Final Report of Rail Network Strategic Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E-News N21 Coul.Qxp

The electronic newsletter of the International Union of Railways n°21 - 7th September 2006 Proximity with UIC members Latest news FS: Innocenzo Cipolletta appointed President, Mauro Moretti new Chief Executive Officer Mr. Innocenzo Cipolletta, an Economist, who has been during 10 years Director General of the Italian confederation Confindustria, is appointed as the new President of FS Group. Mr. Mauro Moretti, who was previously the Amminstratore Delegato (CEO) of Rete Ferroviaria Italiana (RFI), the Italian railway infrastructure manager -and currently President of the UIC Infrastructure Forum at international level- is appointed as the new Amministratore Delegato Innocenzo Cipolletta Mauro Moretti (CEO) of the Italian railways FS Group. They are succeeding Elio Catania who is leaving the Italian Railways Group. UIC conveys its sincere congratulations to Mr. Cipolletta and Mr. Moretti for theses appoint- ments and many thanks to Mr. Elio Catania for his action in UIC. Information session for representatives from Russian railways at UIC HQ A group of 25 representati- ves from Russian railways participating to a study trip in France visited the UIC Headquarters in Paris on Monday 28th August. Members of this delegation were general directors, senior managers and engi- 1 neers from the Russian rail- L L L way companies and a series of rail- way organisations. The represented in particular JSC Russian Railways (RZD), October Railways (Saint- Petersburg), Oural SA, VNIIAS (Ministère), and cooperating compa- nies as Radioavionika, etc. This information session on UIC role and activities was opened by UIC Chief Executive Luc Aliadière. By wel- coming the delegation, Luc Aliadière underlined the promising perspectives resulting from Russian railways' mem- bership in UIC and from the enhanced cooperation between RZD and UIC in a series of strategic cooperation issues: development of Euro-Asian corridors, partnership in business, technology and research, training, etc. -

Transport in the Cumberland Community Research Report June 2020

Transport in the Cumberland Community Research Report June 2020 Document Set ID: 8005199 Version: 9, Version Date: 13/08/2020 Report prepared by the Social Research and Planning Team, Community and Place, Cumberland City Council 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Cumberland City Council acknowledges the Darug Nation and People as the traditional custodians of the land on which the Cumberland Local Government Area is situated and pays respect to Aboriginal Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples as the First Peoples of Australia. Cumberland City Council also acknowledges other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples living and working in the Cumberland Local Government Area. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF PARTICIPANTS Cumberland City Council would like to acknowledge and thank everyone who participated in this research. This report would not have been possible without your time and willingness to share your stories and experiences. Document Set ID: 8005199 Version: 9, Version Date: 13/08/2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents findings from research into key transport and mobility challenges for the Cumberland community. This research was conducted between August 2019 and April 2020 and is grounded in empirical data sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and Transport for NSW, amongst other sources, and extensive community engagement. Quality transport options are fundamental to accessing many essential services, education, employment and social and recreational activities. Although three train lines run through the Cumberland LGA, in addition to the T80 high frequency bus route, many Cumberland residents still have difficulties getting around. Major barriers raised by the community relate to reliability, frequency and coverage of services. -

Presentation Heading Subheading / Author / Date

Sydney Metro Macquarie Park briefings May 2019 1 Goodbye Station Link Opening 26 May 2019 Sydney Metro North West Services • The Sydney Metro is Australia’s first fully Every automated driverless passenger railway mins system 4 in peak • No timetables - just turn up and go: o 15 services an hour during peak o 37 minute trip between Tallawong and Chatswood Station Every o Opal enabled mins Up to 1,100 people per train. 10 o off peak Travel Calculator Travelling to Macquarie University Station from: • Rouse Hill approx. 24min to Macquarie University • Kellyville approx. 22min • Bella Vista approx. 19min • Norwest approx. 17min • Hills Showground approx. 15min Tallawong • Castle Hill approx. 13min • Cherrybrook approx. 10min • Epping approx. 4min Metro train features Sydney Metro – Accessibility First accessible railway: • Level access between platforms and trains • Wider Opal gates • Accessible toilets • Multiple elevators at stations to platforms • Kerb ramps and accessible Kiss and Ride drop-off /pick-up points • Tactile flooring • Braille on help points and audio service announcements. Sydney Metro safety and operations Parking spaces Metro phasing period • First 6 weeks, Metro trains will operate every 5 mins at peak • To complete additional works we will replace metro services with North West Night Buses over the next 6 months. North West Night Buses will provide: o Turn up and go services o 10 min frequency • North West Night Buses will commence in both directions between Tallawong and Chatswood after the last Metro service: o Tallawong approx. 9:30pm o Chatswood approx. 10:00pm. North West Night Buses frequency North West Night Buses Services every 10 mins An all stop and limited stop services will run between Chatswood and Tallawong Stations for the next 6 months. -

Overview of the English Rail System

House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts Overview of the English rail system Tenth Report of Session 2021–22 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 1 July 2021 HC 170 Published on 7 July 2021 by authority of the House of Commons The Committee of Public Accounts The Committee of Public Accounts is appointed by the House of Commons to examine “the accounts showing the appropriation of the sums granted by Parliament to meet the public expenditure, and of such other accounts laid before Parliament as the committee may think fit” (Standing Order No. 148). Current membership Meg Hillier MP (Labour (Co-op), Hackney South and Shoreditch) (Chair) Mr Gareth Bacon MP (Conservative, Orpington) Kemi Badenoch MP (Conservative, Saffron Walden) Shaun Bailey MP (Conservative, West Bromwich West) Olivia Blake MP (Labour, Sheffield, Hallam) Dan Carden MP (Labour, Liverpool, Walton) Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown MP (Conservative, The Cotswolds) Mr Mark Francois MP (Conservative, Rayleigh and Wickford) Barry Gardiner MP (Labour, Brent North) Peter Grant MP (Scottish National Party, Glenrothes) Antony Higginbotham MP (Conservative, Burnley) Mr Richard Holden MP (Conservative, North West Durham) Craig Mackinlay MP (Conservative, Thanet) Sarah Olney MP (Liberal Democrat, Richmond Park) Nick Smith MP (Labour, Blaenau Gwent) James Wild MP (Conservative, North West Norfolk) Powers Powers of the Committee of Public Accounts are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 148. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at https://www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright-parliament/. -

Choosing the Right Myzone Ticket

Choosing the right MyZone ticket PensionerExcursionTicket Unlimited daily travel ZA03659 Sydney and outer metropolitan areas GST incl. Valid on day of fi rst use only. Unlimited travel on all Sydney Buses, Newcastle Buses and Ferries, Sydney Ferries and CityRail services. Transport info: Excludes premium services. Ticket not transferable. www.131500.info Magnetic Strip Must be made available for inspection or processing by an authorised offi cer. Issued subject to the Transport Administration Act 1988, its Regulations and Orders. Fares effective 2 January 2012 Contents What’s MyZone? ______________ 2 Choosing your ticket ___________ 2 MyBus tickets _______________ 3-5 MyMulti tickets ______________ 6-7 MyMulti travel map ___________ 8-9 MyFerry tickets ____________ 10-11 MyTrain tickets ____________ 12-13 Pensioner Excursion tickets ______ 14 Family Funday Sunday tickets ____ 15 Metro Light Rail and Sydney Ferries network maps __ 16-17 MyMulti MyBus MyFerry tickets sold here Ticket resellers can be The information in this brochure is correct at easily identified by the the time of printing and is subject to change Save time MyZone/PrePay flag. without notice. What’s MyZone? MyBus tickets (bus-only travel) MyZone is the name of the public transport fare How do I know which is the right bus ticket? system encompassing travel by train, bus (government Select a MyBus1, MyBus2 or MyBus3 ticket according and private), government ferry and light rail. MyZone to how many sections you need to travel through on tickets are used across greater Sydney, the Blue your trip (a section is approximately 1.6 km). Mountains, Central Coast, the Illawarra, the Southern Highlands and the Hunter (excluding Newcastle Ferries and Newcastle Buses time-based fares). -

Tracking the Value of Rail Time Over Time Neil J

Institute of Transport Studies, Monash University World Transit Research World Transit Research 9-1-2011 Tracking the value of rail time over time Neil J. Douglas George Karpouzis Follow this and additional works at: http://www.worldtransitresearch.info/research Recommended Citation Douglas, N.J. & Karpouzis, G. (2011). Tracking the value of rail time over time. Conference paper delivered at the 34th Australasian Transport Research Forum (ATRF) Proceedings held on 28 - 30 September 2011 in Adelaide, Australia. This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by World Transit Research. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Transit Research by an authorized administrator of World Transit Research. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Australasian Transport Research Forum 2011 Proceedings 28 - 30 September 2011, Adelaide, Australia Publication website: http://www.patrec.org/atrf.aspx Tracking the value of rail time over time By Douglas N.J.1 and Karpouzis G.2 Neil Douglas is manager of Douglas Economics. George Karpouzis was chief economist at RailCorp and is now a consultant economist Abstract The value of rail time is an important economic parameter in the evaluation of many rail infrastructure projects, translating travel time savings into dollars to compare against project costs. For Sydney, the value of onboard train travel time has been estimated through Stated Preference market research. Three surveys have been undertaken over the last two decades. The first was undertaken in 1992; the second in 2003 and the third in 2010. Between 1992 and 2010, the value of time has been updated by reference to movements in fare and latterly by reference to wage rate indices. -

Transport for NSW 18 Lee Street, Chippendale NSW 20081 PO Box K659, Haymarket NSW 1240 Transport.Nsw.Gov.Au 1ABN 18 804 239 602 - 2 - 00793074

Transport NSW GOVERNMENT for NSW Our Ref: 00793074 Your Ref: R15/0016 Out-00028736 Ms Tara McCarthy Chief Executive Local Government NSW GPO Box 7003 SYDNEY NSW 2001 Dear Ms McCarthy Thank you for your correspondence on behalf of Local Government NSW about train services to the Liverpool Local Government Area and to growth and regional areas. Improving transport is important to our customers and essential to businesses and the NSW economy as we grow, so we have made tackling this issue a priority. For too long transport was neglected across NSW, so we are investing $51.2 billion in long overdue improvements in roads and public transport to ensure infrastructure keeps pace with our needs. As Liverpool City Council would be aware, the Liverpool area has already benefited from the substantial timetable improvements introduced in 2017. For example, express services via the T3 Bankstown Line were introduced, with six trains per hour and a journey time to the CBD of only 53 minutes. This is up to nine minutes faster than the journey via the T2 Leppington/lnner West Line. Nearly 90 per cent of Liverpool customers now have access to peak period turn-up-and-go services, with a train every 10 minutes or better. The T5 Cumberland Line was also provided 280 new services each week, including late night and weekend services. New direct links between Leppington, Parramatta and Blacktown further connect South West and North West Sydney. These changes have been a resounding success, with a 30 per cent growth in patronage from the South West to Parramatta. -

Railcorp Annual Report 2019-20 Volume 1

RailCorp Annual Report Volume 1 • 2019–20 RailCorp 20-44 Ennis Road Milsons Point NSW 2061 Contact us at: [email protected] This Annual Report was produced wholly by Annual Report 2019–20 Annual Report RailCorp. This Annual Report can be accessed on the Transport for NSW website transport.nsw.gov.au ISBN: 978-1-63684-453-4 © 2020 RailCorp Unless otherwise stated, all images (including photography, background images, icons and illustrations) are the property of RailCorp. Users are welcome to copy, reproduce and distribute the information contained in this report for non-commercial purposes only, provided ii acknowledgement is given to RailCorp as the source. RailCorp Letter to the Minister The Hon. Andrew Constance MP Minister for Transport and Roads Parliament House Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Dear Minister, It is our pleasure to provide the Rail Corporation New South Wales (RailCorp) Annual Report for the financial year, 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020, for your information and presentation to Parliament. This report has been prepared in accordance with the Annual Report (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984, the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Regulation 2015 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983. Yours sincerely Bruce Morgan Anne McDonald Chair Director 20 November 2020 Letter of submission • iii Foreword 2 From the Chief Executive 4 Overview 6 About RailCorp 8 Annual Report 2019–20 Annual Report Financial performance 9 Appendices 12 Contents Appendix 1: Changes in Acts and subordinate legislation from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020 -

ORR Best Practice Study Visit to Australia

ORR Best Practice Study Visit to Australia - 20 August to 05 September 2007 David Brace and Paul Dawkins (CDL Group) page 1 Contents Page No Executive Summary 4 1. Purpose 7 2. Introduction 8 3. Background 9 4. Issues 10 5. Funding and Financial Regulation 11 6. Findings 13 7. Safety and other Regulators 20 8. Other Meetings and Visits 24 Appendices A Meetings and Visits Schedule 29 B Papers Provided by Hosts 36 C Responses to Standard Set of Questions 38 } 2 Glossary of Acronyms ACCC The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission ARA Australasian Railway Association ARTC Australian Rail Track Corporation ATSB Australian Transport Safety Bureau BHP BHP Billiton World's largest resource company CASA Civil Aviation Safety Authority COMET Consortium of Metropolitan Transport Operators CPI Consumer Price Index CRC Co-operative Research Centre DoI Department of Infrastructure, Victoria DORC Depreciated Optimised Replacement Cost gmpta gross million tonnes per annum ICE Institution of Civil Engineers IPART Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal ISG Infrastructure Services Group (Queensland Rail) ITSRR Independent Transport Safety and Reliability Regulator OTSI Office of Transport Safety Investigation PDFH Passenger Demand Forecasting Handbook PLC Programme Logic Controller PPP Public Private Partnership QCA Queensland Competition Authority QRNA Queensland Rail Network Access QR Queensland Rail QT Queensland Transport RailBAMS Acoustic Bearing Monitor SCT Specialised Container Transport TIDC Transport Infrastructure Development Corporation TSC Transport Services Contract WILD Wheel Impact Loading Device Doc # 285015.013 Executive Summary The visit to Australia between 22 August and 04 September was arranged around 6½ full days of meetings, 1½ days of site visits and a full day asset management workshop. -

