Anthems, Sonnets, and Chants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

COMING MARCH 30! WOMEN's HISTORY TRIP to Cambridge

COMING MARCH 30! WOMEN’S HISTORY TRIP to Cambridge, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore, to see the Harriet Tubman Museum and the Annie Oakley House. Call 301-779-2161 by Tuesday, March 12 to reserve a seat. CALL EARLY! Limited number of seats on bus - first ones to call will get available seats. * * * * * * * MARCH IS WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH – AND HERE ARE SOME WOMEN FROM MARYLAND’s AND COTTAGE CITY’s PAST! By Commissioner Ann Marshall Young There are many amazing women in Maryland and Cottage City’s history. These are just a few, to give you an idea of some of the “greats” we can claim: Jazz singer Billie Holiday (1915 – 1959) was born Eleanora Fagan, but took her father’s surname, Holiday, and “Billie” from a silent film star. As a child she lived in poverty in East Baltimore, and later gave her first performance at Fell’s Point. In 1933 she was “discovered” in a Harlem nightclub, and soon became wildly popular, with a beautiful voice and her own, truly unique style. Her well-known song, “Strange Fruit,” described the horrors of lynchings in Jim Crow America. Through her singing, she raised consciousness about racism as well as about the beauties of African-American culture. Marine biologist and conservationist Rachel Carson (1907-1964) wrote the book Silent Spring, which, with her other writings, is credited with advancing the global environmental movement. Although opposed by chemical companies, her work led to a nationwide ban on DDT and other pesticides, and inspired a grassroots environmental movement that led to the creation of the U.S. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

Pocketciv a Solitaire Game of Building Civilizations

PocketCiv A solitaire game of building civilizations. (version:07.11.06) OBJECT: Starting with a few tribes, lead your civilization through the ages to become...civilized. COMPONENTS: What you will definitely need: • The deck of Event cards If you are playing, basic, no frills, true PocketCiv style, you will additionally need: • A pencil • A pad of paper • This set of rules • A printout of the Advances and Wonders If you want to play a bunch of pre-built Scenarios, you will need: • The Scenario book Finally, if you want a full “board game” experience, you will need to download, printout and mount: • The files that contains the graphics for the Resource Tiles, and Land Masses • The deck of Advances and Wonders • Poker chips (for keeping track of Gold) • Glass Beads or wood cubes (for use as Tribes) A FEW WORDS OF NOTE: It should be noted here that since this is a solitaire game, the system is fairly open-ended to interpretation, and how you want to play it. For example, while in the following "Build Your World" section, it talks about creating a single Frontier area; there's nothing that prevents you from breaking up the Frontier into two areas, which would give you two Sea areas, as if your Empire is in the middle of a peninsula. It's your world, feel free to play with it as much as you like. Looking at the scenario maps will give you an idea how varied you can make your world. However, your first play should conform fairly close to these given rules, as the rules and events on the cards pertain to these rules. -

Radical Pacifism, Civil Rights, and the Journey of Reconciliation

09-Mollin 12/2/03 3:26 PM Page 113 The Limits of Egalitarianism: Radical Pacifism, Civil Rights, and the Journey of Reconciliation Marian Mollin In April 1947, a group of young men posed for a photograph outside of civil rights attorney Spottswood Robinson’s office in Richmond, Virginia. Dressed in suits and ties, their arms held overcoats and overnight bags while their faces carried an air of eager anticipation. They seemed, from the camera’s perspective, ready to embark on an exciting adventure. Certainly, in a nation still divided by race, this visibly interracial group of black and white men would have caused people to stop and take notice. But it was the less visible motivations behind this trip that most notably set these men apart. All of the group’s key organizers and most of its members came from the emerging radical pacifist movement. Opposed to violence in all forms, many had spent much of World War II behind prison walls as conscientious objectors and resisters to war. Committed to social justice, they saw the struggle for peace and the fight for racial equality as inextricably linked. Ardent egalitarians, they tried to live according to what they called the brotherhood principle of equality and mutual respect. As pacifists and as militant activists, they believed that nonviolent action offered the best hope for achieving fundamental social change. Now, in the wake of the Second World War, these men were prepared to embark on a new political jour- ney and to become, as they inscribed in the scrapbook that chronicled their traveling adventures, “courageous” makers of history.1 Radical History Review Issue 88 (winter 2004): 113–38 Copyright 2004 by MARHO: The Radical Historians’ Organization, Inc. -

