Are Informationes Ethical?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography on the History of the Jesuits : Publications in English

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/bibliographyonhi281begh . H nV3F mm Ǥffi fitwffii 1 unBK i$3SOul nt^ni^1 ^H* an I A'. I ' K&lfi HP HHBHHH b^SHs - HHHH hHFJISi i *^' i MPiUHraHHHN_ ^ 4H * ir Til inrlWfif O'NEILL UBRAHJ BOSTON COLLEGE Bibliography on the History of the \ Jesuits Publications in English, 1900-1993 Paul Begheyn, S.J. CD TtJ 28/1 JANUARY 1996 ft THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican IPs recom- mendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar wel- comes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclu- sively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR George M. Anderson, S.J., is associate editor of America, in New York, and writes regularly on social issues and the faith (1993). Peter D. Byrne, S.J., is rector and president of St. -

Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 4-2018 Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit Charism and Students' Moral Judgement Scott weS nson University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons Recommended Citation Swenson, Scott, "Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit Charism and Students' Moral Judgement" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 453. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/453 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STUDENTS’ PERCEPTIONS OF THE JESUIT CHARISM AND STUDENTS’ MORAL JUDGEMENT A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Department of Leadership Studies Catholic Educational Leadership Program In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Scott Swenson San Francisco April 2018 ABSTRACT Jesuit education has long focused on developing leaders of conscience, competence, and compassion. There is a gap in the literature examining if aspects of the Jesuit charism influence moral development. The Ignatian Identity Survey (IGNIS), and the Defining Issues Test – 2 (DIT-2), were administered to seniors at an all-male Jesuit high school. -

Extraordinary Awards

EXTRAORDINARY AWARDS Upon recommendation of the faculty, the school Awards Committee and the Senior class, JESUIT HIGH SCHOOL is privileged to recognize the excellence of outstanding individuals in the Class of 2016. THE SALUTATORIAN AWARD is given to the Senior chosen to open the Commencement Exer- cises with an invocation for his classmates and friends........................................... Nicholas P. Austin THE SCHOLAR-ATHLETE AWARDS are given to those Seniors who have consistently maintained a high grade point average and who have contributed significantly to the athletic program of Jesuit High School. ................................................................................ Nathaniel A. Huck, Sean T. Kurdy THE SCHOLAR-ARTIST AWARD is given to the Senior who has consistently maintained a high grade point average and who has contributed significantly to the visual and performing arts program of Jesuit High School. ..................................................................................................John P. Novotny THE PEDRO ARRUPE, S.J., AWARD is given to the Senior who has excelled in his concern for Christian social justice. ........................................................................................... Christian G. Flores THE ALOYSIUS GONZAGA, S.J., AWARDS, named after the Jesuit patron saint of students, are given to those Seniors who, in the spirit of the magis, have demonstrated extraordinary achievement in Jesuit’s academic program. ...............................................Alexander -

Ignatius, Faber, Xavier:. Welcoming the Gift, Urging

IGNATIUS, FABER, XAVIER:. WELCOMING THE GIFT, Jesuit working group URGING THE MISSION Provinces of Spain “To reach the same point as the earlier ones, or to go farther in our Lord” Const. 81 ent of 1539 was approaching. Ignatius and the first companions know that in putting themselves at the Ldisposition of the Pope, thus fulfilling the vow of Montmartre, the foreseeable apostolic dispersion will put an end to “what God had done with them.” What had God done in them, and why don’t they wish to see it undone? Two lived experiences precede the foundation of the Society which will shape the most intimate desire of the first companions, of their mission and their way of proceeding: the experience of being the experience of being “friends “friends in the Lord” in the Lord” and their way of and their way of helping others by helping others by living and living and preaching preaching “a la apostólica” “a la apostólica” (like (like apostles) apostles). The first expression belongs to St. Ignatius: “Nine of my friends in the Lord have arrived from Paris,” he writes to his friend Juan de Verdolay from Venice in 1537. To what experience of friendship does Ignatius allude? Without a doubt it refers to a human friendship, born of closeness and mutual support, of concern and care for one another, of profound spiritual communication… It also signifies a friendship that roots all its human potential in the Lord as its Source. It is He who has called them freely and personally. He it is who has joined them together as a group and who desires to send NUMBER 112 - Review of Ignatian Spirituality 11 WELCOMING THE GIFT - URGING THE MISSION them out on mission. -

