Maya Medicine in the Biological Gaze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Toltec Invasion and Chichen Itza

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: Breaking the Maya Code Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs Angkor and the Khmer Civilization India: A Short History The Incas The Aztecs See our websites www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com 7 THE POSTCLASSIC By the close of the tenth century AD the destiny of the once proud and independent Maya had, at least in northern Yucatan, fallen into the hands of grim warriors from the highlands of central Mexico, where a new order of men had replaced the supposedly more intellectual rulers of Classic times. We know a good deal about the events that led to the conquest of Yucatan by these foreigners, and the subsequent replacement of their state by a resurgent but already decadent Maya culture, for we have entered into a kind of history, albeit far more shaky than that which was recorded on the monuments of the Classic Period. The traditional annals of the peoples of Yucatan, and also of the Guatemalan highlanders, transcribed into Spanish letters early in Colonial times, apparently reach back as far as the beginning of the Postclassic era and are very important sources. But such annals should be used with much caution, whether they come to us from Bishop Landa himself, from statements made by the native nobility, or from native lawsuits and land claims. These are often confused and often self-contradictory, not least because native lineages seem to have deliberately falsified their own histories for political reasons. Our richest (and most treacherous) sources are the K’atun Prophecies of Yucatan, contained in the “Books of Chilam Balam,” which derive their name from a Maya savant said to have predicted the arrival of the Spaniards from the east. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Jantzen on Wempe. Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations

H-German Jantzen on Wempe. Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations. Discussion published by Jennifer Wunn on Wednesday, May 26, 2021 Review published on Friday, May 21, 2021 Author: Sean Andrew Wempe Reviewer: Mark Jantzen Jantzen on Wempe, 'Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations' Sean Andrew Wempe. Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. 304 pp. $78.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-19-090721-1. Reviewed by Mark Jantzen (Bethel College)Published on H-Nationalism (May, 2021) Commissioned by Evan C. Rothera (University of Arkansas - Fort Smith) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=56206 Demise or Transmutation for a Unique National Identity? Sean Andrew Wempe’s investigation of the afterlife in the 1920s of the Germans who lived in Germany’s colonies challenges a narrative that sees them primarily as forerunners to Nazi brutality and imperial ambitions. Instead, he follows them down divergent paths that run the gamut from rejecting German citizenship en masse in favor of South African papers in the former German Southwest Africa to embracing the new postwar era’s ostensibly more liberal and humane version of imperialism supervised by the League of Nations to, of course, trying to make their way in or even support Nazi Germany. The resulting well-written, nuanced examination of a unique German national identity, that of colonial Germans, integrates the German colonial experience into Weimar and Nazi history in new and substantive ways. -

Centeredness As a Cultural and Grammatical Theme in Maya-Mam

CENTEREDNESS AS A CULTURAL AND GRAMMATICAL THEME IN MAYA-MAM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Wesley M. Collins, B.S., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Examination Committee: Approved by Professor Donald Winford, Advisor Professor Scott Schwenter Advisor Professor Amy Zaharlick Department of Linguistics Copyright by Wesley Miller Collins 2005 ABSTRACT In this dissertation, I look at selected Maya-Mam anthropological and linguistic data and suggest that they provide evidence that there exist overlapping cultural and grammatical themes that are salient to Mam speakers. The data used in this study were gathered largely via ethnographic methods based on participant observation over my twenty-five year relationship with the Mam people of Comitancillo, a town of 60,000 in Guatemala’s Western Highlands. For twelve of those years, my family and I lived among the Mam, participating with them in the cultural milieu of daily life. In order to help shed light on the general relationship between language and culture, I discuss the key Mayan cultural value of centeredness and I show how this value is a pervasive organizing principle in Mayan thought, cosmology, and daily living, a value called upon by the Mam in their daily lives to regulate and explain behavior. Indeed, I suggest that centeredness is a cultural theme, a recurring cultural value which supersedes social differences, and which is defined for cultural groups as a whole (England, 1978). I show how the Mam understanding of issues as disparate as homestead construction, the town central plaza, historical Mayan religious practice, Christian conversion, health concerns, the importance of the numbers two and four, the notions of agreement and forgiveness, child discipline, and moral stance are all instantiations of this basic underlying principle. -

An Analysis of Palestinian and Native American Literature

INDIGENOUS CONTINUANCE THROUGH HOMELAND: AN ANALYSIS OF PALESTINIAN AND NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE ________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University ________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English ________________________________________ by Alana E. Dakin June 2012 Dakin 2 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of English ____________________ Dr. George Hartley Professor, English Thesis Advisor ____________________ Dr. Carey Snyder Honors Tutorial College, Director of Studies English ____________________ Dr. Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College Dakin 3 CHAPTER ONE Land is more than just the ground on which we stand. Land is what provides us with the plants and animals that give us sustenance, the resources to build our shelters, and a place to rest our heads at night. It is the source of the most sublime beauty and the most complete destruction. Land is more than just dirt and rock; it is a part of the cycle of life and death that is at the very core of the cultures and beliefs of human civilizations across the centuries. As human beings began to navigate the surface of the earth thousands of years ago they learned the nuances of the land and the creatures that inhabited it, and they began to relate this knowledge to their fellow man. At the beginning this knowledge may have been transmitted as a simple sound or gesture: a cry of warning or an eager nod of the head. But as time went on, humans began to string together these sounds and bits of knowledge into words, and then into story, and sometimes into song. -

