Offering a Fragrant Holocaust: a Priesthood of Encounter and Kenosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOHN W. O·Malley, SJ JESUIT SCHOOLS and the HUMANITIES

JESUIT SCHOOLS AND THE HUMANITIES YESTERDAY AND TODAY -2+1:2·0$//(<6- ashington, D.C. 20036-5727 635,1* Jesuit Conference, Inc. 1016 16th St. NW Suite 400 W SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION, EFFECTIVE JANUARY 2015 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY The Seminar is composed of a number of Jesuits appointed from their prov- U.S. JESUITS inces in the United States. An annual subscription is provided by the Jesuit Conference for U.S. Jesuits living in the United The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice States and U.S. Jesuits who are still members of a U.S. Province but living outside the United of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and gathers current scholarly stud- States. ies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. ALL OTHER SUBSCRIBERS It then disseminates the results through this journal. All subscriptions will be handled by the Business Office U.S.: One year, $22; two years, $40. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, other Canada and Mexico: One year, $30; two years, $52. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) priests, religious, and laity. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclusively for them. Others who may find them Other destinations: One year: $34; two years, $60. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) helpful are cordially welcome to read them at: [email protected]/jesuits . ORDERING AND PAYMENT Place orders at www.agrjesuits.com to receive Discount CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR If paying by check - Make checks payable to: Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality Payment required at time of ordering and must be made in U.S. -

Bibliography on the History of the Jesuits : Publications in English

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/bibliographyonhi281begh . H nV3F mm Ǥffi fitwffii 1 unBK i$3SOul nt^ni^1 ^H* an I A'. I ' K&lfi HP HHBHHH b^SHs - HHHH hHFJISi i *^' i MPiUHraHHHN_ ^ 4H * ir Til inrlWfif O'NEILL UBRAHJ BOSTON COLLEGE Bibliography on the History of the \ Jesuits Publications in English, 1900-1993 Paul Begheyn, S.J. CD TtJ 28/1 JANUARY 1996 ft THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican IPs recom- mendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar wel- comes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclu- sively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR George M. Anderson, S.J., is associate editor of America, in New York, and writes regularly on social issues and the faith (1993). Peter D. Byrne, S.J., is rector and president of St. -

Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 4-2018 Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit Charism and Students' Moral Judgement Scott weS nson University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons Recommended Citation Swenson, Scott, "Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit Charism and Students' Moral Judgement" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 453. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/453 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STUDENTS’ PERCEPTIONS OF THE JESUIT CHARISM AND STUDENTS’ MORAL JUDGEMENT A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Department of Leadership Studies Catholic Educational Leadership Program In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Scott Swenson San Francisco April 2018 ABSTRACT Jesuit education has long focused on developing leaders of conscience, competence, and compassion. There is a gap in the literature examining if aspects of the Jesuit charism influence moral development. The Ignatian Identity Survey (IGNIS), and the Defining Issues Test – 2 (DIT-2), were administered to seniors at an all-male Jesuit high school. -

Manresa and Saint Ignatius of Loyola

JOAN SEGARRA PIJUAN was born in Tárrega, Spain on June 29, 1926. He joined the Society of Jesus in 1942. Seventeen years later he completed his religious and cultural education. On July 29, 1956 – in the Year of Saint Ignatius – he was ordained at the cathedral in Manresa. He has spent much of his life in Veruela, Bar- celona, Sant Cugat del Vallès, Palma (Majorca), Raimat, Rome and Man- resa and has also lived in a number of countries in Central and South Ameri- ca, Africa and Europe. He has always been interested in spi- ritual theology and the study of Saint Ignatius of Loyola. SAINT IGNA- TIUS AND MANRESA describes the Saint’s sojourn here in a simple, rea- dable style. The footnotes and exten- sive bibliography will be of particular interest to scholars wishing the study the life of St. Ignatius in greater de- tail. This book deals only with the months Saint Ignatius spent in Man- resa, which may have been the most interesting part of his life: the months of his pilgrimage and his mystical en- lightenments. Manresa is at the heart of the Pilgrim’s stay in Catalonia because “between Ignatius and Man- resa there is a bond that nothing can break” (Torras y Bages). A copy of this book is in the Library at Stella Maris Generalate North Foreland, Broadstairs, Kent, England CT10 3NR and is reproduced on line with the permission of the author. AJUNTAMENT DE MANRESA Joan Segarra Pijuan, S.J. 1st edition: September 1990 (Catalan) 2nd edition: May 1991 (Spanish) 3rd edition: September 1992 (English) © JOAN SEGARRA i PIJUAN, S.J. -