SJ Liturgical Calendar

SOCIETY OF JESUS PROPER CALENDAR JANUARY 3 THE MOST HOLY NAME OF JESUS, Titular Feast of the Society of Jesus Solemnity 19 Sts. John Ogilvie, Priest; Stephen Pongrácz, Melchior Grodziecki, Priests, and Mark of Križevci, Canon of Esztergom; Bl. Ignatius de Azevedo, Priest, and Companions; James Salès, Priest, and William Saultemouche, Religious, Martyrs FEBRUARY 4 St. John de Brito, Priest; Bl. Rudolph Acquaviva, Priest, and Companions, Martyrs 6 Sts. Paul Miki, Religious, and Companions; Bl. Charles Spinola, Sebastian Kimura, Priests, and Companions; Peter Kibe Kasui, Priest, and Companions, Martyrs Memorial 15 St. Claude La Colombière, Priest Memorial MARCH 19 ST. JOSEPH, SPOUSE OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY, Patron Saint of the Society of Jesus Solemnity APRIL 22 THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY, MOTHER OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS Feast 27 St. Peter Canisius, Priest and Doctor of the Church Memorial MAY 4 St. José María Rubio, Priest 8 Bl. John Sullivan, Priest 16 St. Andrew Bobola, Priest and Martyr 24 Our Lady of the Way JUNE 8 St. James Berthieu, Priest and Martyr Memorial 9 St. Joseph de Anchieta, Priest 21 St. Aloysius Gonzaga, Religious Memorial JULY 2 Sts. Bernardine Realino, John Francis Régis and Francis Jerome; Bl. Julian Maunoir and Anthony Baldinucci, Priests 9 Sts. Leo Ignatius Mangin, Priest, Mary Zhu Wu and Companions, Martyrs Memorial 31 ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA, Priest and Founder of the Society of Jesus Solemnity AUGUST 2 St. Peter Faber, Priest 18 St. Alberto Hurtado Cruchaga, Priest Memorial SEPTEMBER 2 Bl. James Bonnaud, Priest, and Companions; Joseph Imbert and John Nicolas Cordier, Priests; Thomas Sitjar, Priest, and Companions; John Fausti, Priest, and Companions, Martyrs 9 St. -

Saint John Francis Regis - June 16Th

Saint John Francis Regis - June 16th Born 31 January 1597 France Died 31 December 1640 France At 19, Saint Regis entered the Jesuit order and began to prepare for a priestly ministry that would save thousands of souls. He was ordained at the age of 34 and was then sent to the mission fields of France. In the years since the Protestant Reformation, many French Catholics had become Protestant. Still others were so disillusioned by the Wars of Religion, that they had abandoned Christian faith, entirely. During Regis' day, parishes were known not to have administered the sacraments for twenty years. Many towns were entirely without priests and many of the priests who remained were woefully ill-educated and often ordained hurriedly in order to replace the thousands who had been martyred. During this turbulent period, countless women were forced into prostitution because they had no other recourse for survival. Seeing the need to step in, Saint Regis, began to minister to prostitutes whenever possible, pounding on brothel doors and demanding that new “recruits” be given into his custody. Sometimes, he would see a woman being dragged off by an attacker and would throw himself upon the man, pulling the woman from the grasp of her assailant and allowing himself to be beaten instead. He established safe houses for these at-risk women, whom he came to call “Daughters of Refuge”. Training in lacemaking and embroidery were provided at these locations, giving an alternate income to support the wayward. In addition, St. Regis founded a group of charitable women that helped feed many of the women and orphans during their transition into a productive life, and extended his protection by demanding and receiving, treatment for these abandoned victims of human trafficking, from doctors, nurses and pharmacists. -

Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back

00621_conversations #26 12/13/13 5:37 PM Page 5 A Remnant and Rebirth Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back By Thomas W. Worcester, S.J. n 2013, for the first time ever, a Jesuit was elected than ten years from entrance as a novice to ordination as a pope. Although this was a first and a surprise, the priest, and then still longer until final vows, the definitive Society of Jesus has always depended on the papa- incorporation of an individual into the Society. But there had cy for its very existence, just as popes have depend- sometimes been diocesan priests who entered, and their for- ed on Jesuits as teachers, scholars, writers, preach- mation would be shorter, allowing them to take up full-time ers, spiritual directors, and missionaries and for work as Jesuits relatively quickly. This also happened in many other roles. Pope Paul III approved the 1814 and beyond. An example is Francesco Finetti Society of Jesus on September 27, 1540; Clement (1762–1842), a well-known Italian preacher who entered the XIV suppressed it on July 21, 1773; Pius VII restored Jesuits in autumn of 1814. He continued his preaching min- it on August 7, 1814. For two centuries no pope has istry as a Jesuit, and among his published works is a sermon reversed Pius VII’s decision, though certain popes, annoyed or he preached in Rome in August 1815 on the theme of St. angered by individual Jesuits or by the Society of Jesus as a Peter in Chains: he compared Pius VII to Peter, and whole, may have given such action some or maybe even a lot Napoleon to the pagan Roman emperors; providence had of thought. -

St. John Francis Regis 8Am, 5Pm Vigil August 8Th, 2021 19Th Sunday in Ordinary Time Monday-Thursday 7Am & 8Am AUGUST 8TH, 2021

Mass Times Sunday 7am, 9am, 11:30am Saturday St. John Francis Regis 8am, 5pm Vigil August 8th, 2021 19th Sunday in Ordinary Time Monday-Thursday 7am & 8am AUGUST 8TH, 2021 Friday 7am & 8:45am Holy Days of Obligation 7am, 9am, 7pm Confessions Saturday Before, during, and following the 5pm Mass (starting at 4pm) Sunday During all Sunday Masses *Also by appointment Rosary Monday-Friday 7:30am Clergy School Religious Education Saturday Pastor 4:30pm Director of Religious Rev. Raymond F. Schmidt Principal [email protected] Education Sunday Susan McDonough Rich Olon 6:30am Parochial Vicar Grades PK-8 – Before & After Care [email protected] 43900 St John’s Road, Hollywood, MD Rev. Nicholas Morrison [email protected] 20636 Sunday Classes PARISH Grades K-6 and 8-12 Pastoral Associate Phone: 301-373-2142 STAFF 10:15am-11:15am Deacon Ammon Ripple Fax: 301-373-4500 Tuesday Classes Deacon Ken Scheiber Website: sjshollywood.org Music Ministry Grades 5-8 Seminarians Email: [email protected] Jonathan Hellerman 7pm-8:15pm Brother Thomas Mary Wagaman O.P. [email protected] Deacon Kyle Vance The program usually starts in Admin. Assistant John Winslow September and ends in May. Diana Huber Jessiah Rojas [email protected] Finance Manager Dawn Papp Mailing Address: 43950 St John’s Road, Hollywood, MD 20636 [email protected] Physical Address: 43927 St John’s Road, Hollywood, MD 20636 Secretary Phone: 301-373-2281 Fax: 301-373-8984 Website: saintjohnsparishhollywood.org Facebook: www.facebook.com/sjchollywood/ Twitter: @sjchollywood Mary Pat Kirk [email protected] MISSION STATEMENT The mission of St. John Francis Regis Parish is to foster a family of faith, Office Hours built on yesterday’s foundation, so that today’s spirituality, service, and education Tuesday-Friday: 9:30am-4:30pm will continue to grow into tomorrow’s Catholic community. -

