Pseudorca Crassidens) and Nine Other Odontocete Species from Hawai‘I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

213 Subpart I—Taking and Importing Marine Mammals

National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA, Commerce Pt. 218 regulations or that result in no more PART 218—REGULATIONS GOV- than a minor change in the total esti- ERNING THE TAKING AND IM- mated number of takes (or distribution PORTING OF MARINE MAM- by species or years), NMFS may pub- lish a notice of proposed LOA in the MALS FEDERAL REGISTER, including the asso- ciated analysis of the change, and so- Subparts A–B [Reserved] licit public comment before issuing the Subpart C—Taking Marine Mammals Inci- LOA. dental to U.S. Navy Marine Structure (c) A LOA issued under § 216.106 of Maintenance and Pile Replacement in this chapter and § 217.256 for the activ- Washington ity identified in § 217.250 may be modi- fied by NMFS under the following cir- 218.20 Specified activity and specified geo- cumstances: graphical region. (1) Adaptive Management—NMFS 218.21 Effective dates. may modify (including augment) the 218.22 Permissible methods of taking. existing mitigation, monitoring, or re- 218.23 Prohibitions. porting measures (after consulting 218.24 Mitigation requirements. with Navy regarding the practicability 218.25 Requirements for monitoring and re- porting. of the modifications) if doing so cre- 218.26 Letters of Authorization. ates a reasonable likelihood of more ef- 218.27 Renewals and modifications of Let- fectively accomplishing the goals of ters of Authorization. the mitigation and monitoring set 218.28–218.29 [Reserved] forth in the preamble for these regula- tions. Subpart D—Taking Marine Mammals Inci- (i) Possible sources of data that could dental to U.S. Navy Construction Ac- contribute to the decision to modify tivities at Naval Weapons Station Seal the mitigation, monitoring, or report- Beach, California ing measures in a LOA: (A) Results from Navy’s monitoring 218.30 Specified activity and specified geo- graphical region. -

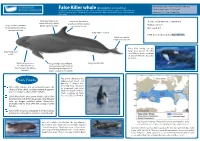

False Killer Whale Fact Sheet

False Killer whale (pseudorca crassidens) Adult length: Up to 6m (male)/5m (female) Distribution: coastal and primarily offshore waters in tropical and temperate regions (see map below and Adult weight: up to 2,000kg (m) full list of countries in the detailed species account online at: https://wwhandbook.iwc.int/en/species/false- Newborn: 1.6-1.9m /Unknown killer-whale Dark grey/black body Prominent dorsal fin is Threats: entanglement, contaminants colour with only a faintly usually curved and slightly Habitat: offshore Long, slender head tapers darker cape (variable) rounded at the tip to rounded snout with no Diet: squid, fish pronounced beak Body may be scarred IUCN Conservation status: Data deficient Flukes are small in relation to body size False killer whales can eat Head hangs over large prey species like this mouth Ono/Wahoo. photo courtesy of Daniel Webster, Cascadia Reserach Lighter grey anchor or Long strongly curved flipper Long, slender body “W” shaped patch on with a pronounced corner or chest between the flippers bend giving the flipper an ‘S’ (variable) shape – unique to this species This photo illustrates the Fun Facts bullet-shaped head and typically ‘S’ shaped flip- pers that help observers False killer whales are so named because the to distinguish false killer shape of their skulls, not their external appear- ance, is similar to that of killer whales. whales from pilot whales. Photo courtesy of Paula Like killer whales and sperm whales, false killer Olson/SEFSC/NOAA. whales form stable family groups, and females who no longer produce calves themselves probably help to look after the young of other females False killer whales participate in prey-sharing; a behaviour thought to reinforce social bonds False Killer whale distribution. -

