False Killer Whale Dorsal Fin Disfigurements As a Possible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Mammals of Hudson Strait the Following Marine Mammals Are Common to Hudson Strait, However, Other Species May Also Be Seen

Marine Mammals of Hudson Strait The following marine mammals are common to Hudson Strait, however, other species may also be seen. It’s possible for marine mammals to venture outside of their common habitats and may be seen elsewhere. Bowhead Whale Length: 13-19 m Appearance: Stocky, with large head. Blue-black body with white markings on the chin, belly and just forward of the tail. No dorsal fin or ridge. Two blow holes, no teeth, has baleen. Behaviour: Blow is V-shaped and bushy, reaching 6 m in height. Often alone but sometimes in groups of 2-10. Habitat: Leads and cracks in pack ice during winter and in open water during summer. Status: Special concern Beluga Whale Length: 4-5 m Appearance: Adults are almost entirely white with a tough dorsal ridge and no dorsal fin. Young are grey. Behaviour: Blow is low and hardly visible. Not much of the body is visible out of the water. Found in small groups, but sometimes hundreds to thousands during annual migrations. Habitat: Found in open water year-round. Prefer shallow coastal water during summer and water near pack ice in winter. Killer Whale Status: Endangered Length: 8-9 m Appearance: Black body with white throat, belly and underside and white spot behind eye. Triangular dorsal fin in the middle of the back. Male dorsal fin can be up to 2 m in high. Behaviour: Blow is tall and column shaped; approximately 4 m in height. Narwhal Typically form groups of 2-25. Length: 4-5 m Habitat: Coastal water and open seas, often in water less than 200 m depth. -

Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus Orca) Cover: Aerial Photograph of a Mother and New Calf in SRKW J-Pod, Taken in September 2020

SPECIES in the SPOTLIGHT Priority Actions 2021–2025 Southern Resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) Cover: Aerial photograph of a mother and new calf in SRKW J-pod, taken in September 2020. The photo was obtained using a non-invasive octocopter drone at >100 ft. Photo: Holly Fearnbach (SR3, SeaLife Response, Rehab and Research) and Dr. John Durban (SEA, Southall Environmental Associates); collected under NMFS research permit #19091. Species in the Spotlight: Southern Resident Killer Whales | PRIORITY ACTIONS: 2021–2025 Central California Coast coho salmon adult, Lagunitas Creek. Photo: Mt. Tamalpais Photos. Passengers aboard a Washington State Ferry view Southern Resident killer whales in Puget Sound, an example of low-impact whale watching. Photo: NWFSC. The Species in the Spotlight Initiative In 2015, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries) launched the Species in the Spotlight initiative to provide immediate, targeted efforts to halt declines and stabilize populations, focus resources within and outside of NOAA on the most at-risk species, guide agency actions where we have discretion to make investments, increase public awareness and support for these species, and expand partnerships. We have renewed the initiative for 2021–2025. U.S. Department of Commerce | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | National Marine Fisheries Service 1 Species in the Spotlight: Southern Resident Killer Whales | PRIORITY ACTIONS: 2021–2025 The criteria for Species in the Spotlight are that they partnerships, and prioritizing funding—providing or are endangered, their populations are declining, and leveraging more than $113 million toward projects that they are considered a recovery priority #1C (84 FR will help stabilize these highly at-risk species. -

Commonly Found Marine Mammals of Puget Sound

Marine Mammals of Puget Sound Pinnipeds: Seals & Sea Lions Cetaceans: Pacific Harbor Seal Whales, Dolphins & Porpoise Phoca vitulina Adults mottled tan or blue-gray with dark spots Seal Pups Orca Male: 6'/300 lbs; Female: 5'/200 pounds Earless (internal ears, with externally visible hole) (or Killer Whale) Short fur-covered flippers, nails at end Drags rear flippers behind body Orcinus orca Vocalization: "maah" (pups only) Black body with white chin, Most common marine mammal in Puget Sound belly, and eyepatch Shy, but curious. Pupping occurs June/July in Average 23 - 26'/4 - 8 tons the Strait of Juan de Fuca and San Juan Islands Southern Resident orcas (salmon-eating) are Endangered, travel in larger pods Northern Elephant Seal If you see a seal pup Transient (marine mammal -eating) orcas alone on the beach travel in smaller pods Orcas are most often observed in inland waters Mirounga angustirostris DO NOT DISTURB - fall - spring; off San Juan Islands in summer Brownish-gray it’s the law! Dall's Porpoise Male: 10-12'/4,000-5,000 lbs Human encroachment can stress the pup Female: 8-9'/900-1,000 lbs. Phocoenoides dalli and scare the mother away. Internal ears (slight hole) For your safety and the health of the pup, Harbor Porpoise Black body/white belly and sides Short fur-covered flippers, nails at end leave the pup alone. Do not touch! White on dorsal fin trailing edge Drags rear flippers behind body Phocoena phocoena Average 6 - 7'/300 lbs. Vocalization: Guttural growl or belch Dark gray or black Travels alone or in groups of 2 - 20 or more Elephant seals are increasing in with lighter sides and belly Creates “rooster tail” spray, number in this region Average 5- 6'/120 lbs. -

Sustained Disruption of Narwhal Habitat Use and Behavior in The

Sustained disruption of narwhal habitat use and behavior in the presence of Arctic killer whales Greg A. Breeda,1, Cory J. D. Matthewsb, Marianne Marcouxb, Jeff W. Higdonc, Bernard LeBlancd, Stephen D. Petersene, Jack Orrb, Natalie R. Reinhartf, and Steven H. Fergusonb aInstitute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK 99775; bArctic Aquatic Research Division, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Winnipeg, MB, Canada R3T 2N6; cHigdon Wildlife Consulting, Winnipeg, MB, Canada R3G 3C9; dFisheries Management, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Quebec, QC, Canada G1K 7Y7; eAssiniboine Park Zoo, Winnipeg, MB, Canada R3R 0B8; and fDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada R3T 2N2 Edited by James A. Estes, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, and approved January 10, 2017 (received for review July 17, 2016) Although predators influence behavior of prey, analyses of elec- Electronic tracking tags are also frequently used to track verte- tronic tracking data in marine environments rarely consider how brates in marine systems. Although there is evidence that marine predators affect the behavior of tracked animals. We collected animals adjust their behavior under predation threat (21, 22, 12), an unprecedented dataset by synchronously tracking predator few data or analyses exist showing how predators affect the (killer whales, N = 1; representing a family group) and prey movement of tracked marine animals. These data are lacking (narwhal, N = 7) via satellite telemetry in Admiralty Inlet, a because marine environments are more difficult to observe and large fjord in the Eastern Canadian Arctic. Analyzing the move- tracked animals often move over scales much larger than their ment data with a switching-state space model and a series of terrestrial counterparts, making it difficult to measure predator mixed effects models, we show that the presence of killer whales density in situations where tracking tags are deployed on prey. -

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

Genetic Structure of the Beaked Whale Genus Berardius in the North Pacific

MARINE MAMMAL SCIENCE, 33(1): 96–111 (January 2017) Published 2016. This article is a U.S. Government work and is in the public domain in the USA DOI: 10.1111/mms.12345 Genetic structure of the beaked whale genus Berardius in the North Pacific, with genetic evidence for a new species PHILLIP A. MORIN1, Marine Mammal and Turtle Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Cen- ter, National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, 8901 La Jolla Shores Drive, La Jolla, California 92037, U.S.A. and Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92037, U.S.A.; C. SCOTT BAKER Marine Mammal Institute and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, 2030 SE Marine Science Drive, Newport, Oregon 07365, U.S.A.; REID S. BREWER Fisheries Technology, University of Alaska South- east, 1332 Seward Avenue, Sitka, Alaska 99835, U.S.A.; ALEXANDER M. BURDIN Kam- chatka Branch of the Pacific Geographical Institute, Partizanskaya Str. 6, Petropavlovsk- Kamchatsky, 683000 Russia; MEREL L. DALEBOUT School of Biological, Earth, and Environ- mental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia; JAMES P. DINES Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, U.S.A.; IVAN D. FEDUTIN AND OLGA A. FILATOVA Faculty of Biology, Moscow State University, Moscow 119992, Russia; ERICH HOYT Whale and Dol- phin Conservation, Park House, Allington Park, Bridport, Dorset DT6 5DD, United King- dom; JEAN-LUC JUNG Laboratoire BioGEMME, Universite de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, France; MORGANE LAUF Marine Mammal and Turtle Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, 8901 La Jolla Shores Drive, La Jolla, California 92037, U.S.A.; CHARLES W. -

