Range and Primary Habitats of Hawaiian Insular False Killer Whales: Informing Determination of Critical Habitat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of the Status of the Recreational Fishery for Ulua in Hawai‘I, and Recommendations for Future Management

Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Aquatic Resources Technical Report 20-02 Evaluation of the status of the recreational fishery for ulua in Hawai‘i, and recommendations for future management October 2000 Benjamin J. Cayetano Governor DIVISION OF AQUATIC RESOURCES Department of Land and Natural Resources 1151 Punchbowl Street, Room 330 Honolulu, HI 96813 November 2000 Cover photo by Kit Hinhumpetch Evaluation of the status of the recreational fishery for ulua in Hawai‘i, and recommendations for future management DAR Technical Report 20-02 “Ka ulua kapapa o ke kai loa” The ulua fish is a strong warrior. Hawaiian proverb “Kayden, once you get da taste fo’ ulua fishing’, you no can tink of anyting else!” From Ulua: The Musical, by Lee Cataluna Rick Gaffney and Associates, Inc. 73-1062 Ahikawa Street Kailua-Kona, Hawaii 96740 Phone: (808) 325-5000 Fax: (808) 325-7023 Email: [email protected] 3 4 Contents Introduction . 1 Background . 2 The ulua in Hawaiian culture . 2 Coastal fishery history since 1900 . 5 Ulua landings . 6 The ulua sportfishery in Hawai‘i . 6 Biology . 8 White ulua . 9 Other ulua . 9 Bluefin trevally movement study . 12 Economics . 12 Management options . 14 Overview . 14 Harvest refugia . 15 Essential fish habitat approach . 27 Community based management . 28 Recommendations . 29 Appendix . .32 Bibliography . .33 5 5 6 Introduction Unique marine resources, like Hawai‘i’s ulua/papio, have cultural, scientific, ecological, aes- thetic and functional values that are not generally expressed in commercial catch statistics and/or the market place. Where their populations have not been depleted, the various ulua pop- ular in Hawai‘i’s fisheries are often quite abundant and are thought to play the role of a signifi- cant predator in the ecology of nearshore marine ecosystems. -

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

213 Subpart I—Taking and Importing Marine Mammals

National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA, Commerce Pt. 218 regulations or that result in no more PART 218—REGULATIONS GOV- than a minor change in the total esti- ERNING THE TAKING AND IM- mated number of takes (or distribution PORTING OF MARINE MAM- by species or years), NMFS may pub- lish a notice of proposed LOA in the MALS FEDERAL REGISTER, including the asso- ciated analysis of the change, and so- Subparts A–B [Reserved] licit public comment before issuing the Subpart C—Taking Marine Mammals Inci- LOA. dental to U.S. Navy Marine Structure (c) A LOA issued under § 216.106 of Maintenance and Pile Replacement in this chapter and § 217.256 for the activ- Washington ity identified in § 217.250 may be modi- fied by NMFS under the following cir- 218.20 Specified activity and specified geo- cumstances: graphical region. (1) Adaptive Management—NMFS 218.21 Effective dates. may modify (including augment) the 218.22 Permissible methods of taking. existing mitigation, monitoring, or re- 218.23 Prohibitions. porting measures (after consulting 218.24 Mitigation requirements. with Navy regarding the practicability 218.25 Requirements for monitoring and re- porting. of the modifications) if doing so cre- 218.26 Letters of Authorization. ates a reasonable likelihood of more ef- 218.27 Renewals and modifications of Let- fectively accomplishing the goals of ters of Authorization. the mitigation and monitoring set 218.28–218.29 [Reserved] forth in the preamble for these regula- tions. Subpart D—Taking Marine Mammals Inci- (i) Possible sources of data that could dental to U.S. Navy Construction Ac- contribute to the decision to modify tivities at Naval Weapons Station Seal the mitigation, monitoring, or report- Beach, California ing measures in a LOA: (A) Results from Navy’s monitoring 218.30 Specified activity and specified geo- graphical region. -

ﻣﺎﻫﻲ ﮔﻴﺶ ﭘﻮزه دراز ( Carangoides Chrysophrys) در آﺑﻬﺎي اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن

A study on some biological aspects of longnose trevally (Carangoides chrysophrys) in Hormozgan waters Item Type monograph Authors Kamali, Easa; Valinasab, T.; Dehghani, R.; Behzadi, S.; Darvishi, M.; Foroughfard, H. Publisher Iranian Fisheries Science Research Institute Download date 10/10/2021 04:51:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/40061 وزارت ﺟﻬﺎد ﻛﺸﺎورزي ﺳﺎزﻣﺎن ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت، آﻣﻮزش و ﺗﺮوﻳﺞﻛﺸﺎورزي ﻣﻮﺳﺴﻪ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت ﻋﻠﻮم ﺷﻴﻼﺗﻲ ﻛﺸﻮر – ﭘﮋوﻫﺸﻜﺪه اﻛﻮﻟﻮژي ﺧﻠﻴﺞ ﻓﺎرس و درﻳﺎي ﻋﻤﺎن ﻋﻨﻮان: ﺑﺮرﺳﻲ ﺑﺮﺧﻲ از وﻳﮋﮔﻲ ﻫﺎي زﻳﺴﺖ ﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ﻣﺎﻫﻲ ﮔﻴﺶ ﭘﻮزه دراز ( Carangoides chrysophrys) در آﺑﻬﺎي اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﻣﺠﺮي: ﻋﻴﺴﻲ ﻛﻤﺎﻟﻲ ﺷﻤﺎره ﺛﺒﺖ 49023 وزارت ﺟﻬﺎد ﻛﺸﺎورزي ﺳﺎزﻣﺎن ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت، آﻣﻮزش و ﺗﺮوﻳﭻ ﻛﺸﺎورزي ﻣﻮﺳﺴﻪ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت ﻋﻠﻮم ﺷﻴﻼﺗﻲ ﻛﺸﻮر- ﭘﮋوﻫﺸﻜﺪه اﻛﻮﻟﻮژي ﺧﻠﻴﺞ ﻓﺎرس و درﻳﺎي ﻋﻤﺎن ﻋﻨﻮان ﭘﺮوژه : ﺑﺮرﺳﻲ ﺑﺮﺧﻲ از وﻳﮋﮔﻲ ﻫﺎي زﻳﺴﺖ ﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ﻣﺎﻫﻲ ﮔﻴﺶ ﭘﻮزه دراز (Carangoides chrysophrys) در آﺑﻬﺎي اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﺷﻤﺎره ﻣﺼﻮب ﭘﺮوژه : 2-75-12-92155 ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻧﮕﺎرﻧﺪه/ ﻧﮕﺎرﻧﺪﮔﺎن : ﻋﻴﺴﻲ ﻛﻤﺎﻟﻲ ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻣﺠﺮي ﻣﺴﺌﻮل ( اﺧﺘﺼﺎص ﺑﻪ ﭘﺮوژه ﻫﺎ و ﻃﺮﺣﻬﺎي ﻣﻠﻲ و ﻣﺸﺘﺮك دارد ) : ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻣﺠﺮي / ﻣﺠﺮﻳﺎن : ﻋﻴﺴﻲ ﻛﻤﺎﻟﻲ ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻫﻤﻜﺎر(ان) : ﺳﻴﺎﻣﻚ ﺑﻬﺰادي ،ﻣﺤﻤﺪ دروﻳﺸﻲ، ﺣﺠﺖ اﷲ ﻓﺮوﻏﻲ ﻓﺮد، ﺗﻮرج وﻟﻲﻧﺴﺐ، رﺿﺎ دﻫﻘﺎﻧﻲ ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻣﺸﺎور(ان) : - ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻧﺎﻇﺮ(ان) : - ﻣﺤﻞ اﺟﺮا : اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﺗﺎرﻳﺦ ﺷﺮوع : 92/10/1 ﻣﺪت اﺟﺮا : 1 ﺳﺎل و 6 ﻣﺎه ﻧﺎﺷﺮ : ﻣﻮﺳﺴﻪ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت ﻋﻠﻮم ﺷﻴﻼﺗﻲ ﻛﺸﻮر ﺗﺎرﻳﺦ اﻧﺘﺸﺎر : ﺳﺎل 1395 ﺣﻖ ﭼﺎپ ﺑﺮاي ﻣﺆﻟﻒ ﻣﺤﻔﻮظ اﺳﺖ . ﻧﻘﻞ ﻣﻄﺎﻟﺐ ، ﺗﺼﺎوﻳﺮ ، ﺟﺪاول ، ﻣﻨﺤﻨﻲ ﻫﺎ و ﻧﻤﻮدارﻫﺎ ﺑﺎ ذﻛﺮ ﻣﺄﺧﺬ ﺑﻼﻣﺎﻧﻊ اﺳﺖ . «ﺳﻮاﺑﻖ ﻃﺮح ﻳﺎ ﭘﺮوژه و ﻣﺠﺮي ﻣﺴﺌﻮل / ﻣﺠﺮي» ﭘﺮوژه : ﺑﺮرﺳﻲ ﺑﺮﺧﻲ از وﻳﮋﮔﻲ ﻫﺎي زﻳﺴﺖ ﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ﻣﺎﻫﻲ ﮔﻴﺶ ﭘﻮزه دراز ( Carangoides chrysophrys) در آﺑﻬﺎي اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﻛﺪ ﻣﺼﻮب : 2-75-12-92155 ﺷﻤﺎره ﺛﺒﺖ (ﻓﺮوﺳﺖ) : 49023 ﺗﺎرﻳﺦ : 94/12/28 ﺑﺎ ﻣﺴﺌﻮﻟﻴﺖ اﺟﺮاﻳﻲ ﺟﻨﺎب آﻗﺎي ﻋﻴﺴﻲ ﻛﻤﺎﻟﻲ داراي ﻣﺪرك ﺗﺤﺼﻴﻠﻲ ﻛﺎرﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ارﺷﺪ در رﺷﺘﻪ ﺑﻴﻮﻟﻮژي ﻣﺎﻫﻴﺎن درﻳﺎ ﻣﻲﺑﺎﺷﺪ. -