False Killer Whale Dorsal Fin Disfigurements As A

False Killer Whale Dorsal Fin Disfigurements as a Possible Indicator of Long-Line Fishery Interactions in Hawaiian Waters1 Robin W. Baird 2 and Antoinette M. Gorgone3 Abstract: Scarring resulting from entanglement in fishing gear can be used to examine cetacean fishery interactions. False killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) are known to interact with the Hawai‘i-based tuna and swordfish long-line fish- ery in offshore Hawaiian waters. We examined the rate of major dorsal fin dis- figurements of false killer whales from nearshore waters around the main Hawaiian Islands to assess the likelihood that individuals around the main is- lands are part of the same population that interacts with the fishery. False killer whales were encountered on 11 occasions between 2000 and 2004, and 80 dis- tinctive individuals were photographically documented. Three of these (3.75%) had major dorsal fin disfigurements (two with the fins completely bent over and one missing the fin). Information from other research suggests that the rate of such disfigurements for our study population may be more than four times greater than for other odontocete populations. We suggest that the most likely cause of such disfigurements is interactions with longlines and that false killer whales found in nearshore waters around the main Hawaiian Islands are part of the same population that interacts with the fishery. Two of the animals docu- mented with disfigurements had infants in close attendance and were thought to be adult females. This implies that even with such injuries, at least some fe- males may be able to produce offspring, despite the importance of the dorsal fin in reproductive thermoregulation. -

Marine Mammal Taxonomy

Marine Mammal Taxonomy Kingdom: Animalia (Animals) Phylum: Chordata (Animals with notochords) Subphylum: Vertebrata (Vertebrates) Class: Mammalia (Mammals) Order: Cetacea (Cetaceans) Suborder: Mysticeti (Baleen Whales) Family: Balaenidae (Right Whales) Balaena mysticetus Bowhead whale Eubalaena australis Southern right whale Eubalaena glacialis North Atlantic right whale Eubalaena japonica North Pacific right whale Family: Neobalaenidae (Pygmy Right Whale) Caperea marginata Pygmy right whale Family: Eschrichtiidae (Grey Whale) Eschrichtius robustus Grey whale Family: Balaenopteridae (Rorquals) Balaenoptera acutorostrata Minke whale Balaenoptera bonaerensis Arctic Minke whale Balaenoptera borealis Sei whale Balaenoptera edeni Byrde’s whale Balaenoptera musculus Blue whale Balaenoptera physalus Fin whale Megaptera novaeangliae Humpback whale Order: Cetacea (Cetaceans) Suborder: Odontoceti (Toothed Whales) Family: Physeteridae (Sperm Whale) Physeter macrocephalus Sperm whale Family: Kogiidae (Pygmy and Dwarf Sperm Whales) Kogia breviceps Pygmy sperm whale Kogia sima Dwarf sperm whale DOLPHIN R ESEARCH C ENTER , 58901 Overseas Hwy, Grassy Key, FL 33050 (305) 289 -1121 www.dolphins.org Family: Platanistidae (South Asian River Dolphin) Platanista gangetica gangetica South Asian river dolphin (also known as Ganges and Indus river dolphins) Family: Iniidae (Amazon River Dolphin) Inia geoffrensis Amazon river dolphin (boto) Family: Lipotidae (Chinese River Dolphin) Lipotes vexillifer Chinese river dolphin (baiji) Family: Pontoporiidae (Franciscana) -

Genetic Variation and Evidence for Population Structure in Eastern North Pacific False Killer Whales (Pseudorca Crassidens)

