Preserving the Stave Churches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fungi Associated with Three Common Bark Beetle Species in Norwegian

Preface Finally, two years of study for the master degree at the Norwegian University of Life Science is completed. This thesis is the end of my education in forestry science. It has been a long and sometimes challenging journey, but this is it. It started as a “worst case scenario”, when I had to change my thesis assignment. Two months of fieldwork resulted in nothing due to unlucky circumstances. I was saved by the hero Dr. Halvor Solheim who is my main supervisor. He came up with the idea of study fungi associated with some bark beetle species. This thesis has given me the opportunity to practice and learn about new fields, that I thought I never would bother to try to understand. I’ve been working with tree samples, beetle species and DNA! Normally I was the one who usually prayed, that DNA wouldn’t be a subject in the examinations. In additions to Dr. Halvor Solheim, many people have inspired, helped and motivated me through the whole process. They have answered all my questions and have been there for me when I needed help. Dr. Paal Krokene for advisements and borrowing out literature. Senior Engineers Helge Meissner and Anne Eskild Nilsen for instructions and advising in the biochemistry lab. Senior Research Scientist Ari M. Hietala for advising me about the laboratory methods and the writing process. Lead Engineer Inger M. Heldal for advisements and mixing of different solutions, such as primers and enzymes. Lead Engineer Gro Wollebæk for the advisements and instructions for the laboratory work. Scientific Adviser Torstein Kvamme for assisting with the fieldwork, beetle identification and comments on the manuscript. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

Vegliste Desember 2020

Vegliste 2020 TØMMERTRANSPORT Fylkes- og kommunale vegar Desember 2020 Vestland www.vegvesen.no/veglister Foto: Torbjørn Braset Adm.område / telefon / heimeside: Adm.område Telefon Heimeside Vestland fylkeskommune 05557 www.vlfk.no Alver 56 37 50 00 www.alver.kommune.no Askvoll 57 73 07 00 www.askvoll.kommune.no Askøy 56 15 80 00 www.askoy.kommune.no Aurland 57 63 29 00 www.aurland.kommune.no Austevoll 55 08 10 00 www.austevoll.kommune.no Austrheim 56 16 20 00 www.austrheim.kommune.no Bergen 55 56 55 56 www.bergen.kommune.no| Bjørnafjorden 56 57 50 00 www.bjornafjorden.kommune.no Bremanger 57 79 63 00 www.bremanger.kommune.no Bømlo 53 42 30 00 www.bomlo.kommune.no Eidfjord 53 67 35 00 www.eidfjord.kommune.no Etne 53 75 80 00 www.etne.kommune.no Fedje 56 16 51 00 www.fedje.kommune.no Fitjar 53 45 85 00 www.fitjar.kommune.no Fjaler 57 73 80 00 www.fjaler.kommune.no Gulen 57 78 20 00 www.gulen.kommune.no Gloppen 57 88 38 00 www.gloppen.kommune.no Hyllestad 57 78 95 00 www.hyllestad.kommune.no Kvam 56 55 30 00 www.kvam.kommune.no Kvinnherad 53 48 31 00 www.kvinnherad.kommune.no Luster 57 68 55 00 www.luster.kommune.no Lærdal 57 64 12 00 www.laerdal.kommune.no Masfjorden 56 16 62 00 www.masfjorden.kommune.no Modalen 56 59 90 00 www.modalen.kommune.no Osterøy 56 19 21 00 www.osteroy.kommune.no Samnanger 56 58 74 00 www.samnanger.kommune.no Sogndal 57 62 96 00 https://www.sogndal.kommune.no Solund 57 78 62 00 www.solund.kommune.no Stad 57 88 58 00 www.stad2020.no Stord 53 49 66 00 www.stord.kommune.no Stryn 57 87 47 00 www.stryn.kommune.no Sunnfjord -

© Georgina Green ~ Epping Forest Though the Ages

© Georgina Green ~ Epping Forest though the Ages Epping Forest Preface On 6th May 1882 Queen Victoria visited High Beach where she declared through the Ages "it gives me the greatest satisfaction to dedicate this beautiful Forest to the use and enjoyment of my people for all time" . This royal visit was greeted with great enthusiasm by the thousands of people who came to see their by Queen when she passed by, as their forefathers had done for other sovereigns down through the ages . Georgina Green My purpose in writing this little book is to tell how the ordinary people have used Epping Fo rest in the past, but came to enjoy it only in more recent times. I hope to give the reader a glimpse of what life was like for those who have lived here throughout the ages and how, by using the Forest, they have physically changed it over the centuries. The Romans, Saxons and Normans have each played their part, while the Forest we know today is one of the few surviving examples of Medieval woodland management. The Tudor monarchs and their courtiers frequently visited the Forest, wh ile in the 18th century the grandeur of Wanstead House attracted sight-seers from far and wide. The common people, meanwhile, were mostly poor farm labourers who were glad of the free produce they could obtain from the Forest. None of the Forest ponds are natural . some of them having been made accidentally when sand and gravel were extracted . while others were made by Man for a variety of reasons. -

