Stylistic Features of the Compositions of the Modern American Composer Peter Williams, Particularly As Found in His Missa Brevis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

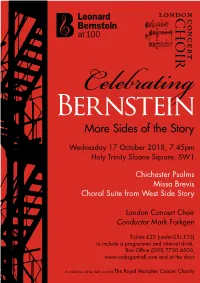

Bernsteincelebrating More Sides of the Story

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018, 7.45pm Holy Trinity Sloane Square, SW1 Chichester Psalms Missa Brevis Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Conductor Mark Forkgen Tickets £25 (under-25s £15) to include a programme and interval drink. Box Office (020) 7730 4500, www.cadoganhall.com and at the door A collection will be held in aid of The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity One of the most talented and successful musicians in American history, Leonard Bernstein was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, educator and humanitarian. His versatility as a composer is brilliantly illustrated in this concert to celebrate the centenary of his birth. The Dean of Chichester commissioned the Psalms for the 1965 Southern Cathedrals Festival with the request that the music should contain ‘a hint of West Side Story.’ Bernstein himself described the piece as ‘forthright, songful, rhythmic, youthful.’ Performed in Hebrew and drawing on jazz rhythms and harmonies, the Psalms Music Director: include an exuberant setting of ‘O be joyful In the Lord all Mark Forkgen ye lands’ (Psalm 100) and a gentle Psalm 23, ‘The Lord is my shepherd’, as well as some menacing material cut Nathan Mercieca from the score of the musical. countertenor In 1988 Bernstein revisited the incidental music in Richard Pearce medieval style that he had composed in 1955 for organ The Lark, Anouilh’s play about Joan of Arc, and developed it into the vibrant Missa Brevis for unaccompanied choir, countertenor soloist and percussion. Anneke Hodnett harp After three contrasting solo songs, the concert is rounded off with a selection of favourite numbers from Sacha Johnson and West Side Story, including Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, Alistair Marshallsay America and Somewhere. -

LCOM182 Lent & Eastertide

LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC Lent, Holy Week, and Eastertide 2018 GRACE CATHEDRAL 2 LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC GRACE CATHEDRAL SAN FRANCISCO LENT, HOLY WEEK, AND EASTERTIDE 2018 11 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LÆTARE Introit: Psalm 32:1-6 – Samuel Wesley Service: Collegium Regale – Herbert Howells Psalm 107 – Thomas Attwood Walmisley O pray for the peace of Jerusalem - Howells Drop, drop, slow tears – Robert Graham Hymns: 686, 489, 473 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Benjamin Bachmann Psalm 107 – Lawrence Thain Canticles: Evening Service in A – Herbert Sumsion Anthem: God so loved the world – John Stainer Hymns: 577, 160 15 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Canticles: Third Service – Philip Moore Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Hymns: 678, 474 18 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LENT 5 Introit: Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Service: Missa Brevis – Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Psalm 51 – T. Tertius Noble Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Motet: The crown of roses – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Hymns: 471, 443, 439 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 51 – Jeffrey Smith Canticles: Short Service – Orlando Gibbons Anthem: Aus tiefer Not – Felix Mendelssohn Hymns: 141, 151 3 22 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: William Byrd Psalm 103 – H. Walford Davies Canticles: Fauxbourdons – Thomas -

"Ei, Dem Alten Herrn Zoll' Ich Achtung Gern'"

Stephanie Klauk, Rainer Kleinertz, Sergi Zauner Zur Edition der Werke von Tomás Luis de Victoria Geschichte und Perspektiven Tomás Luis de Victoria (ca. 1548–1611) genoss bereits zu Lebzeiten internationalen Ruhm. Aus Ávila stammend war er lange Zeit in Rom – dort zudem mit einem deutlichen Bezug zu Deutschland1 – und schließlich wieder in Spanien tätig, so dass Drucke, Abschriften und Editionen seiner Werke gerade in den genannten Ländern nicht überraschen. Bisher liegen zwei im engeren Sinne musikwissenschaftliche (Gesamt-) Ausgaben seiner Werke vor: Opera omnia in acht Bänden, herausgegeben von Felipe Pedrell (Leipzig 1902–1913) und Opera omnia in vier Bänden, herausgegeben von Higinio Anglés (Barcelona 1965–1968).2 Unabhängig davon, dass die Ausgabe von Anglés ein Torso blieb, entsprechen beide Ausgaben weder nach Maßstäben der Vollständigkeit noch der Edition heutigen wissenschaftlichen Standards. Sie basieren nahezu ausschließlich auf den zu Lebzeiten des Komponisten erschienenen Drucken seiner Werke:3 • Motecta quae partim quaternis, partim quinis, alia senis, alia octonis vocibus concinuntur (Venedig 1572) 1 Auch wenn es keinerlei Belege für einen Aufenthalt Victorias in Deutschland gibt, so steht seine beson- dere Beziehung zu Deutschland außer Frage. Neben seinen vielfältigen Verbindungen zum Collegium Germanicum in Rom, an dem er zunächst Schüler, später Musiklehrer war, widmete Victoria zwei seiner Drucke politischen und kirchlichen deutschen Persönlichkeiten. Basierend auf der Widmung seiner Motecta (Venedig 1572) an den Bischof von Augsburg und Kardinal Otto Truchsess von Waldburg (1514– 1573) entwarf Raffaele Casimiri die Hypothese, Victoria habe von 1568 bis 1571 als Nachfolger Jacobus de Kerles die private Kapelle des Kardinals geleitet (Raffaele Casimiri, Il Vittoria. Nuovi Documenti per una biografia sincera di Tommaso Ludovico de Victoria, in: Note d’Archivio per la Storia Musicale 11 [1934], S. -

Composition Catalog

1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 New York Content & Review Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Marie Carter Table of Contents 229 West 28th St, 11th Floor Trudy Chan New York, NY 10001 Patrick Gullo 2 A Welcoming USA Steven Lankenau +1 (212) 358-5300 4 Introduction (English) [email protected] Introduction 8 Introduction (Español) www.boosey.com Carol J. Oja 11 Introduction (Deutsch) The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Translations 14 A Leonard Bernstein Timeline 121 West 27th St, Suite 1104 Straker Translations New York, NY 10001 Jens Luckwaldt 16 Orchestras Conducted by Bernstein USA Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach 18 Abbreviations +1 (212) 315-0640 Sebastián Zubieta [email protected] 21 Works www.leonardbernstein.com Art Direction & Design 22 Stage Kristin Spix Design 36 Ballet London Iris A. Brown Design Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited 36 Full Orchestra Aldwych House Printing & Packaging 38 Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra 71-91 Aldwych UNIMAC Graphics London, WC2B 4HN 40 Voice(s) & Orchestra UK Cover Photograph 42 Ensemble & Chamber without Voice(s) +44 (20) 7054 7200 Alfred Eisenstaedt [email protected] 43 Ensemble & Chamber with Voice(s) www.boosey.com Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein 45 Chorus & Orchestra Office, The Craig Urquhart Office, and the Berlin Library of Congress 46 Piano(s) Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock GmbH 46 Band Lützowufer 26 The “g-clef in letter B” logo is a trademark of 47 Songs in a Theatrical Style 10787 Berlin Amberson Holdings LLC. Deutschland 47 Songs Written for Shows +49 (30) 2500 13-0 2015 & © Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. 48 Vocal [email protected] www.boosey.de 48 Choral 49 Instrumental 50 Chronological List of Compositions 52 CD Track Listing LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 2 3 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 A Welcoming Leonard Bernstein’s essential approach to music was one of celebration; it was about making the most of all that was beautiful in sound. -

Paul Collins (Ed.), Renewal and Resistance Journal of the Society

Paul Collins (ed.), Renewal and Resistance PAUL COLLINS (ED.), RENEWAL AND RESISTANCE: CATHOLIC CHURCH MUSIC FROM THE 1850S TO VATICAN II (Bern: Peter Lang, 2010). ISBN 978-3-03911-381-1, vii+283pp, €52.50. In Renewal and Resistance: Catholic Church Music from the 1850s to Vatican II Paul Collins has assembled an impressive and informative collection of essays. Thomas Day, in the foreword, offers a summation of them in two ways. First, he suggests that they ‘could be read as a collection of facts’ that reveal a continuing cycle in the Church: ‘action followed by reaction’ (1). From this viewpoint, he contextualizes them, demonstrating how collectively they reveal an ongoing process in the Church in which ‘(1) a type of liturgical music becomes widely accepted; (2) there is a reaction to the perceived in- adequacies in this music, which is then altered or replaced by an improvement ... The improvement, after first encountering resistance, becomes widely accepted, and even- tually there is a reaction to its perceived inadequacies—and on the cycle goes’ (1). Second, he notes that they ‘pick up this recurring pattern at the point in history where Roman Catholicism reacted to the Enlightenment’ (3). He further contextualizes them, revealing how the pattern of action and reaction—or renewal and resistance—explored in this particular volume is strongly influenced by the Enlightenment, an attempt to look to the power of reason as a more beneficial guide for humanity than the authority of religion and perceived traditions (4). As the Enlightenment -

JEFFREY THOMAS Music Director

support materials for our recording of JOSEPH HAYDN (732-809): MASSES Tamara Matthews soprano - Zoila Muñoz alto Benjamin Butterfield tenor - David Arnold bass AMERICAN BACH SOLOISTS AMERICAN BACH CHOIR • PACIFIC MOZART ENSEMBLE Jeffrey Thomas, conductor JEFFREY THOMAS music director Missa in Angustiis — “Lord Nelson Mass” soprano soloist’s petition “Suscipe” (“Receive”) is followed by the unison choral response “deprecationem nostram” (“our Following the extraordinary success of his two so- prayer”). journs in London, Haydn returned in 1795 to his work as Kapellmeister for Prince Nikolas Esterházy the younger. The Even in the traditionally upbeat sections of the liturgy, Prince wanted Haydn to re-establish the Esterházy orchestra, the frequent turns to minor harmonies invoke the upheaval disbanded by his unmusical father, Prince Anton. Haydn’s re- wrought by war and disallow a sense of emotional—and au- turn to active duty for the Esterházy family did not, however, ditory—complacency. After the optimistic D-major opening signify a return to the isolated and static atmosphere of the of the Gloria, for example, the music slips into E minor at the relatively remote Esterházy palace, which had been given up words “et in terra pax hominibus” (“and peace to His people after the elder Prince Nikolas’s death in 1790. Haydn was now on earth”); throughout the section, D-minor inflections cloud able to work at the Prince’s residence in Vienna for most of the laudatory mood of the first theme and the text in general. the year, retiring to the courtly lodgings at Eisenstadt during The Benedictus is even more startling. -

Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the Rise of the Cäcilien-Verein

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2020 Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein Nicholas Bygate Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bygate, Nicholas, "Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein" (2020). WWU Graduate School Collection. 955. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/955 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein By Nicholas Bygate Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Bertil van Boer Dr. Timothy Fitzpatrick Dr. Ryan Dudenbostel GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Interim Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. -

Das Neugeborne Kindelein« Christmas Cantatas by Buxtehude · Telemann · J

»Das neugeborne Kindelein« Christmas Cantatas by Buxtehude · Telemann · J. S. Bach »Das neugeborne Kindelein« Christmas Cantatas La Petite Bande Anna Gschwend soprano Lucia Napoli alto Søren Richter tenor Christian Wagner bass Sigiswald Kuijken, Sara Kuijken, Anne Pekkala, Ortwin Lowyck violin Recorded at Paterskerk, Tielt (Belgium), on 16-18 December 2017 Marleen Thiers viola Recording producer: Olaf Mielke (MBM Musikproduktion Darmstadt (Germany) Executive producer: Michael Sawall Edouard Catalàn basse de violon Front illustration: “Adoration of the Shepherds”, Gerrit van Honthorst (1622), Vinciane Baudhuin, Ofer Frenkel oboe d‘amore [4-9] Pommersches Landesmuseum, Greifswald (Germany) Mario Sarrecchia organ Booklet editor & layout: Joachim Berenbold Translations: Jason F. Ortmann (English), Sylvie Coquillat (Français) + © 2018 note 1 music gmbh Sigiswald Kuijken CD manufactured in The Netherlands direction ENGLISH Christmas Cantatas Buxtehude · Telemann · Bach Dieterich Buxtehude (c 1637-1707) This recording includes the work of three great mas- and immediately moves us with his very simple and 1 Cantata »Das neugeborne Kindelein« BuxWV 13 6:39 ters dedicated to the theme of Christmas: Dietrich declamatory lyrical rendition, one which the instru- Buxtehude (1637-1707), Johann Sebastian Bach ments anticipate or echo. A perfect and charming Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) (1685-1750) and Georg Philipp Telemann (1681- work! Missa sopra »Ein Kindelein so löbelich« TWV 9:5 1767). All three created a large number of canta- The lyricist Cyriakus Schneegass (1546-1597) was 2 Kyrie 4:24 tas for many occasions, each according to his own an important Protestant pastor in Thuringia and also 3 Gloria 4:19 perspective and tradition. The Christmas cantatas composed and wrote various collections of hymns. -

Liszt and Christus: Reactionary Romanticism

LISZT AND CHRISTUS: REACTIONARY ROMANTICISM A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Robert Pegg May 2020 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Maurice Wright, Advisory Chair, Music Studies Dr. Michael Klein, Music Studies Dr. Paul Rardin, Choral Activities Dr. Christine Anderson, Voice and Opera, external member © Copyright 2020 by Robert Pegg All Rights Reserved € ii ABSTRACT This dissertation seeks to examine the historical context of Franz Lizt’s oratorio Christus and explore its obscurity. Chapter 1 makes note of the much greater familiarity of other choral works of the Romantic period, and observes critics’ and scholars’ recognition (or lack thereof) of Liszt’s religiosity. Chapter 2 discusses Liszt’s father Adam, his religious and musical experiences, and his influence on the young Franz. Chapter 3 explores Liszt’s early adulthood in Paris, particularly with respect to his intellectual growth. Special attention is given to François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand and the Abbé Félicité de Lamennais, and the latter’s papal condemnation. After Chapter 4 briefly chronicles Liszt’s artistic achievements in Weimar and its ramifications for the rest of his work, Chapter 5 examines theological trends in the nineteenth century, as exemplified by David Friedrich Strauss, and the Catholic Church’s rejection of such novelties. The writings of Charles Rosen aid in decribing the possible musical ramifications of modern theology. Chapter 6 takes stock of the movements for renewal in Catholic music, especially the work of Prosper Gueranger and his fellow Benedictine monks of Solesmes, France, and of the Society of Saint Cecilia in Germany. -

Die Öffnung Des Horizonts Bruckners Reise Nach Frankreich Vorfreude Programm Programm Auf Die Erste Bruckner Orgelnacht Und Bruckners „Neunte“

15. - 21. August 2015 DIE ÖFFNUNG DES HORIZONTS Bruckners Reise nach Frankreich Vorfreude PROGRAMM PROGRAMM AUF DIE ERSTE Bruckner Orgelnacht UND BRUCKNERS „Neunte“ PONTIFIKALAMT · EINTRITT FREI LIEDerabeND · EINHEITSPREis € 25,- Samstag, 15. August 2015, 10.00 Uhr / Stiftsbasilika Montag, 17. August 2015, 20.00 Uhr / Marmorsaal A. Bruckner: „Windhaager Messe“ für Alt, R. Schumann: Eichendorff-Vertonungen 2 Hörner und Orgel, WAB 25 Liederkreis op. 39 „Ave Maria“ für Alt und Orgel, WAB 7 Werke von O. Schoeck, H. Wolf und französischen J. S. Bach: Fuge Es-Dur BWV 552/2 Komponisten Irene Wallner, Alt Alois Mühlbacher, Mezzosopran Josefin Bergmayr-Pfeiffer und Georg Viehböck, Horn Franz Farnberger, Klavier Matthias Giesen, Orgel KaMMERKONZERT · EINHEITSPREis € 25,- SALON · Buchpräsentation · EINTRITT FREI Dienstag, 18. August 2015, 20.00 Uhr / Sala Terrena Sonntag, 16. Aug. 2015, 11.30 Uhr / Altomonte-Saal L. v. Beethoven: Streichquartett B-Dur aus op. 18/6 „Die Bruckner-Bestände des Stiftes St. Florian“ C. Debussy: Streichquartett g-Moll op. 10 Katalog Teil 2: Das Bruckner-Archiv (Gruppe 13-23) A. Bruckner: Streichquintett F-Dur, WAB 112 von Elisabeth Maier und Renate Grasberger Minetti Quartett Werke von J. Brahms, F. Chopin und A. Bruckner Peter Langgartner, Bratsche Florian Eschelmüller, Klavier BRUCKNER-ORGELNACHT · EINHEITSPREis € 30,- ERÖFFNUNGSKONZERT · PREISE € 40,- / 30,- / 20,- Mittwoch, 19. August 2015, 20.00 bis 0.45 Uhr Sonntag, 16. August 2015, 20.00 Uhr / Marmorsaal Stiftsbasilika / Visualisierung · Orgelbar A. Bruckner: Motette „Virga Jesse“ 20.00 Uhr · Johann Vexo, Nancy/Paris – „Frankreich“ (Transkription: Erich Kaufmann) 21.00 Uhr · Simon Johnson, London – „England“ Th. Mandel: Konzert für Klavier und Streicher 22.00 Uhr · Daniel Glaus, Bern – „The Composer plays“ (Uraufführung) 23.00 Uhr · Giampaolo di Rosa, Rom – „Orgel plus“ P. -

A Chronicle of the Reform: Catholic Music in the 20Th Century by Msgr

A Chronicle of the Reform: Catholic Music in the 20th Century By Msgr. Richard J. Schuler Citation: Cum Angelis Canere: Essays on Sacred Music and Pastoral Liturgy in Honour of Richard J. Schuler. Robert A. Skeris, ed., St. Paul MN: Catholic Church Music Associates, 1990, Appendix—6, pp. 349-419. Originally published in Sacred Music in seven parts. This study on the history of church music in the United States during the 20th century is an attempt to recount the events that led up to the present state of the art in our times. It covers the span from the motu proprio Tra le solicitudini, of Saint Pius X, through the encyclical Musicae sacra disciplina of Pope Pius XII and the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council and the documents that followed upon it. In knowing the course of development, musicians today may build on the accomplishments of the past and so fulfill the directives of the Church. Cum Angelis Canere, Appendix 6 Part 1: Tra le sollicitudini The motu proprio, Tra le sollicitudini, issued by Pope Pius X, November 22, 1903, shortly after he ascended the papal throne, marks the official beginning of the reform of the liturgy that has been so much a part of the life of the Church in this century. The liturgical reform began as a reform of church music. The motu proprio was a major document issued for the universal Church. Prior to that time there had been some regulations promulgated by the Holy Father for his Diocese of Rome, and these instructions were imitated in other dioceses by the local bishops. -

Reception of Josquin's Missa Pange

THE BODY OF CHRIST DIVIDED: RECEPTION OF JOSQUIN’S MISSA PANGE LINGUA IN REFORMATION GERMANY by ALANNA VICTORIA ROPCHOCK Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Alanna Ropchock candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree*. Committee Chair: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Committee Member: Dr. L. Peter Bennett Committee Member: Dr. Susan McClary Committee Member: Dr. Catherine Scallen Date of Defense: March 6, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ........................................................................................................... i List of Figures .......................................................................................................... ii Primary Sources and Library Sigla ........................................................................... iii Other Abbreviations .................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... v Abstract ..................................................................................................................... vii Introduction: A Catholic