An Analysis of Palestinian and Native American Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voyeurisme, Intimitet Og Paranoia I Tv-Serien Homeland

Politik Nummer 1 | Årgang 20 | 2017 Drone-dronningen: Voyeurisme, intimitet og paranoia i tv-serien Homeland Andreas Immanuel Graae, Ph.d.-stipendiat, Litteraturvidenskab, Syddansk Universitet Kamikazepiloten: Min krop er et våben. Dronen: Mit våben har ingen krop.” - Chamayou 2015, 84 I hovedværket A Theory of the Drone (2015) trækker den franske filosof Grégoire Chamayou linjerne hårdt op mellem to typer krigere: Selvmordsbomberen og dronepiloten. Hvor selvmordsbomberen, herunder kamikazepiloten, med sin handling foretager den ultimative ofring af egen krop, markerer dronepiloten omvendt et totalt fravær af krop i kampzonen; de repræsenterer to politiske og affektive logikker, der ofte modstilles i den akademiske dronedebat såvel som i populærkulturelle repræsentationer af dronekrig.1 Opfattelsen af dronekrig som en grundlæggende kropsløs og virtuel affære understøttes af udbredte forestillinger og fordomme om droneoperationer som ren simulation eller ligefrem et computerspil, der producerer en ’PlayStation-mentalitet’ blandt piloterne (Chamayou 2015, 107; Gregory 2014, 9). Der skal ikke herske tvivl om, at de senere årtiers teknologiske fremskridt har øget militærindustriens interesse for simulationer, computergenerede modeller, netværk og algoritmer (Derian 2009). Men selvom skærmkrigerens manglende kropslige involvering i begivenhederne på slagmarken kan stilles op over for selvmordsbomberens ultimative kropslige offer, betyder det ikke nødvendigvis, at følelsesmæssig indlevelse og erfaring er totalt fraværende i dronekrig. Tværtimod tyder talrige rapporter om psykiske nedbrud og PTSD-diagnoser blandt dronepiloterne på væsentlig mental fordybelse og emotionel indlevelsesevne (Chamayou 2015, 106). 1 For eksempel tegner poprock-gruppen Muse i albummet Drones (2015) et dehumaniseret billede af dronekrig, hvor der er ”no recourse, and there is no one behind the wheel,” som det hedder på tracket ‘Reapers.’ 62 Politik Nummer 1 | Årgang 20 | 2017 Adskillige nyere film og tv-serier adresserer denne problematik i deres repræsentationer af dronekrig. -

Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College English Honors Projects English Department 2012 Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgerald, Amy, "Threnody" (2012). English Honors Projects. Paper 21. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors/21 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Threnody By Amy Fitzgerald English Department Honors Project, May 2012 Advisor: Peter Bognanni 1 Glossary of Words, Terms, and Institutions Commissie voor Oorlogspleegkinderen : Commission for War Foster Children; formed after World War II to relocate war orphans in the Netherlands, most of whom were Jewish (Dutch) Crèche : nursery (French origin) Fraulein : Miss (German) Hervormde Kweekschool : Reformed (religion) teacher’s training college Hollandsche Shouwberg : Dutch Theater Huppah : Jewish wedding canopy Kaddish : multipurpose Jewish prayer with several versions, including the Mourners’ Kaddish KP (full name Knokploeg): Assault Group, a Dutch resistance organization LO (full name Landelijke Organasatie voor Hulp aan Onderduikers): National Organization -

Jantzen on Wempe. Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations

H-German Jantzen on Wempe. Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations. Discussion published by Jennifer Wunn on Wednesday, May 26, 2021 Review published on Friday, May 21, 2021 Author: Sean Andrew Wempe Reviewer: Mark Jantzen Jantzen on Wempe, 'Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations' Sean Andrew Wempe. Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. 304 pp. $78.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-19-090721-1. Reviewed by Mark Jantzen (Bethel College)Published on H-Nationalism (May, 2021) Commissioned by Evan C. Rothera (University of Arkansas - Fort Smith) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=56206 Demise or Transmutation for a Unique National Identity? Sean Andrew Wempe’s investigation of the afterlife in the 1920s of the Germans who lived in Germany’s colonies challenges a narrative that sees them primarily as forerunners to Nazi brutality and imperial ambitions. Instead, he follows them down divergent paths that run the gamut from rejecting German citizenship en masse in favor of South African papers in the former German Southwest Africa to embracing the new postwar era’s ostensibly more liberal and humane version of imperialism supervised by the League of Nations to, of course, trying to make their way in or even support Nazi Germany. The resulting well-written, nuanced examination of a unique German national identity, that of colonial Germans, integrates the German colonial experience into Weimar and Nazi history in new and substantive ways. -