783 Genetic variation and evidence for population structure in eastern North Pacific false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) Susan J. Chivers, Robin W. Baird, Daniel J. McSweeney, Daniel L. Webster, Nicole M. Hedrick, and Juan Carlos Salinas Abstract: False killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens (Owen, 1846)) are incidentally taken in the North Pacific pelagic long-line fishery, but little is known about their population structure to assess the impact of these takes. Using mito- chondrial DNA (mtDNA) control region sequence data, we quantified genetic variation for the species and tested for genetic differentiation among geographic strata. Our data set of 124 samples included 115 skin-biopsy samples col- lected from false killer whales inhabiting the eastern North Pacific Ocean (ENP), and nine samples collected from ani- mals sampled at sea or on the beach in the western North Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic oceans. Twenty-four (24) haplotypes were identified, and nucleotide diversity was low ( = 0.37%) but comparable with that of closely related species. Phylogeographic concordance in the distribution of haplotypes was revealed and a demographically isolated population of false killer whales associated with the main Hawaiian islands was identified (ÈST = 0.47, p < 0.0001). This result supports recognition of the existing management unit, which has geo-political boundaries corresponding to the USA’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Hawai‘i. However, a small number of animals sampled within the EEZ but away from the near-shore island area, which is defined as <25 nautical miles (1 nautical mile = 1.852 km) from shore, had haplotypes that were the same or closely related to those found elsewhere in the ENP, which suggests that there may be a second management unit within the Hawaiian EEZ. -

Marine Mammals of British Columbia Current Status, Distribution and Critical Habitats

Marine Mammals of British Columbia Current Status, Distribution and Critical Habitats John Ford and Linda Nichol Cetacean Research Program Pacific Biological Station Nanaimo, BC Outline • Brief (very) introduction to marine mammals of BC • Historical occurrence of whales in BC • Recent efforts to determine current status of cetacean species • Recent attempts to identify Critical Habitat for Threatened & Endangered species • Overview of pinnipeds in BC Marine Mammals of British Columbia - 25 Cetaceans, 5 Pinnipeds, 1 Mustelid Baleen Whales of British Columbia Family Balaenopteridae – Rorquals (5 spp) Blue Whale Balaenoptera musculus SARA Status = Endangered Fin Whale Balaenoptera physalus = Threatened = Spec. Concern Sei Whale Balaenoptera borealis Family Balaenidae – Right Whales (1 sp) Minke Whale Balaenoptera acutorostrata North Pacific Right Whale Eubalaena japonica Humpback Whale Megaptera novaeangliae Family Eschrichtiidae– Grey Whales (1 sp) Grey Whale Eschrichtius robustus Toothed Whales of British Columbia Family Physeteridae – Sperm Whales (3 spp) Sperm Whale Physeter macrocephalus Pygmy Sperm Whale Kogia breviceps Dwarf Sperm Whale Kogia sima Family Ziphiidae – Beaked Whales (4 spp) Hubbs’ Beaked Whale Mesoplodon carlhubbsii Stejneger’s Beaked Whale Mesoplodon stejnegeri Baird’s Beaked Whale Berardius bairdii Cuvier’s Beaked Whale Ziphius cavirostris Toothed Whales of British Columbia Family Delphinidae – Dolphins (9 spp) Pacific White-sided Dolphin Lagenorhynchus obliquidens Killer Whale Orcinus orca Striped Dolphin Stenella -

Pseudorca Crassidens (False Killer Whale)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Pseudorca crassidens (False Killer Whale) Family: Delphinidae (Oceanic Dolphins and Killer Whales) Order: Cetacea (Whales and Dolphins) Class: Mammalia (Mammals) Fig. 1. False killer whale, Pseudorca crassidens. [http://ocean.si.edu/ocean-photos/killer-whale-imposter, downloaded 31 October 2015] TRAITS. Pseudorca crassidens is at the upper size range within its family (Delphinidae); males can be as much as 6.1m and females 4.9m in head and body length (Nowak, 1999). Both sexes weigh in at around 700kg (NOAA Fisheries, 2013) although they can reach a maximum weight of 1360kg (Nowak, 1999). Newly born offspring are typically no longer than 1.8m and are only a fraction of an adult’s weight (Leatherwood, 1988). The false killer whale has a bulb or melon feature on its forehead (Fig. 1) which is slightly larger in males, and a narrow head which tapers into its slightly elongated and rounded snout. The jaws of P. crassidens hold 8-11 pairs of thick teeth and have an overhang, with the upper jaw protruding forward past the lower jaw. The thin sickle shaped dorsal fin of the false killer whale is also slightly tapered and can measure as much as 40cm tall (Leatherwood, 1988; Nowak, 1999). The pectoral flippers have a characteristic UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour shape unique in its family, with a bulge on the front edge. Sexual dimorphism also occurs in the skull with size variation between male and female which measure 58-65cm and 55-59cm respectively. -