Ignatius, Faber, Xavier:. Welcoming the Gift, Urging

IGNATIUS, FABER, XAVIER:. WELCOMING THE GIFT, Jesuit working group URGING THE MISSION Provinces of Spain “To reach the same point as the earlier ones, or to go farther in our Lord” Const. 81 ent of 1539 was approaching. Ignatius and the first companions know that in putting themselves at the Ldisposition of the Pope, thus fulfilling the vow of Montmartre, the foreseeable apostolic dispersion will put an end to “what God had done with them.” What had God done in them, and why don’t they wish to see it undone? Two lived experiences precede the foundation of the Society which will shape the most intimate desire of the first companions, of their mission and their way of proceeding: the experience of being the experience of being “friends “friends in the Lord” in the Lord” and their way of and their way of helping others by helping others by living and living and preaching preaching “a la apostólica” “a la apostólica” (like (like apostles) apostles). The first expression belongs to St. Ignatius: “Nine of my friends in the Lord have arrived from Paris,” he writes to his friend Juan de Verdolay from Venice in 1537. To what experience of friendship does Ignatius allude? Without a doubt it refers to a human friendship, born of closeness and mutual support, of concern and care for one another, of profound spiritual communication… It also signifies a friendship that roots all its human potential in the Lord as its Source. It is He who has called them freely and personally. He it is who has joined them together as a group and who desires to send NUMBER 112 - Review of Ignatian Spirituality 11 WELCOMING THE GIFT - URGING THE MISSION them out on mission. -

Address of Pope Paul VI to General Congregation 32 (1974)

Address of Pope Paul VI to General Congregation 32 (1974) Pope Paul VI addressed the delegates to the 32nd General Congregation on December 3, 1974, noting similar “joy and trepidation” to when the last congregation began nearly a decade before. Looking to the assembled Jesuits, the pontiff declares, “there is in you and there is in us the sense of a moment of destiny for your Society.” Indeed, “in this hour of anxious expectation and of intense attention ‘to what the Spirit is saying’ to you and to us,” Paul VI asks the delegates to answer: “Where do you come from?” “Who are you?” “Where are you going?” Esteemed and beloved Fathers of the Society of Jesus, As we receive you today, there is renewed for us the joy and trepidation of May 7, 1965, when the Thirty-first General Congregation of your Society began, and that of November 15 of the following year, at its conclusion. We have great joy because of the outpouring of sincere paternal love which every meeting between the Pope and the sons of St. Ignatius cannot but stir up. This is especially true because we see the witness of Christian apostolate and of fidelity which you give us and in which we rejoice. But there is also trepidation for the reasons of which we shall presently speak to you. The inauguration of the 32nd General Congregation is a special event, and it is usual for us to have such a meeting on an occasion like this; but this meeting has a far wider and more historic significance. -

Daniello Bartoli Sj (1608–85) and the Uses of Global History*

This is a repository copy of Baroque around the clock: : Daniello Bartoli SJ (1608-1685) and the uses of global history. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/177761/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Ditchfield, Simon Richard orcid.org/0000-0003-1691-0271 (Accepted: 2021) Baroque around the clock: : Daniello Bartoli SJ (1608-1685) and the uses of global history. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 1. pp. 1-31. ISSN 0080-4401 (In Press) Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 BAROQUE AROUND THE CLOCK: DANIELLO BARTOLI SJ (1608–85) AND THE USES OF GLOBAL HISTORY* By Simon Ditchfield READ 18 SEPTEMBER 2020 ABSTRACT: Right from its foundation in 1540, the Society of Jesus realised the value and role of visual description (ekphrasis) in the persuasive rhetoric of Jesuit missionary accounts. Over a century later, when Jesuit missions were to be found on all the inhabited continents of the world then known to Europeans, descriptions of these new found lands were to be read for entertainment as well as the edification of their Old World audiences. -

