Does Ownership Have an Effect on Accounting Quality?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Volksbank N.V. Annual Report 2020

2020 Annual Report REPORT OF THE BOARD GOVERNANCE RISK FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OTHER INFORMATION ADDITIONAL 2 de Volksbank N.V. Annual Report 2020 BETTER FOR EACH OTHER 4 OTHER INFORMATION 192 Key figures 6 Provisions regarding profit or loss appropriation 192 Foreword of the CEO 8 Independent auditor's report 194 1 STRATEGY AND PROGRESS 10 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 204 1.1 Economic developments 11 Definitions and abbreviations 204 1.2 Our Strategy 13 Disclaimer 210 1.3 Developments in our shared value ambition 15 1.4 Options for the future 18 1.5 Commercial developments 19 1.6 Financial results 20 1.7 Compliance and de Volksbank 24 1.8 Responsible tax policy 26 2 GOVERNANCE 28 2.1 Supervisory Board and Board of Directors 29 2.2 Report of the Supervisory Board 33 2.3 Banking Code 37 2.4 Dutch Corporate Governance Code 37 2.5 Legal structure of de Volksbank 38 2.6 Remuneration Report 38 3 RISK MANAGEMENT 44 3.1 Risk management structure 45 3.2 Strategic risks 52 3.3 Credit risk 54 3.4 Market risk 86 3.5 Non-financial risks 90 3.6 Liquidity management and funding strategy 94 3.7 Credit ratings 103 3.8 Capital management 104 3.9 Sustainability risk 115 3.10 Management statement 123 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 126 Consolidated financial statements 128 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 132 Company financial statements 178 Notes to the company financial statements 181 REPORT OF THE BOARD GOVERNANCE RISK FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OTHER INFORMATION ADDITIONAL de Volksbank N.V. Annual Report 2020 3 Presentation of information This 2020 Annual Report consists of: • The Report of the Board of Directors, comprising: This is our 2020 Annual Report. -

Annual Report 2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Content Profile 3 Statement from the board 5 Developments in the payment system 8 Activities Activities: Point-of-sale payment system 11 Activities: Online payments 14 Activities: Giro-based payments 18 Activities: Stability of Payment Chains 23 Activities: Security in the payment system 25 Appendices Appendix: Board and management 30 Appendix: Governance 31 Appendix: List of members 33 2 Annual Report 2016 Profile The payment system is the bloodstream of our economy, has many stakeholders and is of great social importance. Therefore it has the characteristics of a utility. The many parties involved, the many relevant laws and regulations, the requirements for high quality, new technological possibilities and the high number of transactions make the payment system complex and dynamic. Transparency, openness, accessibility and dialogue with all stakeholders are important prerequisites in the payment system. The Dutch Payments Association organizes the collective tasks in the Dutch payment system for its members. Our members provide payment services on the Dutch market: banks, payment institutions and electronic money institutions. The shared tasks for infrastructure, standards and common product features are assigned to the Payments Association. We aim for a socially efficient, secure, reliable and accessible payment system. To this end, we deploy activities that are of common interest to our members. We are committed, meaningful and interconnecting in everything we do, to unburden our members where and when possible. We engage representatives of end users in the payment system, including businesses and consumers. On behalf of our members, we are visibly involved and accessible and we are socially responsible. -

Stress Testing Governance, Risk Analytics and Instruments European Dr

VISIT OUR WEBSITE: www.flemingeurope.com “Linking the credit and liquidity risks” EXPERT ADVISORY BOARD nd ANNUAL DR. ANDREA BURGTORF Deutsche Bank, Germany, Head of Stress Testing HOP Governance, Risk Analytics and Instruments EUROPEAN S DR. LINda SLEDDENS Aegon Bank, Netherlands Senior Financial Risk Manager SUsaNNE HUGHES & WORK Lloyds Banking Group, UK STRess CE Senior Manager Stress Testing N PETER QUEll E R DZ Bank, Germany, Head of Portfolio Modelling E for Market and Credit Risk TESTING EXCLUSIVE SPEAKER PANEL CONF HEIKO HEssE for Banks IMF, USA, Economist, Monetary and Capital Markets Department 23-24 October 2013, Netherlands IaIN DE WEYMARN Bank of England, UK, Head of Banking System Division, Financial Stability Radisson Blu Hotel Amsterdam CAROLINE LIESEGANG EBA, UK, Senior Stress Testing Expert JEROME HENRY CONFERENCE & WORKSHOP ECB, Germany, Head of Financial Stability Assessment Division 2 Market conditions are in turmoil and a regulatory or risk management JAVIER VIllaR BURKE no one can be sure of the reaction. perspective. Moreover, you will be European Commission – DG ECFIN One of the ways of calming things able to benchmark your processes Statistical Officer down is reassuring the Financial and methodologies with your peers, environment about your ability regulators and gather diversity of ALEXANDER VasYUTOVIch to react promptly, safeguard your insights for your internal processes Promsvyazbank, Russia, Co-Chief Risk Officer clients’ interests and cope with improvement. Head of Financial and Retail Risk Management liquidity squeeze during stressed PETER QUEll periods. By incorporating stress To practice your stress testing DZ Bank, Germany, Head of Portfolio Modeling testing into your risk management techniques, we have prepared an for Market and Credit Risk methodologies, you are taking one intensive hands-on workshop called of the more important steps of doing Scenario Analysis in Stress Ewa RENZ so. -

