Title of Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Inclusion Initiative

Economy Neighborhood Research Education Civic Quality of Life Healthcare Social Services Safety Community Culture Workforce Innovation Impact UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Powering Philadelphia and Pennsylvania Know Penn’s Numbers WHAT IS PENN’S ECONOMIC IMPACT ON PENNSYLVANIA AND ON PHILADELPHIA? Economic impact on Direct, indirect and Pennsylvania and Philadelphia1 induced jobs2 $14.3 billion 90,400 $10.8 billion 68,500 $ Annual tax revenue3 $272 million $197 million 1 All data in this report is from Fiscal Year 2015, unless Direct: Jobs from Penn’s payroll. otherwise noted. Indirect: Jobs created by vendors, suppliers, and 2 Every dollar spent creates a multiplier effect as Penn’s companies who have contracts with Penn, and who own employees spend their earnings in Philadelphia hire staff to service those contracts. and Pennsylvania. Similarly, Penn’s vendors, suppliers, Induced: Jobs created within the larger economy and contractors meet the demand of their contracts with resulting from Penn’s direct spending on wages and Penn by adding jobs and providing supplies, which services that leads to additional spending by individual in turn creates more earning and spending. Together workers and companies. these are categories of defined economic activity known 3 Categories of tax revenue include earned income, as direct, indirect, and induced. business, sales and use, real estate and others. Powering Philadelphia and Pennsylvania THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA FISCAL YEAR 2015 “The University of Pennsylvania and its Health System are an innovating force for good in Philadelphia, our region, society and the world: advancing creative knowledge, making impactful discoveries, sustaining health and educating great new leaders. -

Fy21 Proposed Budget

CITY OF PHILADELPHIA ORGANIZATION CHART (ALL FUNDS) BY PROGRAM FISCAL 2021 OPERATING BUDGET Department No. Mural Arts Program 50 Managing Directors Office Mural Arts Program Director 12 Jane Golden-Heriza 10 01 SECTION 7 Mural Arts Program 12 10 FY21 PROPOSED BUDGET ORGANIZATION FY20 FY21 FILLED BUDGETED 1 POS. 11/19 POSITIONS 71-53A (Program Based Budgeting Version) CITY OF PHILADELPHIA DEPARTMENTAL SUMMARY BY FUND FISCAL 2021 OPERATING BUDGET Department No. Mural Arts Program 50 Fiscal 2019 Fiscal 2020 Fiscal 2020 Fiscal 2021 Increase Actual Original Estimated Proposed or No. Fund Class Description Obligations Appropriation Obligations Budget (Decrease) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) 01 100 Employee Compensation a) Personal Services 587,931 638,987 649,569 578,952 (70,617) b) Employee Benefits 200 Purchase of Services 1,779,296 1,860,615 1,895,615 1,425,610 (470,005) General 300 Materials and Supplies 400 Equipment 500 Contributions, etc. 800 Payments to Other Funds Total 2,367,227 2,499,602 2,545,184 2,004,562 (540,622) 100 Employee Compensation a) Personal Services b) Employee Benefits 200 Purchase of Services 300 Materials and Supplies 400 Equipment 500 Contributions, etc. 800 Payments to Other Funds Total 100 Employee Compensation a) Personal Services b) Employee Benefits 200 Purchase of Services 300 Materials and Supplies 400 Equipment 500 Contributions, etc. 800 Payments to Other Funds Total 100 Employee Compensation a) Personal Services b) Employee Benefits 200 Purchase of Services 300 Materials and Supplies 400 Equipment 500 Contributions, etc. 800 Payments to Other Funds Total 100 Employee Compensation a) Personal Services b) Employee Benefits 200 Purchase of Services 300 Materials and Supplies 400 Equipment 500 Contributions, etc. -