Book Reviews ∵

journal of jesuit studies 4 (2017) 99-183 brill.com/jjs Book Reviews ∵ Thomas Banchoff and José Casanova, eds. The Jesuits and Globalization: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Challenges. Washington, dc: Georgetown University Press, 2016. Pp. viii + 299. Pb, $32.95. This volume of essays is the outcome of a three-year project hosted by the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University which involved workshops held in Washington, Oxford, and Florence and cul- minated in a conference held in Rome (December 2014). The central question addressed by the participants was whether or not the Jesuit “way of proceeding […] hold[s] lessons for an increasingly multipolar and interconnected world” (vii). Although no fewer than seven out of the thirteen chapters were authored by Jesuits, the presence amongst them of such distinguished scholars as John O’Malley, M. Antoni Üçerler, Daniel Madigan, David Hollenbach, and Francis Clooney as well as of significant historians of the Society such as Aliocha Mal- davsky, John McGreevy, and Sabina Pavone together with that of the leading sociologist of religion, José Casanova, ensure that the outcome is more than the sum of its parts. Banchoff and Casanova make it clear at the outset: “We aim not to offer a global history of the Jesuits or a linear narrative of globaliza- tion but instead to examine the Jesuits through the prism of globalization and globalization through the prism of the Jesuits” (2). Accordingly, the volume is divided into two, more or less equal sections: “Historical Perspectives” and “Contemporary Challenges.” In his sparklingly incisive account of the first Jesuit encounters with Japan and China, M. -

Following the Way of Ignatius, Francis Xavier and Peter Faber,Servants Of

FOLLOWING THE WAY OF IGNATIUS, FRANCIS XAVIER AND PETER FABER, SERVANTS OF CHRIST’S MISSION* François-Xavier Dumortier, S.J. he theme of this meeting places us in the perspective of the jubilee year, which recalls to us the early beginnings of the Society of Jesus. What is the aim of thisT jubilee year? It is not a question simply of visiting the past as one does in a museum but of finding again at the origin of our history, that Divine strength which seized some men – those of yesterday and us today – to make them apostles. It is not even a question of stopping over our beginnings in Paris, in 1529, when Ignatius lodged in the same room with Peter Faber and Francis-Xavier: it is about contemplating and considering this unforeseeable and unexpected meeting where this group of companions, who became so bonded together by the love of Christ and for “the sake of souls”, was born by the grace of God. And finally it is not a question of reliving this period as if we were impelled solely by an intellectual curiosity, or by a concern to give an account of our history; it is about rediscovering through Ignatius, Francis-Xavier and Peter Faber this single yet multiple face of the Society, those paths that are so vibrantly personal and their common, resolute desire to become “companions of Jesus”, to be considered “servants” of The One who said, “I no longer call you servants… I call you friends” (Jn. 15,15) Let us look at these three men so very different in temperament that everything about them should have kept them apart one from another – but also so motivated by the same desire to “search and find God”. -

THE PROCESSIONS in GOD Sr

Teachings of SCTJM - Sr. Rachel Marie Gosda, SCTJM HE IS ALL IN ALL:THE PROCESSIONS IN GOD Sr. Rachel Marie Gosda, SCTJM April 6, 2013 The truth that God is one and also triune has been communicated to us through Divine Revelation. However, the way in which the Church has attempted to explain this great mystery has been the labor of the centuries. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches, “In order to articulate the dogma of the Trinity, the Church had to develop her own terminology with the help of certain notions of philosophical origin: ‘substance’, ‘person’ or ‘hypostasis’, ‘relation’ and so on. In doing this, she did not submit the faith to human wisdom, but gave a new and unprecedented meaning to these terms.”1 The “and so on” indicated here by the Catechism can include one more term, which we shall examine in this reflection: procession. We understand this term to mean the origin of one from another.2 Most of this reflection will deal with the nature and relationship of the two processions which exist in God: that of the Son and the Holy Spirit. In order to arrive at this point, however, let us begin from a more foundational starting-point by considering what exactly “procession” is in God. St. Thomas Aquinas teaches that because God is above all things, anything that we say of Him based on some likeness that we see in creatures is but a representation of who He truly is. Therefore, any comparison that we draw from creatures to God must not be limited to the level of the creature, but must be expanded to the level of the highest creatures, intellectual substances (as God is in the most perfect degree).3 So it is that, although all procession involves some sort of action, this action cannot be considered uniformly between creatures and God. -

