In the Middle: North of 45 Susan A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Female Fashion Is a Fickle Thing, Constantly Changing: Hemlines Rise and Fall, Fabrics Gain and Lose Favor, Colors and Patterns Cycle Through Popularity

HISTORY swimsuitof the female Fashion is a fickle thing, constantly changing: hemlines rise and fall, fabrics gain and lose favor, colors and patterns cycle through popularity. Each era has its own definitive style which encompasses not only the aesthetic, but is also reflective of the cultural norms, moral attitudes, and even available technologies of the time. The corsets and crinolines of Victorian times are a far cry from the miniskirts and platform shoes of the 1960s. Most don’t think of the swimsuit as a culturally significant fashion item, but it has a long and colorful history going back thousands of years with an evolution that might surprise you. And though we can’t be certain, one thing (probably) hasn’t changed at all—the agony and ecstasy of finding the perfect swimsuit. In the beginning… Public bathing was very popular in ancient Greece and Rome. Scholars believe that men and women of the upper class wore swimsuits in the bath houses. The earliest known image of women wearing swimsuits is from the early 4th century. “The Bikini Girls” mosaic decorated the floor of a Roman bath at the Villa Roma de Casale near Piazza Armer- ina, Sicily. The women are shown exercising and competing in various athletic events clad in what looks much like a modern bikini. The only exercise that didn’t require a swim- suit at the time was swimming. Romans chose to do that in the nude. modesty over fashion It wasn’t until the mid-1800s that swimming in the ocean returned as a popular leisure activity. -

Naturist Cuba: So Close, Or So Far Away

South Florida Free Beaches Florida Naturist Association Autumn 2006 Oct–Dec Vol. 6 – No. 4 www.sffb.com NATURIST CUBA: SO CLOSE, OR SO FAR AWAY... Ninety miles from Florida, and officially out-of-bounds for most U.S. citizens, Cuba gives a warm welcome to naturist tourists from Canada, Europe, and South America. story on page 4 2 The SunDial A Quarterly Journal of Florida Naturism Online version/advertiser information & rates: www.sffb.com/sundial.html Email: [email protected] Phone: 305-893-8838 Fax: 305-893-8823 Editor: Michael Kush SUN CLUB Printer: SFFB’s Naturist Social Group Thompson Press, Inc. (offset lithography) 16201 NW 54th Avenue, Miami, FL 33014 View currently planned open public events 305-625-8800 Sign up for Evite event announcements Publisher: of member-only events & parties www.sffb.com/sunclub [case sensitive] Phone inquiries: 954-961-2908 Get ready for The Naturist Society Florida Naturist Association, Inc. 2007 Naturist Gatherings & Festivals PO Box 530306, Miami Shores, FL 33153 Incorporated 1980 – Creators & mentors of Haulover Info at: www.naturistsociety.com Park’s clothing-optional naturist family beach— Dedicated to preserving and protecting free beaches The first event is the annual and naturist rights in Florida. Mid-Winter Naturist Festival Website: www.sffb.com at Sunsport Gardens Naturist Resort SFFB/FNA Officers, Directors & Beach Ambassadors: Loxahatchee (Palm Beach) Richard Mason, President & Treasurer pro temp Norma Mitchell, Vice-president President’s Day Weekend – February David Baum, Secretary [open office], Treasurer Info at: www.sunsportgarden.com SFFB/FNA Directors & Beach Ambassadors: Justin Hopkins – Paul Friderich, Jr. Join hundreds of naturists from across the USA Clyde Lott for an extended weekend of fellowship, sport, SFFB/FNA Beach Ambassadors: entertainment, and workshops on naturism, Annette Almanza – Marianna Biondi – Bruce Frendahl health, healing, spirituality, relationships Michael Kush – Norman “Doc” McClesky and a multitude of other topics. -

