2004A IE Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balsam Woolly Adelgid

A New Utah Forest Insect This fact sheet Pest: Balsam Woolly Adelgid introduces an invasive forest pest, the balsam By: Darren McAvoy, Extension Forestry Assistant Professor, woolly adelgid, and Diane Alston, Professor & Extension Entomologist, discusses its impacts on Ryan Davis, Arthropod Diagnostician, Utah forests, life cycle Megan Dettenmaier, Extension Forestry Educator traits, identifying characteristics, control Introduction methods, and steps that In 2017, the USDA Forest Service’s Forest Health Protection (FHP) group in Utah partners are taking Ogden, Utah detected and confirmed the presence of a new invasive forest to combat this pest. pest in Utah called the balsam woolly adelgid (BWA). First noticed in the mountains above Farmington Canyon and near Powder Mountain Resort, it has Dieback and decline of subalpine fir due to attack by balsam woolly adelgid. Photo credit: Darren McAvoy. 2017, forest health professionals visited Farmington Canyon on the ground and found branch node swelling (a node is where branch structures come together) and old deposits of woolly material on mature subalpine fir trees. Suspected to have originated in the Caucasus Mountains between Europe and Asia, BWA was first detected in North America in Maine, in 1908, and in California about 20 years later. It was detected in Idaho near Coeur d’Alene in 1983 and has since spread across northern Idaho. It is believed that separate invasions of subspecies or races of BWA may differentially impact tree host species. Dieback of subalpine fir, pacific silver (Abies amabilis) and grand fir (A. grandis) in Idaho is widespread. In the western Payette National Forest, north of Boise, an estimated 70% of subalpine fir trees are dead and falling down. -

The Salamanders of Tennessee

Salamanders of Tennessee: modified from Lisa Powers tnwildlife.org Follow links to Nongame The Salamanders of Tennessee Photo by John White Salamanders are the group of tailed, vertebrate animals that along with frogs and caecilians make up the class Amphibia. Salamanders are ectothermic (cold-blooded), have smooth glandular skin, lack claws and must have a moist environment in which to live. 1 Amphibian Declines Worldwide, over 200 amphibian species have experienced recent population declines. Scientists have reports of 32 species First discovered in 1967, the golden extinctions, toad, Bufo periglenes, was last seen mainly species of in 1987. frogs. Much attention has been given to the Anurans (frogs) in recent years, however salamander populations have been poorly monitored. Photo by Henk Wallays Fire Salamander - Salamandra salamandra terrestris 2 Why The Concern For Salamanders in Tennessee? Their key role and high densities in many forests The stability in their counts and populations Their vulnerability to air and water pollution Their sensitivity as a measure of change The threatened and endangered status of several species Their inherent beauty and appeal as a creature to study and conserve. *Possible Factors Influencing Declines Around the World Climate Change Habitat Modification Habitat Fragmentation Introduced Species UV-B Radiation Chemical Contaminants Disease Trade in Amphibians as Pets *Often declines are caused by a combination of factors and do not have a single cause. Major Causes for Declines in Tennessee Habitat Modification -The destruction of natural habitats is undoubtedly the biggest threat facing amphibians in Tennessee. Housing, shopping center, industrial and highway construction are all increasing throughout the state and consequently decreasing the amount of available habitat for amphibians. -

Biological Control of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Biological Control BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF HEMLOCK WOOLLY ADELGID TECHNICALCONTRIBUTORS: RICHARD REARDON FOREST HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ENTERPRISE TEAM, USDA FOREST SERVICE, MORGANTOWN, WEST VIRGINIA BRAD ONKEN FOREST HEALTH PROTECTION, USDA FOREST SERVICE, MORGANTOWN, WEST VIRGINIA AUTHORS: CAROLE CHEAH THE CONNECTICUT AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION MIKE MONTGOMERY NORTHEASTERN RESEARCH STATION SCOTT SALEM VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AND STATE UNIVERSITY BRUCE PARKER, MARGARET SKINNER, SCOTT COSTA UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT FHTET-2004-04 U.S. Department Forest of Agriculture Service FHTET he Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team (FHTET) was created in T1995 by the Deputy Chief for State and Private Forestry, USDA, Forest Service, to develop and deliver technologies to protect and improve the health of American forests. This book was published by FHTET as part of the technology transfer series. http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/ On the cover Clockwise from top left: adult coccinellids Sasajiscymnus tsugae, Symnus ningshanensis, and Scymnus sinuanodulus, adult derodontid Laricobius nigrinus, hemlock woolly adelgid infected with Verticillium lecanii. For copies of this publication, please contact: Brad Onken Richard Reardon Forest Health Protection Forest Health Technology Enterprise Morgantown, West Virginia Team Morgantown, West Virginia 304-285-1546 304-285-1566 [email protected] [email protected] All images in the publication are available online at http://www.forestryimages.org and http://www.invasive.org Reference numbers for the digital files appear in the figure captions in this publication. The entire publication is available online at http://www.bugwood.org and http://www.fs.fed.us/na/morgantown/fhp/hwa. The U.S. -

