The Essay As Art Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Additions 2021 1 / 1

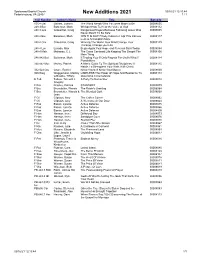

Spotswood Baptist Church 03/16/21 12:10:44 Federicksburg, VA 22407 New Additions 2021 1 / 1 Call Number Author's Name Title Barcode 155.4 Gai Gaines, Joanna The World Needs Who You were Made to Be 00008055 248.3 Bat Batterson, Mark Whisper:How To Hear the Voice of God 00008112 248.3 Gro Groeschel, Craig Dangerous Prayers:Because Following Jesus Was 00008095 Never Meant To Be Safe 248.4 Bat Batterson, Mark WIN THE DAY:7 Daily Habits to Help YOu bStress 00008117 Less & Accomplish More 248.4 Gro Groeschel, Craig Winning The WarIn Your Mind:Change Your 00008129 Thinking, Change your Life 248.4 Luc Lucado, Max Begin Again:Your Hope and Renewal Start Today 00008054 248.4 Mah Mahaney, C.J. The Cross Centered Life:Keeping The Gospel The 00008106 Main Thing 248.842 Bat Batterson, Mark If:Trading Your If Only Regrets For God's What If 00008114 Possibilities 248.842 Mor Morley, Patrick A Man's Guide To The Spiritual Disciplines:12 00008115 Habits To Strengthen Your Walk With Christ 332.024 Cru Cruze, Rachel Know Yourself Know Your Money 00008060 920 Weg Weggemann, Mallory LIMITLESS:The Power Of Hope And Resilience To 00008118 w/Brooks, Tiffany Overcome Circumstance E Teb Tebow, Tim w/A.J. A Party To Remember 00008018 Gregory F Bra Bradley, Patricia STANDOFF 00008079 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda The Robin's Greeting 00008084 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda & The Blended Quilt 00008068 Jean F Cli Clipston, Amy The Coffee Corner 00008062 F Cli Clipston, Amy A Welcome At Our Door 00008064 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active Defense 00008015 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active -

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Mary Henry Pansynclastic Riddle 1966, 48 x 61.5 Courtesy of the Artist and Bryan Ohno Gallery Cover photo: Hilda Morris in her studio 1964 Photo: Hiro Moriyasu Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism Organized by The Art Gym, Marylhurst University 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington with support from the Regional Arts and Culture Council, the Lamb Foundation, members and friends. The Art Gym, Marylhurst University, Marylhurst, Oregon Kathleen Gemberling Adkison September 26 – November 20, 2004 Doris Chase Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner, Washington January 15 – April 3, 2005 Sally Haley Mary Henry Maude Kerns LaVerne Krause Hilda Morris Eunice Parsons Viola Patterson Ruth Penington Amanda Snyder Margaret Tomkins Eunice Parsons Mourning Flower 1969, collage, 26 x 13.5 Collection of the Artist Photo: Robert DiFranco Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Copyright 2004 Marylhurst University Post Offi ce Box 261 17600 Pacifi c Highway Marylhurst, Oregon 97036 503.636.8141 www.marylhurst.edu Artworks copyrighted to the artists. Essays copyrighted to writers Lois Allan and Matthew Kangas. 2 All rights reserved. ISBN 0-914435-44-2 Design: Fancypants Design Preface Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve presented work created prior to 1970. Most of our Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington exhibitions either present art created specifi cally grew out of a conversation with author and for The Art Gym, or are mid-career or retrospective critic Lois Allan. As women, we share a strong surveys of artists in the thick of their careers. -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

Eightvolumesofle03maraiala Bw.Pdf

??ps '\%^ 1 1 , I '• ' ;" * li& J*^ '; . i•'^ fe«&i&~ /^^^^ •' ^ a 1 .\^ W^\ « Drnia 9 ""-'^•--38 al iM -- J J i^- li THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES « ' t . THE Third Volume LETTERS Wri by a Who lived Five and Forty Years, PARIS:Undifcovered, at Giving an Impartial Account to the Divan at Conjlantinofle^ of the moft remarkable Tranfadions of Europe ; and difcovering feveral Intrigues and Secrets of the ChriHinn Courts (efpecially of that of France^ continued from the Year 1645, to the Year 1682. Written Orisrinally in Arabicic, Trmjlatcd into Ita- lian, and from thence into Englifli, by theTrmfla- tor $f thi Firft VOLUME. C(;c €igl;tl) Cmtton. LONDON: Printed for J. Rhodes^ D. B'ovn, R. S^rc, B. and S. Totke, G. Strahan, W. Me'rs, S. Ballard, and F. Clay, 1723. V ^HG r U- 1 T O T H E READER. ^lJ R Arabian^ having met with fo kind Encertainmcnc j in this Nation fince he put cm the Englijh-DrcCSy is refolvei- CO continue his Garb, and vilit you as often as Convenience will, permit. He brings along with him many foreign Commodities, to gratify the various Ex- pedations of People. His Cargo confift- ing of Jewels and other Rarities, which are the genuine Product of theE*/; and fome kinds of Merchandife, which he has purchafed here in the fi'efi, during his Re fide nee at Paris. It will be pity to affront this honeil Stranger, by railing Scandals on him, as if he were a Counterfeit, and 1 know not what. -