M&S: Swimwear

M&S: Swimwear Style for the sun since the 1930s 1920s & 1930s In 1928 we sold bathing suits and bathing caps. Customers shopping for their holidays at M&S in the 1930s would have seen our advertising leaflet for woollen swimsuits. The swimsuits were colour-fast to both sea and sun so were wearable, durable and fashionable. The first swimsuits were offered in a variety of styles to suit the wearer’s modesty: from ‘a regulation one piece... which essentially spells swimming’ to ‘a combined brassiere and shorts to give the utmost comfort and freedom’. Swimwear Marketing Leaflet, 1930s Ref: HO/11/1/5/27 1939 Swimwear available in 1939 included expanding swimsuits, and swimsuits with ripple stitch detail. In the late 1930s we sold knitting patterns for clothing, including swimsuits. Knitting Pattern, late 1930s 1950s After the Second World War, Chairman Simon Marks knew the M&S customer was demanding ‘better materials, better design, better finish…’ Scientific developments made during the war were used to fulfil customers’ needs. New fabrics such as rayon and nylon were widely used to provide people with easy-wear, easy-care garments, and were perfect for swimwear. Shape-enhancing features, such as padded busts were introduced and strapless styles became popular. For men, swimming trunks with elasticated waists were big sellers in the 1950s. Blue Cotton Swimsuit, 1950s Ref: T52/3 1962 In the 1960s beachwear became more popular with customers. The M&S stand at the 1962 Ideal Home Show sold as much swimwear in one day as an average store would sell in a week! The stand was St Michael News, Spring 1962 a joint venture between M&S and British Nylon Spinners to promote Bri-Nylon. -

Dallas Striptease 1946-1960 A

FROM MIDWAY TO MAINSTAGE: DALLAS STRIPTEASE 1946-1960 A Thesis by KELLY CLAYTON Submitted to the Graduate School of Texas A&M University-Commerce in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2019 FROM MIDWAY TO MAINSTAGE: DALLAS STRIPTEASE 1946-1960 A Thesis by KELLY CLAYTON Approved by: Advisor: Jessica Brannon-Wranosky Committee: Sharon Kowalsky Andrew Baker Head of Department: Sharon Kowalsky Dean of the College: William Kuracina Dean of the Graduate School: Matthew A. Wood iii Copyright © 2019 Kelly Clayton iv ABSTRACT FROM MIDWAY TO MAINSTAGE: DALLAS STRIPTEASE 1946-1960 Kelly Clayton, MA Texas A&M University-Commerce, 2019 Advisor: Jessica Brannon-Wranosky PhD The entertainment landscape of post-World War II Dallas, Texas included striptease in different types of venues. Travelling and local striptease acts performed at the city’s annual fair and in several nightclubs in the city. In the late 1940s, the fair featured striptease as the headlining act, and one of the city’s newspapers, the Dallas Morning News, described the dancers as the most popular attraction of the largest fair in the United States. Further, the newspaper reporting congratulated the men who ran the fair for providing Texans with these popular entertainment options. The dancers who performed at the fair also showcased their talents at area nightclubs to mixed gender audiences. Dallas welcomed striptease as an acceptable form of entertainment. However, in the early 1950s, the tone and tenor of the striptease coverage changed. The State Fair of Texas executives decried striptease as “soiled” and low-class. Dancers performed in nightclubs, but the newspaper began to report on one particular entertainer, Candy Barr, and her many tangles with law enforcement. -

Miraclesuit Size Guide

THE MIRACLE Who is Miraclesuit for? The Miraclesuit collection is designed to appeal to women of all ages and sizes— there is something for everyone and every body. When a woman wears her Miraclesuit, she feels confident and beautiful: a celebration of herself. Design and inspiration At Miraclesuit, we believe in curves. The Miraclesuit heritage of fit, form and function continues to be the basis of the collection. With an emphasis on beautiful prints and luxurious solids, Miraclesuit's updated silhouettes utilize innovative construction and design. A collection of FIT TIPS coordinating cover-ups completes a woman’s destination wardrobe. What’s the Miracle? Miraclesuit is the swimsuit that comfortably contours, shapes, slims and firms the body without constricting movement so a woman can spend more time relaxing and less time worrying about how she looks in a swimsuit. Miraclesuit begins with our unique and innovative fabric, Miratex®, which has over twice the amount of LYCRA® and three times the holding power than any other swimsuit. When a woman puts on a Miraclesuit, she appears 10 lbs. lighter in 10 seconds®—the amount of time is takes her to slip it on. FIT TIPS FINDING YOUR FIT HOW TO MEASURE GENERAL TIPS If a suit doesn’t fit right, it won’t ever look or feel right! Always begin with the right size. Choosing the right size When purchasing a Miraclesuit for the first time, many customers order a swimsuit Straps Can you fit your Back Check coverage. Bust Measure around Hips Measure around in their usual size for the most comfortable and slimming fit. -

Swimsuit Policy URJ Greene Family Camp 2016

Swimsuit Policy URJ Greene Family Camp 2016 At GFC, we believe in teaching our staff and campers the value behind creating a community that allows for freedom to self-express and self-identify. We also believe these expressions contribute to our Jewish community at camp. As a community, we represent Greene Family Camp, the URJ, the Jewish people, and ourselves as individuals. We have a critical role as exemplars of Jewish values for our campers. One such value, particularly in today's society, is tzniut, or modesty in dress. It is important to always keep this in mind when we get dressed every day at camp—for the day, for evening programs, for Shabbat, and for the pool. This year, we want to dive right in to a new way of representing ourselves. Certain types of clothing and swimwear that have been worn at camp in the past—by both staff members and campers, male and female—are becoming too revealing. Because of this, we want to bring back a sense of tzniut in our clothing and swimwear. Being more modest does not necessarily mean that we can’t still be stylish or fashion-forward. There is a way to still wear a stylish swimsuit while also being fully comfortable in the water and fully covered at all times. Here are a few guidelines for the type of swimsuits that you should pack for camp this summer: Swimsuits for Male Campers/Staff • Your swimsuit should fully cover every intimate body part. • The shortest length that trunks or board shorts should be is mid-thigh length. -

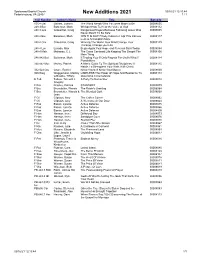

New Additions 2021 1 / 1

Spotswood Baptist Church 03/16/21 12:10:44 Federicksburg, VA 22407 New Additions 2021 1 / 1 Call Number Author's Name Title Barcode 155.4 Gai Gaines, Joanna The World Needs Who You were Made to Be 00008055 248.3 Bat Batterson, Mark Whisper:How To Hear the Voice of God 00008112 248.3 Gro Groeschel, Craig Dangerous Prayers:Because Following Jesus Was 00008095 Never Meant To Be Safe 248.4 Bat Batterson, Mark WIN THE DAY:7 Daily Habits to Help YOu bStress 00008117 Less & Accomplish More 248.4 Gro Groeschel, Craig Winning The WarIn Your Mind:Change Your 00008129 Thinking, Change your Life 248.4 Luc Lucado, Max Begin Again:Your Hope and Renewal Start Today 00008054 248.4 Mah Mahaney, C.J. The Cross Centered Life:Keeping The Gospel The 00008106 Main Thing 248.842 Bat Batterson, Mark If:Trading Your If Only Regrets For God's What If 00008114 Possibilities 248.842 Mor Morley, Patrick A Man's Guide To The Spiritual Disciplines:12 00008115 Habits To Strengthen Your Walk With Christ 332.024 Cru Cruze, Rachel Know Yourself Know Your Money 00008060 920 Weg Weggemann, Mallory LIMITLESS:The Power Of Hope And Resilience To 00008118 w/Brooks, Tiffany Overcome Circumstance E Teb Tebow, Tim w/A.J. A Party To Remember 00008018 Gregory F Bra Bradley, Patricia STANDOFF 00008079 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda The Robin's Greeting 00008084 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda & The Blended Quilt 00008068 Jean F Cli Clipston, Amy The Coffee Corner 00008062 F Cli Clipston, Amy A Welcome At Our Door 00008064 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active Defense 00008015 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active -