List of PRA-Regulated Banks

LIST OF BANKS AS COMPILED BY THE BANK OF ENGLAND AS AT 1st February 2021 This document provides a list of Authorised Firms, it does not supersede the Financial Service Register which should be referred to as the most accurate and up to date source of information. Banks incorporated in the United Kingdom ABC International Bank Plc DB UK Bank Limited Access Bank UK Limited, The DF Capital Bank Limited Ahli United Bank (UK) PLC AIB Group (UK) Plc EFG Private Bank Limited Al Rayan Bank PLC Europe Arab Bank plc Aldermore Bank Plc Alliance Trust Savings Limited (Applied to Cancel) FBN Bank (UK) Ltd Allica Bank Ltd FCE Bank Plc Alpha Bank London Limited FCMB Bank (UK) Limited Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Atom Bank PLC Gatehouse Bank Plc Axis Bank UK Limited Ghana International Bank Plc GH Bank Limited Bank and Clients PLC Goldman Sachs International Bank Bank Leumi (UK) plc Guaranty Trust Bank (UK) Limited Bank Mandiri (Europe) Limited Gulf International Bank (UK) Limited Bank Of Baroda (UK) Limited Bank of Beirut (UK) Ltd Habib Bank Zurich Plc Bank of Ceylon (UK) Ltd Hampden & Co Plc Bank of China (UK) Ltd Hampshire Trust Bank Plc Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc Handelsbanken PLC Bank of London and The Middle East plc Havin Bank Ltd Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, The HBL Bank UK Limited Bank of Scotland plc HSBC Bank Plc Bank of the Philippine Islands (Europe) PLC HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited Bank Saderat Plc HSBC Trust Company (UK) Ltd Bank Sepah International Plc HSBC UK Bank Plc Barclays Bank Plc Barclays Bank UK PLC ICBC (London) plc BFC Bank Limited ICBC Standard Bank Plc Birmingham Bank Limited ICICI Bank UK Plc BMCE Bank International plc Investec Bank PLC British Arab Commercial Bank Plc Itau BBA International PLC Brown Shipley & Co Limited JN Bank UK Ltd C Hoare & Co J.P. -

"SOLIZE India Technologies Private Limited" 56553102 .FABRIC 34354648 @Fentures B.V

Erkende referenten / Recognised sponsors Arbeid Regulier en Kennismigranten / Regular labour and Highly skilled migrants Naam bedrijf/organisatie Inschrijfnummer KvK Name company/organisation Registration number Chamber of Commerce "@1" special projects payroll B.V. 70880565 "SOLIZE India Technologies Private Limited" 56553102 .FABRIC 34354648 @Fentures B.V. 82701695 01-10 Architecten B.V. 24257403 100 Grams B.V. 69299544 10X Genomics B.V. 68933223 12Connect B.V. 20122308 180 Amsterdam BV 34117849 1908 Acquisition B.V. 60844868 2 Getthere Holding B.V. 30225996 20Face B.V. 69220085 21 Markets B.V. 59575417 247TailorSteel B.V. 9163645 24sessions.com B.V. 64312100 2525 Ventures B.V. 63661438 2-B Energy Holding 8156456 2M Engineering Limited 17172882 30MHz B.V. 61677817 360KAS B.V. 66831148 365Werk Contracting B.V. 67524524 3D Hubs B.V. 57883424 3DUniversum B.V. 60891831 3esi Netherlands B.V. 71974210 3M Nederland B.V. 28020725 3P Project Services B.V. 20132450 4DotNet B.V. 4079637 4People Zuid B.V. 50131907 4PS Development B.V. 55280404 4WEB EU B.V. 59251778 50five B.V. 66605938 5CA B.V. 30277579 5Hands Metaal B.V. 56889143 72andSunny NL B.V. 34257945 83Design Inc. Europe Representative Office 66864844 A. Hak Drillcon B.V. 30276754 A.A.B. International B.V. 30148836 A.C.E. Ingenieurs en Adviesbureau, Werktuigbouw en Electrotechniek B.V. 17071306 A.M. Best (EU) Rating Services B.V. 71592717 A.M.P.C. Associated Medical Project Consultants B.V. 11023272 A.N.T. International B.V. 6089432 A.S. Watson (Health & Beauty Continental Europe) B.V. 31035585 A.T. Kearney B.V. -