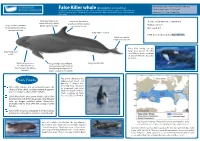

False Killer Whale Fact Sheet

False Killer whale (pseudorca crassidens) Adult length: Up to 6m (male)/5m (female) Distribution: coastal and primarily offshore waters in tropical and temperate regions (see map below and Adult weight: up to 2,000kg (m) full list of countries in the detailed species account online at: https://wwhandbook.iwc.int/en/species/false- Newborn: 1.6-1.9m /Unknown killer-whale Dark grey/black body Prominent dorsal fin is Threats: entanglement, contaminants colour with only a faintly usually curved and slightly Habitat: offshore Long, slender head tapers darker cape (variable) rounded at the tip to rounded snout with no Diet: squid, fish pronounced beak Body may be scarred IUCN Conservation status: Data deficient Flukes are small in relation to body size False killer whales can eat Head hangs over large prey species like this mouth Ono/Wahoo. photo courtesy of Daniel Webster, Cascadia Reserach Lighter grey anchor or Long strongly curved flipper Long, slender body “W” shaped patch on with a pronounced corner or chest between the flippers bend giving the flipper an ‘S’ (variable) shape – unique to this species This photo illustrates the Fun Facts bullet-shaped head and typically ‘S’ shaped flip- pers that help observers False killer whales are so named because the to distinguish false killer shape of their skulls, not their external appear- ance, is similar to that of killer whales. whales from pilot whales. Photo courtesy of Paula Like killer whales and sperm whales, false killer Olson/SEFSC/NOAA. whales form stable family groups, and females who no longer produce calves themselves probably help to look after the young of other females False killer whales participate in prey-sharing; a behaviour thought to reinforce social bonds False Killer whale distribution. -

Pseudorca Crassidens) and Nine Other Odontocete Species from Hawai‘I

Ecotoxicology DOI 10.1007/s10646-014-1300-0 Cytochrome P4501A1 expression in blubber biopsies of endangered false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) and nine other odontocete species from Hawai‘i Kerry M. Foltz • Robin W. Baird • Gina M. Ylitalo • Brenda A. Jensen Accepted: 2 August 2014 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014 Abstract Odontocetes (toothed whales) are considered insular false killer whale. Significantly higher levels of sentinel species in the marine environment because of their CYP1A1 were observed in false killer whales and rough- high trophic position, long life spans, and blubber that toothed dolphins compared to melon-headed whales, and in accumulates lipophilic contaminants. Cytochrome general, trophic position appears to influence CYP1A1 P4501A1 (CYP1A1) is a biomarker of exposure and expression patterns in particular species groups. No sig- molecular effects of certain persistent organic pollutants. nificant differences in CYP1A1 were found based on age Immunohistochemistry was used to visualize CYP1A1 class or sex across all samples. However, within male false expression in blubber biopsies collected by non-lethal killer whales, juveniles expressed significantly higher lev- sampling methods from 10 species of free-ranging els of CYP1A1 whenP compared to adults. Total polychlo- Hawaiian odontocetes: short-finned pilot whale, melon- rinated biphenyl ( PCBs) concentrations in 84 % of false headed whale, pygmy killer whale, common bottlenose killer whalesP exceeded proposed threshold levels for health dolphin, rough-toothed dolphin, pantropical spotted dol- effects, and PCBs correlated with CYP1A1 expression. phin, Blainville’s beaked whale, Cuvier’s beaked whale, There was no significant relationship between PCB toxic sperm whale, and endangered main Hawaiian Islands equivalent quotient and CYP1A1 expression, suggesting that this response may be influenced by agonists other than the dioxin-like PCBs measured in this study. -

