Composition Studies 39.2 Fall 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applying Theories of Digital Rhetoric, Procedural Rhetoric, and Electracy To

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2018-01-01 Rethinking Multimodality In First-Year Composition: Applying Theories Of Digital Rhetoric, Procedural Rhetoric, And Electracy To Multimodal Assignments Jennifer Falcon University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Falcon, Jennifer, "Rethinking Multimodality In First-Year Composition: Applying Theories Of Digital Rhetoric, Procedural Rhetoric, And Electracy To Multimodal Assignments" (2018). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1426. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1426 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RETHINKING MULTIMODALITY IN FIRST-YEAR COMPOSITION: APPLYING THEORIES OF DIGITAL RHETORIC, PROCEDURAL RHETORIC, AND ELECTRACY TO MULTIMODAL ASSIGNMENTS JENNIFER ANDREA FALCON Doctoral Program in Rhetoric and Composition APPROVED: Beth Brunk-Chavez, Ph.D., Chair Laura Gonzales, Ph.D. William Robertson, Ph.D. Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Jennifer Andrea Falcon 2018 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my grandfather, José Franco Sandoval. Grandpa, your devotion to hard work and education will always guide me. RETHINKING MULTIMODALITY IN FIRST-YEAR -

Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles and Politics

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/161 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles and Politics Edited by Brett D. Hirsch http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2012 Brett D. Hirsch et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). Some rights are reserved. The articles of this book are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported Licence. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Details of allowances and restrictions are available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ As with all Open Book Publishers titles, digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/161 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-26-8 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-25-1 ISBN Digital (pdf): 978-1-909254-27-5 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-28-2 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-29-9 Typesetting by www.bookgenie.in Cover image: © Daniel Rohr, ‘Brain and Microchip’, product designs first exhibited as prototypes in January 2009. Image used with kind permission of the designer. For more information about Daniel and his work, see http://www.danielrohr.com/ All paper used by Open Book Publishers is SFI (Sustainable Forestry Initiative), and PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes) Certified. -

Collin College in May 20162—

Appellate Case: 18-6102 Document: 010110085921 Date Filed: 11/19/2018 Page: 1 Case No. 18-6102/ 18-6165 In the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit ___________________ DR. RACHEL TUDOR, Plaintiff-Appellant/Cross-Appellee v. SOUTHEASTERN OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY AND REGIONAL UNIVERSITY SYSTEM OF OKLAHOMA, Defendants-Appellees/Cross-Appellants ___________________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma, Case No. 5:15-cv-324-C, Hon. Robin Cauthron ___________________ PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT/CROSS-APPELLEE DR. RACHEL TUDOR’S APPENDIX VOLUME 3 OF 9 ___________________ EZRA ISHMAEL YOUNG BRITTANY M. NOVOTNY LAW OFFICE OF EZRA YOUNG NATIONAL LITIGATION LAW GROUP 30 Devoe Street, #1A PLLC Brooklyn, NY 11211 2401 NW 23rd St., Ste. 42 (949) 291-3185 Oklahoma City, OK 73107 [email protected] (405) 896-7805 [email protected] MARIE EISELA GALINDO LAW OFFICE OF MARIE E. GALINDO Wells Fargo Bldg. 1500 Broadway, Ste. 1120 Lubbock, TX 79401 (806) 549-4507 [email protected] Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant/Cross-Appellee Case No. 18-6102/ 18-6165 Appellate Case: 18-6102 Document: 010110085921 Date Filed: 11/19/2018 Page: 2 VOLUME 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 15-CV-324-C – Relevant Docket Entries Appendix Filer Date of Doc Title of Pleading Pg. # Filing # 001-010 Plaintiff 12/29/2017 271 Reply to Defendants’ Opposition to Reinstatement 011-026 Plaintiff 12/29/2017 271- Reply to Response to 1 Motion for Order for Reinstatement Exhibit 1 Tudor Declaration 027-116 Plaintiff 12/29/2017 271- Reply -