Philanthropy Services by Dutch Banks: Creating Impact for Colleagues, Clients and Charities

Philanthropy services by Dutch banks: Creating impact for colleagues, clients and charities Philanthropy services by Dutch banks: Creating Impact for Colleagues, Clients and Charities Jacqueline Detiger (www.betergeven.nl) Joining forces for more impact In October 2015 four Dutch Charity Desks at banks offering philanthropy services to wealthy clients set up the FAFI network (the name derives from Philanthropy Advice by Financial Institutions). The aim of this cooperation is to meet regularly to share best practices, new perspectives and research results so as to improve knowledge and insights in philanthropy and to be able to expand the number of clients making use of philanthropy advice. Jacqueline Detiger ecent research in the Netherlands shows Banks provide this service because customers that wealthy individuals are looking for show a keen interest in it and it is part of these ways to give more strategically. Charity banks’ DNA. Guus Loomans of Rabobank states: desks of banks provide this service. In the “We have a long tradition of giving through our Rend, it is all about helping clients with their giving foundation and through our employee giving plan and to increase the number of clients investing in fund. Giving is in the DNA of our Cooperative charities: making the pie bigger for everyone! Bank. To be able to support our clients with philanthropy we started our Charity Management We even have a verb for joining forces so as to get Services eight years ago.” Andrew Mackay of positive results that are beneficial for everybody. Van Lanschot Charity Service remarks: “The client is asking us about giving and social investing. -

Triodos Bank Produces a Printed Version of the Annual Report

T¬B Annual Report 2016 Triodos Bank produces a printed version of the Annual Report. We do this because some of our stakeholders want to read the report in this format and because we are legally required to provide the Annual Report as a discrete, single document. However, we have chosen to put more energy into producing the Annual Report online. The online Annual Report includes content that is not in this document; from films highlighting the extraordinary work of the sustainable enterprises we finance and an interview with our CEO, to an extended chapter about Triodos Bank’s impact. We believe the online Annual Report provides a more complete picture of our performance and our aspirations for the future, and many more people choose to view it than read the report in print. It has also allowed us to reduce the number of printed copies of the report we produce each year. However you choose to read or view the Annual Report, we hope it provides you with a rich picture of Triodos Bank’s values-based mission, strategy and impact in the wider world. We appreciate your feedback, so please contact us via the ‘tell us what you think’ button on the homepage of the website. www.annual-report-triodos.com T¬B Triodos Bank is a co-founder of the Global Alliance for Banking on Values, a network of leading sustainable banks – visit www.gabv.org Important data for Triodos Bank’s shareholders and depository receipt holders. Annual general meeting 19 May 2017 Ex-dividend date 23 May 2017 Dividend payment date 26 May 2017 Annual Report 2016 Triodos Bank -

Download (471Kb)

