Philosophy Studies in Jesuit Formation Universities Before and After the Second Vatican Council Stephen Rowntree, S.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography on the History of the Jesuits : Publications in English

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/bibliographyonhi281begh . H nV3F mm Ǥffi fitwffii 1 unBK i$3SOul nt^ni^1 ^H* an I A'. I ' K&lfi HP HHBHHH b^SHs - HHHH hHFJISi i *^' i MPiUHraHHHN_ ^ 4H * ir Til inrlWfif O'NEILL UBRAHJ BOSTON COLLEGE Bibliography on the History of the \ Jesuits Publications in English, 1900-1993 Paul Begheyn, S.J. CD TtJ 28/1 JANUARY 1996 ft THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican IPs recom- mendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar wel- comes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclu- sively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR George M. Anderson, S.J., is associate editor of America, in New York, and writes regularly on social issues and the faith (1993). Peter D. Byrne, S.J., is rector and president of St. -

Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 4-2018 Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit Charism and Students' Moral Judgement Scott weS nson University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons Recommended Citation Swenson, Scott, "Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit Charism and Students' Moral Judgement" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 453. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/453 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STUDENTS’ PERCEPTIONS OF THE JESUIT CHARISM AND STUDENTS’ MORAL JUDGEMENT A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Department of Leadership Studies Catholic Educational Leadership Program In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Scott Swenson San Francisco April 2018 ABSTRACT Jesuit education has long focused on developing leaders of conscience, competence, and compassion. There is a gap in the literature examining if aspects of the Jesuit charism influence moral development. The Ignatian Identity Survey (IGNIS), and the Defining Issues Test – 2 (DIT-2), were administered to seniors at an all-male Jesuit high school. -

Ignatius, Faber, Xavier:. Welcoming the Gift, Urging

IGNATIUS, FABER, XAVIER:. WELCOMING THE GIFT, Jesuit working group URGING THE MISSION Provinces of Spain “To reach the same point as the earlier ones, or to go farther in our Lord” Const. 81 ent of 1539 was approaching. Ignatius and the first companions know that in putting themselves at the Ldisposition of the Pope, thus fulfilling the vow of Montmartre, the foreseeable apostolic dispersion will put an end to “what God had done with them.” What had God done in them, and why don’t they wish to see it undone? Two lived experiences precede the foundation of the Society which will shape the most intimate desire of the first companions, of their mission and their way of proceeding: the experience of being the experience of being “friends “friends in the Lord” in the Lord” and their way of and their way of helping others by helping others by living and living and preaching preaching “a la apostólica” “a la apostólica” (like (like apostles) apostles). The first expression belongs to St. Ignatius: “Nine of my friends in the Lord have arrived from Paris,” he writes to his friend Juan de Verdolay from Venice in 1537. To what experience of friendship does Ignatius allude? Without a doubt it refers to a human friendship, born of closeness and mutual support, of concern and care for one another, of profound spiritual communication… It also signifies a friendship that roots all its human potential in the Lord as its Source. It is He who has called them freely and personally. He it is who has joined them together as a group and who desires to send NUMBER 112 - Review of Ignatian Spirituality 11 WELCOMING THE GIFT - URGING THE MISSION them out on mission. -

Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back

00621_conversations #26 12/13/13 5:37 PM Page 5 A Remnant and Rebirth Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back By Thomas W. Worcester, S.J. n 2013, for the first time ever, a Jesuit was elected than ten years from entrance as a novice to ordination as a pope. Although this was a first and a surprise, the priest, and then still longer until final vows, the definitive Society of Jesus has always depended on the papa- incorporation of an individual into the Society. But there had cy for its very existence, just as popes have depend- sometimes been diocesan priests who entered, and their for- ed on Jesuits as teachers, scholars, writers, preach- mation would be shorter, allowing them to take up full-time ers, spiritual directors, and missionaries and for work as Jesuits relatively quickly. This also happened in many other roles. Pope Paul III approved the 1814 and beyond. An example is Francesco Finetti Society of Jesus on September 27, 1540; Clement (1762–1842), a well-known Italian preacher who entered the XIV suppressed it on July 21, 1773; Pius VII restored Jesuits in autumn of 1814. He continued his preaching min- it on August 7, 1814. For two centuries no pope has istry as a Jesuit, and among his published works is a sermon reversed Pius VII’s decision, though certain popes, annoyed or he preached in Rome in August 1815 on the theme of St. angered by individual Jesuits or by the Society of Jesus as a Peter in Chains: he compared Pius VII to Peter, and whole, may have given such action some or maybe even a lot Napoleon to the pagan Roman emperors; providence had of thought. -

Are Informationes Ethical?

