An Original Composition for Chorus Missa Brevis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bernsteincelebrating More Sides of the Story

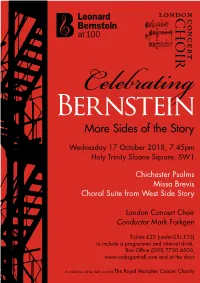

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018, 7.45pm Holy Trinity Sloane Square, SW1 Chichester Psalms Missa Brevis Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Conductor Mark Forkgen Tickets £25 (under-25s £15) to include a programme and interval drink. Box Office (020) 7730 4500, www.cadoganhall.com and at the door A collection will be held in aid of The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity One of the most talented and successful musicians in American history, Leonard Bernstein was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, educator and humanitarian. His versatility as a composer is brilliantly illustrated in this concert to celebrate the centenary of his birth. The Dean of Chichester commissioned the Psalms for the 1965 Southern Cathedrals Festival with the request that the music should contain ‘a hint of West Side Story.’ Bernstein himself described the piece as ‘forthright, songful, rhythmic, youthful.’ Performed in Hebrew and drawing on jazz rhythms and harmonies, the Psalms Music Director: include an exuberant setting of ‘O be joyful In the Lord all Mark Forkgen ye lands’ (Psalm 100) and a gentle Psalm 23, ‘The Lord is my shepherd’, as well as some menacing material cut Nathan Mercieca from the score of the musical. countertenor In 1988 Bernstein revisited the incidental music in Richard Pearce medieval style that he had composed in 1955 for organ The Lark, Anouilh’s play about Joan of Arc, and developed it into the vibrant Missa Brevis for unaccompanied choir, countertenor soloist and percussion. Anneke Hodnett harp After three contrasting solo songs, the concert is rounded off with a selection of favourite numbers from Sacha Johnson and West Side Story, including Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, Alistair Marshallsay America and Somewhere. -

LCOM182 Lent & Eastertide

LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC Lent, Holy Week, and Eastertide 2018 GRACE CATHEDRAL 2 LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC GRACE CATHEDRAL SAN FRANCISCO LENT, HOLY WEEK, AND EASTERTIDE 2018 11 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LÆTARE Introit: Psalm 32:1-6 – Samuel Wesley Service: Collegium Regale – Herbert Howells Psalm 107 – Thomas Attwood Walmisley O pray for the peace of Jerusalem - Howells Drop, drop, slow tears – Robert Graham Hymns: 686, 489, 473 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Benjamin Bachmann Psalm 107 – Lawrence Thain Canticles: Evening Service in A – Herbert Sumsion Anthem: God so loved the world – John Stainer Hymns: 577, 160 15 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Canticles: Third Service – Philip Moore Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Hymns: 678, 474 18 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LENT 5 Introit: Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Service: Missa Brevis – Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Psalm 51 – T. Tertius Noble Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Motet: The crown of roses – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Hymns: 471, 443, 439 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 51 – Jeffrey Smith Canticles: Short Service – Orlando Gibbons Anthem: Aus tiefer Not – Felix Mendelssohn Hymns: 141, 151 3 22 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: William Byrd Psalm 103 – H. Walford Davies Canticles: Fauxbourdons – Thomas -