False Killer Whale Dorsal Fin Disfigurements As A

False Killer Whale Dorsal Fin Disfigurements as a Possible Indicator of Long-Line Fishery Interactions in Hawaiian Waters1 Robin W. Baird 2 and Antoinette M. Gorgone3 Abstract: Scarring resulting from entanglement in fishing gear can be used to examine cetacean fishery interactions. False killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) are known to interact with the Hawai‘i-based tuna and swordfish long-line fish- ery in offshore Hawaiian waters. We examined the rate of major dorsal fin dis- figurements of false killer whales from nearshore waters around the main Hawaiian Islands to assess the likelihood that individuals around the main is- lands are part of the same population that interacts with the fishery. False killer whales were encountered on 11 occasions between 2000 and 2004, and 80 dis- tinctive individuals were photographically documented. Three of these (3.75%) had major dorsal fin disfigurements (two with the fins completely bent over and one missing the fin). Information from other research suggests that the rate of such disfigurements for our study population may be more than four times greater than for other odontocete populations. We suggest that the most likely cause of such disfigurements is interactions with longlines and that false killer whales found in nearshore waters around the main Hawaiian Islands are part of the same population that interacts with the fishery. Two of the animals docu- mented with disfigurements had infants in close attendance and were thought to be adult females. This implies that even with such injuries, at least some fe- males may be able to produce offspring, despite the importance of the dorsal fin in reproductive thermoregulation. -

Using Molecular Identification of Ichthyoplankton to Monitor

Molecular Identification of Ichthyoplankton in Cabo Pulmo National Park 1 Using molecular identification of ichthyoplankton to monitor 2 spawning activity in a subtropical no-take Marine Reserve 3 4 5 6 Ana Luisa M. Ahern1, *, Ronald S. Burton1, Ricardo J. Saldierna-Martínez2, Andrew F. Johnson1, 7 Alice E. Harada1, Brad Erisman1,4, Octavio Aburto-Oropeza1, David I. Castro Arvizú3, Arturo R. 8 Sánchez-Uvera2, Jaime Gómez-Gutiérrez2 9 10 11 12 1Marine Biology Research Division, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California 13 San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA 14 2Departamento de Plancton y Ecología Marina, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, 15 Instituto Politécnico Nacional, CP 23096, La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico 16 3Cabo Pulmo National Park, Baja California Sur, Mexico 17 4The University of Texas at Austin, Marine Science Institute, College of Natural Sciences, 18 Port Aransas, Texas, USA 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 *Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Molecular Identification of Ichthyoplankton in Cabo Pulmo National Park 26 ABSTRACT: Ichthyoplankton studies can provide valuable information on the species richness 27 and spawning activity of fishes, complementing estimations done using trawls and diver surveys. 28 Zooplankton samples were collected weekly between January and December 2014 in Cabo 29 Pulmo National Park, Gulf of California, Mexico (n=48). Fish larvae and particularly eggs are 30 difficult to identify morphologically, therefore the DNA barcoding method was employed to 31 identify 4,388 specimens, resulting in 157 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) corresponding 32 to species. Scarus sp., Halichoeres dispilus, Xyrichtys mundiceps, Euthynnus lineatus, 33 Ammodytoides gilli, Synodus lacertinus, Etrumeus acuminatus, Chanos chanos, Haemulon 34 flaviguttatum, and Vinciguerria lucetia were the most abundant and frequent species recorded. -

Peces De La Fauna De Acompañamiento En La Pesca Industrial De Camarón En El Golfo De California, México