NEW PARISHIONERS.St. Aloysius Extends a Warm Welcome to All Who

22800 Washington Street PO Box 310 Leonardtown, MD 20650 Rectory (301) 475V8064 Fax (301) 475V8762 NEW PARISHIONERS…St. Aloysius extends a warm welcome to March 14, 2021 all who are joining us for prayer, worship, or instruction. If you are new to the area or returning home to the Church, we invite you to Fourth Sunday of Lent register and make St. Aloysius your parish. Registration forms can be obtained at the church, on our website, or by calling the rectory. SCHEDULE OF SERVICES MASS SCHEDULE: FIND A SMALL GROUP… Find Small Group Faith Formation opportunities in our area for both adults and high school teens by Saturday: 5:00 pm visiting www.ConnectStMarys.com. Sunday: 8:00 am and 11:00 am Daily: 12:15 pm Tuesday & Thursday RITE OF CHRISTIAN INITIATION OF ADULTS (RCIA)...RCIA is the process of welcoming new members to the 8:30 am Wednesday & Friday Catholic Church. It is intended for adults who have never been 7:30 am Saturday baptized or for adults who have been baptized Christian and now wish to practice the faith in the Catholic tradition. It is an ongoing HOLY DAY MASSES: process of formation, catechesis and liturgical rites. Anyone As Announced inside the Bullen. interested is asked to call the rectory to discuss the process. EUCHARISTIC ADORATION: 7 days a week: 6:30R7:30 AM and PM SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM…Parents are asked to call the parish office to register for the Baptismal Preparation Meeting and for the FIRST FRIDAYS: Mass at 8:30 am baptism of their child. -

Jesuit Formation Today: an Invitation to Dialogue and Involvement

STUDIES IN THE SPIRITUALITY OF JESUITS mwk Jesuit Formation Today: An Invitation To Dialogue and Involvement William A. Barry, S.J. NOVEMBER 1988 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican IPs recommendation to religious institutes to recapture the original inspiration of their founders and to adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar welcomes reactions or comments in regard to the material which it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, laity, men and/or women. Hence the Studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclusively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR L. Patrick Carroll, S.J., is pastor of St. Leo's Parish in Tacoma, Washington and superior of the Jesuit community there. John A. Coleman, S.J., teaches Christian social ethics at the Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley. Robert N. Doran, S.J., is one of the editors of the complete works of Bernard Lonergan and teacher of systematic theology at Regis College, the Jesuit School of Theology in Toronto. Philip C. Fischer, S.J., is secretary of the Seminar and an editor at the Institute of Jesuit Sources. -

St. John Francis Regis Catholic Church Diocese of Lafayette, Established 1853 232 Main Street — P

St. John Francis Regis Catholic Church Diocese of Lafayette, Established 1853 232 Main Street — P. O. Box 649, Arnaudville LA 70512-0649 (337) 754-5912 · Fax (337) 754-7203 . www.arnaudvillecatholic.org Rev. Travis Abadie, Pastor WEEKEND MASSES Deacon Stephen Van Cleve Saturday 4:00 pm Deacon Ken Arnaud (retired) Sunday 7:00 am & 10:30 am Betty Sanders, Office Manager Sheila Gresko, Director of Religious Education WEEKEND MASSES AT ST. CATHERINE Huey Wyble, II St. Therese Thrift Shop Manager./Activities Dir. Saturday 6:00 pm Willie Wyble, Maintenance Sunday 8:30 am PARISH OFFICE HOURS WEEKDAY MASSES @ ST. FRANCIS Monday thru Thursday 9:00 am to 2:00 pm (open during lunch hour) Wednesday: 6:00 pm w/Adoration 4:30-5:25pm Closed on Fridays Friday: 8:30 am w/Adoration 7:00-8:25am SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION St. John Francis Regis Church: WEEKDAY MASSES @ ST. CATHERINE Fridays 8:00am-8:20am Monday: 8:30 am w/Adoration 7:00-8:25am Saturdays 2:00pm-3:00pm, Thursday: 8:30 am w/Adoration 7:00-8:25am Sundays immediately before 10:30am Mass, St. Catherine Church: Monday & Thursdays 8:00am-8:20am OTHER DEVOTIONS: SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM DAILY: Adoration Chapel Classes by appointment @ Church office Call office during pregnancy to register for class. MONDAY: Marian Movement for Priests, 8:00 am; French Rosary & Choir La Chorale de Saint Michael @ JMMNH @ SACRAMENT OF MARRIAGE 4pm Call no less than six months prior to the anticipated date of marriage. WEDNESDAY: St. Michael Rosary Group, 9:00 am ANOINTING OF THE SICK THURSDAY: Our Lady of Fatima Rosary Group, 9:30 am; Please call at the beginning of an illness. -

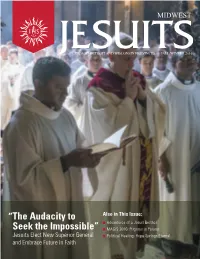

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr.