319 Chapter 9: Extraction (And Other Industries) in the Study Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Peak Trails and Cycle Routes

Things to See and Do The High Peak Trail by funded part Project The Countryside The Cromford and High Peak Railway was one of the first The White Peak is a spectacular landscape of open views railways in the world. It was built between 1825 and s www.derbyshire.gov.uk/buse characterised by the network of fields enclosed by dry stone Several Peak District 1830 to link the Peak Forest Canal at Whaley or 2608 608 0870 walls. North and south of Hartington the trails go down into villages have annual Bridge (north of Buxton) to the Traveline from timetables and services other updates, Check the deep valley of the Upper Dove and the steeper gorge at well dressings (a Cromford Canal – a distance of Hire. Cycle Waterhouses and tableau of flower- Beresford Dale. On the lower land are the towns and villages 33 miles. The railway itself was Hire Cycle Ashbourne to Leek and Derby links 108 Travel TM built from local stone in traditional style. based pictures designed like a canal. On the around the village flat sections the wagons were Hire. Cycle Hay Interesting Places wells). Ask at visitor pulled by horses. Large Manifold Track below Thor’s Cave Parsley and Hire Cycle Ashbourne to Buxton links 542 Bowers centres for dates. The Trails and White Peak cycle network have a rich industrial steam powered Centre. Hire Cycle Ashbourne and Hire Cycle Water heritage and railway history. beam engines in The Manifold Track Carsington to Wirksworth and Matlock links 411 Travel TM Look out for the sculpted benches along the Trails and the From Track to Trail And Further Afield ‘engine houses’ This was the Leek and Manifold Valley Light Railway. -

Proposed Revised Wards for Derbyshire Dales District Council

Proposed Revised Wards for Derbyshire Dales District Council October 2020 The ‘rules’ followed were; Max 34 Cllrs, Target 1806 electors per Cllr, use of existing parishes, wards should Total contain contiguous parishes, with retention of existing Cllr total 34 61392 Electorate 61392 Parish ward boundaries where possible. Electorate Ward Av per Ward Parishes 2026 Total Deviation Cllr Ashbourne North Ashbourne Belle Vue 1566 Ashbourne Parkside 1054 Ashbourne North expands to include adjacent village Offcote & Underwood 420 settlements, as is inevitable in the general process of Mappleton 125 ward reduction. Thorpe and Fenny Bentley are not Bradley 265 immediately adjacent but will have Ashbourne as their Thorpe 139 focus for shops & services. Their vicar lives in 2 Fenny Bentley 140 3709 97 1855 Ashbourne. Ashbourne South has been grossly under represented Ashbourne South Ashbourne Hilltop 2808 for several years. The two core parishes are too large Ashbourne St Oswald 2062 to be represented by 2 Cllrs so it must become 3 and Clifton & Compton 422 as a consequence there needs to be an incorporation of Osmaston 122 rural parishes into this new, large ward. All will look Yeldersley 167 to Ashbourne as their source of services. 3 Edlaston & Wyaston 190 5771 353 1924 Norbury Snelston 160 Yeaveley 249 Rodsley 91 This is an expanded ‘exisitng Norbury’ ward. Most Shirley 207 will be dependent on larger settlements for services. Norbury & Roston 241 The enlargement is consistent with the reduction in Marston Montgomery 391 wards from 39 to 34 Cubley 204 Boylestone 161 Hungry Bentley 51 Alkmonton 60 1 Somersal Herbert 71 1886 80 1886 Doveridge & Sudbury Doveridge 1598 This ward is too large for one Cllr but we can see no 1 Sudbury 350 1948 142 1948 simple solution. -

OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components

RECIPE GARUM OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components Grilled strawberries Red oxalis Veal head Pickled maple blossom Marmande D‘Antan tomatoes (8-10 cm Ø) Green juniper powder Tomato gelée Garum sauce Tomato/raspberry gel Lovage oil GRILLED MARMANDE TOMATO STRAWBER- D‘ANTAN GELÉE RIES TOMATOES Grill the red strawberries (not too Blanch and peel the tomatoes. 220 g clear tomato stock* sweet) and cut them into 3 mm Carefully cut them into 28 g slices 1,6 g Agar cubes, spread them out and chill so that the slices retain the shape 0,6 g Gelatine immediately. of the tomatoes. Place the slices 0,4 g of citrus next to each other on a deep Tomami (hearty) baking tray and cover with green White balsamic vinegar juniper oil heated to 100°C, leave to stand for at least 6 hours. Flavor the tomato stock* with tomami, vinegar, salt and sugar. Then bind with texturizers and pour on a plastic tray. Afterwards cut out circles with a ring (9 cm Ø). *(mix 1 kg of tomatoes with salt, put in a kitchen towel and place over a container to drain = stock) CHAUSSEESTRASSE 8 D-10115 BERLIN MITTE TEL. +49 30.24 62 87 60 MAIL: [email protected] TOMATO/ GARUM TROUT RASPBERRY SAUCE GARUM GEL 100 ml tomato stock* 1 L poultry stock from heavily 1 part trout (without head, fins 15 g fresh raspberries roasted poultry carcasses. and offal) Pork pancreas Sea salt Flavored with 20 g Kombu (5 % of trout weight) algae for for 30 minutes. Water (80 % of trout Mix everything together and 55 g Sauerkraut (with bacon) weight) Sea salt (10 % of strain through a fine sieve. -