Climate Change Could Impact Narwhal Consumption by Killer Whales

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Student Publications, Projects, and Scientific Communication News Performances 2020 Climate Change Could Impact Narwhal Consumption by Killer Whales Mykenzee L. Munaco Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/sci-com-news Part of the Biology Commons, Earth Sciences Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, Marine Biology Commons, Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Munaco, Mykenzee L., "Climate Change Could Impact Narwhal Consumption by Killer Whales" (2020). Scientific Communication News. 27. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/sci-com-news/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications, Projects, and Performances at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scientific Communication News yb an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Climate Change Could Impact Narwhal Consumption by Killer Whales Climate change related differences in killer whale distributions could result in increased predation of narwhals in the northern Baffin Island region. SOURCE: Wiley: Global Change Biology By Mykenzee Munaco 05 November 2020 Climate change is creating warmer ocean temperatures and melting sea ice at polar latitudes. These environmental changes can allow species to expand their normal range to higher latitudes. Killer whales have recently been observed at higher latitudes than they have historically resided in. As a result, there is concern that the narwhal population could experience higher rates of killer whale predation, potentially resulting in the decline of important narwhal populations. Transient killer whales eat marine mammals and are known to visit the Canadian Arctic in summer months. -

213 Subpart I—Taking and Importing Marine Mammals

National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA, Commerce Pt. 218 regulations or that result in no more PART 218—REGULATIONS GOV- than a minor change in the total esti- ERNING THE TAKING AND IM- mated number of takes (or distribution PORTING OF MARINE MAM- by species or years), NMFS may pub- lish a notice of proposed LOA in the MALS FEDERAL REGISTER, including the asso- ciated analysis of the change, and so- Subparts A–B [Reserved] licit public comment before issuing the Subpart C—Taking Marine Mammals Inci- LOA. dental to U.S. Navy Marine Structure (c) A LOA issued under § 216.106 of Maintenance and Pile Replacement in this chapter and § 217.256 for the activ- Washington ity identified in § 217.250 may be modi- fied by NMFS under the following cir- 218.20 Specified activity and specified geo- cumstances: graphical region. (1) Adaptive Management—NMFS 218.21 Effective dates. may modify (including augment) the 218.22 Permissible methods of taking. existing mitigation, monitoring, or re- 218.23 Prohibitions. porting measures (after consulting 218.24 Mitigation requirements. with Navy regarding the practicability 218.25 Requirements for monitoring and re- porting. of the modifications) if doing so cre- 218.26 Letters of Authorization. ates a reasonable likelihood of more ef- 218.27 Renewals and modifications of Let- fectively accomplishing the goals of ters of Authorization. the mitigation and monitoring set 218.28–218.29 [Reserved] forth in the preamble for these regula- tions. Subpart D—Taking Marine Mammals Inci- (i) Possible sources of data that could dental to U.S. Navy Construction Ac- contribute to the decision to modify tivities at Naval Weapons Station Seal the mitigation, monitoring, or report- Beach, California ing measures in a LOA: (A) Results from Navy’s monitoring 218.30 Specified activity and specified geo- graphical region. -

Killer Whale) Orcinus Orca

AMERICAN CETACEAN SOCIETY FACT SHEET P.O. Box 1391 - San Pedro, CA 90733-1391 - (310) 548-6279 ORCA (Killer Whale) Orcinus orca CLASS: Mammalia ORDER: Cetacea SUBORDER: Odontoceti FAMILY: Delphinidae GENUS: Orcinus SPECIES: orca The orca, or killer whale, with its striking black and white coloring, is one of the best known of all the cetaceans. It has been extensively studied in the wild and is often the main attraction at many sea parks and aquaria. An odontocete, or toothed whale, the orca is known for being a carnivorous, fast and skillful hunter, with a complex social structure and a cosmopolitan distribution (orcas are found in all the oceans of the world). Sometimes called "the wolf of the sea", the orca can be a fierce hunter with well-organized hunting techniques, although there are no documented cases of killer whales attacking a human in the wild. PHYSICAL SHAPE The orca is a stout, streamlined animal. It has a round head that is tapered, with an indistinct beak and straight mouthline. COLOR The orca has a striking color pattern made up of well-defined areas of shiny black and cream or white. The dorsal (top) part of its body is black, with a pale white to gray "saddle" behind the dorsal fin. It has an oval, white eyepatch behind and above each eye. The chin, throat, central length of the ventral (underside) area, and undersides of the tail flukes are white. Each whale can be individually identified by its markings and by the shape of its saddle patch and dorsal fin. -

EMBRACE YOUR SCARS a SCAR Is Your Skin’S Natural Way of Knitting Itself Back Worry About Scars? Together After It’S Been Hurt