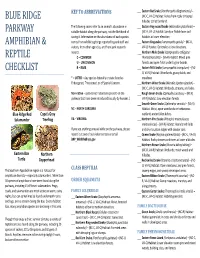

Amphibian and Reptile Checklist

KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS ___ Eastern Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) – BLUE RIDGE (NC‐C, VA‐C) Habitat: Varies from rocky timbered hillsides to flat farmland. The following codes refer to an animal’s abundance in ___ Eastern Hog‐nosed Snake (Heterodon platirhinos) – PARKWAY suitable habitat along the parkway, not the likelihood of (NC‐R, VA‐U) Habitat: Sandy or friable loam soil seeing it. Information on the abundance of each species habitats at lower elevation. AMPHIBIAN & comes from wildlife sightings reported by park staff and ___ Eastern Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula) – (NC‐U, visitors, from other agencies, and from park research VA‐U) Habitat: Generalist at low elevations. reports. ___ Northern Mole Snake (Lampropeltis calligaster REPTILE C – COMMON rhombomaculata) – (VA‐R) Habitat: Mixed pine U – UNCOMMON forests and open fields under logs or boards. CHECKLIST R – RARE ___ Eastern Milk Snake (Lampropeltis triangulum) – (NC‐ U, VA‐U) Habitat: Woodlands, grassy balds, and * – LISTED – Any species federally or state listed as meadows. Endangered, Threatened, or of Special Concern. ___ Northern Water Snake (Nerodia sipedon sipedon) – (NC‐C, VA‐C) Habitat: Wetlands, streams, and lakes. Non‐native – species not historically present on the ___ Rough Green Snake (Opheodrys aestivus) – (NC‐R, parkway that have been introduced (usually by humans.) VA‐R) Habitat: Low elevation forests. ___ Smooth Green Snake (Opheodrys vernalis) – (VA‐R) NC – NORTH CAROLINA Habitat: Moist, open woodlands or herbaceous Blue Ridge Red Cope's Gray wetlands under fallen debris. Salamander Treefrog VA – VIRGINIA ___ Northern Pine Snake (Pituophis melanoleucus melanoleucus) – (VA‐R) Habitat: Abandoned fields If you see anything unusual while on the parkway, please and dry mountain ridges with sandier soils. -

Biodiversity from Caves and Other Subterranean Habitats of Georgia, USA

Kirk S. Zigler, Matthew L. Niemiller, Charles D.R. Stephen, Breanne N. Ayala, Marc A. Milne, Nicholas S. Gladstone, Annette S. Engel, John B. Jensen, Carlos D. Camp, James C. Ozier, and Alan Cressler. Biodiversity from caves and other subterranean habitats of Georgia, USA. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 82, no. 2, p. 125-167. DOI:10.4311/2019LSC0125 BIODIVERSITY FROM CAVES AND OTHER SUBTERRANEAN HABITATS OF GEORGIA, USA Kirk S. Zigler1C, Matthew L. Niemiller2, Charles D.R. Stephen3, Breanne N. Ayala1, Marc A. Milne4, Nicholas S. Gladstone5, Annette S. Engel6, John B. Jensen7, Carlos D. Camp8, James C. Ozier9, and Alan Cressler10 Abstract We provide an annotated checklist of species recorded from caves and other subterranean habitats in the state of Georgia, USA. We report 281 species (228 invertebrates and 53 vertebrates), including 51 troglobionts (cave-obligate species), from more than 150 sites (caves, springs, and wells). Endemism is high; of the troglobionts, 17 (33 % of those known from the state) are endemic to Georgia and seven (14 %) are known from a single cave. We identified three biogeographic clusters of troglobionts. Two clusters are located in the northwestern part of the state, west of Lookout Mountain in Lookout Valley and east of Lookout Mountain in the Valley and Ridge. In addition, there is a group of tro- globionts found only in the southwestern corner of the state and associated with the Upper Floridan Aquifer. At least two dozen potentially undescribed species have been collected from caves; clarifying the taxonomic status of these organisms would improve our understanding of cave biodiversity in the state. -