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/areinformationes294keen IN THE SPIRITUALITY OF JESUITS Are Informationes Ethical? James F. Keenan, S J. 29/4 • SEPTEMBER 1997 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican IPs recom- mendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar wel- comes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclu- sively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Richard J. Clifford, S.J., teaches Old Testament at Weston Jesuit School of Theology in Cambridge, Mass. (1997). Gerald M. Fagin, S.J., teaches theology in the Institute for Ministry at Loyola University, New Orleans, La. (1997). Gerald P. Fogarty, S.J., teaches history in the department of religious studies at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va. (1995). John P. Langan, S.J., as holder of the Kennedy Chair of Christian Ethics, teach- es philosophy at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. -

Jesuit Formation Today: an Invitation to Dialogue and Involvement

STUDIES IN THE SPIRITUALITY OF JESUITS mwk Jesuit Formation Today: An Invitation To Dialogue and Involvement William A. Barry, S.J. NOVEMBER 1988 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican IPs recommendation to religious institutes to recapture the original inspiration of their founders and to adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar welcomes reactions or comments in regard to the material which it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, laity, men and/or women. Hence the Studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclusively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR L. Patrick Carroll, S.J., is pastor of St. Leo's Parish in Tacoma, Washington and superior of the Jesuit community there. John A. Coleman, S.J., teaches Christian social ethics at the Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley. Robert N. Doran, S.J., is one of the editors of the complete works of Bernard Lonergan and teacher of systematic theology at Regis College, the Jesuit School of Theology in Toronto. Philip C. Fischer, S.J., is secretary of the Seminar and an editor at the Institute of Jesuit Sources. -

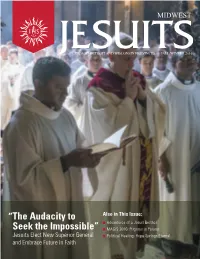

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr. -

Shadowbrook Fire

The SHADOWBROOK FIRE F. X. SHEA ELEPHANT TREE PRESS The SHADOWBROOK FIRE j F. X. Shea Elephant Tree Press 2009 © Copyright, 2009, Society of Jesus of New England Elephant Tree Press 85 School Street Watertown, MA 02471-4251 Design: Circle Graphics All photos, unless otherwise noted, are from the New England Province Archives. Printing: Braintree Printing, Braintree, MA The SHADOWBROOK FIRE j F. X. Shea 1956 j CONTENTS Acknowledgments. i Editor’s Note . .iii Chapter One - The Resort. 1 Chapter Two - The Monkery. 23 Chapter Three - The Last Day . .55 Chapter Four - The Discovery . 72. Chapter Five - The Town . 92 Chapter Six - The Dormitories . .107 Chapter Seven - The Third Floor . 125. Chapter Eight - All But Four. 149 Chapter Nine - The Red Lion. .163 Epilogue. 185 Postscript. .187 Jesuits Assigned to Shadowbrook at the Time of the Fire. 189 Acknowledgements i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book would not have been possible without the much appreciated help of several people: Susan Gussenhoven Shea, who gave crucial assistance at every stage of the project, providing copies of the parts of the manuscript that had not been printed previously and giving permission to use them, answering dozens of questions about Frank Shea’s life and career, and even proofreading the manuscript at the final stage of the project. Alice Poltorick, director of communications for the New England Province of the Jesuits, who oversaw the project from beginning to end and facilitated its completion in numberless ways. Alice Howe, assistant archivist and curator of collections for the New England Province, for providing the photographs used in the book, tracing their provenance, and supplying much useful information about their subjects. -

Jesuits on Mission SOCIETY of JESUS

MARYLAND • NEW ENGLAND • NEW YORK PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2012 Jesuits on Mission SOCIETY OF JESUS Fathers Provincial (from left): Myles Sheehan, SJ, James Shea, SJ, and David Ciancimino, SJ Dear Friends, The Jesuit Conference recently published a newsletter updating the American Jesuits on the process of strategic discernment, by which we are consolidating our Creating the Future 10 provinces into four regional provinces. And, as in any family, the question is often asked, “Are we there yet?” The simple answer is, “No, not yet,” but we are At the regional level, from well on our way. 10 provinces in 2006, we This magazine is one of the common initiatives of the Maryland, New England have embraced a path and New York Provinces. And there are many others: toward four provinces in • a common office for formation; 2021, and provinces are • a common office for vocations; • a common novitiate in Syracuse, N.Y.; working together daily • common events, such as ordinations, jubilees and province days. with an eye toward unifica- By 2015, the New England and New York Provinces should become one, and tion. Province ordinations, by 2020, the addition of the Maryland Province will unify the East Coast of the formation meetings and United States. other gatherings have all On an international level, during the past summer, there was a worldwide meeting taken place across province of Jesuits in Nairobi, Kenya. In this issue, you will read about the experiences of Jesuit Fathers Thomas Benz, Joseph Lingan and Michael McFarland at the Congregation boundaries, creating a more of Procurators. A procurator, in Jesuit tradition, is a province representative who is inclusive environment elected by the members of his province to attend a gathering of representatives from characterized by shared around the world. -