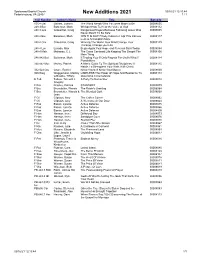

New Additions 2021 1 / 1

Spotswood Baptist Church 03/16/21 12:10:44 Federicksburg, VA 22407 New Additions 2021 1 / 1 Call Number Author's Name Title Barcode 155.4 Gai Gaines, Joanna The World Needs Who You were Made to Be 00008055 248.3 Bat Batterson, Mark Whisper:How To Hear the Voice of God 00008112 248.3 Gro Groeschel, Craig Dangerous Prayers:Because Following Jesus Was 00008095 Never Meant To Be Safe 248.4 Bat Batterson, Mark WIN THE DAY:7 Daily Habits to Help YOu bStress 00008117 Less & Accomplish More 248.4 Gro Groeschel, Craig Winning The WarIn Your Mind:Change Your 00008129 Thinking, Change your Life 248.4 Luc Lucado, Max Begin Again:Your Hope and Renewal Start Today 00008054 248.4 Mah Mahaney, C.J. The Cross Centered Life:Keeping The Gospel The 00008106 Main Thing 248.842 Bat Batterson, Mark If:Trading Your If Only Regrets For God's What If 00008114 Possibilities 248.842 Mor Morley, Patrick A Man's Guide To The Spiritual Disciplines:12 00008115 Habits To Strengthen Your Walk With Christ 332.024 Cru Cruze, Rachel Know Yourself Know Your Money 00008060 920 Weg Weggemann, Mallory LIMITLESS:The Power Of Hope And Resilience To 00008118 w/Brooks, Tiffany Overcome Circumstance E Teb Tebow, Tim w/A.J. A Party To Remember 00008018 Gregory F Bra Bradley, Patricia STANDOFF 00008079 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda The Robin's Greeting 00008084 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda & The Blended Quilt 00008068 Jean F Cli Clipston, Amy The Coffee Corner 00008062 F Cli Clipston, Amy A Welcome At Our Door 00008064 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active Defense 00008015 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active -

Composition Studies 42.1 (2014) from the Editor Hat’S the Best Part of Your Job?” a Student in Advanced Composition “Wasked Me This Question Last Week

Volume 42, Number 1 Spring 2014 composition STUDIES composition studies volume 42 number 1 Composition Studies C/O Parlor Press 3015 Brackenberry Drive Anderson, SC 29621 New Releases First-Year Composition: From Theory to Practice Edited by Deborah Coxwell-Teague & Ronald F. Lunsford. 420 pages. Twelve of the leading theorists in composition stud- ies answer, in their own voices, the key question about what they hope to accomplish in a first-year composition course. Each chapter, and the accompanying syllabi, pro- vides rich insights into the classroom practices of these theorists. A Rhetoric for Writing Program Administrators Edited by Rita Malenczyk. 471 pages. Thirty-two contributors delineate the major issues and questions in the field of writing program administration and provide readers new to the field with theoretical lenses through which to view major issues and questions. Recently Released . Writing Program Administration and the Community College Heather Ostman. The WPA Outcomes Statement—A Decade Later Edited by Nicholas N. Behm, Gregory R. Glau, Deborah H. Holdstein, Duane Roen, & Edward M. White. Writing Program Administration at Small Liberal Arts Colleges Jill M. Gladstein and Dara Rossman Regaignon. GenAdmin: Theorizing WPA Identities in the Twenty-First Century Colin Charlton, Jonikka Charlton, Tarez Samra Graban, Kathleen J. Ryan, & Amy Ferdinandt Stolley and with the WAC Clearinghouse . Writing Programs Worldwide: Profiles of Academic Writing in Many Places Edited by Chris Thaiss, Gerd Bräuer, Paula Carlino, Lisa Ganobcsik-Williams, & Aparna Sinha International Advances in Writing Research: Cultures, Places, Measures Edited by Charles Bazerman, Chris Dean, Jessica Early, Karen Lunsford, Suzie Null, Paul Rogers, & Amanda Stansell www.parlorpress.com 2013–2014 Reviewers A journal is only as good as its reviewers. -