Einar Oscar Schous Arkitektur 1900-1915

«...HAM SELV TIL HÆDER, ALLE BERGENSERNES ØINE TIL GLÆDE...» Einar Oscar Schous arkitektur 1900-1915 TEKSTDEL Ingfrid Bækken HOVEDFAGSOPPGAVE I KUNSTHISTORIE UNIVERSITETET I BERGEN NOVEMBER 1998 «...HAM SELV TIL HÆDER, ALLE BERGENSERNES ØINE TIL GLÆDE...» Einar Oscar Schous arkitektur 1900-1915 TEKSTDEL Ingfrid Bækken HOVEDFAGSOPPGAVE I KUNSTHISTORIE UNIVERSITETET I BERGEN NOVEMBER 1998 Formgivning: Per Bækken EINAR OSCAR SCHOU INNHOLD KAPITTEL 1. INNLEDNING . .9 1.1. OPPGAVENS FORMÅL . .9 1.2. DE UTVALGTE BYGNINGENE . .11 1.3. SCHOU SOM JUGENDARKITEKT . .11 1.4. ART NOUVEAU/JUGEND . .12 Begreper . .14 1.5. NORSK JUGENDARKITEKTURS FORSKNINGSHISTORIE . .14 1.6. EINAR OSCAR SCHOU . .16 KAPITTEL 2. FRA NYRENESSANSE TIL JUGEND. DEN NATIONALE SCENE . .19 2.1 EKSTERIØR . .20 Planløsning . .20 Den additive oppbygningen . .20 Sokkeletasjen . .21 Hovedfasaden . .22 Sidefasadene . .22 Vertikalitet - horisontalitet . .23 Veggflatens utforming . .23 Det dekorative formspråket . .24 Det organiske uttrykket . .26 2.2. INTERIØR . .27 Helhetsvirkning . .27 Dekorative elementer . .28 Møbler og lamper . .29 2.3. KONKURRANSEUTKASTET . .30 Nyrenessanse . .30 Horisontalitet . .31 Helhetsvirkning . .31 2.4. BEARBEIDELSEN AV KONKURRANSEPROSJEKTET . .32 Tidlige skisser og prosjekter . .32 Schak Bull og arbeidsutvalget . .34 2.5. MULIGE FORBILDER . .34 De øvrige konkurranseutkastene . .34 Dramatiska Teatern i Stockholm . .35 Kontinentale forbilder . .36 Interims Hoftheater i Stuttgart . .37 Teatrene i Meran og Dortmund . .37 KAPITTEL 3. DET GEOMETRISKE FORMSPRÅKET . .41 3.1. KALFARLIEN 18 . .41 Bygningskroppen . .41 Fargebruk . .42 Taket . .42 Vinduene . .43 Verandaen . .43 Det dekorative formspråket . .44 Det «romantiske» og det engelske preget . .44 5 Den bergenske tone . .45 Planløsning . .46 Interiør . .46 Hagen . .46 3.2. KONG OSCARS GATE 70 . .47 Fasadene . .47 Dekorative detaljer . -

Lasting Legacies

Tre Lag Stevne Clarion Hotel South Saint Paul, MN August 3-6, 2016 .#56+0).')#%+'5 6*'(7674'1(1742#56 Spotlights on Norwegian-Americans who have contributed to architecture, engineering, institutions, art, science or education in the Americas A gathering of descendants and friends of the Trøndelag, Gudbrandsdal and northern Hedmark regions of Norway Program Schedule Velkommen til Stevne 2016! Welcome to the Tre Lag Stevne in South Saint Paul, Minnesota. We were last in the Twin Cities area in 2009 in this same location. In a metropolitan area of this size it is not as easy to see the results of the Norwegian immigration as in smaller towns and rural communities. But the evidence is there if you look for it. This year’s speakers will tell the story of the Norwegians who contributed to the richness of American culture through literature, art, architecture, politics, medicine and science. You may recognize a few of their names, but many are unsung heroes who quietly added strands to the fabric of America and the world. We hope to astonish you with the diversity of their talents. Our tour will take us to the first Norwegian church in America, which was moved from Muskego, Wisconsin to the grounds of Luther Seminary,. We’ll stop at Mindekirken, established in 1922 with the mission of retaining Norwegian heritage. It continues that mission today. We will also visit Norway House, the newest organization to promote Norwegian connectedness. Enjoy the program, make new friends, reconnect with old friends, and continue to learn about our shared heritage. -