Composition Catalog

1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 New York Content & Review Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Marie Carter Table of Contents 229 West 28th St, 11th Floor Trudy Chan New York, NY 10001 Patrick Gullo 2 A Welcoming USA Steven Lankenau +1 (212) 358-5300 4 Introduction (English) [email protected] Introduction 8 Introduction (Español) www.boosey.com Carol J. Oja 11 Introduction (Deutsch) The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Translations 14 A Leonard Bernstein Timeline 121 West 27th St, Suite 1104 Straker Translations New York, NY 10001 Jens Luckwaldt 16 Orchestras Conducted by Bernstein USA Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach 18 Abbreviations +1 (212) 315-0640 Sebastián Zubieta [email protected] 21 Works www.leonardbernstein.com Art Direction & Design 22 Stage Kristin Spix Design 36 Ballet London Iris A. Brown Design Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited 36 Full Orchestra Aldwych House Printing & Packaging 38 Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra 71-91 Aldwych UNIMAC Graphics London, WC2B 4HN 40 Voice(s) & Orchestra UK Cover Photograph 42 Ensemble & Chamber without Voice(s) +44 (20) 7054 7200 Alfred Eisenstaedt [email protected] 43 Ensemble & Chamber with Voice(s) www.boosey.com Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein 45 Chorus & Orchestra Office, The Craig Urquhart Office, and the Berlin Library of Congress 46 Piano(s) Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock GmbH 46 Band Lützowufer 26 The “g-clef in letter B” logo is a trademark of 47 Songs in a Theatrical Style 10787 Berlin Amberson Holdings LLC. Deutschland 47 Songs Written for Shows +49 (30) 2500 13-0 2015 & © Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. 48 Vocal [email protected] www.boosey.de 48 Choral 49 Instrumental 50 Chronological List of Compositions 52 CD Track Listing LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 2 3 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 A Welcoming Leonard Bernstein’s essential approach to music was one of celebration; it was about making the most of all that was beautiful in sound. -

Leonard Bernstein

chamber music with a modernist edge. His Piano Sonata (1938) reflected his Leonard Bernstein ties to Copland, with links also to the music of Hindemith and Stravinsky, and his Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1942) was similarly grounded in a neoclassical aesthetic. The composer Paul Bowles praised the clarinet sonata as having a "tender, sharp, singing quality," as being "alive, tough, integrated." It was a prescient assessment, which ultimately applied to Bernstein’s music in all genres. Bernstein’s professional breakthrough came with exceptional force and visibility, establishing him as a stunning new talent. In 1943, at age twenty-five, he made his debut with the New York Philharmonic, replacing Bruno Walter at the last minute and inspiring a front-page story in the New York Times. In rapid succession, Bernstein Leonard Bernstein photo © Susech Batah, Berlin (DG) produced a major series of compositions, some drawing on his own Jewish heritage, as in his Symphony No. 1, "Jeremiah," which had its first Leonard Bernstein—celebrated as one of the most influential musicians of the performance with the composer conducting the Pittsburgh Symphony in 20th century—ushered in an era of major cultural and technological transition. January 1944. "Lamentation," its final movement, features a mezzo-soprano He led the way in advocating an open attitude about what constituted "good" delivering Hebrew texts from the Book of Lamentations. In April of that year, music, actively bridging the gap between classical music, Broadway musicals, Bernstein’s Fancy Free was unveiled by Ballet Theatre, with choreography by jazz, and rock, and he seized new media for its potential to reach diverse the young Jerome Robbins. -

INAUGURAL CONCERT Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: MISSA BREVIS in D, K194, Classics & Spirituals

The Choral Foundation in the Midwest Presents the INAUGURAL CONCERT Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: MISSA BREVIS IN D, K194, Classics & Spirituals The Summer Singers of Lee’s Summit & Chamber Orchestra Lynn Swanson & William O. Baker, DMA, Music Directors Steven McDonald, DMA, Organist Christine Freeman, soprano Jamea Sale, alto David White, tenor Michael Carter, bass Sunday Afternoon, 27 July 2014 St. Paul’s Episcopal Church Lee’s Summit, Missouri www.FestivalSingers.org The Summer Singers of Lee’s Summit William O. Baker, DMA Joseph Alsman Jennie Murphy Co-Music Director, Lee’s Summit David Armstrong Taura Owens Founder of the Choral Foundation Frances Armstrong Rebecca Palmer Nikki L. Banister Marjorie Peterson Lynn Swanson Michael Barnes Ruth Ann Phares Co- Music Director, Lee’s Summit Executive Associate of the Choral Foundation Toni Boehm Bruce Quaile *Jocelyn Botkin Charlotte Reynolds Christine Freeman Bridget Brown Carol Rothwell Associate Music Director/Senior Vocal Coach Mary K. Burrington Carole Runnenberger Darryl Chamberlain Vaughn Scarcliff Scott C. Smith Donna Chavez *Jim Schrock Choral Associate & Administrator, Atlanta Rachel Cheslik *Cindy Sheets Carl Chinnery Sarah Spilman Jamea Sale Amy Chinnery-Valmassei Nancy Stacy-Barrows Choral Assistant, Kansas City Carolyn Conner Joseph M. Steffen Charles Nelson Helen Darby Sandra Strawn Director, Northwest Georgia Summer Singers Pat DeMonbrun *Stephanie Sullivan Suzanne Fischer Lessie J. Thompson Amy Thropp Kenneth M. Frashier Don Thomson Director, Zimria Festivale Atlanta Linda Rene -