The Essay As Art Form

The Essay as Art Form Emily LaBarge A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Royal College of Art for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 Royal College of Art 2 Copyright This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Royal College of Art. This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research for private study, on the understanding that it is copyright material, and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. 3 Abstract Beginning with Montaigne’s essayistic dictum Que sais je? — ‘What do I know?’ — this PhD thesis examines the literary history, formal qualities, and theoretical underpinnings of the personal essay to both investigate and to practice its relevance as an approach to writing about art. The thesis proposes the essay as intrinsically linked to research, critical writing, and art making; it is a literary method that embodies the real experience of attempting to answer a question. The essay is a processual and reflexive mode of enquiry: a form that conveys not just the essayist’s thought, but the sense and texture of its movement as it attempts to understand its object. It is often invoked, across disciplines, in reference to the possibility of a more liberal sense of creative practice — one that conceptually and stylistically privileges collage, fragmentation, hybridity, chance, open-endedness, and the meander. Within this question of the essay as form, the thesis contains two distinct and parallel strands of analysis — subject matter and essay writing as research. -

ENC 1136: Multimodal Writing & Digital Literacy ENC1136

ENC 1136: Multimodal Writing & Digital Literacy ENC1136 (Section 9122, Class 23684, SP20) Brandon Murakami MWF:3 (9:35-10:25a) [email protected] Room: M: WEIL 408D / WF: WEIL 408E OH: TBA COURSE DESCRIPTION Multimodal Composition teaches digital literacy and digital creativity. This course teaches students to compose and circulate multimodal documents in order to convey creative, well- researched, carefully crafted, and attentively written information through digital platforms and multimodal documents. This course promotes digital writing and research as central to academic, civic, and personal expression. COURSE OBJECTIVES Multimodal writing objectives are designed to teach students how to compose, revise, and circulate information in digital forms. The course emphasizes: • Applying composing processes in digital forms • Demonstrating invention/creativity approaches when working with digital resources and tools • Choosing which digital tools best serve contextual needs • Creating documents in six different forms that contribute to multimodal production (see below) • Using problem-solving methods to navigate digital tools • Appraising methods for self-guided learning about emerging digital tools (i.e. learning how to learn) REQUIRED MATERIALS Note: Many of the “readings” assigned in this class will be online tutorials for using the digital tools needed to compose, produce, and circulate the assigned documents. Because the course focuses on hands-on, active production, the focus of readings often will be tutorials and student work for critique. All texts will be provided on our course website on Canvas. GENERAL EDUCATION OBJECTIVES: COMPOSITION (C) Composition courses provide instruction in the methods and conventions of standard written English (i.e. grammar, punctuation, usage) and the techniques that produce effective texts. -

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Mary Henry Pansynclastic Riddle 1966, 48 x 61.5 Courtesy of the Artist and Bryan Ohno Gallery Cover photo: Hilda Morris in her studio 1964 Photo: Hiro Moriyasu Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism Organized by The Art Gym, Marylhurst University 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington with support from the Regional Arts and Culture Council, the Lamb Foundation, members and friends. The Art Gym, Marylhurst University, Marylhurst, Oregon Kathleen Gemberling Adkison September 26 – November 20, 2004 Doris Chase Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner, Washington January 15 – April 3, 2005 Sally Haley Mary Henry Maude Kerns LaVerne Krause Hilda Morris Eunice Parsons Viola Patterson Ruth Penington Amanda Snyder Margaret Tomkins Eunice Parsons Mourning Flower 1969, collage, 26 x 13.5 Collection of the Artist Photo: Robert DiFranco Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Copyright 2004 Marylhurst University Post Offi ce Box 261 17600 Pacifi c Highway Marylhurst, Oregon 97036 503.636.8141 www.marylhurst.edu Artworks copyrighted to the artists. Essays copyrighted to writers Lois Allan and Matthew Kangas. 2 All rights reserved. ISBN 0-914435-44-2 Design: Fancypants Design Preface Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve presented work created prior to 1970. Most of our Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington exhibitions either present art created specifi cally grew out of a conversation with author and for The Art Gym, or are mid-career or retrospective critic Lois Allan. As women, we share a strong surveys of artists in the thick of their careers. -

ULMER - Introduction: Electracy 1 to Comment on SPECIFIC PARAGRAPHS, Click on the Speech Bubble Next to That Paragraph

