£AZERBAIJAN @Hostages in the Context of the Karabakh Conflict - an Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

Azerbaijan Azerbaijan

COUNTRY REPORT ON THE STATE OF PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE AZERBAIJAN AZERBAIJAN National Report on the State of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture in Azerbaijan Baku – December 2006 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the Second Report on the State of World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The Report is being made available by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as requested by the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 7 INTRODUCTION 8 1. -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Qarabağ Dünən, Bu Gün Və Sabah”

QARABAĞ AZADLIQ TƏŞKİLATI “QARABAĞ DÜNƏN, BU GÜN VƏ SABAH” 18-ci elmi-əməli konfransının MATERİALLARI KONFRANS QARABAĞ GENERAL- QUBERNATORLUĞUNUN 100 İLLİYİNƏ HƏSR OLUNUR BAKI-2019 Redaksiya heyəti: fəlsəfə elmləri doktoru Əli Abasov, tarix elmləri doktoru Qasım Hacıyev, tarix elmləri doktoru Kərim Şükürov, tarix elmləri üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru Firdovsiyyə Əhmədova, iqtisadiyyat üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru Şamil Mehdi. QAT (Qarabağ Azadlıq Təşkilatı). “Qarabağ dünən, bu gün və sabah” 18-ci elmi-əməli konfransının materialları toplusu. Bakı, 2019, səh. 306 Buraxılış Azərbaycan-Ermənistan müharibəsi ilə əlaqədar 2019-cu il mayın 23-də keçirilən “Qarabağ dünən, bu gün və sabah” 18-ci elmi-əməli konfransının məruzə və çıxışlarının materiallarını əhatə edir. This edition covers theses of lectures and speeches o scientific-practical conference “Karabakh yesterday, today and tomorrow”, which was held on May 23, 2019, concerning to settlement of Azerbaijan-Armenia war. Redaksiyadan Bu nəşrdə “Qarabağ dünən, bu gün və sabah” mövzusunda 18-ci elmi-əməli konfransının Ermənistanın Azərbaycana qarşı ərazi iddiaları və onun birbaşa təcavüzü nəticəsində yaranmış Azərbaycan-Ermənistan müharibəsinin müxtəlif cəhətlərinə həsr olunan materialları toplanmışdır. Qarabağ Azadlıq Təşkilatının təşəbbüsü ilə 2019-cu il 23 mayda Bakı şəhərində keçirilən bu konfransın da məqsədi Azərbaycan- Ermənistan münaqişəsinin yaranmasının kökləri və həlli perspektivləri haqqında beynəlxalq ictimaiyyəti məlumatlandırmaqdan, həmçinin taleyüklü problemə dair ədalətli və reallığa uyğun -

The Caucasus Globalization

Volume 8 Issue 3-4 2014 1 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies Volume 8 Issue 3-4 2014 CA&CC Press® SWEDEN 2 Volume 8 Issue 3-4 2014 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION FOUNDED AND PUBLISHED BY INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS Registration number: M-770 Ministry of Justice of Azerbaijan Republic PUBLISHING HOUSE CA&CC Press® Sweden Registration number: 556699-5964 Registration number of the journal: 1218 Editorial Council Eldar Chairman of the Editorial Council (Baku) ISMAILOV Tel/fax: (994 – 12) 497 12 22 E-mail: [email protected] Kenan Executive Secretary (Baku) ALLAHVERDIEV Tel: (994 – 12) 561 70 54 E-mail: [email protected] Azer represents the journal in Russia (Moscow) SAFAROV Tel: (7 – 495) 937 77 27 E-mail: [email protected] Nodar represents the journal in Georgia (Tbilisi) KHADURI Tel: (995 – 32) 99 59 67 E-mail: [email protected] Ayca represents the journal in Turkey (Ankara) ERGUN Tel: (+90 – 312) 210 59 96 E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Nazim Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) MUZAFFARLI Tel: (994 – 12) 598 27 53 (Ext. 25) (IMANOV) E-mail: [email protected] Vladimer Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Georgia) PAPAVA Tel: (995 – 32) 24 35 55 E-mail: [email protected] Akif Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) ABDULLAEV Tel: (994 – 12) 561 70 54 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 8 IssueMembers 3-4 2014 of Editorial Board: 3 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Zaza D.Sc. (History), Professor, Corresponding member of the Georgian National Academy of ALEKSIDZE Sciences, head of the scientific department of the Korneli Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts (Georgia) Mustafa AYDIN Rector of Kadir Has University (Turkey) Irina BABICH D.Sc. -