Romans in Cumbria

View across the Solway from Bowness-on-Solway. Cumbria Photo Hadrian’s Wall Country boasts a spectacular ROMANS IN CUMBRIA coastline, stunning rolling countryside, vibrant cities and towns and a wealth of Roman forts, HADRIAN’S WALL AND THE museums and visitor attractions. COASTAL DEFENCES The sites detailed in this booklet are open to the public and are a great way to explore Hadrian’s Wall and the coastal frontier in Cumbria, and to learn how the arrival of the Romans changed life in this part of the Empire forever. Many sites are accessible by public transport, cycleways and footpaths making it the perfect place for an eco-tourism break. For places to stay, downloadable walks and cycle routes, or to find food fit for an Emperor go to: www.visithadrianswall.co.uk If you have enjoyed your visit to Hadrian’s Wall Country and want further information or would like to contribute towards the upkeep of this spectacular landscape, you can make a donation or become a ‘Friend of Hadrian’s Wall’. Go to www.visithadrianswall.co.uk for more information or text WALL22 £2/£5/£10 to 70070 e.g. WALL22 £5 to make a one-off donation. Published with support from DEFRA and RDPE. Information correct at time Produced by Anna Gray (www.annagray.co.uk) of going to press (2013). Designed by Andrew Lathwell (www.lathwell.com) The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in Rural Areas visithadrianswall.co.uk Hadrian’s Wall and the Coastal Defences Hadrian’s Wall is the most important Emperor in AD 117. -

200 Bc - Ad 400)

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 171-191 P. ARNAUD 171 BEIRUT: COMMERCE AND TRADE (200 BC - AD 400) PASCAL ARNAUD We know little of Beirut's commerce and trade, and shall probably continue to know little about this matter, despite a lecture given by Mrs Nada Kellas in 19961. In fact, the history of Commerce and Trade relies mainly on both ar- chaeological and epigraphical evidence. As far as archaeological evidence is concerned, one must remember that only artefacts strongly linked with ceram- ics, i.e. vases themselves and any items, carried in amphoras, (predominantly, but not solely, liquids, can give information about the geographical origin, date and nature of such products. The huge quantities of materials brought to the light by recent excavations in Beirut should, one day, provide us with new evi- dence about importations of such products in Beirut, but we will await the complete study of this material, which, until today by no means provided glo- bal statistics valid at the whole town scale. The evidence already published still allows nothing more than mere subjective impressions about the origins of the material. I shall try nevertheless to rely on such impressions about that ma- terial, given that we lack statistics, and that it is impossible to infer from any isolated sherd the existence of permanent trade-routes and commercial flows. The results of such an inquiry would be, at present, worth little if not con- fronted with other evidence. On the other hand, it should be of great interest to identify specific Berytan productions among the finds from other sites in order to map the diffusion area of items produced in Beirut and the surrounding territory. -

Land at Blacksmith's Arms

Land off North Road, Glossop Education Impact Assessment Report v1-4 (Initial Research Feedback) for Gladman Developments 12th June 2013 Report by Oliver Nicholson EPDS Consultants Conifers House Blounts Court Road Peppard Common Henley-on-Thames RG9 5HB 0118 978 0091 www.epds-consultants.co.uk 1. Introduction 1.1.1. EPDS Consultants has been asked to consider the proposed development for its likely impact on schools in the local area. 1.2. Report Purpose & Scope 1.2.1. The purpose of this report is to act as a principle point of reference for future discussions with the relevant local authority to assist in the negotiation of potential education-specific Section 106 agreements pertaining to this site. This initial report includes an analysis of the development with regards to its likely impact on local primary and secondary school places. 1.3. Intended Audience 1.3.1. The intended audience is the client, Gladman Developments, and may be shared with other interested parties, such as the local authority(ies) and schools in the area local to the proposed development. 1.4. Research Sources 1.4.1. The contents of this initial report are based on publicly available information, including relevant data from central government and the local authority. 1.5. Further Research & Analysis 1.5.1. Further research may be conducted after this initial report, if required by the client, to include a deeper analysis of the local position regarding education provision. This activity may include negotiation with the relevant local authority and the possible submission of Freedom of Information requests if required. -

Peak District National Park Visitor Survey 2005

PEAK DISTRICT NATIONAL PARK VISITOR SURVEY 2005 Performance Review and Research Service www.peakdistrict.gov.uk Peak District National Park Authority Visitor Survey 2005 Member of the Association of National Park Authorities (ANPA) Aldern House Baslow Road Bakewell Derbyshire DE45 1AE Tel: (01629) 816 200 Text: (01629) 816 319 Fax: (01629) 816 310 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.peakdistrict.gov.uk Your comments and views on this Report are welcomed. Comments and enquiries can be directed to Sonia Davies, Research Officer on 01629 816 242. This report is accessible from our website, located under ‘publications’. We are happy to provide this information in alternative formats on request where reasonable. ii Acknowledgements Grateful thanks to Chatsworth House Estate for allowing us to survey within their grounds; Moors for the Future Project for their contribution towards this survey; and all the casual staff, rangers and office based staff in the Peak District National Park Authority who have helped towards the collection and collation of the information used for this report. iii Contents Page 1. Introduction 1.1 The Peak District National Park 1 1.2 Background to the survey 1 2. Methodology 2.1 Background to methodology 2 2.2 Location 2 2.3 Dates 3 2.4 Logistics 3 3. Results: 3.1 Number of people 4 3.2 Response rate and confidence limits 4 3.3 Age 7 3.4 Gender 8 3.5 Ethnicity 9 3.6 Economic Activity 11 3.7 Mobility 13 3.8 Group Size 14 3.9 Group Type 14 3.10 Groups with children 16 3.11 Groups with disability 17 3.12 -

Roman Lead Sealings

Roman Lead Sealings VOLUME I MICHAEL CHARLES WILLIAM STILL SUBMITTED FOR TIlE DEGREE OF PILD. SEPTEMBER 1995 UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY (L n") '3 1. ABSTRACT This thesis is based on a catalogue of c. 1800 records, covering over 2000 examples of Roman lead sealings, many previously unpublished. The catalogue is provided with indices of inscriptions and of anepigraphic designs, and subsidiary indices of places, military units, private individuals and emperors mentioned on the scalings. The main part of the thesis commences with a history of the use of lead sealings outside of the Roman period, which is followed by a new typology (the first since c.1900) which puts special emphasis on the use of form as a guide to dating. The next group of chapters examine the evidence for use of the different categories of scalings, i.e. Imperial, Official, Taxation, Provincial, Civic, Military and Miscellaneous. This includes evidence from impressions, form, texture of reverse, association with findspot and any literary references which may help. The next chapter compares distances travelled by similar scalings and looks at the widespread distribution of identical scalings of which the origin is unknown. The first statistical chapter covers imperial sealings. These can be assigned to certain periods and can thus be subjected to the type of analysis usually reserved for coins. The second statistical chapter looks at the division of categories of scalings within each province. The scalings in each category within each province are calculated as percentages of the provincial total and are then compared with an adjusted percentage for that category in the whole of the empire. -

Roman Forts and Fortresses Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary

Roman Forts and Fortresses Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary Historic England’s Introductions to Heritage Assets (IHAs) are accessible, authoritative, illustrated summaries of what we know about specific types of archaeological site, building, landscape or marine asset. Typically they deal with subjects which have previously lacked such a published summary, either because the literature is dauntingly voluminous, or alternatively where little has been written. Most often it is the latter, and many IHAs bring understanding of site or building types which are neglected or little understood. This IHA provides an introduction to Roman forts and fortresses (permanent or semi- permanent bases of Roman troops). These installations were a very important feature of the Roman period in Britain, as the British provinces were some of the most heavily militarised in the Roman Empire. Descriptions of the asset type and its development as well as its associations and a brief chronology are included. A list of in-depth sources on the topic is suggested for further reading. This document has been prepared by Pete Wilson and edited by Joe Flatman, Pete Herring and Dave Went. It is one of a series of 41 documents. This edition published by Historic England October 2018. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Please refer to this document as: Historic England 2018 Roman Forts and Fortresses: Introductions to Heritage Assets. Swindon. Historic England. HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/selection-criteria/scheduling-selection/ihas-archaeology/ Front cover: Whitley Castle auxiliary fort, Northumberland (near Alston in Cumbria), from the east in 2007. Introduction Roman forts and fortresses (as opposed to camps) were the permanent or semi- permanent bases of Roman troops. -

The Journal of Roman Studies Volume Xxxiii 1943 Parts I and Ii

THE JOURNAL OF ROMAN STUDIES VOLUME XXXIII 1943 PARTS I AND II CONTENTS M. P. Charlesworth, Pietas and Victoria: the Emperor and the Citizen W. W. Buckland, Gaius i, 166 ' Tutela parentis manumissoris ' Charles Green, Glevum and the Second Legion, ii Norman H. Baynes, The Decline of the Roman Power in Western Europe. Some Modern Explanations. R. P. Wright, The Whitley Castle Altar to Apollo J. M. R. Cormack, High Priests and Macedoniarchs from Beroea I. A. Richmond, Recent Discoveries in Roman Britain from the Air and in the Field Fritz Schulz, Roman Registers of Birth and Birth Certificates, ii Gervase Mathew, The Character of the Gallienic Renaissance Roman Britain in 1942 REVIEWS AND DISCUSSIONS G. Tseretheli, A Bilingual Inscription from Armazi near Mcfyeta in Georgia (by Marcus N. Tod) P. W. Duff, Personality in Roman Private Law, i (by David Daube) H. J. Haskell, This was Cicero : Modern Politics in a Roman Toga (by Hugh Last) E. M. Dohan, Italic Tomb-Groups in the University Museum, Philadelphia (by Paul Jacobsthal) REVIEWS AND NOTICES OF PUBLICATIONS REVIEWS Emanuele Ciaceri, Le origini di Roma: la Donald Atkinson, Report on Excavations at Monarchia e la prima fase dell' Eta repubbli- Wroxeter {the Roman city of Viroconium) in cana (dal Sec. VIII alia meta del Sec. V A.C.) the County of Salop C. E. Smith, Tiberius and the Roman Empire E. Lobel, C. H. Roberts, and E. P. Wegener, John Day, An Economic History of Athens under The Oxyrhynchus Papyri, Part xviii Roman Domination Transactions and Proceedings of the American K. Lehmann-Hartleben and E. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

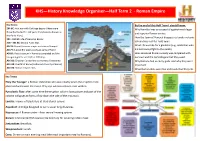

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

Brassington Conservation Area Appraisal

Brassington Conservation Area Appraisal January 2008 BRASSINGTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL page Summary 1 1. Brassington in Context 2 2 Origins & Development 3 • Topography & Geology • Historic Development 3. Archaeological Significance 13 4. Architectural and Historic Quality 15 • Key Buildings • Building Materials & Architectural Details 5. Setting of the Conservation Area 44 6. Landscape Appraisal 47 7. Analysis of Character 60 8. Negative Factors 71 9. Neutral Factors 75 10. Justification for Boundary 76 • Recommendations for Amendment 11. Conservation Policies & Legislation 78 • National Planning Guidance • Regional Planning Guidance • Local Planning Guidance Appendix 1 Statutory Designations (Listed Buildings) Sections 1-5 & 7-10 prepared by Mel Morris Conservation , Ipstones, Staffordshire ST10 2LY on behalf of Derbyshire Dales District Council All photographs within these sections have been taken by Mel Morris Conservation © September 2007 i BRASSINGTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL List of Figures Fig. 1 Aerial Photograph Fig. 2 Brassington in the Derbyshire Dales Fig. 3 Brassington Conservation Area Fig. 4 Brassington - Enclosure Map (inset of town plan) 1808 Fig. 5 First edition Ordnance Survey map of 1880 Fig. 6 Building Chronology Fig. 7 Historic Landscape Setting Fig. 8 Planning Designations: Trees & Woodlands Fig. 9 Landscape Appraisal Zones Fig. 10 Relationship of Structures & Spaces Fig. 11 Conservation Area Boundary - proposed areas for extension & exclusion Fig. 12 Conservation Area Boundary Approved January 2008 List of Historic Illustrations & Acknowledgements Pl. 1 Extract from aerial photograph (1974) showing lead mining landscape (© Derbyshire County Council 2006) Pl. 2 Late 19th century view of Well Street, Brassington (reproduced by kind permission of Tony Holmes) Pl. 3 Extract from Sanderson’s map of 20 Miles round Mansfield 1835 (by kind permission of Local Studies Library, Derbyshire County Council) Pl.