Federal Bureau of Investigation Department of Homeland Security

Federal Bureau of Investigation Department of Homeland Security Strategic Intelligence Assessment and Data on Domestic Terrorism Submitted to the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, the Committee on Homeland Security, and the Committee of the Judiciary of the United States House of Representatives, and the Select Committee on Intelligence, the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, and the Committee of the Judiciary of the United States Senate May 2021 Page 1 of 40 Table of Contents I. Overview of Reporting Requirement ............................................................................................. 2 II. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 III. Introduction...................................................................................................................................... 2 IV. Strategic Intelligence Assessment ................................................................................................... 5 V. Discussion and Comparison of Investigative Activities ................................................................ 9 VI. FBI Data on Domestic Terrorism ................................................................................................. 19 VII. Recommendations .......................................................................................................................... 27 Appendix .................................................................................................................................................... -

Civil Defense and Homeland Security: a Short History of National Preparedness Efforts

Civil Defense and Homeland Security: A Short History of National Preparedness Efforts September 2006 Homeland Security National Preparedness Task Force 1 Civil Defense and Homeland Security: A Short History of National Preparedness Efforts September 2006 Homeland Security National Preparedness Task Force 2 ABOUT THIS REPORT This report is the result of a requirement by the Director of the Department of Homeland Security’s National Preparedness Task Force to examine the history of national preparedness efforts in the United States. The report provides a concise and accessible historical overview of U.S. national preparedness efforts since World War I, identifying and analyzing key policy efforts, drivers of change, and lessons learned. While the report provides much critical information, it is not meant to be a substitute for more comprehensive historical and analytical treatments. It is hoped that the report will be an informative and useful resource for policymakers, those individuals interested in the history of what is today known as homeland security, and homeland security stakeholders responsible for the development and implementation of effective national preparedness policies and programs. 3 Introduction the Nation’s diverse communities, be carefully planned, capable of quickly providing From the air raid warning and plane spotting pertinent information to the populace about activities of the Office of Civil Defense in the imminent threats, and able to convey risk 1940s, to the Duck and Cover film strips and without creating unnecessary alarm. backyard shelters of the 1950s, to today’s all- hazards preparedness programs led by the The following narrative identifies some of the Department of Homeland Security, Federal key trends, drivers of change, and lessons strategies to enhance the nation’s learned in the history of U.S. -

US Responses to Self-Determination Movements

U.S. RESPONSES TO SELF-DETERMINATION MOVEMENTS Strategies for Nonviolent Outcomes and Alternatives to Secession Report from a Roundtable Held in Conjunction with the Policy Planning Staff of the U.S. Department of State Patricia Carley UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE CONTENTS Key Points v Preface viii 1 Introduction 1 2 Self-Determination: Four Case Studies 3 3 Self-Determination, Human Rights, and Good Governance 14 4 A Case for Secession 17 5 Self-Determination at the United Nations 21 6 Nonviolent Alternatives to Secession: U.S. Policy Options 23 7 Conclusion 28 About the Author 29 About the Institute 30 v refugees from Iraq into Turkey heightened world awareness of the Kurdish issue in general and highlighted Kurdish distinctiveness. The forma- tion in the 1970s in Turkey of the Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, a radical and violent Marxist-Leninist organization, also intensified the issue; the PKK’s success in rallying the Kurds’ sense of identity cannot be denied. Though the KEY POINTS PKK has retreated from its original demand for in- dependence, the Turks fear that any concession to their Kurdish population will inevitably lead to an end to the Turkish state. - Although the Kashmir issue involves both India’s domestic politics and its relations with neighbor- ing Pakistan, the immediate problem is the insur- rection in Kashmir itself. Kashmir’s inclusion in the state of India carried with it provisions for considerable autonomy, but the Indian govern- ment over the decades has undermined that au- tonomy, a process eventually resulting in - Though the right to self-determination is included anti-Indian violence in Kashmir in the late 1980s. -

Maya Medicine*

MAYA MEDICINE* by FRANCISCO GUERRA THE traditional dependence of the European historian on cultural patterns developed by Mediterranean civilizations tends to disregard pre-Columbian achievements in the New World. Our main cultural stream had its source around the 3rd millennium B.C. in the Nile, Euphrates and Indus valleys, when the oldest civilizations developed an agriculture based on artificial irrigation. Egyptians and Hindus worked metals, used beasts of burden and the plough, and established a system of writing; the Sumerians added to all these technical achievements the principle of the wheel. New World Civilizations In that far-off age the American Indians were still migrating southwards and establishing themselves in territories where domestication of maize became possible. To the three great American civilizations-Maya, Aztec and Inca- the wheel, the plough, iron implements, and the use of beasts of burden remained unknown until the arrival of the Europeans, although the Inca made limited use of the llama. A true system of writing going beyond pictographic representation was attained only by the Maya, but the Aztec reached the greatest military and political power without any such advances. Despite these technical limitations the pre-Columbian Americans could claim in a few instances some intellectual superiority over the Old World. The Maya possessed a philosophical outlook on life, a sense of balance, of architectural perfection and an unquestioned mathematical accomplishment which made them, so to speak, the Greeks of the New World. In the same way, the political enterprises of the Aztecs may be compared with those of the Romans; and carrying the simile a step farther we could find a parallel of agressiveness between Incas and Carthaginians. -

