Lin Et Al. 2013A; Lin Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remodeling Adipose Tissue Through in Silico Modulation of Fat Storage For

Chénard et al. BMC Systems Biology (2017) 11:60 DOI 10.1186/s12918-017-0438-9 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Remodeling adipose tissue through in silico modulation of fat storage for the prevention of type 2 diabetes Thierry Chénard2, Frédéric Guénard3, Marie-Claude Vohl3,4, André Carpentier5, André Tchernof4,6 and Rafael J. Najmanovich1* Abstract Background: Type 2 diabetes is one of the leading non-infectious diseases worldwide and closely relates to excess adipose tissue accumulation as seen in obesity. Specifically, hypertrophic expansion of adipose tissues is related to increased cardiometabolic risk leading to type 2 diabetes. Studying mechanisms underlying adipocyte hypertrophy could lead to the identification of potential targets for the treatment of these conditions. Results: We present iTC1390adip, a highly curated metabolic network of the human adipocyte presenting various improvements over the previously published iAdipocytes1809. iTC1390adip contains 1390 genes, 4519 reactions and 3664 metabolites. We validated the network obtaining 92.6% accuracy by comparing experimental gene essentiality in various cell lines to our predictions of biomass production. Using flux balance analysis under various test conditions, we predict the effect of gene deletion on both lipid droplet and biomass production, resulting in the identification of 27 genes that could reduce adipocyte hypertrophy. We also used expression data from visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues to compare the effect of single gene deletions between adipocytes from each -

METABOLIC EVOLUTION in GALDIERIA SULPHURARIA By

METABOLIC EVOLUTION IN GALDIERIA SULPHURARIA By CHAD M. TERNES Bachelor of Science in Botany Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2009 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2015 METABOLIC EVOLUTION IN GALDIERIA SUPHURARIA Dissertation Approved: Dr. Gerald Schoenknecht Dissertation Adviser Dr. David Meinke Dr. Andrew Doust Dr. Patricia Canaan ii Name: CHAD M. TERNES Date of Degree: MAY, 2015 Title of Study: METABOLIC EVOLUTION IN GALDIERIA SULPHURARIA Major Field: PLANT SCIENCE Abstract: The thermoacidophilic, unicellular, red alga Galdieria sulphuraria possesses characteristics, including salt and heavy metal tolerance, unsurpassed by any other alga. Like most plastid bearing eukaryotes, G. sulphuraria can grow photoautotrophically. Additionally, it can also grow solely as a heterotroph, which results in the cessation of photosynthetic pigment biosynthesis. The ability to grow heterotrophically is likely correlated with G. sulphuraria ’s broad capacity for carbon metabolism, which rivals that of fungi. Annotation of the metabolic pathways encoded by the genome of G. sulphuraria revealed several pathways that are uncharacteristic for plants and algae, even red algae. Phylogenetic analyses of the enzymes underlying the metabolic pathways suggest multiple instances of horizontal gene transfer, in addition to endosymbiotic gene transfer and conservation through ancestry. Although some metabolic pathways as a whole appear to be retained through ancestry, genes encoding individual enzymes within a pathway were substituted by genes that were acquired horizontally from other domains of life. Thus, metabolic pathways in G. sulphuraria appear to be composed of a ‘metabolic patchwork’, underscored by a mosaic of genes resulting from multiple evolutionary processes. -

Rational Design of Resveratrol O-Methyltransferase for the Production of Pinostilbene

