 2 + υ ⋅ ∇C = D∇ C + R ∂t (a) Distance between the droplet and air channels, O(10‐4) m is much smaller than the distance between the droplet channel PDMS device boundary O(10‐2) m, so little € mass transfer is out of the device and most mass transfer is into the air channel. (b) Assume the oil provides no resistance as compared to the PDMS. (c) Assume psuedo‐steady state since the PDMS boundaries and concentration boundary conditions are fixed: ∂C = 0 ∂t (d) No convection € υ = 0 (e) No reaction € R = 0 (f) Since the oil provides little resistance to mass transfer, the end of the droplets can be assumes as a constant value with surface area equal to the height of the droplet, h, multiplied by the width of the droplet (g) The concentration out the top is a function of the distance between droplet and air channels and will related to mass transfer out the sides for fixed droplet/air separations. This mass transfer can be represented by multiplying by an effective area. Therefore the system is simplified to one dimension. ∂ 2C = 0 ∂x 2 BC1 C(x = 0) = Csat,PDMS € Csat,PDMS BC2 C(x = d) = Cair = HCair Csat,air € (Csat,PDMS − HCair ) C = Csat,PDMS − x d € dC C − HC J = −D = D ( sat,PDMS air ) dx d € € Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Lab on a Chip This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011 Supplemental Information 2: Droplet Change This derivation and model is derived assuming an approximate rectangular block shaped droplet with constant fluxes (Jtop, Jend, Jside) out of each the top, the ends and the side of the drop (Atop, Aend, Aside) in Equation S1. -

Ablaut and the Latin Verb

Ablaut and the Latin Verb Aspects of Morphophonological Change Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München vorgelegt von Ville Leppänen aus Tampere, Finnland München 2019 Parentibus Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Olav Hackstein (München) Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Gerhard Meiser (Halle) Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 17. Mai 2018 ii Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. vii List of abbreviations and symbols ........................................................................................... viii 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1. Scope, aim, theory, data, and method ............................................................................. 2 1.2. Previous research ............................................................................................................. 7 1.3. Terminology and definitions ......................................................................................... 12 1.4. Ablaut ............................................................................................................................ 14 2. Verb forms and formations .................................................................................................. 17 2.1. Verb systems overview ................................................................................................ -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Indo-European Linguistics: an Introduction Indo-European Linguistics an Introduction

This page intentionally left blank Indo-European Linguistics The Indo-European language family comprises several hun- dred languages and dialects, including most of those spoken in Europe, and south, south-west and central Asia. Spoken by an estimated 3 billion people, it has the largest number of native speakers in the world today. This textbook provides an accessible introduction to the study of the Indo-European proto-language. It clearly sets out the methods for relating the languages to one another, presents an engaging discussion of the current debates and controversies concerning their clas- sification, and offers sample problems and suggestions for how to solve them. Complete with a comprehensive glossary, almost 100 tables in which language data and examples are clearly laid out, suggestions for further reading, discussion points and a range of exercises, this text will be an essential toolkit for all those studying historical linguistics, language typology and the Indo-European proto-language for the first time. james clackson is Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge, and is Fellow and Direc- tor of Studies, Jesus College, University of Cambridge. His previous books include The Linguistic Relationship between Armenian and Greek (1994) and Indo-European Word For- mation (co-edited with Birgit Anette Olson, 2004). CAMBRIDGE TEXTBOOKS IN LINGUISTICS General editors: p. austin, j. bresnan, b. comrie, s. crain, w. dressler, c. ewen, r. lass, d. lightfoot, k. rice, i. roberts, s. romaine, n. v. smith Indo-European Linguistics An Introduction In this series: j. allwood, l.-g. anderson and o.¨ dahl Logic in Linguistics d. -

„Lydian: Late Hittite Or Neo-Luwian?“ Ladies and Gentlemen! the Language of Ancient Lydia Has Raised Unsolvable Questions for Languages Histo- Rians for a Long Time

„Lydian: Late Hittite or Neo-Luwian?“ Ladies and gentlemen! The language of ancient Lydia has raised unsolvable questions for languages histo- rians for a long time. It is therefore no coincidence that the number of publications on Lydian is only a fraction of the publications on the other Indo-European langu- ages of Anatolia. Now a trend reversal seems to be apparent: At the conference „Licia e Lidia prima dellØ ellenizzazioneı (Lycia and Lydia before the Hellenizati- on) held in Rome in august 1988 two lectures treated the todays subject: the question where Lydian is to be placed within the languages of ancient Anatolia. It is not surprising that Lydian is moving into the center of interest. For in recent years the historical investigation of the Anatolian languages has made great pro- gress. This puts us into a better position to tackle the question of Lydian and its origins again. Particularly I want to stress one fact that has become clear in recent years. We now know that several Anatolian languages share significant linguistic features and can therefore be taken as a dialectal subgroup of the Anatolian langua- ge tree (1). This subgroup is termed „Luwianı. This Luwian subgroup comprises … o … first Cuneiform Luwian from the 16th to the 13th century B.C. o … second Hieroglyphic Luwian as a link between the second and the first millennium B.C. o … third the Neo-Luwian languages Carian, Lycian, Mylian, Sidetic and Pi- sidian. These Neo-Luwian languages are attested from the middle of the se- venth century B.C. to the third century B.C. -

Sanskrit-Slavic-Sinitic Their Common Linguistic Heritage © 2017 IJSR Received: 14-09-2017 Milorad Ivankovic Accepted: 15-10-2017

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2017; 3(6): 70-75 International Journal of Sanskrit Research2015; 1(3):07-12 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2017; 3(6): 70-75 Sanskrit-Slavic-Sinitic their common linguistic heritage © 2017 IJSR www.anantaajournal.com Received: 14-09-2017 Milorad Ivankovic Accepted: 15-10-2017 Milorad Ivankovic Abstract Omladinski trg 6/4, SRB-26300 Though viewing from the modern perspective they seem to belong to very distant and alien traditions, the Vrsac, Serbia Aryans, the Slavs and the Chinese share the same linguistic and cultural heritage. They are the only three cultures that have developed and preserved the religio-philosophical concept of Integral Dualism, viz. ś ukram-kr̥ sṇ aṃ or yang-yin (see Note 1). And the existing linguistic data firmly supports the above thesis. Key Words: l-forms, l-formant, l-participles, ping, apple, kolo Introduction In spite of persistent skepticism among so called Proto-Indo-Europeanists, in recent years many scholars made attempts at detecting the genetic relationship between Old Chinese and Proto-Indo-European languages (e.g. T.T. Chang, R.S. Bauer, J.X. Zhou, J.L. Wei, etc.), but they proposed solely lexical correspondences with no morphological ones at all. However, there indeed exist some very important morphological correspondences too. The L-Forms in Chinese In Modern Standard Mandarin Chinese there is a particle spelled le and a verb spelled liao, both functioning as verb-suffixes and represented in writing by identical characters. Some researchers hold that the particle le actually derived from liao since “the verb liao (meaning “to finish, complete”), found at the end of the Eastern Han (25-220 CE) and onwards, around Wei and Jin Dynasties (220-581 CE) along with other verbs meaning “to finish” such as jing, qi, yi and bi started to occur in the form Verb (Object) + completive to indicate the completion of the action indicated by the main verb. -

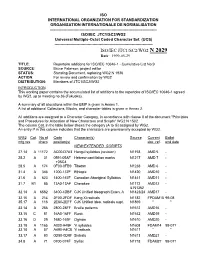

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29

ISO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29 TITLE: Repertoire additions for ISO/IEC 10646-1 - Cumulative List No.9 SOURCE: Bruce Paterson, project editor STATUS: Standing Document, replacing WG2 N 1936 ACTION: For review and confirmation by WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of JTC1/SC2/WG2 INTRODUCTION This working paper contains the accumulated list of additions to the repertoire of ISO/IEC 10646-1 agreed by WG2, up to meeting no.36 (Fukuoka). A summary of all allocations within the BMP is given in Annex 1. A list of additional Collections, Blocks, and character tables is given in Annex 2. All additions are assigned to a Character Category, in accordance with clause II of the document "Principles and Procedures for Allocation of New Characters and Scripts" WG2 N 1502. The column Cat. in the table below shows the category (A to G) assigned by WG2. An entry P in this column indicates that the characters are provisionally accepted by WG2. WG2 Cat. No of Code Character(s) Source Current Ballot mtg.res chars position(s) doc. ref. end date NEW/EXTENDED SCRIPTS 27.14 A 11172 AC00-D7A3 Hangul syllables (revision) N1158 AMD 5 - 28.2 A 31 0591-05AF Hebrew cantillation marks N1217 AMD 7 - +05C4 28.5 A 174 0F00-0FB9 Tibetan N1238 AMD 6 - 31.4 A 346 1200-137F Ethiopic N1420 AMD10 - 31.6 A 623 1400-167F Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics N1441 AMD11 - 31.7 B1 85 13A0-13AF Cherokee N1172 AMD12 - & N1362 32.14 A 6582 3400-4DBF CJK Unified Ideograph Exten. -

1 Introduction 2 Background L2/15-023

Title: Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Tocharian Script Author: Lee Wilson ([email protected]) Date: 2015-01-26 1 Introduction Tocharian is a Brahmi-based script historically used to write the Tocharian languages (ISO 639-3: xto, txb), traditionally referred to as Tocharian A and Tocharian B, which belong to the Tocharian branch of the Indo-European language family. The script was in use primarily during the 8th century CE by the people inhabiting the northern edge of the Tarim Basin of the Taklamakan Desert in what is now Xinjiang in western China, an area formerly known as Turkestan. The Tocharian script is attested in over 4,000 extant manuscripts that were discovered in the early 20th century in the Tarim Basin. The discovery was significant for two reasons: first, it revealed a previously unknown branch of the Indo-European language family, and second, it marked the easternmost geographical extent of that language family. The most distinctive aspect of Tocharian script is the vowel transcribed as ä, commonly known as the Fremdvokal, and the modifications to the script that it entails. This vowel is indicated with a vowel sign not employed in scripts outside of the Tarim Basin region. However, this vowel sign is not commonly used when writing Tocharian. Instead, sequences of a consonant followed by the Fremdvokal are most typically indicated by 11 CV signs known as Fremdzeichen, which are unique to Tocharian. 2 Background The Tocharian script is a north-eastern descendant of Brahmi script, related to Khotanese, Tibetan, and Siddham scripts, which was used along the Tarim Basin in the Taklamakan Desert in what is now Xinjiang in western China.