Pas toe of leg uit “Een onderzoek naar de toepassing van de code banken en de code verzekeraars ten aanzien van beloningsbeleid.” M.M. Scheffer Leeghwaterstraat 99 6717CX Ede Studentnummer: 2232146 [email protected] Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Faculteit economie & bedrijfskunde Accountancy & Controlling Ernst & Young Audit services Amsterdam / Utrecht 1e Begeleider RuG: Prof. dr. J.A. van Manen RA 2e Begeleider RuG: dr. O.P.G. Bik RA Begeleider E&Y: drs. M.T. Lemans RA M.M. Scheffer Pas toe of leg uit Voorwoord Voor u ligt mijn scriptie ter afronding van mijn master accountancy & controlling aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. Ik heb het afgelopen jaar als zeer leerzaam en plezierig ervaren. Naast vakkennis heb ik mij in deze periode ook persoonlijk kunnen ontwikkelen. In deze scriptie staat corporate governance voor banken en verzekeraars centraal. Deze is vertaald in de code banken en de code verzekeraars. In deze scriptie is onderzoek gedaan naar de mate van naleving van de codes. Tevens is onderzocht in welke mate omvang van instellingen een rol speelt bij de naleving van de principes en tevens bij de kwaliteit van uitleg bij het niet toepassen van principes. Het onderzoek heb ik mogen uitvoeren bij mijn werkgever Ernst & Young te Utrecht. Graag wil ik mijn begeleider vanuit Ernst & Young, de heer drs. René Lémans RA, bedanken voor de begeleiding en hulp gedurende het gehele traject. Tevens wil ik de heren drs. Bob Leonards RA en mr. drs. Georges de Méris RA danken voor het meedenken en beantwoorden van mijn vakinhoudelijke vragen. Daarnaast wil ik graag mijn begeleiders vanuit de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, de heer Prof. -

Economic Expertise Regarding the Proposed Settlement Between Claimants’ Organizations and Ageas Sa/Nv

Confidential ECONOMIC EXPERTISE REGARDING THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT BETWEEN CLAIMANTS’ ORGANIZATIONS AND AGEAS SA/NV By ANALYSIS GROUP, INC. Marc Van Audenrode, Ph.D. Managing Principal 20 May 2016 Confidential TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... - 2 - A. Analysis Group ............................................................................................................................ - 2 - B. Mandate ........................................................................................................................................ - 3 - C. Materials Considered ................................................................................................................... - 3 - D. Disclaimer .................................................................................................................................... - 3 - E. Structure of the Report ................................................................................................................. - 4 - II. SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS .................................................................................................. - 4 - III. BACKGROUND ON THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT .................................... - 7 - IV. ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR ESTIMATING ECONOMIC LOSSES ........................... - 12 - A. Estimation of Potential Price Inflation ...................................................................................... -

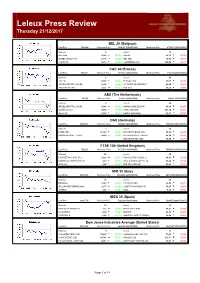

Leleux Press Review

Leleux Press Review Thursday 21/12/2017 BEL 20 (Belgium) Last Price 3994,68 Minimum Price 1046,07 (02/09/1992) Maximum Price 4759,01 (23/05/2007) Gainers 4 Losers 16 APERAM 43,85 +0,38% AGEAS 41,35 -0,79% ONTEX GROUP NV 27,75 +0,16% GBL (BE) 90,33 -0,79% COLRUYT 42,79 +0,03% COFINIMMO (BE) 110,00 -0,67% CAC 40 (France) Last Price 5352,77 Minimum Price 2693,21 (23/09/2011) Maximum Price 7347,94 (21/10/2009) Gainers 6 Losers 34 VALEO 62,09 +0,82% RENAULT SA 83,57 -0,98% ARCELORMITTAL SA (NL 26,98 +0,46% LAFARGEHOLCIM LTD (F 46,08 -0,96% VEOLIA ENV (FR) 21,27 +0,21% AXA (FR) 25,25 -0,88% AEX (The Netherlands) Last Price 547,38 Minimum Price 194,99 (09/03/2009) Maximum Price 806,41 (21/10/2009) Gainers 5 Losers 20 ARCELORMITTAL SA (NL 26,98 +0,46% KONINKLIJKE DSM NV 80,94 -0,93% GEMALTO N.V. 49,49 +0,29% ASML HOLDING 147,80 -0,90% RELX NV 19,24 +0,15% AHOLD DELHAIZE 18,33 -0,75% DAX (Germany) Last Price 13069,17 Minimum Price 7292,03 (26/11/2012) Maximum Price 13478,86 (03/11/2017) Gainers 2 Losers 28 LINDE (DE) 181,00 +0,58% DEUTSCHE BANK (DE) 16,64 -0,98% PROSIEBENSAT.1 NA O 29,00 +0,24% HEIDELBERGER ZEMENT 89,50 -0,92% DEUTSCHE TEL (DE) 15,00 -0,69% FTSE 100 (United Kingdom) Last Price 7525,22 Minimum Price 3277,50 (12/03/2003) Maximum Price 53548,10 (16/11/2009) Gainers 45 Losers 54 EASYJET PLC ORD 27 2 14,28 +0,97% ROYAL DUTCH SHELL A 24,05 -0,79% MARKS AND SPENCER GR 3,10 +0,97% ANGLO AMERICAN PLC O 14,88 -0,77% GKN (UK) 3,04 +0,91% SSE PLC ORD 50P 13,01 -0,77% MIB 30 (Italy) Last Price 22109,65 Minimum Price 12320,50 (24/07/2012) Maximum Price 48766,00 (05/04/2001) Gainers 13 Losers 26 BREMBO 12,80 +0,86% ATLANTIA SPA 26,45 -0,97% SALVATORE FERRAGAMO 21,75 +0,78% LUXOTTICA GROUP (IT) 50,95 -0,97% SAIPEM 3,63 +0,60% ENEL 5,28 -0,75% IBEX 35 (Spain) Last Price 10207,70 Minimum Price 5266,90 (10/10/2002) Maximum Price 15945,70 (08/11/2007) Gainers 15 Losers 19 BANCO DE SABADELL 1,72 +0,93% INDRA SISTEMAS 11,53 -0,98% CAIXABANK 4,00 +0,85% INDITEX 29,53 -0,92% IBERDROLA 6,58 +0,73% GAMESA CORP. -