Dsr-Newsletter-03-08-2021-Sfw.Pdf

March 8, 2021 Volume 21, Issue 8 Weekly Newsletter The new owners were received very well by the residents, members and guests that attended the meet and greet Saturday afternoon. Many great topics were briefly discussed transferring an amazingly certain future for the resort and anyone visiting. The owners are now chipping away at their ar- rangement of assault and with the incredible input they received during the Inside this issue occasion can now focus on the process pushing ahead. Be Yourself.................................. 3 They discussed a portion of the numerous amenities they intend to bring to Is there a human “need” ............ 3 the resort for everybody's delight. They spoke of some of the new activities Getting a Naturist Volunteer Job 4 they will be adding in the future. This will not be an overnight revitalization of Nude Beaches ............................ 4 the resort and we ask that you bear with us throughout the process. Obsessed with streaking ............. 5 Clean up of the resort has already begun. This is the initial step and will ac- Nudist Comedy DISROBED ......... 6 count for future changes. We are asking all site holders to begin the process poses at tourist spots ................. 6 of springtime site cleanup as well. Naturist Accommodations .......... 6 Please, stay tuned to our newsletter as this is the place where you will locate Chelsea Handler .......................... 8 the most data about the renewal of the resort. We are looking forward to the coming days, months, and years, as the new ideas are implemented. AANR Newsletter Attention Residents If you have not yet returned your questionnaire, please do so. -

The Essay As Art Form

The Essay as Art Form Emily LaBarge A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Royal College of Art for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 Royal College of Art 2 Copyright This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Royal College of Art. This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research for private study, on the understanding that it is copyright material, and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. 3 Abstract Beginning with Montaigne’s essayistic dictum Que sais je? — ‘What do I know?’ — this PhD thesis examines the literary history, formal qualities, and theoretical underpinnings of the personal essay to both investigate and to practice its relevance as an approach to writing about art. The thesis proposes the essay as intrinsically linked to research, critical writing, and art making; it is a literary method that embodies the real experience of attempting to answer a question. The essay is a processual and reflexive mode of enquiry: a form that conveys not just the essayist’s thought, but the sense and texture of its movement as it attempts to understand its object. It is often invoked, across disciplines, in reference to the possibility of a more liberal sense of creative practice — one that conceptually and stylistically privileges collage, fragmentation, hybridity, chance, open-endedness, and the meander. Within this question of the essay as form, the thesis contains two distinct and parallel strands of analysis — subject matter and essay writing as research. -

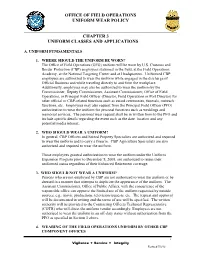

Office of Field Operations Uniform Wear Policy

OFFICE OF FIELD OPERATIONS UNIFORM WEAR POLICY CHAPTER 3 UNIFORM CLASSES AND APPLICATIONS A. UNIFORM FUNDAMENTALS 1. WHERE SHOULD THE UNIFORM BE WORN? The Office of Field Operations (OFO) uniform will be worn by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) employees stationed in the field, at the Field Operations Academy, at the National Targeting Center and at Headquarters. Uniformed CBP employees are authorized to wear the uniform while engaged in the discharge of Official Business and while traveling directly to and from the workplace. Additionally, employees may also be authorized to wear the uniform by the Commissioner, Deputy Commissioner, Assistant Commissioner, Office of Field Operations, or Principal Field Officer (Director, Field Operations or Port Director) for other official or CBP-related functions such as award ceremonies, funerals, outreach functions, etc. Employees may also request from the Principal Field Officer (PFO) authorization to wear the uniform for personal functions such as weddings and memorial services. The personal wear request shall be in written form to the PFO and include specific details regarding the event such as the date, location and any potential media interest. 2. WHO SHOULD WEAR A UNIFORM? In general, CBP Officers and Seized Property Specialists are authorized and required to wear the uniform and to carry a firearm. CBP Agriculture Specialists are also authorized and required to wear the uniform. Those employees granted authorization to wear the uniform under the Uniform Expansion Program prior to December 8, 2008, are authorized to retain their uniformed status regardless of their Enhanced Retirement coverage. 3. WHO SHOULD NOT WEAR A UNIFORM? Persons who are not employed by CBP are not authorized to wear the uniform or be dressed in a manner that attempts to duplicate the appearance of the uniform. -