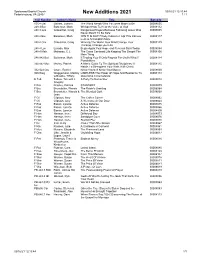

New Additions 2021 1 / 1

Spotswood Baptist Church 03/16/21 12:10:44 Federicksburg, VA 22407 New Additions 2021 1 / 1 Call Number Author's Name Title Barcode 155.4 Gai Gaines, Joanna The World Needs Who You were Made to Be 00008055 248.3 Bat Batterson, Mark Whisper:How To Hear the Voice of God 00008112 248.3 Gro Groeschel, Craig Dangerous Prayers:Because Following Jesus Was 00008095 Never Meant To Be Safe 248.4 Bat Batterson, Mark WIN THE DAY:7 Daily Habits to Help YOu bStress 00008117 Less & Accomplish More 248.4 Gro Groeschel, Craig Winning The WarIn Your Mind:Change Your 00008129 Thinking, Change your Life 248.4 Luc Lucado, Max Begin Again:Your Hope and Renewal Start Today 00008054 248.4 Mah Mahaney, C.J. The Cross Centered Life:Keeping The Gospel The 00008106 Main Thing 248.842 Bat Batterson, Mark If:Trading Your If Only Regrets For God's What If 00008114 Possibilities 248.842 Mor Morley, Patrick A Man's Guide To The Spiritual Disciplines:12 00008115 Habits To Strengthen Your Walk With Christ 332.024 Cru Cruze, Rachel Know Yourself Know Your Money 00008060 920 Weg Weggemann, Mallory LIMITLESS:The Power Of Hope And Resilience To 00008118 w/Brooks, Tiffany Overcome Circumstance E Teb Tebow, Tim w/A.J. A Party To Remember 00008018 Gregory F Bra Bradley, Patricia STANDOFF 00008079 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda The Robin's Greeting 00008084 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda & The Blended Quilt 00008068 Jean F Cli Clipston, Amy The Coffee Corner 00008062 F Cli Clipston, Amy A Welcome At Our Door 00008064 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active Defense 00008015 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active -

A Guide for Teaching the Contributions of the Negro Author to American Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 043 635 TE 002 075 AUTHOR Simon, Eugene r. TITLE A Guide for Teaching the Contributions of the Negro Author to American Literature. INSTITUTION San Diego City Schools, Calif. PUB DATE 68 NOTE uln. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 BC-$2.1 DESCRIPTORS *African American Studies, *American Literature, Authors, Autobiographies, Piographies, *Curriculum Guides, Drama, Essays, Grade 11, Music, Negro Culture, Negro History, *Negro Literature, Novels, Poetry, Short Stories ABSTRACT This curriculum guide for grade 11 was written to provide direction for teachers in helping students understand how Negro literature reflects its historical background, in integrating Black literature into the English curriculum, in teaching students literary structure, and in comparing and contrasting Negro themes with othr themes in American literature. Brief outlines are provided for four literary periods; (1) the cry for freedom (1619-186c), (2) the period of controversy and search for identity (18(5-1015), (1) the Negro Renaissance (191-1940), and (4) the struggle for equality (101-1968). '*he section covering the Negro Renaissance provides a discussiol of the contributions made during that Period in the fields of the short sto:y, the essay, the novel, poetry, drama, biography, and autobiography.A selected bibliography of Negro literalAre includes works in all these genres as well as works on American Negro music. (D!)) U.S. DIPAIIMINI Of KEITH, MOTION t WItfANI Ulla Of EDUCATION L11 rIN iMIS DOCUMENT HAS SUN IMPRODIXID HAIR IS WINED FROM EIIE PINSON Of ONINI/AliON 011411111110 ElPOINTS Of VIEW Of OPINIONS tes. MUD DO NOT NICISSAINY OMEN! Offg lit OHM Of EDIKIIION POSITION 01 PEW. -