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’S Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’s Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David W. Young Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Steven Conn, Advisor Saul Cornell David Steigerwald Copyright by David W. Young 2009 Abstract This dissertation examines how public history and historic preservation have changed during the twentieth century by examining the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1683, Germantown is one of America’s most historic neighborhoods, with resonant landmarks related to the nation’s political, military, industrial, and cultural history. Efforts to preserve the historic sites of the neighborhood have resulted in the presence of fourteen historic sites and house museums, including sites owned by the National Park Service, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the City of Philadelphia. Germantown is also a neighborhood where many of the ills that came to beset many American cities in the twentieth century are easy to spot. The 2000 census showed that one quarter of its citizens live at or below the poverty line. Germantown High School recently made national headlines when students there attacked a popular teacher, causing severe injuries. Many businesses and landmark buildings now stand shuttered in community that no longer can draw on the manufacturing or retail economy it once did. Germantown’s twentieth century has seen remarkably creative approaches to contemporary problems using historic preservation at their core. -

Philadelphia Merchants, Trans-Atlantic Smuggling, and The

Friends in Low Places: Philadelphia Merchants, Trans-Atlantic Smuggling, and the Secret Deals that Saved the American Revolution By Tynan McMullen University of Colorado Boulder History Honors Thesis Defended 3 April 2020 Thesis Advisor Dr. Virginia Anderson, Department of History Defense Committee Dr. Miriam Kadia, Department of History Capt. Justin Colgrove, Department of Naval Science, USMC 1 Introduction Soldiers love to talk. From privates to generals, each soldier has an opinion, a fact, a story they cannot help themselves from telling. In the modern day, we see this in the form of leaked reports to newspapers and controversial interviews on major networks. On 25 May 1775, as the British American colonies braced themselves for war, an “Officer of distinguished Rank” was running his mouth in the Boston Weekly News-Letter. Boasting about the colonial army’s success during the capture of Fort Ticonderoga two weeks prior, this anonymous officer let details slip about a far more concerning issue. The officer remarked that British troops in Boston were preparing to march out to “give us battle” at Cambridge, but despite their need for ammunition “no Powder is to be found there at present” to supply the Massachusetts militia.1 This statement was not hyperbole. When George Washington took over the Continental Army on 15 June, three weeks later, he was shocked at the complete lack of munitions available to his troops. Two days after that, New England militiamen lost the battle of Bunker Hill in agonizing fashion, repelling a superior British force twice only to be forced back on the third assault. -

Making Exact Change

Making Exact Change How U.S. arts-based programs have made a significant and sustained impact on their communities A Research Project of the Community Arts Network By William Cleveland, the Center for the Study of Art and Community Published by Art in the Public Interest November 2005 Making Exact Change How U.S. arts-based programs have made a significant and sustained positive impact on their communities © 2005 Art in the Public Interest ART IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST promotes information exchange, research and critical dialogue within the field of community-based arts. Its primary program is the Community Arts Network (CAN). http://www.communityarts.net Art in the Public Interest Linda Frye Burnham & Steven Durland, co-directors P.O. Box 68, Saxapahaw, NC 27340 This report is also available on the Web at: http://www.makingexactchange.org On the cover: Detail of a Village of Arts and Humanities mural project. Photo courtesy the Village of Arts and Humanities 4 Making Exact Change Making Exact Change Table of Contents Part One: Introduction . 6 Part Two: Case Studies . .11 CityKids . .12 GRACE (Grass Roots Art and Community Effort) . .21 Isangmahal Arts Kollective . .29 Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild . .36 Mural Arts Program . .47 Northern Lakes Center for the Arts . .55 Swamp Gravy . .64 Village of Arts and Humanities . .73 Wing Luke Asian Museum . .83 Zuni-Appalachian Exchange and Collaboration . .93 Part Three: Findings . .102 Part Four: Recommendations . .122 End Notes . .132 Appendices Appendix A: Request for Study Subjects . .134 Appendix B: Questions for Study Sites . .136 Project Personnel . .139 Making Exact Change 5 Introduction Part One Introduction In 1976, U.S. -