A Nnual R Epo Rt 2 0 0 9 Fortis Bank Sa/Nv

Fortis Bank sa/nv - Annual Report 2009 Fortis Bank sa/nv Annual Report 2010 Introduction The 2010 Annual Report of Fortis Bank contains both the Consolidated and the Non-consolidated Financial Statements, preceded by the Report of the Board of directors, the Statement of the Board of directors and a section on Corporate Governance including the composition of the Board of directors. The audited Fortis Bank Consolidated Financial Statements 2010, with comparative figures for 2009, prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) as adopted by the European Union, are followed by the audited Non-consolidated Financial Statements 2010 of Fortis Bank SA/NV, prepared based on the rules laid down in the (Belgian) Royal Decree of 23 September 1992 on the annual accounts of credit institutions. All amounts in the tables of these Financial Statements are denominated in millions of euros, unless stated otherwise. Because figures have been rounded off, small differences with previously reported figures may occur. Certain reclassifications have been made with regard to the prior year’s Financial Statements in order to make them comparable to the presentation for the year under review. We refer to the note 8.k. “Comments on change of presentation” for more information on the representation of the Balance sheet as at 31 December 2009 and the Profit or loss account of the year 2009. Fortis Bank SA/NV is the legal name of the company and the commercial activities in Belgium are performed under the brand name BNP Paribas Fortis. Fortis Bank refers in the Consolidated Financial Statements to Fortis Bank SA/NV consolidated situation except if stated otherwise. -

Annual Report 2014 BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV 23/02/15 11:50

BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV Annual Report 2014 | Annual Report 2014 Report | Annual BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV Fortis Paribas BNP AR 2014 Cover.indd 6 23/02/15 11:50 Introduction The BNP Paribas Fortis Annual Report 2014 contains both the audited Consolidated and Non-consolidated Financial Statements, preceded by the Report of the Board of Directors, the Statement of the Board of Directors and a section on Corporate Governance including the composition of the Board of Directors. The audited BNP Paribas Fortis Consolidated Financial Statements 2014, with comparative figures for 2013, prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) as adopted by the European Union, are followed by the audited Non-consolidated Financial Statements 2014 of BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV, prepared on the basis of the rules laid down in the Belgian Royal Decree of 23 September 1992 on the annual accounts of credit institutions. All amounts in the tables of the Consolidated Financial All information contained in the BNP Paribas Fortis Annual Statements are denominated in millions of euros, unless Report 2014 relates to the BNP Paribas Fortis statutory stated otherwise. All amounts in the tables of the Non- Consolidated and Non-consolidated Financial Statements consolidated Financial Statements are denominated in and does not cover the contribution of BNP Paribas thousands of euros, unless stated otherwise. Because figures Fortis to the BNP Paribas Group consolidated results, have been rounded off, small discrepancies with previously which can be found on the BNP Paribas website: reported figures may appear. Certain reclassifications www.bnpparibas.com. have been made with regard to the prior year’s Financial Statements in order to make them comparable for the year The BNP Paribas Fortis Annual Report 2014 under review.