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Rational Design of Resveratrol O-methyltransferase for the Production of Pinostilbene Daniela P. Herrera 1 , Andrea M. Chánique 1,2 , Ascensión Martínez-Márquez 3, Roque Bru-Martínez 3 , Robert Kourist 2 , Loreto P. Parra 4,* and Andreas Schüller 4,5,* 1 Department of Chemical and Bioprocesses Engineering, School of Engineering, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Santiago 7820244, Chile; [email protected] (D.P.H.); [email protected] (A.M.C.) 2 Institute of Molecular Biotechnology, Graz University of Technology, Petersgasse 14, 8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected] 3 Department of Agrochemistry and Biochemistry, Faculty of Science and Multidisciplinary Institute for Environmental Studies “Ramon Margalef”, University of Alicante, 03690 Alicante, Spain; [email protected] (A.M.-M.); [email protected] (R.B.-M.) 4 Institute for Biological and Medical Engineering, Schools of Engineering, Medicine and Biological Sciences, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Santiago 7820244, Chile 5 Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, School of Biological Sciences, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Av. Libertador Bernardo O’Higgins 340, Santiago 8320000, Chile * Correspondence: [email protected] (L.P.P.); [email protected] (A.S.) Abstract: Pinostilbene is a monomethyl ether analog of the well-known nutraceutical resveratrol. Both compounds have health-promoting properties, but the latter undergoes rapid metabolization and has low bioavailability. O-methylation improves the stability and bioavailability of resveratrol. In plants, these reactions are performed by O-methyltransferases (OMTs). Few efficient OMTs that Citation: Herrera, D.P.; Chánique, monomethylate resveratrol to yield pinostilbene have been described so far. -

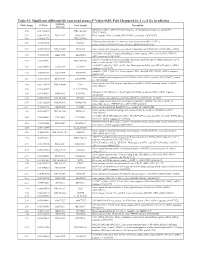

Table 2. Significant

Table 2. Significant (Q < 0.05 and |d | > 0.5) transcripts from the meta-analysis Gene Chr Mb Gene Name Affy ProbeSet cDNA_IDs d HAP/LAP d HAP/LAP d d IS Average d Ztest P values Q-value Symbol ID (study #5) 1 2 STS B2m 2 122 beta-2 microglobulin 1452428_a_at AI848245 1.75334941 4 3.2 4 3.2316485 1.07398E-09 5.69E-08 Man2b1 8 84.4 mannosidase 2, alpha B1 1416340_a_at H4049B01 3.75722111 3.87309653 2.1 1.6 2.84852656 5.32443E-07 1.58E-05 1110032A03Rik 9 50.9 RIKEN cDNA 1110032A03 gene 1417211_a_at H4035E05 4 1.66015788 4 1.7 2.82772795 2.94266E-05 0.000527 NA 9 48.5 --- 1456111_at 3.43701477 1.85785922 4 2 2.8237185 9.97969E-08 3.48E-06 Scn4b 9 45.3 Sodium channel, type IV, beta 1434008_at AI844796 3.79536664 1.63774235 3.3 2.3 2.75319499 1.48057E-08 6.21E-07 polypeptide Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RIKEN cDNA 2310040G17 gene 1417619_at 4 3.38875643 1.4 2 2.69163229 8.84279E-06 0.0001904 BC056474 15 12.1 Mus musculus cDNA clone 1424117_at H3030A06 3.95752801 2.42838452 1.9 2.2 2.62132809 1.3344E-08 5.66E-07 MGC:67360 IMAGE:6823629, complete cds NA 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1454696_at -3.46081884 -4 -1.3 -1.6 -2.6026947 8.58458E-05 0.0012617 beta 1 Gnb1 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1417432_a_at H3094D02 -3.13334396 -4 -1.6 -1.7 -2.5946297 1.04542E-05 0.0002202 beta 1 Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RAD23a homolog (S. -

WO 2013/064736 Al 10 May 2013 (10.05.2013) P O P CT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/064736 Al 10 May 2013 (10.05.2013) P O P CT (51) International Patent Classification: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, C12N 9/10 (2006.01) DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (21) International Application Number: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, PCT/FI2012/05 1048 ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, (22) International Filing Date: NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, 3 1 October 2012 (3 1.10.2012) RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, (25) Filing Language: English ZM, ZW. (26) Publication Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 201 16074 1 November 201 1 (01. 11.201 1) FI GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (71) Applicant: VALIO LTD [FI/FI]; Meijeritie 6, FI-00370 TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Helsinki (FI). EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, (72) Inventors: RAJAKARI, Kirsi; c/o Valio Ltd, Meijeritie 6, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, FI-00370 Helsinki (FI). -

Biosynthetic Investigation of Phomopsins Reveals a Widespread Pathway for Ribosomal Natural Products in Ascomycetes