PROTOCOL No of the SITTING of the ANTI-CORRUPTION

PROTOCOL No OF THE SITTING OF THE ANTI-CORRUPTION COUNCIL HELD ON 17 FEBRUARY 2017, AT 12:00 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- city of Yerevan With the participation of: Members of the Council: K. Karapetyan Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia, Chairperson of the Council V. Gabrielyan Vice Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia, Minister of International Economic Integration and Reforms of the Republic of Armenia D. Harutyunyan Minister-Chief of Staff of the Government of the Republic of Armenia A. Hovhannisyan Minister of Justice of the Republic of Armenia V. Aramyan Minister of Finance of the Republic of Armenia S. Karayan Minister of Economic Development and Investments of the Republic of Armenia A. Tatoyan Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Armenia S. Sahakyan Chairperson of the Commission on Ethics of High-Ranking Officials H. Aslanyan Deputy Prosecutor General of the Republic of Armenia V. Manukyan President of the Public Council of the Republic of Armenia (upon consent) K. Zadoyan Representative of the Anti -Corruption Coalition of Civil Society Organisations of Armenia, "Armenian Lawyers' Association" NGO Invitees: A. Shaboyan Chairp erson of the State Commission for the Protection of Economic Competition of the Republic of Armenia A. Khudaverdyan Deputy Chairperson of the Commission on Ethics of High-Ranking Officials V. Terteryan First Deputy Minister of Territorial Administration and Development of the Republic of Armenia K. Areyan First Deputy Mayor of Yerevan A. Sargsyan Deputy Minister -Chief of Staff of the Government of the Republic of Armenia A. Nazaryan Deputy Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Kh. Hakobyan Deputy Minister of Nature Protection of the Republic of Armenia K. -

Ethnic Profile of Post-Soviet Azerbaijan

Arif Yunusov* Ethnic Profile of Post-Soviet Azerbaijan I. Introduction Following the breakdown of the USSR, interethnic conflicts and rising self-identifica- tion processes in many nations were among the most serious problems that emerged within the territory of the former superpower. Azerbaijan not only failed to avoid these processes but, due to various circumstances, found itself at the forefront of the stand- off. It was in Azerbaijan that the first interethnic conflict in the former USSR started between Armenians and Azeris over Nagorno Karabakh in the late s. This conflict is still unresolved and remains a stumbling block, not only for the relationship between the two Caucasian nations, but also for stability in the entire region. Azerbaijan is a multiethnic country and the progressing ethnic self-identification trends have become a baseline for the emergence of ethnic secessionism within the republic. All these processes have occurred against the background of an independent nation-state construction in Azerbaijan, where the Azeris are the indigenous/titular people. The interethnic conflict with the Armenians over Karabakh, the construction of the nation-state and the upsurge of self-identification movements among the many ethnicities of Azerbaijan are all processes that are occurring simultaneously and sig- nificantly affect other developments unfolding in the republic. How have these proc- esses been developing and what shapes are they going to acquire in the future? What measures have the republican government been applying to solve the minority issues in Azerbaijan? These are the focal issues addressed in this article. II. Ethno-linguistic Situation in Azerbaijan before the Dissolution of the USSR The roots of the current ethnic conflicts and interethnic collisions within the territory of Azerbaijan lie in the distant past when, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Russian empire conquered the South Caucasus and started pursuing a policy of reshaping the region’s existing ethno-confessional profile. -

Download Pdf Brochure

Georgia and Azerbaijan Holidays Get inspired by the contrast of two charming countries situated between the Black and Caspian Seas and surrounded by the stunning Caucasus Mountains. An unforgettable 9-day journey awaits you, as you explore a little-discovered part of the world with two different cultures and religions. From narrow streets of Tbilisi to snow-covered peaks and wonderful vineyards in Georgia, old mosques, caravan routes and modern towers in Azerbaijan, this treasure trove is waiting for you to be discovered. Key information Duration: 9 days / 8 nights Date: All season Tour type: Group of tourists What’s included: Private airport transfers according to your arrival time, Accommodation in 3* hotels for 8 nights, Meals: breakfast, All transfers in air-conditioned/heated cars/buses, English speaking guide service for all days, All admission fees What’s not Included: Flights, Visa fee, Medical insurance, Lunch and dinner Itinerary in brief Day 1 - Arrival Day 2 - Mtskheta - Tbilisi City Tour Day 3 - Ananuri - Gudauri - Gergeti Day 4 - Sighnaghi - Telavi - Tsinandali Day 5 - Georgian-Azerbaijan border - Sheki Day 6 - Gabala City Tour - Baku Day 7 - Baku City Tour Day 8 - Gobustan - Baku - Free time Day 9 - Departure Detailed itinerary Day 1 Arrival at the airport and transfer to the hotel. From this very moment, your acquaintance with Georgia will start. In recent years, more and more tourists from around the world are choosing Georgia as an attractive tourist destination. Its fantastic mountain landscapes, unique culture and mouth-watering national cuisine don't leave anyone indifferent. With the help of our professional guide, you will plunge into the local culture and reveal lots of secrets. -

Agroecological Situation in Wintering Pastures in Azerbaijan,Problems and Solutions (In the Gobustan District)

Global Journal of Otolaryngology ISSN 2474-7556 Review Article Glob J Otolaryngol Volume 13 Issue 1 - January 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by SZ Mammadova DOI: 10.19080/GJO.2018.13.555852 Agroecological Situation in Wintering Pastures in Azerbaijan,Problems and Solutions (In the Gobustan District) SZ Mammadova* Assistant Professor, Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry of ANAS, Azerbaijan Submission: January 04, 2018; Published: January 11, 2017 *Corresponding author: SZ Mammadova, Assistant Professor, Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry of ANAS, Azerbaijan, Email: Abstract forest ecosystems have led to a dramatic decline in the feed base for animal husbandry development. For a well-known purpose in the country of strategicNatural importance, and anthropogenic the assessment impacts of existing of natural natural soil, grassand cultural cover and pasture mainly areas pasture in the (degradation country from areas), their agroeconomic degradation and security desertification perspective, of is a summary of Gobustan analyzes the modern agroecological situation of the pastures, evaluates land and agroechemical grouping and so on. it isusing emphasized scientifically-based that it is important research to in carrythe field out of comprehensive approach and measuresthe use of toeffective improve methods the quality is a problem of the area that in is the relevant affected to areas.agrarian science. Here Keywords : Pasture lands; Pastures, Surface improvement measures; Climatic elements; Agroecological evaluation; Soil erosion; Bonitet; Agro ecological state; Progressive irrigation; Production grouping Introduction in natural resource potential is pasture plowing, large-scale The fact that agriculture has been degraded by important agromeliorative work, excessive livestock grazing and strong degraded lands in the Republic of Azerbaijan, including the man-caused effects. -

Armenian Church of the V

E-NEWSLETTER H - J:RJIK Armenian Church of the V. Revd Dr. Vahan Hovhanessian, Armenian Church of the V . Revd Dr. Vah an Hovhanessian, United Kingdom and Ireland Primate 25th June 2011, Issue 25, Vol 2 ARMENIAN CHURCH FEAST OF HOLY ETCHMIADZIN OF UK & IRELAND This Sunday, 26th June, Armenians around the world will celebrate the THE PRIMATE’S OFFICE Feast of Holy Etchmiadzin, 25 Cheniston Gardens the headquarters of the Kensington universal Armenian Church. London W8 6TG For centuries now, by Tel: 020 8127 8364 celebrating the feast of Fax: 0872 111 5548 Holy Etchmiadzin Armenians celebrate the E-mail: mother Cathedral which primatesoffice@ was built in 303AD, by St. armenianchurch.co.uk Gregory the Illuminator and King Drtad base on a Website: armenianchurch.co.uk vision in which Christ appeared to the saint and Website: instructed him with a The Cathedral of Etchmiadzin Click Here golden hammer to build the Viewed from the Gate of King Drtad cathedral, the first one on earth. The Feast also celebrates the role of Holy Etchmiadzin as the spiritual, GENERAL INFORMATION liturgical and administrative centre of the Armenian Church worldwide. This aspect information@ of the Feast is emphasized by the traditional title in Classical Armenian Soorp armenianchurch.oc.uk Etchmiadzini Gatoghiguh Yegeghetzin, “of Holy Etchmiadzin, the Universal Church.” Happy Birthday! 9Jagauor ;rknauor x:k;[;zi qo an,arv paf;a1 ;u x;rkrpagous ARMENIAN CHURCH YOUTH anouand qoum paf;a i .a[a[ouj;an0! “Heavenly King, preserve Your Church FELLOWSHIP (ACYF) unshaken, and keep the worshippers of your name in peace” (Armenian hymn). -

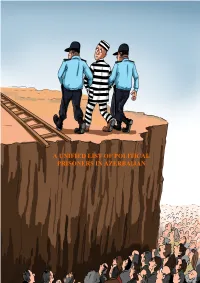

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh Visit Report

Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh Visit Report 7th– 14th August 2017 Welcome at The Lady Cox Rehabilitation Centre Photograph from the memorial for Fallen Soldiers titled ‘We Want Peace’ Humanitarian Aid Relief Trust Unit 1 Jubilee Business Centre 020 8205 4608 213 Kingsbury Road [email protected] London www.hart-uk.org NW9 8AQ Reg charity: 1107341 1 Executive Summary Aspects of the situation regarding Human Rights, military offences and the need for international monitors - Both The Republic of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh (also known as Artsakh) are taking steps to strengthen their democratic institutions, and the definition and protection of human rights in their constitutions. - Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh are concerned about the current global challenges relating to terrorism including Islamic State, and their vulnerable position in the South Caucasus region. - There is widespread concern over the escalation of Azerbaijan’s military arsenal. - There are extensive reports of the increasing propaganda in Azerbaijan to create “armenophobia” including anti-Armenian content in school text books and negative social media. - Political and human rights representatives in Nagorno-Karabakh highlight the urgent need for more international attention, including the presence of international monitors, to document first-hand evidence of aggression and to deter Azerbaijan from further military offences and perpetration of atrocities. - The spirit of the people in Nagorno-Karabakh is positive as they continue to rebuild their bomb- damaged towns and villages, often with impressive architecture style. Humanitarian Initiatives - The Government of Nagorno-Karabakh are making some of the newly built high-quality accommodation available for those suffering the legacy of war and people living with disabilities.