Facts & Figures

FACTS & FIGURES Penn faculty and students are researching diseases, educating physicians, and treating patients in over 23 hospitals and mobile clinics around the globe. Serving the World Recent locations for Penn Medicine’s faculty and student outreach include: Argentina, Austria, Botswana, China, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, France, Ghana, Guatemala, India, Malawi, Mali, the Netherlands, Nicaragua, Poland, Panama, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, United States, Vietnam, and Zambia. Penn Medicine Penn Medicine is among the most prestigious academic medical centers in the world. Its international prominence is built on an ongoing tradition of breakthrough discoveries and innovations, excellence in training tomorrow’s physicians and scientists, and safe and compassionate patient care. In addition to offering the most advanced medical care to our patients, Penn Medicine’s programs and projects extend beyond our institution to vulnerable populations in communities ranging from residents in our own West Philadelphia backyard to those in need around the world. 1 About Penn Medicine Penn Medicine comprises the Perelman School of Medicine and the University of Pennsylvania Health System. Research Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine is consistently among the nation’s top three recipients of federal funding from the National Institutes of Health. Penn’s physicians and scientists focus on research that utilizes an interdisciplinary approach to understand the fundamental mechanisms of disease, leading to new strategies for treatments -

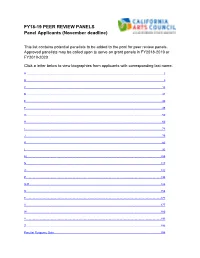

Panel Pool 2

FY18-19 PEER REVIEW PANELS Panel Applicants (November deadline) This list contains potential panelists to be added to the pool for peer review panels. Approved panelists may be called upon to serve on grant panels in FY2018-2019 or FY2019-2020. Click a letter below to view biographies from applicants with corresponding last name. A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 C ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18 D ............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 E ............................................................................................................................................................................. 40 F ............................................................................................................................................................................. 45 G ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

School of Art 2016–2017

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Art 2016–2017 School of Art 2016–2017 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 1 May 15, 2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 1 May 15, 2016 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

Revitalization in Philadelphia, 1940-1970: Rebuilding a City but Straining Race Relations

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2019 May 1st, 9:00 AM - 10:15 AM Revitalization in Philadelphia, 1940-1970: Rebuilding a City but Straining Race Relations Abigail E. Millender Riverdale High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Public History Commons, United States History Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Millender, Abigail E., "Revitalization in Philadelphia, 1940-1970: Rebuilding a City but Straining Race Relations" (2019). Young Historians Conference. 19. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2019/oralpres/19 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Millender 1 Abby Millender Keldorf Global City Period 1 18 February 2019 Revitalization in Philadelphia, 1940-1970: Rebuilding a City but Straining Race Relations Research Question: To what extent did post-World War II revitalization projects in Philadelphia promote segregation in the inner city? Philadelphia is known today for its historical attractions, sports teams, and colonial homes. Tourists can visit the Liberty Bell, Independence Mall, Lincoln Financial Field, and trendy shopping neighborhoods. However, Philadelphia is also known for rundown neighborhoods ridden with violence, poverty, drug abuse, and gang activity. While many large American cities have both affluent and impoverished neighborhoods, Philadelphia’s are a result of and a reminder of its industrial and segregated past. -

Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility Full Text Edited by Paula Marincola

QUESTIONS OF PRACTICE Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility Full Text Edited by Paula Marincola THE PEW CENTER FOR ARTS & HERITAGE / PCAH.US / @PEWCENTER_ARTS CURATING NOW: IMAGINATIVE PRACTICE/PUBLIC RESPONSIBILITY OCT 14-15 2000 Paula Marincola Robert Storr Symposium Co-organizers Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative Funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts Administered by The University of the Arts The Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative is a granting program funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and administered by The University of the Arts, Philadelphia, that supports exhibitions and accompanying publications.“Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility” has been supported in part by the Pew Fellowships in the Arts’Artists and Scholars Program. Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative 230 South Broad Street, Suite 1003 Philadelphia, PA 19102 215-985-1254 [email protected] www.philexin.org ©2001 Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative All rights reserved ISBN 0-9708346-0-8 Library of Congress catalog card no. 2001 131118 Book design: Gallini Hemmann, Inc., Philadelphia Copy editing: Gerald Zeigerman Printing: CRW Graphics Photography: Michael O’Reilly Symposium and publication coordination: Alex Baker CONTENTS v Preface Marian Godfrey vii Introduction and Acknowledgments Paula Marincola SATURDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2000 AM 3 How We Do What We Do. And How We Don’t Robert Storr 23 Panel Statements and Discussion Paul Schimmel, Mari-Carmen Ramirez, Hans-Ulrich Obrist,Thelma Golden 47 Audience Question and Answer SATURDAY, -