Biosynthetic investigation of phomopsins reveals a widespread pathway for ribosomal natural products in Ascomycetes Wei Dinga, Wan-Qiu Liua, Youli Jiaa, Yongzhen Lia, Wilfred A. van der Donkb,c,1, and Qi Zhanga,b,1 aDepartment of Chemistry, Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China; bDepartment of Chemistry, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801; and cHoward Hughes Medical Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801 Edited by Jerrold Meinwald, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, and approved February 23, 2016 (received for review November 24, 2015) Production of ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally mod- dehydroaspartic acid, 3,4-dehydroproline, and 3,4-dehydrovaline ified peptides (RiPPs) has rarely been reported in fungi, even (Fig. 1A). though organisms of this kingdom have a long history as a prolific Early isotopic labeling studies showed that Ile, Pro, and Phe were source of natural products. Here we report an investigation of the all incorporated into the phomopsin scaffold (24). Because a Phe phomopsins, antimitotic mycotoxins. We show that phomopsin is a hydroxylase that can convert Phe to Tyr has not been found in fungal RiPP and demonstrate the widespread presence of a path- Ascomycetes, the labeling study seems incongruent with a ribosomal way for the biosynthesis of a family of fungal cyclic RiPPs, which we route to phomopsins, in which Tyr, not Phe, would need to be in- term dikaritins. We characterize PhomM as an S-adenosylmethionine– corporated into the phomopsin structure via a tRNA-dependent dependent α-N-methyltransferase that converts phomopsin A to pathway. Here we report our investigation of the biosynthetic path- an N,N-dimethylated congener (phomopsin E), and show that the way of phomopsins, which explains the paradoxical observations in methyltransferases involved in dikaritin biosynthesis have evolved the early labeling studies and unequivocally demonstrates that pho- differently and likely have broad substrate specificities. -

National Coverage Determination Procedure Code: 82977 Gamma Glutamyl Transferase CMS Policy Number: 190.32 Back to NCD List

National Coverage Determination Procedure Code: 82977 Gamma Glutamyl Transferase CMS Policy Number: 190.32 Back to NCD List Description: Gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) is an intracellular enzyme that appears in blood following leakage from cells. Renal tubules, liver, and pancreas contain high amounts, although the measurement of GGT in serum is almost always used for assessment of Hepatobiliary function. Unlike other enzymes which are found in heart, skeletal muscle, and intestinal mucosa as well as liver, the appearance of an elevated level of GGT in serum is almost always the result of liver disease or injury. It is specifically useful to differentiate elevated alkaline phosphatase levels when the source of the alkaline phosphatase increase (bone, liver, or placenta) is unclear. The combination of high alkaline phosphatase and a normal GGT does not, however, rule out liver disease completely. As well as being a very specific marker of Hepatobiliary function, GGT is also a very sensitive marker for hepatocellular damage. Abnormal concentrations typically appear before elevations of other liver enzymes or biliuria are evident. Obstruction of the biliary tract, viral infection (e.g., hepatitis, mononucleosis), metastatic cancer, exposure to hepatotoxins (e.g., organic solvents, drugs, alcohol), and use of drugs that induce microsomal enzymes in the liver (e.g., cimetidine, barbiturates, phenytoin, and carbamazepine) all can cause a moderate to marked increase in GGT serum concentration. In addition, some drugs can cause or exacerbate liver dysfunction (e.g., atorvastatin, troglitazone, and others as noted in FDA Contraindications and Warnings.) GGT is useful for diagnosis of liver disease or injury, exclusion of hepatobiliary involvement related to other diseases, and patient management during the resolution of existing disease or following injury. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Ron Caspi Peter Midford Peter D Karp An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Ingrid Keseler Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Gcf_001591825Cyc: Bacillus vietnamensis NBRC 101237 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. Anamika Kothari sn-glycerol phosphate phosphate pro phosphate phosphate phosphate thiamine molybdate D-xylose D-ribose glutathione 3-phosphate D-mannitol L-cystine L-djenkolate lanthionine α,β-trehalose phosphate phosphate [+ 3 more] α,α-trehalose predicted predicted ABC ABC FliY ThiT XylF RbsB RS10935 UgpC TreP PutP RS10200 PstB PstB RS10385 RS03335 RS20030 RS19075 transporter transporter of molybdate of phosphate α,β-trehalose 6-phosphate L-cystine D-xylose D-ribose sn-glycerol D-mannitol phosphate phosphate thiamine glutathione α α phosphate phosphate phosphate phosphate L-djenkolate 3-phosphate , -trehalose 6-phosphate pro 1-phosphate lanthionine molybdate phosphate [+ 3 more] Metabolic Regulator Amino Acid Degradation Amine and Polyamine Biosynthesis Macromolecule Modification tRNA-uridine 2-thiolation Degradation ATP biosynthesis a mature peptidoglycan a nascent β an N-terminal- -