The Essay As Art Form

The Essay as Art Form Emily LaBarge A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Royal College of Art for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 Royal College of Art 2 Copyright This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Royal College of Art. This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research for private study, on the understanding that it is copyright material, and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. 3 Abstract Beginning with Montaigne’s essayistic dictum Que sais je? — ‘What do I know?’ — this PhD thesis examines the literary history, formal qualities, and theoretical underpinnings of the personal essay to both investigate and to practice its relevance as an approach to writing about art. The thesis proposes the essay as intrinsically linked to research, critical writing, and art making; it is a literary method that embodies the real experience of attempting to answer a question. The essay is a processual and reflexive mode of enquiry: a form that conveys not just the essayist’s thought, but the sense and texture of its movement as it attempts to understand its object. It is often invoked, across disciplines, in reference to the possibility of a more liberal sense of creative practice — one that conceptually and stylistically privileges collage, fragmentation, hybridity, chance, open-endedness, and the meander. Within this question of the essay as form, the thesis contains two distinct and parallel strands of analysis — subject matter and essay writing as research. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

UNIT COUNTER POOL Both

11/23/2020 UNIT COUNTER POOL Home New Member Application Members Guide About Us Open Match Requests Unit Counter Pool AHIKS UNIT COUNTER POOL To request a lost counter, rulebook or accessory, email the UCP custodian, Brian Laskey at [email protected] ! Please Note: In order to use the Unit Counter Pool you must be a current member of AHIKS. If you are not a member but would like to find out how to join please go to the New Member Application page or click here!! AVALON HILL-VICTORY GAMES Across Five Aprils General 25-2 Counter Insert Advanced Civilization Bulge ‘81 Afrika Korps Empires in Arms Air Assault on Crete 1776 Anzio Tac Air ASL (Beyond Valor, Red Barricades, Yanks) B-17 General 26-3 Counter Insert Bismarck Flight Leader Blitzkreig Firepower Bitter Woods (1st ed. No Utility), 2nd ed Merchant of Venus Breakout Normandy Bulge ‘65 General 28-5 Counter Insert Bulge ’81 Midway/Guadalcanal Expansion Bulge ’91 Bull Run Caesar’s Legions Merchant of Venus Chancellorsville Panzer Armee Afrika Civil War Panzer Blitz Desert Storm (Gulf Strike: Desert Shield) Panzerkrieg D-Day Panzer Leader Devil’s Den Russian Campaign 1809 Siege of Jerusalem (Roman Only) Empires in Arms 1776 Firepower Stalingrad (Original) Flashpoint Golan Stalingrad (AHgeneral.org version) Flat Top (No Markers) Storm over Arnhem Fortress Europa Squad Leader France 1940 Submarine Gettysburg ‘77 Tactics II GI Anvil (German & SS Infantry; Small Third Reich file:///C:/Users/Owner/Desktop/UNIT COUNTER POOL.html 1/5 11/23/2020 UNIT COUNTER POOL Arms) Guadalcanal Tobruk Turning -

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Mary Henry Pansynclastic Riddle 1966, 48 x 61.5 Courtesy of the Artist and Bryan Ohno Gallery Cover photo: Hilda Morris in her studio 1964 Photo: Hiro Moriyasu Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism Organized by The Art Gym, Marylhurst University 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington with support from the Regional Arts and Culture Council, the Lamb Foundation, members and friends. The Art Gym, Marylhurst University, Marylhurst, Oregon Kathleen Gemberling Adkison September 26 – November 20, 2004 Doris Chase Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner, Washington January 15 – April 3, 2005 Sally Haley Mary Henry Maude Kerns LaVerne Krause Hilda Morris Eunice Parsons Viola Patterson Ruth Penington Amanda Snyder Margaret Tomkins Eunice Parsons Mourning Flower 1969, collage, 26 x 13.5 Collection of the Artist Photo: Robert DiFranco Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Copyright 2004 Marylhurst University Post Offi ce Box 261 17600 Pacifi c Highway Marylhurst, Oregon 97036 503.636.8141 www.marylhurst.edu Artworks copyrighted to the artists. Essays copyrighted to writers Lois Allan and Matthew Kangas. 2 All rights reserved. ISBN 0-914435-44-2 Design: Fancypants Design Preface Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve presented work created prior to 1970. Most of our Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington exhibitions either present art created specifi cally grew out of a conversation with author and for The Art Gym, or are mid-career or retrospective critic Lois Allan. As women, we share a strong surveys of artists in the thick of their careers.