Anthems, Sonnets, and Chants

Anthems, Sonnets, and Chants Anthems, Sonnets, and Chants Recovering the African American Poetry of the 1930s JON WOODSON THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2011 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Woodson, Jon. Anthems, sonnets, and chants : recovering the African American poetry of the 1930s / Jon Woodson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1146-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1146-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9245-7 (cd) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Depres- sions—1929—United States. 3. Existentialism in literature. 4. Racism in literature. 5. Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935–1936—Influence. I. Title. PS153.N5W66 2011 811'5209896073—dc22 2010022344 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1146-5) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9245-7) Cover design by Laurence Nozik Text design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 FOR LYNN CUrrIER SMITH WOODSON Contents Acknowledgments ix List of Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression: Three Long Poems 15 Chapter 2 Existential Crisis: The Sonnet and Self-Fashioning in the Black Poetry of the 1930s 69 Chapter 3 “Race War”: African American Poetry on the Italo-Ethiopian War 142 A Concluding Note 190 Appendix: Poems 197 Notes 235 Works Cited 253 Index 271 Acknowledgments My thanks to Dorcas Haller—professor, librarian, and chair of the Library Department at the Community College of Rhode Island—for finding the books that I could not find. -

Your Reading: a Booklist for Junior High and Middle School Students

ED 337 804 CS 213 064 AUTHOR Nilsen, Aileen Pace, Ed. TITLE Your Reading: A Booklist for JuniOr High and Middle School Students. Eighth Edition. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-5940-0; ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 347p.y Prepared by the Committee on the Junior High and Middle School Booklist. For the previous edition, see ED 299 570. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 59400-0015; $12.95 members, $16.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Boots; Junior High Schools; Junior High School Students; *Literature Appreciation; Middle Schools; Reading Interests; Reuding Material Selection; Recreational Reading; Student Interests; *Supplementary Reading Materials IDENTIFIERS Middle School Students ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography for junior high and middle school students describes nearly 1,200 recent books to read for pleasure, for school assignments, or to satisfy curiosity. Books included are divided inco six Lajor sections (the first three contain mostly fiction and biographies): Connections, Understandings, Imaginings, Contemporary Poetry and Short Stories, Books to Help with Schoolwork, and Books Just for You. These major sections have been further subdivided into chapters; e.g. (1) Connecting with Ourselves: Accomplishments and Growing Up; (2) Connecting with Families: Close Relationships; (3) -

The Iconography of Oregon's Twentieth-Century Utopian Myth

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-3-1995 From Promised Lands to Promised Landfill: The Iconography of Oregon's Twentieth-Century Utopian Myth Jeffry Lloyd Uecker Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Uecker, Jeffry Lloyd, "From Promised Lands to Promised Landfill: The Iconography of Oregon's Twentieth- Century Utopian Myth" (1995). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5026. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6902 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Jeffry Lloyd Uecker for the Master of Arts in History were presented May 3, 1995, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: Lisa Andrus-Rivera Representative of the Office of Graduate Studie DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: David A. Johns Department of .L. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY By ont.f!G ~4= .,,K/9S- ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Jeffry Lloyd Uecker for the Master of Arts in History presented May 3, 1995. Title: From Promised Land to Promised Landfill: The Iconography of Oregon's Twentieth-Century Utopian Myth The state of Oregon often has been viewed as a utopia. Figures of speech borrowed from the romantic sublime, biblical pilgrimage, economic boosterism, and millenialist fatalism have been used to characterize it. -