Download My Fact Sheet

Institute for a College of Humanities Sustainable Earth and Social Sciences Christopher Morris, PhD Assistant Professor, Sociology and Anthropology Education PhD, Anthropology, University of Colorado at Boulder Key Interests Environmental Governance | Extractive Economies | Biological and Genetic Resources | Pharmaceutical Politics | Indigeneity | Ethnicity | Property | Colonialism and Postcolonialism | Land Rights | Southern Africa CONTACT Phone: 720-988-8763 | Email: [email protected] Website: https://gmu.academia.edu/ChristopherMorris SELECT PUBLICATIONS Research Focus › Morris, C. (2016). Royal My recent work particularly examines the environmental, indigenous, and spatial politics of pharmaceuticals: contestation over biological resources in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. The resources Bioprospecting, rights, and are removed and marketed around the world as medicines by multinational companies. My book traditional authority in South manuscript on this subject highlights the complex relationship between the global governance of Africa. American Ethnologist, biodiversity conservation and commercialization, explosions in indigenous rights consciousness, 43(3), 525–539. and the role of foreign firms in local politics. In another recently completed study, I used › Morris, C. (2019). A interviews with medical doctors and researchers to examine a unique clinical trial in South Africa ‘Homeland’s’ harvest: Biotraffic that assessed the safety and efficacy of an African traditional medicine in HIV-seropositive and biotrade in the persons. contemporary Ciskei region of South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 45(3), 597–616. › Morris, C. (2017). Biopolitics and boundary work in South Africa’s sutherlandia clinical trial. Medical Anthropology, 36(7), 685–698. › Morris, C. (2013). Pharmaceutical Bioprospecting and the law: The case of umckaloabo in a former apartheid homeland of South Africa. -

Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México

Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México By Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Stanley Brandes, Chair Professor William F. Hanks Professor Lawrence Cohen Professor William B. Taylor Spring 2011 Adoring our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México Copyright 2011 by Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes Abstract Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México By Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Stanley S. Brandes The first decade of the 21st century has seen a transformation in national and regional Mexican politics and society. In the state of Yucatán, this transformation has taken the shape of a newfound interest in indigenous Maya culture coupled with increasing involvement by the state in public health efforts. Suicide, which in Yucatán more than doubles the national average, has captured the attention of local newspaper media, public health authorities, and the general public; it has become a symbol of indigenous Maya culture due to an often cited association with Ixtab, an ancient Maya ―suicide goddess‖. My thesis investigates suicide as a socially produced cultural artifact. It is a study of how suicide is understood by many social actors and institutions and of how upon a close examination, suicide can be seen as a trope that illuminates the complexity of class, ethnicity, and inequality in Yucatán. In particular, my dissertation –based on extensive ethnographic and archival research in Valladolid and Mérida, Yucatán, México— is a study of both suicide and suicide prevention efforts. -

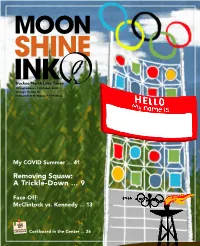

Removing Squaw: a Trickle-Down

Truckee/North Lake Tahoe 10 September – 7 October 2020 Vintage 18, Nip 10 Independent Newspaper • Priceless My COVID Summer ... 41 Removing Squaw: A Trickle-Down ... 9 Face-Off: McClintock vs. Kennedy ... 13 Community Corkboard Corkboard in the Center ... 26 WANT TO EARN STABLE MONTHLY INCOME FROM YOUR VACATION HOME? With the instability in short-term rentals because of COVID-19, have you been thinking about renting longer-term? Our team handles everything needed to find a vetted, locally-employed tenant so you can earn guaranteed monthly income. LandingLocals.com (530)213-3093 CA DRE #02103731 Green Initiatives Over the past fi ve years, we’ve developed a number of initiatives that reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and keep our community clean and blue. New fl ight tracking program (ADS-B) allows for GOING GREEN TO KEEP more e cient fl ying Implementation of Greenhouse Gas Inventory & GHG OUR REGION BLUE. Emission Reduction Plan Land management plan for forest We live in a special place. As a deeply committed community partner, health and wildfi re prevention the Truckee Tahoe Airport District cares about our environment and Open-space land acquisitions for we work diligently to minimize the airport’s impact on the region. From public use new ADS-B technology, to using electric vehicles on the airfi eld, and Electric vehicles & E-bikes used on fi eld preserving more than 1,600 acres of open space land, the District will continue to seek the most sustainable way of operating. Photo by Anders Clark, Disciples of Flight Energy-e cient hangar