Federal Bureau of Investigation Department of Homeland Security

Federal Bureau of Investigation Department of Homeland Security Strategic Intelligence Assessment and Data on Domestic Terrorism Submitted to the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, the Committee on Homeland Security, and the Committee of the Judiciary of the United States House of Representatives, and the Select Committee on Intelligence, the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, and the Committee of the Judiciary of the United States Senate May 2021 Page 1 of 40 Table of Contents I. Overview of Reporting Requirement ............................................................................................. 2 II. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 III. Introduction...................................................................................................................................... 2 IV. Strategic Intelligence Assessment ................................................................................................... 5 V. Discussion and Comparison of Investigative Activities ................................................................ 9 VI. FBI Data on Domestic Terrorism ................................................................................................. 19 VII. Recommendations .......................................................................................................................... 27 Appendix .................................................................................................................................................... -

Civil Defense and Homeland Security: a Short History of National Preparedness Efforts

Civil Defense and Homeland Security: A Short History of National Preparedness Efforts September 2006 Homeland Security National Preparedness Task Force 1 Civil Defense and Homeland Security: A Short History of National Preparedness Efforts September 2006 Homeland Security National Preparedness Task Force 2 ABOUT THIS REPORT This report is the result of a requirement by the Director of the Department of Homeland Security’s National Preparedness Task Force to examine the history of national preparedness efforts in the United States. The report provides a concise and accessible historical overview of U.S. national preparedness efforts since World War I, identifying and analyzing key policy efforts, drivers of change, and lessons learned. While the report provides much critical information, it is not meant to be a substitute for more comprehensive historical and analytical treatments. It is hoped that the report will be an informative and useful resource for policymakers, those individuals interested in the history of what is today known as homeland security, and homeland security stakeholders responsible for the development and implementation of effective national preparedness policies and programs. 3 Introduction the Nation’s diverse communities, be carefully planned, capable of quickly providing From the air raid warning and plane spotting pertinent information to the populace about activities of the Office of Civil Defense in the imminent threats, and able to convey risk 1940s, to the Duck and Cover film strips and without creating unnecessary alarm. backyard shelters of the 1950s, to today’s all- hazards preparedness programs led by the The following narrative identifies some of the Department of Homeland Security, Federal key trends, drivers of change, and lessons strategies to enhance the nation’s learned in the history of U.S. -

US Responses to Self-Determination Movements

U.S. RESPONSES TO SELF-DETERMINATION MOVEMENTS Strategies for Nonviolent Outcomes and Alternatives to Secession Report from a Roundtable Held in Conjunction with the Policy Planning Staff of the U.S. Department of State Patricia Carley UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE CONTENTS Key Points v Preface viii 1 Introduction 1 2 Self-Determination: Four Case Studies 3 3 Self-Determination, Human Rights, and Good Governance 14 4 A Case for Secession 17 5 Self-Determination at the United Nations 21 6 Nonviolent Alternatives to Secession: U.S. Policy Options 23 7 Conclusion 28 About the Author 29 About the Institute 30 v refugees from Iraq into Turkey heightened world awareness of the Kurdish issue in general and highlighted Kurdish distinctiveness. The forma- tion in the 1970s in Turkey of the Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, a radical and violent Marxist-Leninist organization, also intensified the issue; the PKK’s success in rallying the Kurds’ sense of identity cannot be denied. Though the KEY POINTS PKK has retreated from its original demand for in- dependence, the Turks fear that any concession to their Kurdish population will inevitably lead to an end to the Turkish state. - Although the Kashmir issue involves both India’s domestic politics and its relations with neighbor- ing Pakistan, the immediate problem is the insur- rection in Kashmir itself. Kashmir’s inclusion in the state of India carried with it provisions for considerable autonomy, but the Indian govern- ment over the decades has undermined that au- tonomy, a process eventually resulting in - Though the right to self-determination is included anti-Indian violence in Kashmir in the late 1980s. -