List of Marine Mammal Species & Subspecies

List of Marine Mammal Species & Subspecies The Committee on Taxonomy, chaired by Bill Perrin, produced the first official Society for Marine Mammalogy list of marine mammal species and subspecies in 2010 . Consensus on some issues was not possible; this is reflected in the footnotes. The list is updated annually. This version was updated in October 2015. This list can be cited as follows: “Committee on Taxonomy. 2015. List of marine mammal species and subspecies. Society for Marine Mammalogy, www.marinemammalscience.org, consulted on [date].” This list includes living and recently extinct (within historical times) species and subspecies, named and un-named. It is meant to reflect prevailing usage and recent revisions published in the peer-reviewed literature. An un-named subspecies is included if author(s) of a peer-reviewed article stated explicitly that the form is likely an undescribed subspecies. The Committee omits some described species and subspecies because of concern about their biological distinctness; reservations are given below. Author(s) and year of description of the species follow the Latin species name; when these are enclosed in parentheses, the species was originally described in a different genus. Classification and scientific names follow Rice (1998), with adjustments reflecting more recent literature. Common names are arbitrary and change with time and place; one or two currently frequently used names in English and/or a range language are given here. Additional English common names and common names in French, Spanish, Russian and other languages are available at www.marinespecies.org/cetacea/. Species and subspecies are listed in alphabetical order within families. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

A Review of False Killer Whales in Hawaiian Waters: Biology, Status, and Risk Factors

A review of false killer whales in Hawaiian waters: biology, status, and risk factors Robin W. Baird Cascadia Research Collective 218 ½ West Fourth Avenue Olympia, WA 98501 [email protected] Report prepared for the U.S. Marine Mammal Commission under Order No. E40475499 December 23, 2009 False killer whales in Hawai‘i 1. Executive Summary.................................................................................................................. 2 2. Introduction............................................................................................................................... 3 3. Biology of false killer whales.................................................................................................... 3 4. False killer whales in Hawaiian waters................................................................................... 5 4.A. Population structure ........................................................................................................... 7 4.B. Population ranges, individual movements, and potential boundaries/overlap............... 10 4.C. Estimates of abundance/population size.......................................................................... 12 4.D. Population trends.............................................................................................................. 15 4.E. Social organization and group structure ......................................................................... 17 4.F. Diet and foraging ecology................................................................................................ -

Pseudorca Crassidens – False Killer Whale

Pseudorca crassidens – False Killer Whale variation is not uncommon in cetaceans (Kitchener et al. 1990; Connor et al. 2000), and is likely attributed to changes in water temperature and prey distribution. Results exhibiting geographic variation in body size were found between Japanese and southern African populations, where Japanese specimens were significantly larger in comparison (Ferreira 2008), confirming previous suggestions that Southern Hemisphere populations are typically smaller and reach sexual maturity at shorter body lengths, compared to those of the northern hemisphere (Purves & Pilleri 1978; Kasuya 1986). Using mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) control region sequence data Chivers et al. (2007) describe a demographically isolated population of False Killer Whales in the waters off Hawaii, in the eastern North Pacific. Regional Red List status (2016) Least Concern National Red List status (2004) Least Concern Assessment Rationale Global and regional population trends and abundance Reasons for change No change data is unavailable for this species, and it is considered Global Red List status (2008) Data Deficient elusive and rare in the waters of the assessment region. Although, occasional mass stranding events have been TOPS listing (NEMBA) (2007) None documented in South Africa, it is suspected that these are CITES listing (2003) Appendix II accredited to natural causes, rather than anthropogenic activities. No major threats that may cause substantial Endemic No population depletion, have been identified, resultantly, this species