A Remnant and Rebirth: Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back Thomas W

Conversations on Jesuit Higher Education Volume 45 Article 4 April 2014 A Remnant and Rebirth: Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back Thomas W. Worcester S.J. Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/conversations Recommended Citation Worcester, Thomas W. S.J. (2014) "A Remnant and Rebirth: Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back," Conversations on Jesuit Higher Education: Vol. 45, Article 4. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/conversations/vol45/iss1/4 00621_conversations #26 12/13/13 5:37 PM Page 5 Worcester: A Remnant and Rebirth: Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back A Remnant and Rebirth Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back By Thomas W. Worcester, S.J. n 2013, for the first time ever, a Jesuit was elected than ten years from entrance as a novice to ordination as a pope. Although this was a first and a surprise, the priest, and then still longer until final vows, the definitive Society of Jesus has always depended on the papa- incorporation of an individual into the Society. But there had cy for its very existence, just as popes have depend- sometimes been diocesan priests who entered, and their for- ed on Jesuits as teachers, scholars, writers, preach- mation would be shorter, allowing them to take up full-time ers, spiritual directors, and missionaries and for work as Jesuits relatively quickly. This also happened in many other roles. Pope Paul III approved the 1814 and beyond. An example is Francesco Finetti Society of Jesus on September 27, 1540; Clement (1762–1842), a well-known Italian preacher who entered the XIV suppressed it on July 21, 1773; Pius VII restored Jesuits in autumn of 1814. -

The First Five Years Page 12 Getty Images

Spring 2018 Pope Francis: The First Five Years Page 12 Getty Images | Laura Lezza Provincial’s Jesuit Profile Trust in God Unusual Places Donor Profile Guiding the Faithful Letter Page 2 Page 4 Page 6 Page 18 Page 24 Page 26 141155_Mission.indd 159 3/21/18 7:20 PM MEN IN BLACK John Lok From December 27-30, 2017, nearly 50 Jesuits West Scholastics gathered at the Palisades Retreat Center in Federal Way, Wash., for four days of prayer, worship, workshops, and meetings. One of the goals was to foster a greater sense of community amongst the Scholastics who are spread across the country, with a few even continuing their study abroad. They were joined at the meeting by Provincial Father Scott Santarosa, SJ, Socius Father Mike Bayard, SJ, and Provincial Assistant for Formation Father Glen Butterworth, SJ. Mission. Spring 2018 141155_Mission.indd 6243 3/21/18 4:19 PM Jesuits West Spring 2018 Table of Contents MISSION MAGAZINE PROVINCIAL OFFICE Fr. Scott Santarosa, SJ Provincial Page 2 Provincial’s Letter Fr. Mike Bayard, SJ Socius Page 4 Jesuit Profile The whisper that would not go away. ADVANCEMENT OFFICE Siobhán Lawlor Page 6 Trust in God Provincial Assistant for Five senior Jesuits reveal how – even through Advancement and Communication adversity – they learned to trust in God. Fr. John Mossi, SJ Benefactor Relations Page 12 Pope Francis at Five Years Fr. Samuel Bellino, SJ Now five years into his papacy, Pope Francis is Director of Legacy Planning showing his Jesuit DNA. Francine Brown Philanthropy Officer Barbara Gunning Page 18 Unusual Places Senior Philanthropy Officer Jesuits are branching out from their own schools to Kim Randles large public and independent universities. -

Offering a Fragrant Holocaust: a Priesthood of Encounter and Kenosis

Offering a fragrant holocaust: A priesthood of encounter and kenosis Author: Wing Seng Leon Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108279 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2018 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Offering a Fragrant Holocaust: A Priesthood of Encounter and Kenosis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Licentiate in Sacred Theology (S.T.L.) degree from the Boston College School of Theology and Ministry By (Jerome) Wing Seng Leon, SJ Supervisor: Prof. John Baldovin, SJ Reader: Prof. Thomas Stegman, SJ August 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Priesthood and the Society of Jesus ............................................................................................ 1 Objectives of this Thesis ............................................................................................................. 4 History............................................................................................................................................. 7 The Church, the Priesthood and the Estrangement in the Early Modern Period ........................ 8 Ignatius of Loyola and the Foundations of the Order ............................................................... 14 Preti Reformati – The Orders of Clerk