Public Public of Variety a Includes Brochure *This % Friday

CL HQ DU Michael T. Hensley, Outside In Mural In Outside Hensley, T. Michael Esplanade Eastbank Katz Vera the along RIGGA, , Gate Echo , at Central Library Central at , Stair Garden Kirkland, Larry CN ! GL , at the Portland Center for the Performing Arts Performing the for Center Portland the at , Bollards Folly Otani, Valerie Park Waterfront McCall Tom , Shift River Gregoire, Mathieu in the North Park Blocks Park North the in Bao Bao Xi'an & Tung Da as well. as artworks commissioned by other agencies agencies other by commissioned artworks *This brochure includes a variety of public public of variety a includes brochure *This % Friday. through Monday 8:00-6:00, are IL GQ CN Manuel Izquierdo, Izquierdo, Manuel Ilan Averbuch, Ilan Averbuch, Dana LynnLouis, James Carpenter, Portland Building at 1120 SW 5th. Hours 5th. SW 1120 at Building Portland Art Gallery on the second floor of the of floor second the on Gallery Art www.racc.org/publicart or visit the Public the visit or www.racc.org/publicart Terra Incognita to go collection, the about more out Spectral Dome Light Metabolic Shift Metabolic Dreamer leading Percent-for-Art programs.* To find To programs.* Percent-for-Art leading County, and manages one of the country’s the of one manages and County, , Pettygrove Park , Pettygrove , Rose Quarter , Rose Multnomah and Portland of City the for art , Pearl District commissions and maintains public maintains and commissions (RACC) , PCPA Regional Arts & Culture Council Culture & Arts Regional The P ORTLAND C ULTURAL T OURS EN J. Seward Johnson, Allow Me, in Pioneer Courthouse Square. -

Portland Public

Norman Taylor Michihiro Kosuge Patti Warashina Kvinneakt John Buck Continuation City Reflections 1975 bronze Lodge Grass Lee Kelly Fernanda D’Agostino (5 artworks) 2009 bronze 2000 bronze Untitled fountain TRANSIT MALL Murals, fountains, abstract Urban Hydrology 2009 granite 1977 and representational works — many created by local artists A GUIDE TO (12 artworks) stainless steel 2009 carved granite — grace downtown Portland’s Transit Mall (Southwest Fifth and Sixth avenues). Many pieces from the original collection, Tom Hardy Bruce West installed in the 1970s, were resited in 2009 along the new MAX Running Horses Untitled PORTLAND 1986 bronze 1977 light rail and car lanes. At that time, 14 new works were added. SW 6th Ave stainless steel SW Broadway PUBLIC MAX light Artwork Artworks with 20 rail stop multiple pieces N SW College St 18 SW Hall St SW 5th Ave Melvin Schuler ART 19 Thor SW Harrison St 1977 copper on redwood Daniel Duford The Legend of SW Montgomery St Mel Katz the Green Man SW Mill St Daddy Long of Portland Legs James Lee (10 artworks along Malia Jensen 2006 painted Hansen Robert Hanson 5th and 6th) 2009 SW Market St 21 Pile aluminum Talos No. 2 Untitled bronze, cast concrete, SW Clay St 2009 bronze 1977 bronze Bruce Conkle (7 artworks) porcelain enamel Burls Will Be Burls 2009 etched on steel 26 (3 artworks) bronze 2009 bronze, SW Columbia St 22 cast concrete SW Jefferson St 25 SW Madison St 27 23 SW Main St Anne Storrs and 28 almon St Kim Stafford 24 SW S 32 Begin Again Corner 2009 etched granite SW Taylor St 29 33 30 SW -

Composition Studies 39.2 Fall 2011

Composition Studies Department of English Non-prot Org. Clemson University U.S. Postage 801 Strode Tower Paid Clemson SC 29634 Clemson, SC Permit No. 10 volume 39 number 2 number 39 volume studies composition Volume 39,Number 2 Volume Fall 2011 Fall The MLA Supports Your Teaching and Scholarship In 2012, the MLA Annual Convention will be held in Seattle from 5–8 January. We hope you will join us to attend sessions, browse in the exhibit hall, meet and dine with friends and colleagues, The MLA Annual and explore Seattle. Convention 5–8 January 2012 Visit www.mla.org and you can • research career and job market information in Seattle • scan reports and surveys issued by the MLA on job featuring a special market issues, enrollments, evaluating scholarship, focus on Language, and the state of scholarly publishing Literature, and Learning • learn about the MLA’s public outreach activities, including the popular MLA Language Map • download the Academic Workforce Advocacy Kit, The largest gathering of teachers a tool for helping improve conditions for students and scholars in the humanities and teachers now meets in January. Other changes include • read FAQs about MLA style These are some of the activities you support when • new features, including more you become an MLA member. Graduate students may roundtables and workshops join for $20 per year for a maximum of seven years. • more collaboration and discussion MLA Member Benefits • more free time in the evenings The MLA offers members a wide array of benefits, including • special presentations featuring renowned thinkers, artists, and • subscriptions to PMLA, critics in conversation the MLA Newsletter, and Profession • local excursions for registrants • online access to the Job • regular Twitter updates during Information List for ADE and the convention ADFL member departments 2012 members receive reduced • priority convention registration rates and special discounts for • access to searchable lists of members and the 2012 convention in Seattle. -

Leihmaterial Boosey & Hawkes (Für Den Deutschsprachigen Raum)

Leihmaterial Boosey & Hawkes (für den deutschsprachigen Raum) - Stand: Dezember 2009 - Komponist / Titel Instrumentation Komp. / Dauer Adam, Adolph Charles 2 Giselle (David Garforth)B 2(II=picc).2(I,II=corA).2.2-4.2.2cornet.3.1-harp-timp.perc: Ballet-Pantomime en Deux Actes tgl/BD/cyms/SD/bells-strings Si j'etais Roi (AubreyB Winter) 1 - Overture 1.picc.2.2.2-4.0.2crt.31-timp.perc-harp-strings 8' Adams, John S Century Rolls B Solo pft-2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2-3.3.2.0-timp.perc(2): 1997 31' for piano and orchestra vib/xyl/wdbl/marimba/high bongo/glsp- harp-cel-strings 1 Chamber SymphonyB 1(=picc).1.2(I=Ebcl, II=bcl).2(II=dbn)-1.1.1.0-perc: 1992 23' trap set(cowbell/hi-hat cym/SD/pedal BD/ wdbl/2bongos/ 3tom-t/roto toms/tamb/timbale/claves/conga)-keyboard sampler (Yamaha SY-77/SY-99 or Kurzweil K2000/2500)- strings 1.0.1.1.1. For complete technical specifications go to: http://www.earbox.com/tech-guide/eq/ja-cs-eq.htm City Noir B 2009 30' for orchestra S The Death of KlinghofferB S,M,C,T,3Bar,B; chorus(min:24 singers); dancers 1990 140' Opera in two acts 2(I,II=picc).2(II=corA).2(II=bcl).2(II=dbn)-2.2.2.0-perc(1): KAT MIDI mallet controller/timp- 3keyboard samplers-strings(8.8.6.6.4) For complete technical requirements go to: http://www.earbox.com/tech-guide/eq/ja-kling-eq.htm p - Aria of the Falling Body picc.1.2.2.2-2.0.2.0-2 or 3keyboard samplers- 1990 7' for baritone and orchestra strings(8.8.6.6.4) For complete technical requirements go to: http://www.earbox.com/tech-guide/eq/ja-kling-eq.htm p - Bird Aria picc.1.2(II=corA).2(II=bcl).1.dbn-2.0.2.0-2 -

Teaching Writing from a Writer's Point of View. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 422 582 CS 216 474 AUTHOR Hermsen, Terry, Ed.; Fox, Robert, Ed. TITLE Teaching Writing from a Writer's Point of View. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5517-0 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 233p.; Based on a summer writing seminar cosponsored by Wright State University and Ohio Arts Council. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 55170-3050: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Creative Writing; Elementary Secondary Education; Summer Programs; *Writing Attitudes; *Writing Instruction; *Writing Workshops IDENTIFIERS Ohio; Writing Contexts; *Writing Thinking Relationship ABSTRACT Based on a series of successful summer writing institutes, this book presents practical ways for teachers to reinvigorate their classrooms and their own attitudes toward creative writing. In four complementary sections focusing on four groups of writers--creative writers in residence, K-12 students and teachers who participated in the summer institutes, and established writers such as Ron Carlson and Scott Russell Sanders--the book demonstrates the enormous variety and high quality of writing that result when people use writing to discover what they want to say. After an introduction by Robert Fox ("The Experience of Writing: A Summer Institute"), the first section presents essays by Ohio writers in the schools; "Doing Our Own Possibility: Journal of a Residency at Columbiana County Head Start Centers" (Debra Conner); "Playwriting: A Teaching Approach Using the Stories of Our Lives" (Michael McGee London); "Just across the Street: The Story of a Teacher-Based Residency" (Lynn Powell); "Translytics: Creative Writing Derived from Foreign Language Texts" (Nick Muska); "How to Do a Poetry Night Hike" (Terry Hermsen); and "Reading to a Sky of Soba" (David Hassler) .The second part presents poems, stories, and plays from 13 Ohio schools.