As She Knows It

BY VICKI GLEMBOCKI ’93, ’02 MFA LIB THE END OF THE WORLD as she knows it When it comes to surviving a zombie apocalypse, GILLIAN ALBINSKI knows firsthand what to eat, how to make weapons, what to do with undead blood, and how to make anything out of tinfoil. They’re useful skills—both for staying alive at the end of days, and for being the prop master on one of the most-watched shows on TV, The Walking Dead. TK TK PENNPENN STATER STATER MAGAZINE MAGAZINE 47 THE END OF THE WORLD STARSTRUCK A fan of TWD since it debuted in 2010, Albinski says she arrived on set last August and “I suddenly got all giggly fan-girl.” mist, in real time, dressing a deer that a client had brought in. And there was IT WAS CLOSE TO MIDNIGHT lots of blood. Albinski, 48, jumped up, tossed her when Gillian Albinski pulled down the deserted, supplies in her van, and headed to the shop, an hour-and-a-half drive from tree-lined road that led to Senoia, a small town just Senoia where TWD is filmed, praying she’d get there before the blood coag- south of Atlanta. In the back of her minivan, she ulated. She figured she’d set up her experiment in the parking lot: pour the had several two-by-fours, a butane lighter, a bucket, blood in the bucket, dip in the wood, light it on fire, repeat and repeat and and a sealed Rubbermaid pitcher filled with deer blood. wrapped in barbed wire that’s the weapon of choice of repeat, and take tons of photos. -

Download My Fact Sheet

Institute for a College of Humanities Sustainable Earth and Social Sciences Christopher Morris, PhD Assistant Professor, Sociology and Anthropology Education PhD, Anthropology, University of Colorado at Boulder Key Interests Environmental Governance | Extractive Economies | Biological and Genetic Resources | Pharmaceutical Politics | Indigeneity | Ethnicity | Property | Colonialism and Postcolonialism | Land Rights | Southern Africa CONTACT Phone: 720-988-8763 | Email: [email protected] Website: https://gmu.academia.edu/ChristopherMorris SELECT PUBLICATIONS Research Focus › Morris, C. (2016). Royal My recent work particularly examines the environmental, indigenous, and spatial politics of pharmaceuticals: contestation over biological resources in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. The resources Bioprospecting, rights, and are removed and marketed around the world as medicines by multinational companies. My book traditional authority in South manuscript on this subject highlights the complex relationship between the global governance of Africa. American Ethnologist, biodiversity conservation and commercialization, explosions in indigenous rights consciousness, 43(3), 525–539. and the role of foreign firms in local politics. In another recently completed study, I used › Morris, C. (2019). A interviews with medical doctors and researchers to examine a unique clinical trial in South Africa ‘Homeland’s’ harvest: Biotraffic that assessed the safety and efficacy of an African traditional medicine in HIV-seropositive and biotrade in the persons. contemporary Ciskei region of South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 45(3), 597–616. › Morris, C. (2017). Biopolitics and boundary work in South Africa’s sutherlandia clinical trial. Medical Anthropology, 36(7), 685–698. › Morris, C. (2013). Pharmaceutical Bioprospecting and the law: The case of umckaloabo in a former apartheid homeland of South Africa. -

A Governor's Guide to Homeland Security

A GOVERNOR’S GUIDE TO HOMELAND SECURITY THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION (NGA), founded in 1908, is the instrument through which the nation’s governors collectively influence the development and implementation of national policy and apply creative leadership to state issues. Its members are the governors of the 50 states, three territories and two commonwealths. The NGA Center for Best Practices is the nation’s only dedicated consulting firm for governors and their key policy staff. The NGA Center’s mission is to develop and implement innovative solutions to public policy challenges. Through the staff of the NGA Center, governors and their policy advisors can: • Quickly learn about what works, what doesn’t and what lessons can be learned from other governors grappling with the same problems; • Obtain specialized assistance in designing and implementing new programs or improving the effectiveness of current programs; • Receive up-to-date, comprehensive information about what is happening in other state capitals and in Washington, D.C., so governors are aware of cutting-edge policies; and • Learn about emerging national trends and their implications for states, so governors can prepare to meet future demands. For more information about NGA and the Center for Best Practices, please visit www.nga.org. A GOVERNOR’S GUIDE TO HOMELAND SECURITY NGA Center for Best Practices Homeland Security & Public Safety Division FEBRUARY 2019 Acknowledgements A Governor’s Guide to Homeland Security was produced by the Homeland Security & Public Safety Division of the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) including Maggie Brunner, Reza Zomorrodian, David Forscey, Michael Garcia, Mary Catherine Ott, and Jeff McLeod. -