ULMER - Introduction: Electracy 1 To comment on SPECIFIC PARAGRAPHS, click on the speech bubble next to that paragraph. There is an analogy for what we are doing when we collaboratively explore the possibilities of new media. We are to the Internet what students of Plato and Aristotle were to the Academy and Lyceum. When the Greeks invented alphabetic writing they were engaged in a civilizational shift from one apparatus to another (from orality to literacy). They invented not only alphabetic writing but also a new institution (School) within which the practices of writing were devised. Here is the salient point: all the operators of “science” as a worldview had to be invented, by distinguishing from religion a new possibility of reason. Electracy similarly is being invented, not to replace religion and science (orality and literacy), but to supplement them with a third dimension of thought, practice, and identity. “Electracy” is to digital media what literacy is to alphabetic writing: an apparatus, or social machine, partly technological, partly institutional. We take for granted now the skill set that orients literate people to the collective mnemonics that confront anyone entering a library or classroom today. Grammatology (the history and theory of writing) shows that the invention of literacy included also a new experience of thought that led to inventions of identity as well: individual selfhood and the democratic state. Thus there are three interrelated invention streams forming a matrix of possibilities for electracy, only one of which is technological. There is no technological determinism, other than the fundamental law of change: that everything is mutating together into something other, different, with major losses and gains. -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

View Bad Ideas About Writing

BAD IDEAS ABOUT WRITING Edited by Cheryl E. Ball & Drew M. Loewe BAD IDEAS ABOUT WRITING OPEN ACCESS TEXTBOOKS Open Access Textbooks is a project created through West Virginia University with the goal of produc- ing cost-effective and high quality products that engage authors, faculty, and students. This project is supported by the Digital Publishing Institute and West Virginia University Libraries. For more free books or to inquire about publishing your own open-access book, visit our Open Access Textbooks website at http://textbooks.lib.wvu.edu. BAD IDEAS ABOUT WRITING Edited by Cheryl E. Ball and Drew M. Loewe West Virginia University Libraries Digital Publishing Institute Morgantown, WV The Digital Publishing Institute believes in making work as openly accessible as possible. Therefore, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. This license means you can re-use portions or all of this book in any way, as long as you cite the original in your re-use. You do not need to ask for permission to do so, although it is always kind to let the authors know of your re-use. To view a copy of this CC license, visit http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This book was set in Helvetica Neue and Iowan Old Style and was first published in 2017 in the United States of America by WVU Libraries. The original cover image, “No Pressure Then,” is in the public domain, thanks to Pete, a Flickr Pro user. -

Eightvolumesofle03maraiala Bw.Pdf

??ps '\%^ 1 1 , I '• ' ;" * li& J*^ '; . i•'^ fe«&i&~ /^^^^ •' ^ a 1 .\^ W^\ « Drnia 9 ""-'^•--38 al iM -- J J i^- li THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES « ' t . THE Third Volume LETTERS Wri by a Who lived Five and Forty Years, PARIS:Undifcovered, at Giving an Impartial Account to the Divan at Conjlantinofle^ of the moft remarkable Tranfadions of Europe ; and difcovering feveral Intrigues and Secrets of the ChriHinn Courts (efpecially of that of France^ continued from the Year 1645, to the Year 1682. Written Orisrinally in Arabicic, Trmjlatcd into Ita- lian, and from thence into Englifli, by theTrmfla- tor $f thi Firft VOLUME. C(;c €igl;tl) Cmtton. LONDON: Printed for J. Rhodes^ D. B'ovn, R. S^rc, B. and S. Totke, G. Strahan, W. Me'rs, S. Ballard, and F. Clay, 1723. V ^HG r U- 1 T O T H E READER. ^lJ R Arabian^ having met with fo kind Encertainmcnc j in this Nation fince he put cm the Englijh-DrcCSy is refolvei- CO continue his Garb, and vilit you as often as Convenience will, permit. He brings along with him many foreign Commodities, to gratify the various Ex- pedations of People. His Cargo confift- ing of Jewels and other Rarities, which are the genuine Product of theE*/; and fome kinds of Merchandife, which he has purchafed here in the fi'efi, during his Re fide nee at Paris. It will be pity to affront this honeil Stranger, by railing Scandals on him, as if he were a Counterfeit, and 1 know not what.