Asian Arts Initiative What We Want Is Here: Neighbor Hood

WHAT WE WANT IS HERE: WE WANT WHAT WHAT WE WANT IS NEIGHBORHOOD PROJECTS 2012–2018 NEIGHBORHOOD PROJECTS HERE: NEIGHBOR HOOD PROJECTS 2012—2018 ASIAN ARTS INITIATIVE ARTS ASIAN ASIAN ARTS INITIATIVE CONTENTS Timeline PEARL STREET PROJECT 6 61 Introduction Gayle Isa 9 Advice From the Field 68 Towards Synergy and Transformation: Reflections on Arts and Cultural Organizations as Allies in Community Development and Planning Contributor Biographies Maria Rosario Jackson, Ph.D. 12 72 Poetics and Praxis of a City in Relation Roberto Bedoya 15 STAFF & BOARD 77 The Joy We Make: Culture and Relationships in Funders Urban Planning and Design Theresa Hwang 21 78 Social Practice Lab 50 Credits 80 2 Asian Arts Initiative 3 What We Want Is Here: Neighborhood Projects 2012—2018 TIMELINE 2012 AAI launches two new neigh- borhood programs, the Social Practice Lab Artist Residency, 2014 1997 AAI issues the first open call AAI moves out of Painted and the Pearl Street Project. Bride Art Center and into to artists and neighborhood the Gilbert Building at 1315 2005 members for Pearl Street Cherry Street. Our first Chinatown Micro-Projects, which are 2016– In/flux exhibition opens scheduled throughout the with a community block next year. party and walking tours of 2018 Guided by a Working Group 7 contemporary artists’ 2013 of diverse neighborhood projects installed throughout 1993 AAI celebrates the culmina- stakeholders, Asian Arts the neighborhood. Asian Arts Initiative (AAI) 2000 tion of the inaugural cohort Initiative publishes the is created at Painted Bride AAI’s Gallery program is of Social Practice Lab Artist generated by a group of People:Power:Place cultural Art Center in response to Residencies, and throws the plan and prepares to pilot community concerns about volunteers who install track first of many Pearl Street the Shared Spaces 共享空間 racial tension. -

PHILADELPHIA WOMEN and the PUBLIC SPHERE, 1760S-1840S

“THE YOUNG WOMEN HERE ENJOY A LIBERTY”: PHILADELPHIA WOMEN AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE, 1760s-1840s By KATHARINE DIANE LEE A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Nancy Hewitt and Paul G. E. Clemens And approved by _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “The Young women here enjoy a liberty”: Philadelphia Women and the Public Sphere, 1760s-1840s by KATHARINE DIANE LEE Dissertation Director: Nancy Hewitt This dissertation examines women’s access to and participation in the community life of Philadelphia in the decades surrounding the American Revolution. It argues against the application of separate spheres to late-colonial and early national Philadelphia and proposes that women were heavily integrated into nearly all aspects of the city’s public life. Women from diverse backgrounds were actively involved in commerce, politics, protest, intellectual and legal debates, social institutions, wartime developments, educational advancements, and benevolent causes. They saw themselves and were viewed by their peers as valuable members of a vibrant and complex city life. If we put aside assumptions about women’s limited relationship to the public sphere, we find a society in which women took advantage of a multitude of opportunities for participation and self-expression. This project also examines the disparity between the image of the ideal housewife and the lived experience of the majority of female Philadelphians. Idealized descriptions of Revolutionary women present a far more sheltered range of options than those taken advantage of by most actual women.