What Will Reform Mean for Britain's Railways?

148 HelpingNEWS ensure a sustainable future for UK rail freight July 2021 What will reform mean for Britain’s railways? Opportunity of a lifetime to grow freight if Great British Railways reform delivers on promises. P.3 First freight train for The Rail Freight Group (RFG) welcomed the creation of Great British Railways is a unique Port of Sunderland. publication of the Williams – Shapps Plan for opportunity to meet these ambitions if it ensures Rail, which offers the opportunity of a lifetime that private sector rail freight operators can to accelerate the growth of rail freight, flourish, and that customers and suppliers are helping decarbonise UK freight transport and encouraged to invest for growth.” meeting the needs of its customers. She added: “We look forward to working with Under the plans set out by Government a Government as they develop the detailed new organisation, Great British Railways, will proposals, including for reform of track access be created to plan and run the rail network, and a new role for the ORR. It will be essential incorporating Network Rail and passenger that the new structure and systems truly deliver P.4 services. Importantly, the new body will have a on their promise for rail freight.” statutory duty to promote freight, and a national Ports benefit from freight co-ordination team will be created to Reform has been widely welcomed across the 775m freight trains. improve the freight customer experience. freight sector. Eddie Aston, CEO for G&W’s Government will also set a growth target for rail UK/Europe Region companies, said: “We freight, as has been done in Scotland, and will welcome the publication of the Williams-Shapps issue guidance on its priorities for rail freight Plan for Rail. -

Meeting the Challenges for Future Mobility Sunday, May 22Nd

Meeting the challenges for future mobility nd Sunday, May 22 4:00 pm OPENING WELCOME DESKS 6:00 pm 6:00 pm WELCOME RECEPTION 9:00 pm rd Monday, May 23 8:30 am OPENING SESSION - Auditorium Vauban 9:30 am PLENARY SESSION 1: More services, more trains - Auditorium Vauban 10:30 am Poster Session & Coffee Break - Exhibition Hall Challenge D: Challenge E: Challenge F: A world of services Bringing the territories closer together Even more trains for passengers at higher speeds even more on time Room Pasteur Room Artois Room Van Gogh 1 Room Rubens Room Van Gogh 2 11:00 am D. SANZ J. GOIKOETXEA E. FONTANEL J. LANE D. DE ALMEIDA F1: D1: E1: E2: D2: Timetable planning Simplifying travel High speed Track & bridges Design for comfort & route conception using IT development maintenance for fl ow optimization 12:40 pm Lunch Break Challenge D: Challenge E: Challenge F: A world of services Bringing the territories closer together Even more trains for passengers at higher speeds even more on time Room Pasteur Room Artois Room Van Gogh 1 Room Rubens Room Van Gogh 2 2:30 pm K. GOTO M. GRIFFIN A. GAGGELLI B. GUIEU S. HIRAGURI D4: F2: D3: E3: E4: Passenger comfort: Train control Better information Pantograph Wheel & track measurement & signalling using IT Catenary Interaction constraints techniques for capacity 4:10 pm Poster Session & Coffee Break - Exhibition Hall Challenge E: Challenge C: Challenge F: Bringing the territo- Increasing freight capacity Even more trains even more ries closer together and services on time at higher speeds Room Van Gogh 1 Room Van Gogh 2 Room Pasteur Room Artois Room Rubens 4:40 pm M. -

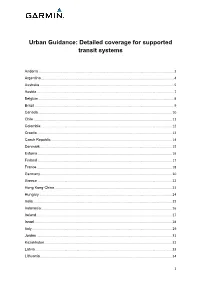

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia .................................................................................................................................................