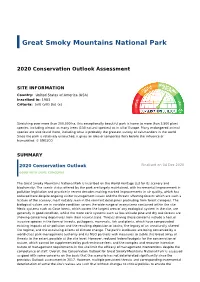

2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Great Smoky Mountains National Park - 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment Great Smoky Mountains National Park 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment SITE INFORMATION Country: United States of America (USA) Inscribed in: 1983 Criteria: (vii) (viii) (ix) (x) Stretching over more than 200,000 ha, this exceptionally beautiful park is home to more than 3,500 plant species, including almost as many trees (130 natural species) as in all of Europe. Many endangered animal species are also found there, including what is probably the greatest variety of salamanders in the world. Since the park is relatively untouched, it gives an idea of temperate flora before the influence of humankind. © UNESCO SUMMARY 2020 Conservation Outlook Finalised on 04 Dec 2020 GOOD WITH SOME CONCERNS The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is inscribed on the World Heritage List for its scenery and biodiversity. The scenic vistas offered by the park are largely maintained, with incremental improvement in pollution legislation and practice in recent decades making marked improvements in air quality, which has reduced haze despite ongoing visitor management issues and the threats affecting forests which are such a feature of the scenery, most notably seen in the remnant dead pines protruding from forest canopies. The biological values are in variable condition across the wide range of ecosystems contained within the site. Mesic systems such as Cove forest, which covers the largest area of any ecological system in the site, are generally in good condition, whilst the more xeric systems such as low-altitude pine and dry oak forests are showing concerning departures from their natural state. -

Chapter 16. Evaluating Host Range of Laricobius Nigrinus for Introduction Into the Eastern United States for Biological Control of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

ASSESSING HOST RANGES OF PARASITOIDS AND PREDATORS _________________________________ CHAPTER 16. EVALUATING HOST RANGE OF LARICOBIUS NIGRINUS FOR INTRODUCTION INTO THE EASTERN UNITED STATES FOR BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF HEMLOCK WOOLLY ADELGID G. Zilahi-Balogh Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, Harrow, Ontario, Canada [email protected] HEMLOCK WOOLLY ADELGID IN NORTH AMERICA The hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), Adelges tsugae Annand (Homoptera: Adelgidae), is a serious threat to hemlock landscape and forest stands in the eastern United States (McClure, 1996). Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis [L.] Carr.) and Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana Engelm.) are very susceptible to HWA attack, and infested trees have died in as little as four years (McClure, 1991). DISTRIBUTION OF HWA HWA is believed to have originated in Asia (McClure, 1987), and was first observed in North America in the Pacific Northwest in the early 1920s, where Annand (1924) described it from specimens collected on western hemlock, Tsuga heterophylla (Raf.) Sargent, in Oregon. An earlier description in 1922 identified the species as Chermes funitectus Dreyfus, also from west- ern hemlock in Vancouver, British Columbia (Annand, 1928). Annand (1928) reported that the two species were the same. HWA is exotic to eastern North America (McClure, 1987). First collected in the eastern United States in Virginia in 1951 in an ornamental setting (Stoetzel, 2002), it has spread to forests where it currently occurs in parts of 16 states along the eastern seaboard from North Carolina to New England (USDA FS, 2004). The main front of the HWA infestation is ad- vancing at approximately 25 km per year (McClure, 2001). There are nine recognized species of hemlock (Farjon, 1990). -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Facsheet Dec 2018

Dr. Carole Cheah Valley Laboratory The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 153 Cook Hill Road, P. O. Box 248 Windsor, CT 06095 Phone: (860) 683-4980 Fax: (860) 683-4987 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA) and Other Factors Impacting Eastern Hemlock Introduction and Overview Adelgids are small conifer-feeding insects, related to aphids, belonging to the Suborder Homoptera (1). Hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae Annand, (HWA), feeds specifically on hemlock species and was first described from samples originally from Oregon by P. N. Annand in California in 1924 (2). In North America, native Eastern hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carriere and Carolina hemlock, Tsuga caroliniana Engelmann are very susceptible to HWA attack (3). Eastern hemlock is the seventh most common tree species in Connecticut and the second most abundant conifer after eastern white pine (4). In the eastern United States, this non- native insect pest was initially reported at a private estate in Richmond, Virginia in the early 1950s (5). The hemlock woolly adelgid in eastern US originated from southern Honshu island, Japan (6) and infestations have since spread widely to attack eastern hemlock and Carolina hemlock in 20 eastern states, from the southern Appalachians in the Carolinas and Georgia, through the Mid-Atlantic States, westwards to Ohio and Michigan and northwards to northern New England (7). Most recently, HWA was found in southern Nova Scotia in Canada in 2017 (8). In Connecticut, HWA was first reported to the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station in New Haven in 1985 and by 1997, was found throughout the state, in all 169 Connecticut towns (7). -

Balsam Woolly Adelgid Management

Forest Health Protection and March 2010 State Forestry Partners 7.6 WEB July 2010 Management Guide for R. Ladd Livingston Balsam Woolly Adelgid Lee Pederson, US Forest Service Adelges piceae (Ratzeburg) Topics Subalpine fir is most susceptible. Grand fir is most resistant to damage. Overview 1 All true firs may be hosts. Life History 2 Natural Control 2 This European invader was first found in northern Idaho in 1983. It has expanded south to the Silvicultural 3 Alternatives Sawtooth National Forest, killing substantial numbers of subalpine fir. Chemical Control 3 Recognizing 4 adelgid damage Damage depends on population density Other Reading 4 Balsam woolly adelgid was around the buds and branch nodes. Field Guide discovered in northern Idaho in All sizes of trees are attacked. 1983 feeding predominantly on but the infestations may be Management Guide Index subalpine fir and to a less extent, concentrated on the stems or in the grand fir. Since that time, it has crowns. Stem-attacked trees can die been found from the Canadian after only 2-3 years of heavy border to as for south as the infestation and without any apparent Sawtooth National Forest in Idaho. gouting. Key Points It has caused extensive mortality of In the crowns, gouts occur on It is a non- subalpine fir, especially in low- the fastest growing parts of the tree, native species elevation drainage bottoms. and on trees that have been lightly that has only Nymphs feed on the bark of stems, infested for a long time. These trees been known in branches, and twigs, and at the decline slowly, growth is reduced, Idaho since base of new shoots and buds, but and the dead and dying upper stem is 1983. -

Terrestrial Ecosystems 3 Chapter 1

TERRESTRIAL Chapter 1: Terrestrial Ecosystems 3 Chapter 1: What are the history, Terrestrial status, and projected future of terrestrial wildlife habitat types and Ecosystems species in the South? Margaret Katherine Trani (Griep) Southern Region, USDA Forest Service ■ Since presettlement, there have insect infestation, advanced age, Key Findings been significant losses of community climatic processes, and distur- biodiversity in the South (Noss and bance influence mast yields. ■ There are 132 terrestrial vertebrate others 1995). Fourteen communities ■ The ranges of many species species that are considered to be are critically endangered (greater cross both public and private of conservation concern in the South than 98-percent decline), 25 are land ownerships. The numbers of by State Natural Heritage agencies. endangered (85- to 98-percent imperiled and endangered species Of the species that warrant conser- decline), and 11 are threatened inhabiting private land indicate its vation focus, 3 percent are classed (70- to 84-percent decline). Common critical importance for conservation. factors contributing to the loss of as critically imperiled, 3 percent ■ The significance of land owner- as imperiled, and 6 percent as these communities include urban development, fire suppression, ship in the South for the provision vulnerable. Eighty-six percent of species habitat cannot be of terrestrial vertebrate species exotic species invasion, and recreational activity. overstated. Each major landowner are designated as relatively secure. has an important role to play in ■ The remaining 2 percent are either The term “fragmentation” the conservation of species and known or presumed to be extinct, references the insularization of their habitats. or have questionable status. habitat on a landscape. -

Balsam Woolly Adelgid (Adelges Piceae)

Balsam Woolly Adelgid (Adelges piceae) Why we care: Balsam woolly adelgid (BWA) is a sap-feeding insect that attacks true fir trees, including balsam fir and Fraser fir. Repeated attacks weaken trees, cause twig gouting, kill branches and, over the course of several years, cause trees to die. What is at risk? There are nearly 1.9 billion balsam fir trees in Michigan’s forests. And, as the third- largest Christmas tree-growing state in the country, Michigan produces nearly 13.5 million fir trees each year, grown on over 11,500 acres. True fir trees, including forest, landscape and Christmas trees, are susceptible. Small (less than 1/32 nd of an inch) purplish-black adults form white, waxy “wool” covering twigs, branches and stems of infested trees (see photo). Smaller, amber-colored crawlers hatch in mid- summer. This is the mobile stage, when risk of movement by wind and wildlife is highest. The threat: BWA could be introduced into Michigan in a number of ways, including infested nursery stock, firewood, logs and vehicles. Once here, wind, birds and animals can carry this insect for miles. What could happen in Michigan? Accidentally introduced to southeastern Canada from Europe around 1900, BWA is already established in, and continues to threaten, fir trees in the Pacific Northwest, several northeastern states and the Central Atlantic states. In Great Smoky Mountains National Park, for example, 95% of Fraser firs have been killed by BWA. What you can do? If you notice white, waxy material on twigs, branches or stems, or twig gouting on fir trees, do not move them! Take photos, note the location and report it! Balsam woolly adelgid-induced twig gouting on Fraser fir Balsam woolly adelgid -infested balsam fir twig William M.