Stadnamn I Luster Kommune I Indre Sogn

Universitetet i Bergen Institutt for lingvistiske, litterære og estetiske studiar Stadnamn i Luster kommune i Indre Sogn Ein prototypebasert analyse av namnelandskapet i eit vestlandsk jordbruksdistrikt Samuele Mascetti NOLISP350 Mastergradsoppgåve i nordisk Vår 2017 Føreord Å skriva denne masteravhandlinga har vore for meg fyrst og fremst ei personleg fordjuping i tankegangen og levemåten typiske for både staden eg kjem frå og staden eg har valt å bu på: Alpane og Vestlandet. Eg er fødd og oppvaksen i ei lita fjellbygd ved Comosjøen i nordlege Lombardia fylke i Nord-Italia, ved grensa mot Sveits. Det alpine innsjølandskapet har mykje til felles med fjordlandskapet på Vestlandet: Høge, bratte fjell som stuper i vatnet, djupe og grisgrendte dalar, dårlege vegar og mykje, mykje regn. Kulturlandskapet er òg nokso likt: Jordbruket var lenge hovudnæringa i det alpine området, og stølinga spelte ei sentral rolle i den tradisjonelle gardsordninga. Det norditalienske setersystemet er nesten identisk med det vestlandske og dei fleste bruka har to setrar: Heimesetra (kalla munt, ‘fjell’ på lombardisk), som ligg om lag mellom 600 og 1400 moh. og er nytta vår og haust, og langsetra (kalla alp, ‘høgfjell’ på lombardisk), som ligg om lag mellom 1500 og 2500 moh. og er nytta om sumaren. Dei fleste bygdene ligg mellom 200 og 600 moh., so begge setrar er utstyrde med stølshus, sidan dei ligg fleire timar gonge frå heimehusa. Som gutunge var eg mang ein sumar på selet hans bestefar og fekk oppleva den gamle stølstradisjonen, som diverre alt då var døyande: Dei fleste gardsbrukarane la driftene ned pga. den uoverkomelege økonomiske sentraliseringa i jordbrukspolitikken til EU-landa, som trengte dei småe produsentane ut til fordel for dei store industrialiserte bruka i låglandet kring storbyane. -

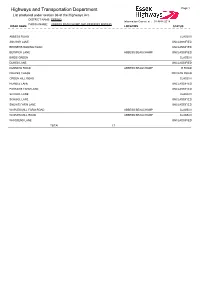

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List Produced Under Section 36 of the Highways Act

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: ABBESS BEAUCHAMP AND BERNERS RODING ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS ABBESS ROAD CLASS III ANCHOR LANE UNCLASSIFIED BERNERS RODING ROAD UNCLASSIFIED BERWICK LANE ABBESS BEAUCHAMP UNCLASSIFIED BIRDS GREEN CLASS III DUKES LANE UNCLASSIFIED DUNMOW ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP B ROAD FRAYES CHASE PRIVATE ROAD GREEN HILL ROAD CLASS III HURDLE LANE UNCLASSIFIED PARKERS FARM LANE UNCLASSIFIED SCHOOL LANE CLASS III SCHOOL LANE UNCLASSIFIED SNOWS FARM LANE UNCLASSIFIED WAPLES MILL FARM ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP CLASS III WAPLES MILL ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP CLASS III WOODEND LANE UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 17 Highways and Transportation Department Page 2 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: BOBBINGWORTH ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS ASHLYNS LANE UNCLASSIFIED BLAKE HALL ROAD CLASS III BOBBINGWORTH MILL BOBBINGWORTH UNCLASSIFIED BRIDGE ROAD CLASS III EPPING ROAD A ROAD GAINSTHORPE ROAD UNCLASSIFIED HOBBANS FARM ROAD BOBBINGWORTH UNCLASSIFIED LOWER BOBBINGWORTH GREEN UNCLASSIFIED MORETON BRIDGE CLASS III MORETON ROAD CLASS III MORETON ROAD UNCLASSIFIED NEWHOUSE LANE UNCLASSIFIED PEDLARS END UNCLASSIFIED PENSON'S LANE UNCLASSIFIED STONY LANE UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 15 Highways and Transportation Department Page 3 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: -