In the Supreme Court of Iowa

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF IOWA No. 10–0898 Filed July 27, 2012 MALL REAL ESTATE, L.L.C., an Iowa Limited Liability Company, Appellant, vs. CITY OF HAMBURG, an Iowa Municipal Corporation, Appellee. Appeal from the Iowa District Court for Fremont County, Greg W. Steensland, Judge. An establishment appeals an order denying its request for an injunction enjoining a city from enforcing an ordinance regulating nude dancing. REVERSED AND REMANDED WITH INSTRUCTIONS. W. Andrew McCullough, Midvale, Utah, and Brian B. Vakulskas and Daniel P. Vakulskas of Vakulskas Law Firm, Sioux City, for appellant. Raymond R. Aranza of Scheldrup Blades Schrock Smith Aranza, P.C., Cedar Rapids, for appellee. 2 WIGGINS, Justice. The operator of an establishment offering nude and seminude dance performances sought an injunction restraining a city from enforcing its ordinance regulating nude and seminude dancing. The district court found that state law did not preempt the ordinance and that the ordinance was constitutional. On appeal, we find that state law preempts enforcement of the ordinance and that it is unenforceable against the establishment. Accordingly, we reverse the judgment of the district court and remand the case with instructions to the court to enter an order enjoining the city from enforcing its ordinance against the establishment. I. Background Facts and Proceedings. On December 8, 2008, the Hamburg city council passed chapter 48 of its city code. The ordinance, known as the “Sexually Oriented Business Ordinance,” contains provisions relating to licensing and zoning and imposes a range of regulations upon sexually oriented businesses. The stated purpose of the ordinance is to “regulate sexually oriented businesses in order to promote the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of the citizens of the City, and to establish reasonable and uniform regulations to prevent the deleterious secondary effects of sexually oriented businesses.” Hamburg, Iowa, Code § 48.010.01 (Dec. -

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Mary Henry Pansynclastic Riddle 1966, 48 x 61.5 Courtesy of the Artist and Bryan Ohno Gallery Cover photo: Hilda Morris in her studio 1964 Photo: Hiro Moriyasu Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism Organized by The Art Gym, Marylhurst University 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington with support from the Regional Arts and Culture Council, the Lamb Foundation, members and friends. The Art Gym, Marylhurst University, Marylhurst, Oregon Kathleen Gemberling Adkison September 26 – November 20, 2004 Doris Chase Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner, Washington January 15 – April 3, 2005 Sally Haley Mary Henry Maude Kerns LaVerne Krause Hilda Morris Eunice Parsons Viola Patterson Ruth Penington Amanda Snyder Margaret Tomkins Eunice Parsons Mourning Flower 1969, collage, 26 x 13.5 Collection of the Artist Photo: Robert DiFranco Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Copyright 2004 Marylhurst University Post Offi ce Box 261 17600 Pacifi c Highway Marylhurst, Oregon 97036 503.636.8141 www.marylhurst.edu Artworks copyrighted to the artists. Essays copyrighted to writers Lois Allan and Matthew Kangas. 2 All rights reserved. ISBN 0-914435-44-2 Design: Fancypants Design Preface Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve presented work created prior to 1970. Most of our Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington exhibitions either present art created specifi cally grew out of a conversation with author and for The Art Gym, or are mid-career or retrospective critic Lois Allan. As women, we share a strong surveys of artists in the thick of their careers.