ASK THE Experts own skin. We asked two of our Skin Cancer Founda- Mohs surgery on certain cases of melanoma, but tion member physicians to share their expertise on this requires additional training. Patients with more Healing everything you need to know to be scar-savvy, from advanced melanomas may require additional treat- wound care to scar repair. ments, such as radiation or medications, including immunotherapies and targeted therapies. What is a scar, exactly? How much do patients EMBRACE YOUR SCARS A SCAR is your skin’s natural way of knitting itself back worry about scars? together after it’s been hurt. Healing is a multipart pro- If you have a scar, congratulations! Think of it as a badge of courage and healing. cess, and the science behind it is complex. Dermatolog- WHEN DOCTORS tell patients they need skin cancer Our expert dermatologists tell how to nurture a new scar to get the ic surgeon Mary-Margaret Kober, MD, who practices surgery, they hear a wide range of reactions, says Dr. in Santa Rosa, California, helps explain it in simple Kober. “I have some patients who say, ‘I don’t care best outcome — and, if needed, how to fix an old scar to make it look better. terms. Wherever there’s been an injury, she says, the about the scar, Doc. I don’t have a modeling career. by Julie Bain first thing that happens is that blood cells called plate- Just get the cancer out.’ That’s one extreme.” There lets gather together and form a clot to stop the bleed- are also patients on the other side of the spectrum, ing and seal the wound. -

Sunday, 11 April 2021 John 20:19-31 Pr Gus Schutz 'Then He Said

Sunday, 11 April 2021 John 20:19-31 Pr Gus Schutz ‘Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe.”’ The scars of Jesus were very important for Thomas. It can be easy to be a little hard on Thomas. I think tradition has done that. Put yourself in his situation. Wouldn’t you also want some visible proof to connect what you see with the events of Good Friday? So that you can know without doubt that this really is the same Jesus who was hung up on the cross? The truth is the scars of Jesus were important for all the disciples. They confirmed to them that it truly was Jesus. In the same body, now risen and transformed. • When Jesus first appeared to the disciples, Luke tells us: “they were startled and frightened and thought they saw a spirit.” (Luke 24:37) Then he showed them his scars, saying to them: “Look at my hands and my feet. It is I myself! Touch me and see; a ghost does not have flesh and bones, as you see I have.” (Luke 24:39) • The apostle John reports that Jesus: “showed them his hands and feet” (John 20:20) This was the first time, when Thomas was not with them. So he insisted he must see the scars when it was reported to him that the others had seen Jesus. Eight days later the wish and prayer of Thomas was answered. Jesus offered him his scars, saying: “Put your finger here; see my hands. -

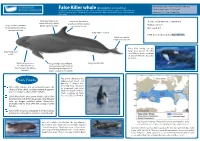

False Killer Whale Fact Sheet

False Killer whale (pseudorca crassidens) Adult length: Up to 6m (male)/5m (female) Distribution: coastal and primarily offshore waters in tropical and temperate regions (see map below and Adult weight: up to 2,000kg (m) full list of countries in the detailed species account online at: https://wwhandbook.iwc.int/en/species/false- Newborn: 1.6-1.9m /Unknown killer-whale Dark grey/black body Prominent dorsal fin is Threats: entanglement, contaminants colour with only a faintly usually curved and slightly Habitat: offshore Long, slender head tapers darker cape (variable) rounded at the tip to rounded snout with no Diet: squid, fish pronounced beak Body may be scarred IUCN Conservation status: Data deficient Flukes are small in relation to body size False killer whales can eat Head hangs over large prey species like this mouth Ono/Wahoo. photo courtesy of Daniel Webster, Cascadia Reserach Lighter grey anchor or Long strongly curved flipper Long, slender body “W” shaped patch on with a pronounced corner or chest between the flippers bend giving the flipper an ‘S’ (variable) shape – unique to this species This photo illustrates the Fun Facts bullet-shaped head and typically ‘S’ shaped flip- pers that help observers False killer whales are so named because the to distinguish false killer shape of their skulls, not their external appear- ance, is similar to that of killer whales. whales from pilot whales. Photo courtesy of Paula Like killer whales and sperm whales, false killer Olson/SEFSC/NOAA. whales form stable family groups, and females who no longer produce calves themselves probably help to look after the young of other females False killer whales participate in prey-sharing; a behaviour thought to reinforce social bonds False Killer whale distribution.