Forgotten Saint: the Life and Writings of Alfonso Salmerón, SJ

Forgotten Saint: The Life and Writings of Alfonso Salmerón, SJ Sam Z. Conedera, SJ 52/4 WINTER 2020 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY ѡѢёіђѠȱіћȱѡѕђȱѝіџіѡѢюљіѡѦȱќѓȱ ђѠѢіѡѠȱȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱ ȱȱȱȱȱǯ ȱȱȱ ȱ¢ȱȱȱȱ ȱȱȱȱ ǯȱȱȱęȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱȱȱ ǰȱ¢ȱȱȱȱ ǰȱȱ- ȱȱ¢ȱȱȱȱȱ¢ȱȱȱȱ ȱ ȱȱ ǯȱ ȱȱȱȱȱȱȱǯ ȱ ȱ ¡ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ǯȱ ȱ ȱȱȱѡѢёіђѠȱ¢ȱȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱȱȱ ȱȱȱǰȱ¢ǰȱȱ¢ǯȱȱ ȱęȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱȱȱȱDZȱȓǯȦǯ CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR DZȱȱȱ¢ȱȱ¢ȱȱȱȱǯ Casey C. Beaumier, SJǰȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱȱ ȱ- ǰȱȱ ǰȱǯȱǻŘŖŗŜǼ Brian B. Frain, SJ,ȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ ǯȱȱȱȱȱȱ¢ȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ ȱ¢ȱȱ ȱ¢ǰȱǯȱǻŘŖŗŞǼ Barton T. Geger, SJǰȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱѡѢёіђѠDzȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱȱ ȱȱȱ ȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱȱȱȱ¢ȱȱ¢ȱȱȱǯȱǻŘŖŗřǼ Michael Knox, SJǰȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ ȱ¢ȱȱȱ ȱǰȱǰȱȱȱȱȱȱȱǯȱǻŘŖŗŜǼ William A. McCormick, SJ,ȱȱȱȱȱ¢ȱȱȱ ȱȱȱȱ¢ǯȱǻŘŖŗşǼ Gilles Mongeau, SJ,ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ¢ȱ ǯȱ ȱ ȱ ¢ȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱǯȱǻŘŖŗŝǼ Peter P. Nguyen, SJ,ȱ ȱȱ ȱ ȱ ¢ȱ ȱ ȱ ¢ȱȱǰȱǯȱǻŘŖŗŞǼ John R. Sachs, SJ,ȱȱȱȱ £ȱȱȱȱ ȱȱ ǰȱǰȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ Theological StudiesǯȱǻŘŖŗŚǼ ¢ȱȚȱŘŖŘŖȱȱȱ¢ȱȱ ȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱǯ ȱŗŖŞŚȬŖŞŗř ќџєќѡѡђћȱюіћѡDZȱ ѕђȱіѓђȱюћёȱџіѡіћєѠȱќѓȱ љѓќћѠќȱюљњђџңћǰȱ ȱǯȱǰȱ ȱȱ ȱȱ ȱȱ ȱȱȱȱ ȱ śŘȦŚȱȱȱȱȱyȱȱȱȱȱ ȱŘŖŘŖ a word from the editor… Nicholas Bobadilla (1511–1590) and Simão Rodrigues (1510–1579), not St. Francis Xavier (1506–1552), were supposed to go to India. Their mis- sion came in response to a request by King John III of Portugal (1502– 1557), who had asked Ignatius for several Jesuits to convert the peoples in his colonial empire. Ignatius’s initial choices did not pan out. Bobadilla fell seriously ill, so Ignatius turned to his dear friend Xavier, who is said to have replied with a free and simple, “Here I am.” But when Xavier and Rodrigues arrived at the royal court, they impressed the king so much that he asked Rodrigues to remain and work in Portugal instead. -

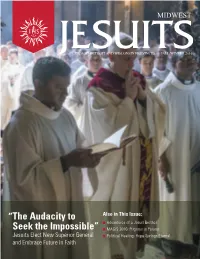

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr.