Philadelphia Mural Arts Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fy21 Proposed Budget

CITY OF PHILADELPHIA ORGANIZATION CHART (ALL FUNDS) BY PROGRAM FISCAL 2021 OPERATING BUDGET Department No. Mural Arts Program 50 Managing Directors Office Mural Arts Program Director 12 Jane Golden-Heriza 10 01 SECTION 7 Mural Arts Program 12 10 FY21 PROPOSED BUDGET ORGANIZATION FY20 FY21 FILLED BUDGETED 1 POS. 11/19 POSITIONS 71-53A (Program Based Budgeting Version) CITY OF PHILADELPHIA DEPARTMENTAL SUMMARY BY FUND FISCAL 2021 OPERATING BUDGET Department No. Mural Arts Program 50 Fiscal 2019 Fiscal 2020 Fiscal 2020 Fiscal 2021 Increase Actual Original Estimated Proposed or No. Fund Class Description Obligations Appropriation Obligations Budget (Decrease) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) 01 100 Employee Compensation a) Personal Services 587,931 638,987 649,569 578,952 (70,617) b) Employee Benefits 200 Purchase of Services 1,779,296 1,860,615 1,895,615 1,425,610 (470,005) General 300 Materials and Supplies 400 Equipment 500 Contributions, etc. 800 Payments to Other Funds Total 2,367,227 2,499,602 2,545,184 2,004,562 (540,622) 100 Employee Compensation a) Personal Services b) Employee Benefits 200 Purchase of Services 300 Materials and Supplies 400 Equipment 500 Contributions, etc. 800 Payments to Other Funds Total 100 Employee Compensation a) Personal Services b) Employee Benefits 200 Purchase of Services 300 Materials and Supplies 400 Equipment 500 Contributions, etc. 800 Payments to Other Funds Total 100 Employee Compensation a) Personal Services b) Employee Benefits 200 Purchase of Services 300 Materials and Supplies 400 Equipment 500 Contributions, etc. 800 Payments to Other Funds Total 100 Employee Compensation a) Personal Services b) Employee Benefits 200 Purchase of Services 300 Materials and Supplies 400 Equipment 500 Contributions, etc. -

Making Exact Change

Making Exact Change How U.S. arts-based programs have made a significant and sustained impact on their communities A Research Project of the Community Arts Network By William Cleveland, the Center for the Study of Art and Community Published by Art in the Public Interest November 2005 Making Exact Change How U.S. arts-based programs have made a significant and sustained positive impact on their communities © 2005 Art in the Public Interest ART IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST promotes information exchange, research and critical dialogue within the field of community-based arts. Its primary program is the Community Arts Network (CAN). http://www.communityarts.net Art in the Public Interest Linda Frye Burnham & Steven Durland, co-directors P.O. Box 68, Saxapahaw, NC 27340 This report is also available on the Web at: http://www.makingexactchange.org On the cover: Detail of a Village of Arts and Humanities mural project. Photo courtesy the Village of Arts and Humanities 4 Making Exact Change Making Exact Change Table of Contents Part One: Introduction . 6 Part Two: Case Studies . .11 CityKids . .12 GRACE (Grass Roots Art and Community Effort) . .21 Isangmahal Arts Kollective . .29 Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild . .36 Mural Arts Program . .47 Northern Lakes Center for the Arts . .55 Swamp Gravy . .64 Village of Arts and Humanities . .73 Wing Luke Asian Museum . .83 Zuni-Appalachian Exchange and Collaboration . .93 Part Three: Findings . .102 Part Four: Recommendations . .122 End Notes . .132 Appendices Appendix A: Request for Study Subjects . .134 Appendix B: Questions for Study Sites . .136 Project Personnel . .139 Making Exact Change 5 Introduction Part One Introduction In 1976, U.S. -

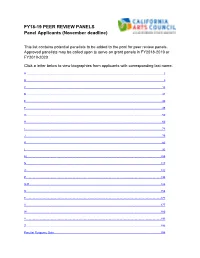

Panel Pool 2

FY18-19 PEER REVIEW PANELS Panel Applicants (November deadline) This list contains potential panelists to be added to the pool for peer review panels. Approved panelists may be called upon to serve on grant panels in FY2018-2019 or FY2019-2020. Click a letter below to view biographies from applicants with corresponding last name. A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 C ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18 D ............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 E ............................................................................................................................................................................. 40 F ............................................................................................................................................................................. 45 G ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

School of Art 2016–2017

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Art 2016–2017 School of Art 2016–2017 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 1 May 15, 2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 1 May 15, 2016 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility Full Text Edited by Paula Marincola

QUESTIONS OF PRACTICE Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility Full Text Edited by Paula Marincola THE PEW CENTER FOR ARTS & HERITAGE / PCAH.US / @PEWCENTER_ARTS CURATING NOW: IMAGINATIVE PRACTICE/PUBLIC RESPONSIBILITY OCT 14-15 2000 Paula Marincola Robert Storr Symposium Co-organizers Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative Funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts Administered by The University of the Arts The Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative is a granting program funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and administered by The University of the Arts, Philadelphia, that supports exhibitions and accompanying publications.“Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility” has been supported in part by the Pew Fellowships in the Arts’Artists and Scholars Program. Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative 230 South Broad Street, Suite 1003 Philadelphia, PA 19102 215-985-1254 [email protected] www.philexin.org ©2001 Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative All rights reserved ISBN 0-9708346-0-8 Library of Congress catalog card no. 2001 131118 Book design: Gallini Hemmann, Inc., Philadelphia Copy editing: Gerald Zeigerman Printing: CRW Graphics Photography: Michael O’Reilly Symposium and publication coordination: Alex Baker CONTENTS v Preface Marian Godfrey vii Introduction and Acknowledgments Paula Marincola SATURDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2000 AM 3 How We Do What We Do. And How We Don’t Robert Storr 23 Panel Statements and Discussion Paul Schimmel, Mari-Carmen Ramirez, Hans-Ulrich Obrist,Thelma Golden 47 Audience Question and Answer SATURDAY, -

Asian Arts Initiative What We Want Is Here: Neighbor Hood

WHAT WE WANT IS HERE: WE WANT WHAT WHAT WE WANT IS NEIGHBORHOOD PROJECTS 2012–2018 NEIGHBORHOOD PROJECTS HERE: NEIGHBOR HOOD PROJECTS 2012—2018 ASIAN ARTS INITIATIVE ARTS ASIAN ASIAN ARTS INITIATIVE CONTENTS Timeline PEARL STREET PROJECT 6 61 Introduction Gayle Isa 9 Advice From the Field 68 Towards Synergy and Transformation: Reflections on Arts and Cultural Organizations as Allies in Community Development and Planning Contributor Biographies Maria Rosario Jackson, Ph.D. 12 72 Poetics and Praxis of a City in Relation Roberto Bedoya 15 STAFF & BOARD 77 The Joy We Make: Culture and Relationships in Funders Urban Planning and Design Theresa Hwang 21 78 Social Practice Lab 50 Credits 80 2 Asian Arts Initiative 3 What We Want Is Here: Neighborhood Projects 2012—2018 TIMELINE 2012 AAI launches two new neigh- borhood programs, the Social Practice Lab Artist Residency, 2014 1997 AAI issues the first open call AAI moves out of Painted and the Pearl Street Project. Bride Art Center and into to artists and neighborhood the Gilbert Building at 1315 2005 members for Pearl Street Cherry Street. Our first Chinatown Micro-Projects, which are 2016– In/flux exhibition opens scheduled throughout the with a community block next year. party and walking tours of 2018 Guided by a Working Group 7 contemporary artists’ 2013 of diverse neighborhood projects installed throughout 1993 AAI celebrates the culmina- stakeholders, Asian Arts the neighborhood. Asian Arts Initiative (AAI) 2000 tion of the inaugural cohort Initiative publishes the is created at Painted Bride AAI’s Gallery program is of Social Practice Lab Artist generated by a group of People:Power:Place cultural Art Center in response to Residencies, and throws the plan and prepares to pilot community concerns about volunteers who install track first of many Pearl Street the Shared Spaces 共享空間 racial tension. -

Camille Billops and James V. Hatch Archives at Emory University

Camille Billops and James V. Hatch archives at Emory University Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Digital Material Available in this Collection Descriptive Summary Title: Camille Billops and James V. Hatch archives at Emory University Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 927 Extent: 47.25 linear feet (95 boxes), 12 oversized papers boxes and 16 oversized papers folders (OP), 6 extra oversized papers (XOP), AV Masters: 9.25 linear feet (9 boxes and LP1-4), and 10 GB born digital material (231 files) Abstract: The Camille Billops and James Hatch Archives at Emory University consists of a variety of materials relating to African American culture and art. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special Restrictions: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance for access to this material. Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Please note that some of the items in this collection are copies of materials held in other archival repositories. The Library will not provide researchers with copies of those items. Researchers wishing to obtain copies of these materials should contact the repository that owns the originals. Related Materials in Other Repositories Hatch-Billops Oral History at the City College of New York Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

Spring 2013 Art Works Grant Announcement

National Endowment for the Arts — 2013 Spring Grant Announcement Art Works Discipline/Field Listings Project details are as of April 23, 2013. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Art Works grants supports the creation of art that meets the highest standards of excellence, public engagement with diverse and excellent art, lifelong learning in the arts, and the strengthening of communities through the arts. Click the discipline/field below to jump to that area of the document. Arts Education Dance Design Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Endowment approval. Page 1 of 130 Arts Education Number of Grants: 103 Total Dollar Amount: $3,870,000 826 Boston, Inc. $20,000 Roxbury, MA To support Young Authors Book Program, an in-school literary arts program. Underserved high school students will receive one-on-one instruction from trained writers who will help them write, edit, and polish their work, which will be published in a professionally designed book. As many as 60 students, 5 writers, and 3 teachers will participate in the project. 826 Seattle $35,000 Seattle, WA To support Creating a Community of Young Authors, a free writing program. Project activities include writing workshops, field trips, student performances, and publication of student work. Alameda County Office of Education (aka Alliance for Arts Learning Leadership) $25,000 Hayward, CA To support professional development for whole-school arts integration at middle schools in Alameda County, California. -

San Francisco Arts Commission Mural Design Information Form LEAD

San Francisco Arts Commission Mural Design Information Form LEAD ARTIST Sorell Tsui ADDRESS 3567 Lakeshore Ave. CITY STATE ZIP CODE Oakland, CA 94610 EMAIL [email protected] PHONE 510-565-0121 PROJECT COORDINATOR Erika Gee, Chinatown CCDC ADDRESS 1525 Grant Ave. CITY STATE ZIP CODE San Francisco, CA 94133 EMAIL [email protected] PHONE 415-984-1497 SPONSORING ORGANIZATION Chinatown Community Development Center ADDRESS 1525 Grant Ave. CITY STATE ZIP CODE San Francisco, CA 94133 EMAIL [email protected] PHONE 415-984-1497 FUNDING SOURCES Community Challenge Grant PROPOSED SITE (address, cross street ) 1201 Powell St (at Jackson), San Francisco, CA 941311 DISTRICT 3 MURAL TITLE: Chinese Pattern and Landscape Mural DIMENSIONS Left panel: 45 ft. height x 21 ft. width Right panel: 48 ft. height x 18 ft. 6 inches width. ESTIMATED SCHEDULE (start and completion dates) start June 1, 2021, end July 1, 2021 1. Proposal (describe proposed design, site and theme. Attach a separate document if needed). The mural design includes a California coastal landscape that has a Chinese feel. We have a strip of separation with a cloud design from the stone gate in the park. We believe incorporating design elements from the history of the park will add a cohesive element to the design that honors the past, while envisioning a future. This is an example of the concept in our mural design. We have included floral patterns with a jade background for the majority of the mural. We will use complimentary colors to highlight the landscape. 2. Materials and processes to be used for wall preparation, mural creation and anti-graffiti treatment. -