Relating Metatranscriptomic Profiles to the Micropollutant

1 Relating Metatranscriptomic Profiles to the 2 Micropollutant Biotransformation Potential of 3 Complex Microbial Communities 4 5 Supporting Information 6 7 Stefan Achermann,1,2 Cresten B. Mansfeldt,1 Marcel Müller,1,3 David R. Johnson,1 Kathrin 8 Fenner*,1,2,4 9 1Eawag, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, 8600 Dübendorf, 10 Switzerland. 2Institute of Biogeochemistry and Pollutant Dynamics, ETH Zürich, 8092 11 Zürich, Switzerland. 3Institute of Atmospheric and Climate Science, ETH Zürich, 8092 12 Zürich, Switzerland. 4Department of Chemistry, University of Zürich, 8057 Zürich, 13 Switzerland. 14 *Corresponding author (email: [email protected] ) 15 S.A and C.B.M contributed equally to this work. 16 17 18 19 20 21 This supporting information (SI) is organized in 4 sections (S1-S4) with a total of 10 pages and 22 comprises 7 figures (Figure S1-S7) and 4 tables (Table S1-S4). 23 24 25 S1 26 S1 Data normalization 27 28 29 30 Figure S1. Relative fractions of gene transcripts originating from eukaryotes and bacteria. 31 32 33 Table S1. Relative standard deviation (RSD) for commonly used reference genes across all 34 samples (n=12). EC number mean fraction bacteria (%) RSD (%) RSD bacteria (%) RSD eukaryotes (%) 2.7.7.6 (RNAP) 80 16 6 nda 5.99.1.2 (DNA topoisomerase) 90 11 9 nda 5.99.1.3 (DNA gyrase) 92 16 10 nda 1.2.1.12 (GAPDH) 37 39 6 32 35 and indicates not determined. 36 37 38 39 S2 40 S2 Nitrile hydration 41 42 43 44 Figure S2: Pearson correlation coefficients r for rate constants of bromoxynil and acetamiprid with 45 gene transcripts of ECs describing nucleophilic reactions of water with nitriles. -

The Neurochemical Consequences of Aromatic L-Amino Acid Decarboxylase Deficiency

The neurochemical consequences of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency Submitted By: George Francis Gray Allen Department of Molecular Neuroscience UCL Institute of Neurology Queen Square, London Submitted November 2010 Funded by the AADC Research Trust, UK Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University College London (UCL) 1 I, George Allen confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed………………………………………………….Date…………………………… 2 Abstract Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) catalyses the conversion of 5- hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) and L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-dopa) to the neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine respectively. The inherited disorder AADC deficiency leads to a severe deficit of serotonin and dopamine as well as an accumulation of 5-HTP and L-dopa. This thesis investigated the potential role of 5- HTP/L-dopa accumulation in the pathogenesis of AADC deficiency. Treatment of human neuroblastoma cells with L-dopa or dopamine was found to increase intracellular levels of the antioxidant reduced glutathione (GSH). However inhibiting AADC prevented the GSH increase induced by L-dopa. Furthermore dopamine but not L-dopa, increased GSH release from human astrocytoma cells, which do not express AADC activity. GSH release is the first stage of GSH trafficking from astrocytes to neurons. This data indicates dopamine may play a role in controlling brain GSH levels and consequently antioxidant status. The inability of L-dopa to influence GSH concentrations in the absence of AADC or with AADC inhibited indicates GSH trafficking/metabolism may be compromised in AADC deficiency. -

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds.