Stephen B. Elkins and the Benjamin Harrison Campaign and Cabinet, 1887-1891

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record-House. April 24

5476 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. APRIL 24, By Mr. WILSON of lllinois: A bill (H. R. 15397) granting a. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. pension to Carl Traver-to the Committee on Invalid Pensions. Also, a bill (H. R. 15398) to remove the charge of desertion from SUNDAY, .April24, 190.4-. the military record of GeorgeS. Green-to the Committee on Mil The House met at 12 o'clock m. itary Affairs. The following prayer was offered by the Chaplain, Rev. H.E..--rn.Y N. COUDEN, D. D.: PETITIONS, ETC. Eternal and everliving God, our Heavenly Father, we thank Thee for that deep and ever-abiding faith which Thou hast im Under clause 1 of Rn1e XXII, the following petitions and papers planted in the hearts of men, and which has inspired the true, the were laid on the Clerk's desk and referred as follows: noble, the brave of every age with patriotic zeal and fervor, bring By Mr. BRADLEY: Petition of Montgomery Grange, of Mont gomery, N.Y., and others, in favor of the passage of bill H. R. ing light out of darkness, order out of chaos, liberty out of bond 9302-to the Committee on Ways and Means. age, and thus contributing here a. little, there a. little, to the By Mr. CALDERHEAD: Petition of Lamar Methodist Episco splendid civilization of our age. Especially do we thank Thee for pal Church, of Lamar Kans., in favor of the Hepburn-Dolliver that long line of illustrious men who lived and wrought, suffered bill-to the Committee on the Judiciary. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

Saturday, March 04, 1893

.._ I I CONGRESSIONAL ; PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES QF THE FIUY-THIRD CONGRESS. SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE. - ' SEN.ATE. ADDRESS OF THE VICE-ERESIDENT. The VICE-PRESIDENT. Senators, 'tleeply impressed with a S.A.TURlY.A.Y, Ma.rch 4, 1893. sense of its responsibilities and of its dignities, I now enter upon Hon. ADLAI E. STEVENSON, Vice-President _of the United the discharge of the duties of the high office to wJ:lich I have States, having taken the oath of office at the close of the last been called. regular session of the Fifty-second Congress, took the Qhair. I am not unmindful of the fact that among the occupants of this chair during the one hundred and four years of our consti PRAYER. tutional history have been statesmen eminent alike for their tal Rev. J. G. BUTLER, D. D., Chaplain to the Senate, offered the ents and for their tireless devotion to public duty. Adams, Jef following prayer: ferson, and Calhoun honored its incumbency during the early 0 Thou, with whom is no variableness or shadow of turning, days of the Republic, while Arthur, Hendricks, and Morton the unchangeable God, whose throne stands forever, and whose have at a later period of our history shed lust.er upon the office dominion ruleth over all; we seek a Father's blessing as we wait of President of the most august deliberatiVe assembly known to at the mercy seat. We bring to Thee our heart homage, God of men. our fathers, thanking Thee fqr our rich heritage of faith and of I assums the duties of the great trust confided to me with no freedom, hallowed bv the toils and tears, the valor and blood feeling of self-confidence, but rather with that of grave distrust and prayers, of our patriotdead. -

Schuyler Colfax Collection L036

Schuyler Colfax collection L036 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit August 03, 2015 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Rare Books and Manuscripts 140 North Senate Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana, 46204 317-232-3671 Schuyler Colfax collection L036 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical Note.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 Series 1: Correspondence, 1782-1927.....................................................................................................9 Series 2: Subject files, 1875-1970.........................................................................................................32 -

To the William Howard Taft Papers. Volume 1

THE L I 13 R A R Y 0 F CO 0.: G R 1 ~ ~ ~ • P R I ~ ~ I I) I ~ \J T ~' PAP E R ~ J N 1) E X ~ E R IE S INDEX TO THE William Howard Taft Papers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS • PRESIDENTS' PAPERS INDEX SERIES INDEX TO THE William Ho-ward Taft Papers VOLUME 1 INTRODUCTION AND PRESIDENTIAL PERIOD SUBJECT TITLES MANUSCRIPT DIVISION • REFERENCE DEPARTMENT LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON : 1972 Library of Congress 'Cataloging in Publication Data United States. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Index to the William Howard Taft papers. (Its Presidents' papers index series) 1. Taft, William Howard, Pres. U.S., 1857-1930. Manuscripts-Indexes. I. Title. II. Series. Z6616.T18U6 016.97391'2'0924 70-608096 ISBN 0-8444-0028-9 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $24 per set. Sold in'sets only. Stock Number 3003-0010 Preface THIS INDEX to the William Howard Taft Papers is a direct result of the wish of the Congress and the President, as expressed by Public Law 85-147 approved August 16, 1957, and amended by Public Laws 87-263 approved September 21, 1961, and 88-299 approved April 27, 1964, to arrange, index, and microfilm the papers of the Presidents in the Library of Congress in order "to preserve their contents against destruction by war or other calamity," to make the Presidential Papers more "readily available for study and research," and to inspire informed patriotism. Presidents whose papers are in the Library are: George Washington James K. -

Congressional Record-House. '

t712 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. JANUARY 10 ' PETITIONS, ETC. By Mr. LINDSAY: Petition of Federation of Jewish Or Under clause 1 of Rule XXII, the following petitions and pa g~izations, for a chaplain in army and navy for Jewish sol pers were laid on the Clerk's desk and referred as follows : dters-to the Committee on Military Affairs. By Mr. ASHBROOK: Petition of citizens of Coshocton Coun ~lso, yeti_ti?n _of Merchants' Association of New York, against ty, Ohio, against S. 3940 (Jolmston Sunday law)-to the Com le~tslation mrmtcal to the well-being of railways-to the Com mittee on the District of Columbia. · nnttee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. Also, paper to accompany bill for relief of Gifford Ramey By Mr. MOON of Tennessee : Paper to accompany bills for (previously referred to the Committee on Invalid Pensions) relief of .James_F. Campbell (H. R. 24262)-to the Committee - to the Committee on Pensions. on Invalid Pensions. By Mr. BENNET of New York: Petition of National Woman's Also, paper to accompany bill for relief of Sarah A. Weber Christian Temperance Union, for legislation to protect prohibi to the Committee on Invalid Pensions. tion States from interstate liquor traffic-to the Committee on By Mr. SULZER: Petition of American Prison Association the Judiciary. favoring suitable appropriation for the entertainment of th~ By Mr. CALDER: Petition of London Wine and Spirits .Com Congress of the International Prison Commission-to the Com- pany, against reduction of tariff on foreign liquors-to th~ Com mittee on the Judiciary. · mittee on Ways and Means. -

Atlantic Union Gleaner for 1906

,z.:,,,e,-,?e,mv,:ms,.50,:,x.ww:.g.gmtnng,,,:gio,?&,),.._:,;,,,tx,,>,:,,,,,*.g,(.15,t, 4xty,(w...m.y,:gwagmm4i,,,,,,wh-zpgsva.gfx, 6 le,,VA(VA4ekge et, ? 41.<4 ,V c 0 ':P ATLANTIC ION 1[z ,. c NE 04.1%r7 4-sp - 7"7 • ,.- GL4E ;\:' ' C 1 4.., • A- fegi: *- ,(- e a; , 4., • ,,'8 .,;(. = (1.-,;?:-- ,<.> ,s'e. k?. ., k:".. ... 2-- P:.••• kf'..›,(t - (i••• ;•..,<-1.- k *> ;-. X** ? K= 0 ;:i:., (i.? fa, (4*e 2 ;.?_> ;NL>,;,,,:?.>(% ,;• ..,:t> - ,(•.•- ,:: b . ,:?.,,' 2 :*- ,<•?...- <4xt4 , , kl, 2• A.,3 3, k 1-• %:1- :q ?... e 2 k> ;.,. :- e.... ,';i= ;, i- a• ,,c:, 2, 1%31 : - "Lift up your eyes, and look on the fields; for they are white already to harvest." VoL. V SOUTH LANCASTER, MASS., OCTOBER 24, 1906 No. 42 FALLING LEAVES. was, may be learned in some degree fruitful field be counted for a forest." by seeing nature when it puts on its Amid such scenes of beauty will be FALLING, falling, gently falling leaf and bloom, and the gentle zeph- the home of the redeemed. Are the leaves to-day, In the orchard, in the forest, yrs play among the trees. In the Eden home man was given By the broad highway. In that garden was every tree that dominion over every beast of the Let us all a lesson gather was pleasant to look upon and that was field, and every fowl of the air. Be- From the falling leaves: good for food, unmarred by the curse cause of sin, this dominion was lost, Soon will come the time of harvest, that came upon the earth because of and the fear of them came upon man. -

Congressional Record

... CONGRESSIONAL RECORD. PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE FIFTY-SIXTH CONGRESS. FIRST SESSION. He is, therefore, to have and to hold the said office, together with all the SENATE. rights, :powers, and privileges thereunto belonging, or by law in anywise ap~ertaming, until the next meeting of the legislature of the Common wealth 1\IONDAY, December 4, 1899. of Pennsylvania, or until his successor shall be duly elected and qualified, i! he shall so long behave himself well. The first Monday of December being the day prescri.bed by the 'l'his appointment to compute from the day of the date hereof. Constitution of the United States for the annual meetmg of Con Given under my hand and the great seal of the State at the city of Harris burg, this 21st day of April, in the year of our Lord 1899, and of the Common gress, the first session of the Fifty-sixth Congress commenced wealth the one hundred and twenty·third. this day. [SEAL.] WILLIAM A. STONE. The Senate assembled in its Chamber at the Capitol. By the governor: The PRESIDENT pro "tempore (Mr. WILLIAM P. FRYE, a Sen W. W. GRIEST, ator from the State of Maine) took the chair and called the Secretary of the Commonwealth. Senate to order at 12 o'clock noon. Mr. COCKRELL. I move that the credential'! be referred to the Committee on Privileges and Elections. PRAYER. Mr. CHANDLER. '!'here isnoobjection to that course. I sub Rev. W. H. MILBURN, D. D., Chaplain to the Senate, offered mit a resolution which I ask may be referred at the same time. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 (7-81) EXP United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory—Nomination Form date entered JUN 1 7 1982, See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ali entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Proctor-Clement House and/or common Clement House 2. Location street & number Field Avenue city, town Rutland N/A vicinity of state Vermont code 50 county Rutland code 021 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious —— object N/A C __ in process yes: restricted government scientific ( __ being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation X no military 4. Owner of Property name Mr. Mark Foley street & number Field Avenue city, town Rutland N/A vicinity of state Vermon! 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Rutland County Courthouse street & number "S£ Center Street city, town Rutland state Vermont 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Vermont Historic Sites and Structures "as this property been determined eligible? yes X no Survey date August 1976 . federal X state . county local depository for survey records Vermont Division for Historic Preservation city, town Montpelier state Vermont 7. Description Condition Check one Check one X excellent deteriorated X unaltered X original site good rqins altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Proctor-Clement House is a two-story, three-by-two bay, Italianate style wood-frame residence with a hipped roof and central belvedere. -

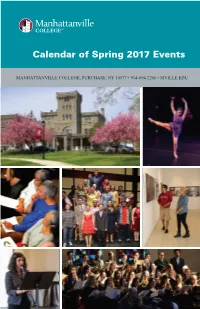

Calendar of Spring 2017 Events

Calendar of Spring 2017 Events MANHATTANVILLE COLLEGE, PURCHASE, NY 10577 • 914-694-2200 • MVILLE.EDU January Events Monday, January 23 – Friday, February 17 Tamara Kwark, “Constraints: A Collection of Straightjackets” Brownson Gallery Exhibition presented by the Studio Art Department Opening Reception: Wednesday, January 25, 5 – 7 p.m. For further information contact [email protected] Tuesday, January 24 – Friday, March 3 Sheila M. Fane, “Layers of Art” Arthur M. Berger Gallery Exhibition presented by the Studio Art Department Opening Reception: Saturday, January 28, 3 – 5 p.m. Closing Reception: Tuesday, February 28, 4 – 7 p.m. For further information contact [email protected] February Events Wednesday, February 1 • 6:00 p.m. African Heritage/Black History Month Opening Ceremony West Room, Reid Castle Journalist Rae Gomes ’08 Distinguished Alumni Awardee MC – Rev. Doris K. Dalton, Exec. Director – Westchester MLK Institute for Nonviolence For further information contact [email protected] Wednesday, February 1 • 4:30 p.m. • Faculty Lecture Series MAPing Academic Literacy: Reading Meets Writing Through Scaffolded Blogging Library (News and Events Room) Courtney Kelly, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Chair, Literacy and Carleigh Brower, Director, Andrew Bodenrader Center for Academic Writing and Composition For further information contact [email protected] Thursday, February 2 – Sunday, February 5th “Pajama Game” Little Theatre Book by George Abbott and Richard Bissell Music and Lyrics by Richard Adler and Jerry Ross Mark Cherry, Director and Musical Director Presented by the Departments of Music and Dance and Theatre Thursday, Friday, Saturday at 8 p.m. and Sunday at 2 p.m. -

“A People Who Have Not the Pride to Record Their History Will Not Long

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE i “A people who have not the pride to record their History will not long have virtues to make History worth recording; and Introduction no people who At the rear of Old Main at Bethany College, the sun shines through are indifferent an arcade. This passageway is filled with students today, just as it was more than a hundred years ago, as shown in a c.1885 photograph. to their past During my several visits to this college, I have lingered here enjoying the light and the student activity. It reminds me that we are part of the past need hope to as well as today. People can connect to historic resources through their make their character and setting as well as the stories they tell and the memories they make. future great.” The National Register of Historic Places recognizes historic re- sources such as Old Main. In 2000, the State Historic Preservation Office Virgil A. Lewis, first published Historic West Virginia which provided brief descriptions noted historian of our state’s National Register listings. This second edition adds approx- Mason County, imately 265 new listings, including the Huntington home of Civil Rights West Virginia activist Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the New River Gorge Bridge, Camp Caesar in Webster County, Fort Mill Ridge in Hampshire County, the Ananias Pitsenbarger Farm in Pendleton County and the Nuttallburg Coal Mining Complex in Fayette County. Each reveals the richness of our past and celebrates the stories and accomplishments of our citizens. I hope you enjoy and learn from Historic West Virginia. -

The Political Career of Stephen W

37? N &/J /V z 7 PORTRAIT OF AN AGE: THE POLITICAL CAREER OF STEPHEN W. DORSEY, 1868-1889 DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Sharon K. Lowry, M.A. Denton, Texas May, 19 80 @ Copyright by Sharon K. Lowry 1980 Lowry, Sharon K., Portrait of an Age: The Political Career of Stephen W. Dorsey, 1868-1889. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1980, 447 pp., 6 tables, 1 map, bibliography, 194 titles. The political career of Stephen Dorsey provides a focus for much of the Gilded Age. Dorsey was involved in many significant events of the period. He was a carpetbagger during Reconstruction and played a major role in the Compromise of 1877. He was a leader of the Stalwart wing of the Republican party, and he managed Garfield's 1880 presidential campaign. The Star Route Frauds was one of the greatest scandals of a scandal-ridden era, and Dorsey was a central figure in these frauds. Dorsey tried to revive his political career in New Mexico after his acquittal in the Star Route Frauds, but his reputation never recovered from the notoriety he received at the hands of the star route prosecutors. Like many of his contemporaries in Gilded Age politics, Dorsey left no personal papers which might have assisted a biographer. Sources for this study included manuscripts in the Library of Congress and the New Mexico State Records Center and Archives in Santa Fe; this study also made use of newspapers, records in the National Archives, congressional investigations of Dorsey printed in the reports and documents of the House and Senate, and the transcripts of the star route trials.