JEFFREY THOMAS Music Director

support materials for our recording of JOSEPH HAYDN (732-809): MASSES Tamara Matthews soprano - Zoila Muñoz alto Benjamin Butterfield tenor - David Arnold bass AMERICAN BACH SOLOISTS AMERICAN BACH CHOIR • PACIFIC MOZART ENSEMBLE Jeffrey Thomas, conductor JEFFREY THOMAS music director Missa in Angustiis — “Lord Nelson Mass” soprano soloist’s petition “Suscipe” (“Receive”) is followed by the unison choral response “deprecationem nostram” (“our Following the extraordinary success of his two so- prayer”). journs in London, Haydn returned in 1795 to his work as Kapellmeister for Prince Nikolas Esterházy the younger. The Even in the traditionally upbeat sections of the liturgy, Prince wanted Haydn to re-establish the Esterházy orchestra, the frequent turns to minor harmonies invoke the upheaval disbanded by his unmusical father, Prince Anton. Haydn’s re- wrought by war and disallow a sense of emotional—and au- turn to active duty for the Esterházy family did not, however, ditory—complacency. After the optimistic D-major opening signify a return to the isolated and static atmosphere of the of the Gloria, for example, the music slips into E minor at the relatively remote Esterházy palace, which had been given up words “et in terra pax hominibus” (“and peace to His people after the elder Prince Nikolas’s death in 1790. Haydn was now on earth”); throughout the section, D-minor inflections cloud able to work at the Prince’s residence in Vienna for most of the laudatory mood of the first theme and the text in general. the year, retiring to the courtly lodgings at Eisenstadt during The Benedictus is even more startling. -

Das Neugeborne Kindelein« Christmas Cantatas by Buxtehude · Telemann · J

»Das neugeborne Kindelein« Christmas Cantatas by Buxtehude · Telemann · J. S. Bach »Das neugeborne Kindelein« Christmas Cantatas La Petite Bande Anna Gschwend soprano Lucia Napoli alto Søren Richter tenor Christian Wagner bass Sigiswald Kuijken, Sara Kuijken, Anne Pekkala, Ortwin Lowyck violin Recorded at Paterskerk, Tielt (Belgium), on 16-18 December 2017 Marleen Thiers viola Recording producer: Olaf Mielke (MBM Musikproduktion Darmstadt (Germany) Executive producer: Michael Sawall Edouard Catalàn basse de violon Front illustration: “Adoration of the Shepherds”, Gerrit van Honthorst (1622), Vinciane Baudhuin, Ofer Frenkel oboe d‘amore [4-9] Pommersches Landesmuseum, Greifswald (Germany) Mario Sarrecchia organ Booklet editor & layout: Joachim Berenbold Translations: Jason F. Ortmann (English), Sylvie Coquillat (Français) + © 2018 note 1 music gmbh Sigiswald Kuijken CD manufactured in The Netherlands direction ENGLISH Christmas Cantatas Buxtehude · Telemann · Bach Dieterich Buxtehude (c 1637-1707) This recording includes the work of three great mas- and immediately moves us with his very simple and 1 Cantata »Das neugeborne Kindelein« BuxWV 13 6:39 ters dedicated to the theme of Christmas: Dietrich declamatory lyrical rendition, one which the instru- Buxtehude (1637-1707), Johann Sebastian Bach ments anticipate or echo. A perfect and charming Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) (1685-1750) and Georg Philipp Telemann (1681- work! Missa sopra »Ein Kindelein so löbelich« TWV 9:5 1767). All three created a large number of canta- The lyricist Cyriakus Schneegass (1546-1597) was 2 Kyrie 4:24 tas for many occasions, each according to his own an important Protestant pastor in Thuringia and also 3 Gloria 4:19 perspective and tradition. The Christmas cantatas composed and wrote various collections of hymns. -

Reception of Josquin's Missa Pange

THE BODY OF CHRIST DIVIDED: RECEPTION OF JOSQUIN’S MISSA PANGE LINGUA IN REFORMATION GERMANY by ALANNA VICTORIA ROPCHOCK Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Alanna Ropchock candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree*. Committee Chair: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Committee Member: Dr. L. Peter Bennett Committee Member: Dr. Susan McClary Committee Member: Dr. Catherine Scallen Date of Defense: March 6, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ........................................................................................................... i List of Figures .......................................................................................................... ii Primary Sources and Library Sigla ........................................................................... iii Other Abbreviations .................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... v Abstract ..................................................................................................................... vii Introduction: A Catholic -

A Concer T Tour of Krakow, Leipzig and Potsdam

A Concert Tour of Krakow, Leipzig and Potsdam Sung by Bristol Cathedral Choir July 2014 A Concert Tour of Krakow, Leipzig and Potsdam Thank you for coming to our concert, one of several we are giving as we bring our ancient music we are singing today in the centre of this programme. While you wait, why not learn a little about the Choir, and our wonderful city of Bristol? We hope you enjoy the music! Bristol Cathedral 2014 Bristol to Krakow Taking our music abroad has long been a passion of the Cathedral Choir. We are thrilled to be singing tonight in the ancient cultural capital of Poland! But our Polish adventure began in Bristol, at the city’s own Polish Church. Founded by Poles who fought for the Allies in WWII, the church of Our Lady of Ostrobrama now welcomes 350 worshippers each week. In June the Cathedral Choir sang for them, while they cooked for us. Our young choristers enjoyed all the traditional Polish delights, including kabanos, bigos, and smalec. NINE CENTURIES OF SONG A choir has been singing on the site of the Cathedral since the Augustinian monastery was founded in 1140. When the church formally became Bristol Cathedral in 1542 its statutes made provision for the development and maintenance of the choir, whose role was to sing the praises of God. 17 girls), all of whom are educated at Bristol Cathedral Choir School Bristol Cathedral Choral Foundation. Most join the choir as A Concert Tour of Krakow, Leipzig and Potsdam BRISTOL AT A GLANCE 12 ways to experience the very best the city has to offer Shop -

Celebrating Bernstein Flyer.Pdf

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018, 7.45pm Holy Trinity Sloane Square, SW1 Chichester Psalms Missa Brevis Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Conductor Mark Forkgen Tickets £25 (under-25s £15) to include a programme and interval drink. Box Office (020) 7730 4500, www.cadoganhall.com and at the door One of the most talented and successful musicians in American history, Leonard Bernstein was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, educator and humanitarian. His versatility as a composer is brilliantly illustrated in this concert to celebrate the centenary of his birth. The Dean of Chichester commissioned the Psalms for the 1965 Southern Cathedrals Festival with the request that the music should contain ‘a hint of West Side Story.’ Bernstein himself described the piece as ‘forthright, songful, rhythmic, youthful.’ Performed in Hebrew and Music Director: drawing on jazz rhythms and harmonies, the Psalms Mark Forkgen include an exuberant setting of ‘O be joyful In the Lord all ye lands’ (Psalm 100) and a gentle Psalm 23, ‘The Lord Nathan Mercieca is my shepherd’, as well as some menacing material cut countertenor from the score of the musical. Richard Pearce In 1988 Bernstein revisited the incidental music in organ medieval style that he had composed in 1955 for The Lark, Anouilh’s play about Joan of Arc, and developed Daniel de-Fry it into the vibrant Missa Brevis for unaccompanied choir, harp countertenor soloist and percussion. After three contrasting solo songs, the concert is Sacha Johnson and rounded off with a selection of favourite numbers from Alistair Marshallsay West Side Story, including Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, percussion America and Somewhere. -

MUSIC at MOUNT CARMEL

Twenty-seventh Sunday in Ordinary Time Second Sunday of Advent ABOUT THE PARISH October 7, 2018 December 9, 2018 Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the founding parish of all the English speaking congregations on the North Shore of Chicago, was Music of Healey Willan Music of William Ferris for harp and choir established in 1886. The present Indiana limestone structure Missa Brevis #1 Missa Adventus was built in 1913 in English Gothic style. The motif of the Blessed Art Thou, O Lord & O Sacred Feast On Jordan's Bank & Long is Our Winter exterior design is imitated in the Carrara marble work in the In salutari tuo anima mea, Gregorian chant Jerusalem surge, Gregorian chant sanctuary. A notable feature of the church is the splendid opalescent stained glass. The fine ribbed vault ceiling and dark Twenty-eighth Sunday in Ordinary Time Third Sunday of Advent oak woodwork further enhance the building’s warm ambience. October 14, 2018 December 16, 2018 Music of Thomas Luis da Victoria Missa Octavi Toni, Orlando di Lassus ABOUT THE MUSIC PROGRAM Missa "O Quam Gloriosum est Regnum" Rejoice in the Lord, anonymous Music has always played an important role in the liturgical life of the parish, and this tradition flourishes to this day. With a rich Jesu Dulcis Memoria & Tantum Ergo O Sacrum Convivium, Thomas Weelkes legacy of musical leadership including Adalbert Huguelet and Aufer a me opprobrium et contemptum, Gregorian Chant Gaudete in Domino semper, chant William Ferris that continues under the guidance of Paul French, the assembly has an opportunity to worship with music from the Twenty-ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time Fourth Sunday of Advent rich heritage of the Catholic Church, and is an active participant MUSIC at October 21, 2018 December 23, 2018 in all the liturgies through spirited singing of psalms, chants, (The Morning Choir and Treble Choir) Missa Emmanuel, Richard Proulx acclamations, hymns and songs. -

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) 1 1

AMERICAN CLASSICS BERNSTEIN Symphony No. 3 ‘Kaddish’ Claire Bloom, Narrator Kelley Nassief, Soprano The São Paulo Symphony Choir The Maryland State Boychoir The Washington Chorus Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop Missa Brevis (1988) 10:31 Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) 1 1. Kyrie 0:54 Missa Brevis • Symphony No. 3 ‘Kaddish’ • The Lark 2 2. Gloria 2:52 3 3. Sanctus 1:17 In the original version of Leonard Bernstein’s Symphony Symphony Orchestra celebrating the orchestra’s 75th No. 3, the speaker – reciting words that no doubt came anniversary in 1955. The mid-fifties were a remarkably 4 4. Benedictus 1:22 directly from the composer’s heart – proclaims, “As long busy time for Bernstein – between 1953 and 1957 he 5 5. Agnus Dei 1:57 as I sing, I shall live.” Singers, both solo and choral, figure composed a film score, incidental music for The Lark, 6 6. Dona nobis pacem 2:09 prominently in many of Bernstein’s works; clearly he three musicals and a violin concerto. He also assumed considered the human voice one of the most expressive musical directorship of the New York Philharmonic in Symphony No. 3 ‘Kaddish’ (Original version, 1963) 42:32 instruments in a composer’s arsenal. This program 1958, so the delay in composing the symphony was not 7 Ia. Invocation 3:15 features three examples of his vocal art. surprising. He began work in earnest during the summer 8 Ib. Kaddish 1 4:58 Bernstein first considered turning the choruses he of 1961 on Martha’s Vineyard, and continued during the 9 IIa.