Peces de la fauna de acompañamiento en la pesca industrial de camarón en el Golfo de California, México Juana López-Martínez1, Eloisa Herrera-Valdivia1, Jesús Rodríguez-Romero2 & Sergio Hernández-Vázquez2 1. Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, S.C. Km 2.35 Carretera a Las Tinajas, S/N Colonia Tinajas, Guaymas, Sonora, México C. P. 85460; [email protected], [email protected] 2. Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, S.C. Apdo. postal 128 La Paz, B.C.S. C.P. 23000; [email protected], [email protected] Recibido 19-VII-2009. Corregido 15-III-2010. Aceptado 16-IV-2010. Abstract: Bycatch fish species from shrimp industrial fishery in the Gulf of California, Mexico. The shrimp fishery in the Gulf of California is one the most important activities of revenue and employment for communi- ties. Nevertheless, this fishery has also created a large bycatch problem, principally fish. To asses this issue, a group of observers were placed on board the industrial shrimp fleet and evaluated the Eastern side of the Gulf during 2004 and 2005. Studies consisted on 20kg samples of the capture for each trawl, and made possible a sys- tematic list of species for this geographic area. Fish represented 70% of the capture. A total of 51 101 fish were collected, belonging to two classes, 20 orders, 65 families, 127 genera, and 241 species. The order Perciformes was the most diverse with 31 families, 78 genera, and 158 species. The best represented families by number of species were: Sciaenidae (34) and Paralichthyidae (18) and Haemulidae and Carangidae (16 each). -

Estructura Y Distribución De La Comunidad Íctica Acompañante En La Pesca Del Camarón (Golfo De Tehuantepec

Estructura y distribución de la comunidad íctica acompañante en la pesca del camarón (Golfo de Tehuantepec. Pacífico Oriental, México) Marco A. Martínez-Muñoz ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

Outrigger - Print

Outrigger - Print http://www.outrigger.com/explore/hawaiian-islands/view-from-... Hawaii Island's Best Beach for Snorkeling Kim Steutermann Rogers Friday, September 23, 2011 When I arrived at Hawaii Island’s number one snorkeling beach last week, the tide was low, revealing bright green seaweed growing on rocks. Exactly 77 beach-goers were out--reclining on beach towels, wading in the water, swimming and snorkeling. A dozen more sat at the picnic tables under the pavilion. Sean, a one-time public defender from California, manned the lifeguard tower, and two retired school teachers, Ken and Regan, set up shop for ReefTeach. On the back of Ken’s blue, volunteer-issue ReefTeach shirt, he’d handwritten in permanent marker: Please Kokua: No Touch Turtles!! No feed fish!! No touch coral!! *Mahalo*. Kahalu’u Bay is four-and-a-half acres in size. Some 400,000 visitors flock to this beach each year primarily for one thing: to snorkel. There are only three species of coral in the shallow bay and yet more than 100 species of reef fish have been identified here. That disparity indicates the fish are finding their nutrients in places other than just the reef—most likely delivered in the freshwater seeping through the sieve of an ocean floor, a bed of volcanic rock. As I read some of the table-top posters on display, a man approached Ken and Regan. He said that in 20 years of visiting and snorkeling Kahalu’u Bay he’d experienced something for the first time the day before. A humuhumunukunukuapua’a—Hawaii’s state fish, a Picasso triggerfish—had swum up to him and bit him in the knee. -

Marine Mammals of British Columbia Current Status, Distribution and Critical Habitats

Marine Mammals of British Columbia Current Status, Distribution and Critical Habitats John Ford and Linda Nichol Cetacean Research Program Pacific Biological Station Nanaimo, BC Outline • Brief (very) introduction to marine mammals of BC • Historical occurrence of whales in BC • Recent efforts to determine current status of cetacean species • Recent attempts to identify Critical Habitat for Threatened & Endangered species • Overview of pinnipeds in BC Marine Mammals of British Columbia - 25 Cetaceans, 5 Pinnipeds, 1 Mustelid Baleen Whales of British Columbia Family Balaenopteridae – Rorquals (5 spp) Blue Whale Balaenoptera musculus SARA Status = Endangered Fin Whale Balaenoptera physalus = Threatened = Spec. Concern Sei Whale Balaenoptera borealis Family Balaenidae – Right Whales (1 sp) Minke Whale Balaenoptera acutorostrata North Pacific Right Whale Eubalaena japonica Humpback Whale Megaptera novaeangliae Family Eschrichtiidae– Grey Whales (1 sp) Grey Whale Eschrichtius robustus Toothed Whales of British Columbia Family Physeteridae – Sperm Whales (3 spp) Sperm Whale Physeter macrocephalus Pygmy Sperm Whale Kogia breviceps Dwarf Sperm Whale Kogia sima Family Ziphiidae – Beaked Whales (4 spp) Hubbs’ Beaked Whale Mesoplodon carlhubbsii Stejneger’s Beaked Whale Mesoplodon stejnegeri Baird’s Beaked Whale Berardius bairdii Cuvier’s Beaked Whale Ziphius cavirostris Toothed Whales of British Columbia Family Delphinidae – Dolphins (9 spp) Pacific White-sided Dolphin Lagenorhynchus obliquidens Killer Whale Orcinus orca Striped Dolphin Stenella