National Incident Management System (NIMS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voyeurisme, Intimitet Og Paranoia I Tv-Serien Homeland

Politik Nummer 1 | Årgang 20 | 2017 Drone-dronningen: Voyeurisme, intimitet og paranoia i tv-serien Homeland Andreas Immanuel Graae, Ph.d.-stipendiat, Litteraturvidenskab, Syddansk Universitet Kamikazepiloten: Min krop er et våben. Dronen: Mit våben har ingen krop.” - Chamayou 2015, 84 I hovedværket A Theory of the Drone (2015) trækker den franske filosof Grégoire Chamayou linjerne hårdt op mellem to typer krigere: Selvmordsbomberen og dronepiloten. Hvor selvmordsbomberen, herunder kamikazepiloten, med sin handling foretager den ultimative ofring af egen krop, markerer dronepiloten omvendt et totalt fravær af krop i kampzonen; de repræsenterer to politiske og affektive logikker, der ofte modstilles i den akademiske dronedebat såvel som i populærkulturelle repræsentationer af dronekrig.1 Opfattelsen af dronekrig som en grundlæggende kropsløs og virtuel affære understøttes af udbredte forestillinger og fordomme om droneoperationer som ren simulation eller ligefrem et computerspil, der producerer en ’PlayStation-mentalitet’ blandt piloterne (Chamayou 2015, 107; Gregory 2014, 9). Der skal ikke herske tvivl om, at de senere årtiers teknologiske fremskridt har øget militærindustriens interesse for simulationer, computergenerede modeller, netværk og algoritmer (Derian 2009). Men selvom skærmkrigerens manglende kropslige involvering i begivenhederne på slagmarken kan stilles op over for selvmordsbomberens ultimative kropslige offer, betyder det ikke nødvendigvis, at følelsesmæssig indlevelse og erfaring er totalt fraværende i dronekrig. Tværtimod tyder talrige rapporter om psykiske nedbrud og PTSD-diagnoser blandt dronepiloterne på væsentlig mental fordybelse og emotionel indlevelsesevne (Chamayou 2015, 106). 1 For eksempel tegner poprock-gruppen Muse i albummet Drones (2015) et dehumaniseret billede af dronekrig, hvor der er ”no recourse, and there is no one behind the wheel,” som det hedder på tracket ‘Reapers.’ 62 Politik Nummer 1 | Årgang 20 | 2017 Adskillige nyere film og tv-serier adresserer denne problematik i deres repræsentationer af dronekrig. -

Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College English Honors Projects English Department 2012 Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgerald, Amy, "Threnody" (2012). English Honors Projects. Paper 21. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors/21 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Threnody By Amy Fitzgerald English Department Honors Project, May 2012 Advisor: Peter Bognanni 1 Glossary of Words, Terms, and Institutions Commissie voor Oorlogspleegkinderen : Commission for War Foster Children; formed after World War II to relocate war orphans in the Netherlands, most of whom were Jewish (Dutch) Crèche : nursery (French origin) Fraulein : Miss (German) Hervormde Kweekschool : Reformed (religion) teacher’s training college Hollandsche Shouwberg : Dutch Theater Huppah : Jewish wedding canopy Kaddish : multipurpose Jewish prayer with several versions, including the Mourners’ Kaddish KP (full name Knokploeg): Assault Group, a Dutch resistance organization LO (full name Landelijke Organasatie voor Hulp aan Onderduikers): National Organization -

National Strategy for Homeland Security 2007

national strategy for HOMELAND SECURITY H OMELAND SECURITY COUNCIL OCTOBER 2 0 0 7 national strategy for HOMELAND SECURITY H OMELAND SECURITY COUNCIL OCTOBER 2 0 0 7 My fellow Americans, More than 6 years after the attacks of September 11, 2001, we remain at war with adversar- ies who are committed to destroying our people, our freedom, and our way of life. In the midst of this conflict, our Nation also has endured one of the worst natural disasters in our history, Hurricane Katrina. As we face the dual challenges of preventing terrorist attacks in the Homeland and strengthening our Nation’s preparedness for both natural and man-made disasters, our most solemn duty is to protect the American people. The National Strategy for Homeland Security serves as our guide to leverage America’s talents and resources to meet this obligation. Despite grave challenges, we also have seen great accomplishments. Working with our part- ners and allies, we have broken up terrorist cells, disrupted attacks, and saved American lives. Although our enemies have not been idle, they have not succeeded in launching another attack on our soil in over 6 years due to the bravery and diligence of many. Just as our vision of homeland security has evolved as we have made progress in the War on Terror, we also have learned from the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina. We witnessed countless acts of courage and kindness in the aftermath of that storm, but I, like most Americans, was not satisfied with the Federal response. We have applied the lessons of Katrina to thisStrategy to make sure that America is safer, stronger, and better prepared. -

An Analysis of Palestinian and Native American Literature

INDIGENOUS CONTINUANCE THROUGH HOMELAND: AN ANALYSIS OF PALESTINIAN AND NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE ________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University ________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English ________________________________________ by Alana E. Dakin June 2012 Dakin 2 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of English ____________________ Dr. George Hartley Professor, English Thesis Advisor ____________________ Dr. Carey Snyder Honors Tutorial College, Director of Studies English ____________________ Dr. Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College Dakin 3 CHAPTER ONE Land is more than just the ground on which we stand. Land is what provides us with the plants and animals that give us sustenance, the resources to build our shelters, and a place to rest our heads at night. It is the source of the most sublime beauty and the most complete destruction. Land is more than just dirt and rock; it is a part of the cycle of life and death that is at the very core of the cultures and beliefs of human civilizations across the centuries. As human beings began to navigate the surface of the earth thousands of years ago they learned the nuances of the land and the creatures that inhabited it, and they began to relate this knowledge to their fellow man. At the beginning this knowledge may have been transmitted as a simple sound or gesture: a cry of warning or an eager nod of the head. But as time went on, humans began to string together these sounds and bits of knowledge into words, and then into story, and sometimes into song. -

Civil Defense and Homeland Security: a Short History of National Preparedness Efforts

Civil Defense and Homeland Security: A Short History of National Preparedness Efforts September 2006 Homeland Security National Preparedness Task Force 1 Civil Defense and Homeland Security: A Short History of National Preparedness Efforts September 2006 Homeland Security National Preparedness Task Force 2 ABOUT THIS REPORT This report is the result of a requirement by the Director of the Department of Homeland Security’s National Preparedness Task Force to examine the history of national preparedness efforts in the United States. The report provides a concise and accessible historical overview of U.S. national preparedness efforts since World War I, identifying and analyzing key policy efforts, drivers of change, and lessons learned. While the report provides much critical information, it is not meant to be a substitute for more comprehensive historical and analytical treatments. It is hoped that the report will be an informative and useful resource for policymakers, those individuals interested in the history of what is today known as homeland security, and homeland security stakeholders responsible for the development and implementation of effective national preparedness policies and programs. 3 Introduction the Nation’s diverse communities, be carefully planned, capable of quickly providing From the air raid warning and plane spotting pertinent information to the populace about activities of the Office of Civil Defense in the imminent threats, and able to convey risk 1940s, to the Duck and Cover film strips and without creating unnecessary alarm. backyard shelters of the 1950s, to today’s all- hazards preparedness programs led by the The following narrative identifies some of the Department of Homeland Security, Federal key trends, drivers of change, and lessons strategies to enhance the nation’s learned in the history of U.S. -

9110-9P Department of Homeland Security

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 06/23/2021 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2021-13109, and on govinfo.gov 9110-9P DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY [Docket No. CISA-2020-0018] Agency Information Collection Activities: Proposed Collection; Comment Request; Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Visitor Request Form AGENCY: Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), Department of Homeland Security (DHS). ACTION: 30-day notice and request for comments; reinstatement without change of information collection request: 1670-0036. SUMMARY: The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), Office of Compliance and Security (OCS), as part of its continuing effort to reduce paperwork and respondent burden, invites the general public to take this opportunity to comment on a reinstatement, without change, of a previously approved information collection for which approval has expired. CISA will submit the following Information Collection Request to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for review and clearance in accordance with the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995. CISA previously published a notice about this ICR, in the Federal Register on February 17, 2021, for a 60-day public comment period. There were no comments received. The purpose of this notice is to allow additional 30-days for public comments. DATES: The comment period for the information collection request published on February 17, 2021 at 86 FR 9949. Comments must be submitted on or before [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. ADDRESSES: Written comments and recommendations for the proposed information collection should be sent within 30 days of publication of this notice to www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAMain . -

As She Knows It

BY VICKI GLEMBOCKI ’93, ’02 MFA LIB THE END OF THE WORLD as she knows it When it comes to surviving a zombie apocalypse, GILLIAN ALBINSKI knows firsthand what to eat, how to make weapons, what to do with undead blood, and how to make anything out of tinfoil. They’re useful skills—both for staying alive at the end of days, and for being the prop master on one of the most-watched shows on TV, The Walking Dead. TK TK PENNPENN STATER STATER MAGAZINE MAGAZINE 47 THE END OF THE WORLD STARSTRUCK A fan of TWD since it debuted in 2010, Albinski says she arrived on set last August and “I suddenly got all giggly fan-girl.” mist, in real time, dressing a deer that a client had brought in. And there was IT WAS CLOSE TO MIDNIGHT lots of blood. Albinski, 48, jumped up, tossed her when Gillian Albinski pulled down the deserted, supplies in her van, and headed to the shop, an hour-and-a-half drive from tree-lined road that led to Senoia, a small town just Senoia where TWD is filmed, praying she’d get there before the blood coag- south of Atlanta. In the back of her minivan, she ulated. She figured she’d set up her experiment in the parking lot: pour the had several two-by-fours, a butane lighter, a bucket, blood in the bucket, dip in the wood, light it on fire, repeat and repeat and and a sealed Rubbermaid pitcher filled with deer blood. wrapped in barbed wire that’s the weapon of choice of repeat, and take tons of photos. -

Pointing Towards Clarity Or Missing the Point? a Critique of the Proposed "Social Group" Rule and Its Impact on Gender-Based Political Asylum

POINTING TOWARDS CLARITY OR MISSING THE POINT? A CRITIQUE OF THE PROPOSED "SOCIAL GROUP" RULE AND ITS IMPACT ON GENDER-BASED POLITICAL ASYLUM LOREN G. STEWART* From the beginning of the marriage, her husband abused her. He raped her almost daily, beating her before and during each rape. He once dislocated her jawbone because her menstrual period was fifteen days late. When she refused to abort a pregnancy, he kicked her violently in her spine. Once, he kicked her in her genitalia, causing her severe pain and eight days of bleeding. She fled the city with their children, but he tracked them down and beat her unconscious. He broke windows and mirrors with her head. He told her that if she left him, he would find her, cut off her arms and legs with a machete and leave her in a wheelchair. She attempted suicide, but was unsuccessful. She contacted the police three times, but they did not respond. A judge denied her protection, saying that the court "would not interfere in domestic disputes."' She finally left him, fled to the United States, and applied for political asylum. Should women like Rodi Alvarado Pefia, described above, be eligible to receive political asylum in the United States?2 To be J.D. Candidate 2005, University of Pennsylvania Law School. B.A. History, cum laude, Yale University 1999. The author wishes to express his gratitude to Professors Fernando Chang-Muy, Louis S. Rulli and Catherine Struve for their guidance, enthusiasm, and inspiration. ratience,In re R-A-, 22 I. & N. Dec. 906, 908-10 (BIA 1999, Att'y Gen. -

A Governor's Guide to Homeland Security

A GOVERNOR’S GUIDE TO HOMELAND SECURITY THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION (NGA), founded in 1908, is the instrument through which the nation’s governors collectively influence the development and implementation of national policy and apply creative leadership to state issues. Its members are the governors of the 50 states, three territories and two commonwealths. The NGA Center for Best Practices is the nation’s only dedicated consulting firm for governors and their key policy staff. The NGA Center’s mission is to develop and implement innovative solutions to public policy challenges. Through the staff of the NGA Center, governors and their policy advisors can: • Quickly learn about what works, what doesn’t and what lessons can be learned from other governors grappling with the same problems; • Obtain specialized assistance in designing and implementing new programs or improving the effectiveness of current programs; • Receive up-to-date, comprehensive information about what is happening in other state capitals and in Washington, D.C., so governors are aware of cutting-edge policies; and • Learn about emerging national trends and their implications for states, so governors can prepare to meet future demands. For more information about NGA and the Center for Best Practices, please visit www.nga.org. A GOVERNOR’S GUIDE TO HOMELAND SECURITY NGA Center for Best Practices Homeland Security & Public Safety Division FEBRUARY 2019 Acknowledgements A Governor’s Guide to Homeland Security was produced by the Homeland Security & Public Safety Division of the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) including Maggie Brunner, Reza Zomorrodian, David Forscey, Michael Garcia, Mary Catherine Ott, and Jeff McLeod. -

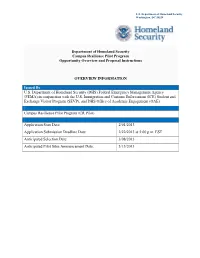

CR Pilot Program Announcement

U.S. Department of Homeland Security Washington, DC 20528 Department of Homeland Security Campus Resilience Pilot Program Opportunity Overview and Proposal Instructions OVERVIEW INFORMATION Issued By U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in conjunction with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP), and DHS Office of Academic Engagement (OAE). Opportunity Announcement Title Campus Resilience Pilot Program (CR Pilot) Key Dates and Time Application Start Date: 2/01/2013 Application Submission Deadline Date: 2/22/2013 at 5:00 p.m. EST Anticipated Selection Date: 3/08/2013 Anticipated Pilot Sites Announcement Date: 3/15/2013 DHS CAMPUS RESILIENCE PILOT PROGRAM PROPOSAL SUBMISSION PROCESS & ELIGIBILITY Opportunity Category Select the applicable opportunity category: Discretionary Mandatory Competitive Non-competitive Sole Source (Requires Awarding Office Pre-Approval and Explanation) CR Pilot sites will be selected based on evaluation criteria described in Section V. Proposal Submission Process Completed proposals should be emailed to [email protected] by 5:00 p.m. EST on Friday, February 22, 2013. Only electronic submissions will be accepted. Please reference “Campus Resilience Pilot Program” in the subject line. The file size limit is 5MB. Please submit in Adobe Acrobat or Microsoft Word formats. An email acknowledgement of received submission will be sent upon receipt. Eligible Applicants The following entities are eligible to apply for participation in the CR Pilot: • Not-for-profit accredited public and state controlled institutions of higher education • Not-for-profit accredited private institutions of higher education Additional information should be provided under Full Announcement, Section III, Eligibility Criteria. -

Texas Homeland Security Strategic Plan 2021-2025

TEXAS HOMELAND SECURITY STRATEGIC PLAN 2021-2025 LETTER FROM THE GOVERNOR Fellow Texans: Over the past five years, we have experienced a wide range of homeland security threats and hazards, from a global pandemic that threatens Texans’ health and economic well-being to the devastation of Hurricane Harvey and other natural disasters to the tragic mass shootings that claimed innocent lives in Sutherland Springs, Santa Fe, El Paso, and Midland-Odessa. We also recall the multi-site bombing campaign in Austin, the cybersecurity attack on over 20 local agencies, a border security crisis that overwhelmed federal capabilities, actual and threatened violence in our cities, and countless other incidents that tested the capabilities of our first responders and the resilience of our communities. In addition, Texas continues to see significant threats from international cartels, gangs, domestic terrorists, and cyber criminals. In this environment, it is essential that we actively assess and manage risks and work together as a team, with state and local governments, the private sector, and individuals, to enhance our preparedness and protect our communities. The Texas Homeland Security Strategic Plan 2021-2025 lays out Texas’ long-term vision to prevent and respond to attacks and disasters. It will serve as a guide in building, sustaining, and employing a wide variety of homeland security capabilities. As we build upon the state’s successes in implementing our homeland security strategy, we must be prepared to make adjustments based on changes in the threat landscape. By fostering a continuous process of learning and improving, we can work together to ensure that Texas is employing the most effective and innovative tactics to keep our communities safe. -

Transnational Ethnic Communities and Rebel Groups' Strategies in a Civil Conflict

Transnational Ethnic Communities and Rebel Groups’ Strategies in a Civil Conflict The case of the Karen National Union rebellion in Myanmar Bethsabée Souris University College London (UCL) 2020 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science I, Bethsabée Souris, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis 1 2 Abstract Few studies have systematically analysed how transnational ethnic kin groups affect the behaviour of domestic ethnic groups in an insurgency, in particular how they have an effect on the types of activities they conduct and their targets. The research question of this study is: What are the mechanisms through which transnational ethnic kin groups influence the domestic rebel ethnic group’s strategies? This thesis analyses the influence of transnational communities on domestic challengers to the state as a two-step process. First, it investigates under which conditions transnational ethnic kin groups provide political and economic support to the rebel ethnic group. It shows that networks between rebel groups and transnational communities, which can enable the diffusion of the rebel group’s conflict frames, are key to ensure transnational support. Second, it examines how such transnational support can influence rebel groups’ strategies. It shows that central to our understanding of rebel groups’ strategies is the cohesion (or lack thereof) of the rebel group. Furthermore, it identifies two sources of rebel group’s fragmentation: the state counter-insurgency strategies, and transnational support. The interaction of these two factors can contribute to the fragmentation of the group and in turn to a shift in the strategies it conducts.