Removing Squaw: a Trickle-Down

Truckee/North Lake Tahoe 10 September – 7 October 2020 Vintage 18, Nip 10 Independent Newspaper • Priceless My COVID Summer ... 41 Removing Squaw: A Trickle-Down ... 9 Face-Off: McClintock vs. Kennedy ... 13 Community Corkboard Corkboard in the Center ... 26 WANT TO EARN STABLE MONTHLY INCOME FROM YOUR VACATION HOME? With the instability in short-term rentals because of COVID-19, have you been thinking about renting longer-term? Our team handles everything needed to find a vetted, locally-employed tenant so you can earn guaranteed monthly income. LandingLocals.com (530)213-3093 CA DRE #02103731 Green Initiatives Over the past fi ve years, we’ve developed a number of initiatives that reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and keep our community clean and blue. New fl ight tracking program (ADS-B) allows for GOING GREEN TO KEEP more e cient fl ying Implementation of Greenhouse Gas Inventory & GHG OUR REGION BLUE. Emission Reduction Plan Land management plan for forest We live in a special place. As a deeply committed community partner, health and wildfi re prevention the Truckee Tahoe Airport District cares about our environment and Open-space land acquisitions for we work diligently to minimize the airport’s impact on the region. From public use new ADS-B technology, to using electric vehicles on the airfi eld, and Electric vehicles & E-bikes used on fi eld preserving more than 1,600 acres of open space land, the District will continue to seek the most sustainable way of operating. Photo by Anders Clark, Disciples of Flight Energy-e cient hangar -

Ilan Pappé Zionism As Colonialism

Ilan Pappé Zionism as Colonialism: A Comparative View of Diluted Colonialism in Asia and Africa Introduction: The Reputation of Colonialism Ever since historiography was professionalized as a scientific discipline, historians have consid- ered the motives for mass human geographical relocations. In the twentieth century, this quest focused on the colonialist settler projects that moved hundreds of thousands of people from Europe into America, Asia, and Africa in the pre- ceding centuries. The various explanations for this human transit have changed considerably in recent times, and this transformation is the departure point for this essay. The early explanations for human relocations were empiricist and positivist; they assumed that every human action has a concrete explanation best found in the evidence left by those who per- formed the action. The practitioners of social his- tory were particularly interested in the question, and when their field of inquiry was impacted by trends in philosophy and linguistics, their conclusion differed from that of the previous generation. The research on Zionism should be seen in light of these historiographical developments. Until recently, in the Israeli historiography, the South Atlantic Quarterly 107:4, Fall 2008 doi 10.1215/00382876-2008-009 © 2008 Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/south-atlantic-quarterly/article-pdf/107/4/611/470173/SAQ107-04-01PappeFpp.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 612 Ilan Pappé dominant explanation for the movement of Jews from Europe to Palestine in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was—and, in many ways, still is—positivist and empiricist.1 Researchers analyzed the motives of the first group of settlers who arrived on Palestine’s shores in 1882 according to the testimonies in their diaries and other documents. -

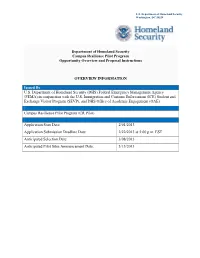

CR Pilot Program Announcement

U.S. Department of Homeland Security Washington, DC 20528 Department of Homeland Security Campus Resilience Pilot Program Opportunity Overview and Proposal Instructions OVERVIEW INFORMATION Issued By U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in conjunction with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP), and DHS Office of Academic Engagement (OAE). Opportunity Announcement Title Campus Resilience Pilot Program (CR Pilot) Key Dates and Time Application Start Date: 2/01/2013 Application Submission Deadline Date: 2/22/2013 at 5:00 p.m. EST Anticipated Selection Date: 3/08/2013 Anticipated Pilot Sites Announcement Date: 3/15/2013 DHS CAMPUS RESILIENCE PILOT PROGRAM PROPOSAL SUBMISSION PROCESS & ELIGIBILITY Opportunity Category Select the applicable opportunity category: Discretionary Mandatory Competitive Non-competitive Sole Source (Requires Awarding Office Pre-Approval and Explanation) CR Pilot sites will be selected based on evaluation criteria described in Section V. Proposal Submission Process Completed proposals should be emailed to [email protected] by 5:00 p.m. EST on Friday, February 22, 2013. Only electronic submissions will be accepted. Please reference “Campus Resilience Pilot Program” in the subject line. The file size limit is 5MB. Please submit in Adobe Acrobat or Microsoft Word formats. An email acknowledgement of received submission will be sent upon receipt. Eligible Applicants The following entities are eligible to apply for participation in the CR Pilot: • Not-for-profit accredited public and state controlled institutions of higher education • Not-for-profit accredited private institutions of higher education Additional information should be provided under Full Announcement, Section III, Eligibility Criteria.