Mural Arts Program Revised Fiscal Year 2021 Budget

MURAL ARTS PROGRAM MURAL ARTS PROGRAM REVISED FISCAL YEAR 2021 BUDGET TESTIMONY The revised FY21 Budget and FY21-25 Plan focuses on providing core services and targeting reductions to areas with the least impact on vulnerable populations and areas where others can fund or deliver services. DEPARTMENT FUNDING LEVELS General Fund Financial Summary by Class FY21 Original FY21 $ Difference FY20 Original FY20 Estimated Proposed Revised Proposed Original to Appropriations Obligations Appropriations Appropriations Revised Proposed Class 100 - Employee $638,987 $649,569 $597,069 $578,852 ($18,217) Compensation Class 200 - Purchase of $1,860,615 $1,895,615 $1,913,115 $1,425,610 ($487,505) Services $2,499,602 $2,545,184 $2,510,184 $2,004,562 ($505,722) GENERAL FUND FULL-TIME POSITIONS General Fund Full-Time Positions FY21 Difference FY20 Adopted November 2019 FY21 Original Revised Proposed Original to Budget Increment Run Proposed Budget Budget Revised Proposed Full-Time 12 12 11 10 (1) Positions Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Testimony 1 MURAL ARTS PROGRAM MURAL ARTS PROGRAM ORIGINAL FISCAL YEAR 2021 BUDGET TESTIMONY This testimony was prepared by the Mural Arts Program after the onset of COVID-19 and its impact on City government operations. It reflects the revised proposed FY21 budget and the department’s new operational plan. Additional post COVID-19 responses from the Department are listed in the next section. DEPARTMENT MISSION & PLANS Mission: Through participatory public art, Mural Arts Philadelphia inspires change in people, place, and practice, creating opportunity for a more just and equitable Philadelphia. Mural Arts Philadelphia envisions a world where all people have a say in the future of their lives and communities; where art and creative practice are respected as critical to sense of self and place; and where cultural vibrancy reflects and honors all human identities and experiences. -

A Review on Graffiti Phenomenon: a Study Around Jakarta Indonesia

International Journal of u- and e- Service, Science and Technology Vol.10, No.8 (2017), pp.183-198 http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/ijunesst.2017.10.8.17 A Review on Graffiti Phenomenon: A Study around Jakarta Indonesia Bambang Winarso Universitas Prof. Dr. Moestopo (Beragama) Jl. Hang Lekir I No. 8, Senayan, Jakarta 10270, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract Graffiti is often regarded as a form of social disruption and symbol of disorder in a region. This phenomenon is growing in many urban areas around the world. This paper aims to provide a social overview of graffiti phenomenon occurring in developing countries such as Indonesia, especially in urban areas of Jakarta. Through a qualitative approach, a review is obtained that the graffiti phenomenon in Jakarta is more likely a manifestation of existence of the graffiti actors both by individuals and groups in the social environment where they thrive. On the other hand, the social environment includes the people who tend to neglect and are lack of responsiveness in capturing the symbolic interaction emerged from the graffiti phenomenon. Keywords: Graffiti; Social environment; Symbolic interaction; Urban phenomenon; Vandalism 1. Introduction Historically, graffiti has been used by experts to reconstruct the history of Pompeii and Ancient Greek society [1]. According to Alonso in [1], graffiti is defined as small scratches derived from Italian graffiare which means scratches. For thousands of years ancient cultures have known this kind of literature expression. Therefore, according to Alonso in [1] graffiti can help unlock a unique insight into the society. However, nowadays, graffiti is more precisely defined as an act of vandalism that damages the property of others. -

PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA Mural Arts Program Engages Community Members in Murals That Improve Aesthetics and Transform Neighborhoods

PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA Mural Arts Program engages community members in murals that improve aesthetics and transform neighborhoods “Murals work on a symbolic level, providing opportunities for communities to express concerns, values, and aspirations: their yearning to be free of violence and fear; their hope to create a better world for themselves and their children; their desire to remember those who were overcome or who overcame...They are our dreams manifest.” —JANE GOLDEN, DIRECTOR MURAL ARTS PROJECT, FOREWORD PHILADELPHIA MURALS AND THE STORIES THEY TELL PHILADELPHIA MURALS AND THE STORIES THEY TELL PHILADELPHIA MURALS AND THE STORIES IN SECRET BOOK, 1999. ervent in the belief that public art has the power support civic pride. MAP is responsible for the creation F to eradicate urban blight and create community of over 2000 murals since the mid 1980’s.1 change, Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program (MAP) fol- lows a community participatory model to transform THE PLACE graffiti-scarred walls into scenic views in diverse neigh- borhoods citywide. In the process of creating murals MAP operates primarily in low-income neighbor- that feature portraits of community heroes, tell neigh- hoods across Philadelphia, reaching residents of all races borhood stories or display abstract designs, MAP fos- and ethnicities. As the popularity of murals increases ters connections among neighbors and word spreads, murals are now and forges new bonds between res- being created in wealthier neigh- idents (including at-risk youth), borhoods, as well. During the first “People have an intuitive desire professional artists, and mural fun- five years of the program, murals to have art around, and murals ders.