Church of Norway Pre

You are welcome in the Church of Norway! Contact Church of Norway General Synod Church of Norway National Council Church of Norway Council on Ecumenical and International Relations Church of Norway Sami Council Church of Norway Bishops’ Conference Address: Rådhusgata 1-3, Oslo P.O. Box 799 Sentrum, N-0106 Oslo, Norway Telephone: +47 23 08 12 00 E: [email protected] W: kirken.no/english Issued by the Church of Norway National Council, Communication dept. P.O. Box 799 Sentrum, N-0106 Oslo, Norway. (2016) The Church of Norway has been a folk church comprising the majority of the popu- lation for a thousand years. It has belonged to the Evangelical Lutheran branch of the Christian church since the sixteenth century. 73% of Norway`s population holds member- ship in the Church of Norway. Inclusive Church inclusive, open, confessing, an important part in the 1537. At that time, Norway Church of Norway wel- missional and serving folk country’s Christianiza- and Denmark were united, comes all people in the church – bringing the good tion, and political interests and the Lutheran confes- country to join the church news from Jesus Christ to were an undeniable part sion was introduced by the and attend its services. In all people. of their endeavor, along Danish king, Christian III. order to become a member with the spiritual. King Olav In a certain sense, the you need to be baptized (if 1000 years of Haraldsson, and his death Church of Norway has you have not been bap- Christianity in Norway at the Battle of Stiklestad been a “state church” tized previously) and hold The Christian faith came (north of Nidaros, now since that time, although a permanent residence to Norway in the ninth Trondheim) in 1030, played this designation fits best permit. -

Taosrewrite FINAL New Title Cover

Authenticity and Architecture Representation and Reconstruction in Context Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Ruth First zaal van de Universiteit op maandag 10 november 2014 om 10.15 uur door Robert Curtis Anderson geboren op 5 april 1966 te Brooklyn, New York, USA Promotores: prof. dr. K. Gergen prof. dr. A. de Ruijter Overige leden van de Promotiecommissie: prof. dr. V. Aebischer prof. dr. E. Todorova dr. J. Lannamann dr. J. Storch 2 Robert Curtis Anderson Authenticity and Architecture Representation and Reconstruction in Context 3 Cover Images (top to bottom): Fantoft Stave Church, Bergen, Norway photo by author Ise Shrine Secondary Building, Ise-shi, Japan photo by author King Håkon’s Hall, Bergen, Norway photo by author Kazan Cathedral, Moscow, Russia photo by author Walter Gropius House, Lincoln, Massachusetts, US photo by Mark Cohn, taken from: UPenn Almanac, www.upenn.edu/almanac/volumes 4 Table of Contents Abstract Preface 1 Grand Narratives and Authenticity 2 The Social Construction of Architecture 3 Authenticity, Memory, and Truth 4 Cultural Tourism, Conservation Practices, and Authenticity 5 Authenticity, Appropriation, Copies, and Replicas 6 Authenticity Reconstructed: the Fantoft Stave Church, Bergen, Norway 7 Renewed Authenticity: the Ise Shrines (Geku and Naiku), Ise-shi, Japan 8 Concluding Discussion Appendix I, II, and III I: The Venice Charter, 1964 II: The Nara Document on Authenticity, 1994 III: Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, 2003 Bibliography Acknowledgments 5 6 Abstract Architecture is about aging well, about precision and authenticity.1 - Annabelle Selldorf, architect Throughout human history, due to war, violence, natural catastrophes, deterioration, weathering, social mores, and neglect, the cultural meanings of various architectural structures have been altered. -

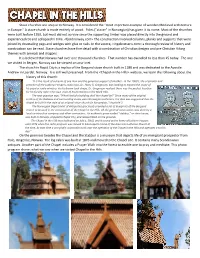

Stave Churches Are Unique to Norway. It Is Considered the "Most Important Example of Wooden Medieval Architecture in Europe." a Stave Church Is Made Entirely of Wood

Stave churches are unique to Norway. It is considered the "most important example of wooden Medieval architecture in Europe." A stave church is made entirely of wood. Poles ("staver" in Norwegian) has given it its name. Most of the churches were built before 1350, but most did not survive since the supporting timber was placed directly into the ground and experienced rot and collapsed in time. <fjordnorway.com> The construction involved columns, planks and supports that were joined by dovetailing pegs and wedges with glue or nails. In the source, <ingebretsens.com> a thorough review of history and construction can be read. Stave churches have fine detail with a combination of Christian designs and pre‐Christian Viking themes with animals and dragons. It is believed that Norway had over one thousand churches. That number has dwindled to less than 25 today. The one we visited in Bergen, Norway can be viewed on acuri.net. The church in Rapid City is a replica of the Borgund stave church built in 1180 and was dedicated to the Apostle Andrew in Laerdal, Norway. It is still well preserved. From the <Chapel‐in the‐Hills> website, we learn the following about the history of this church: "It is the result of a dream of one man and the generous support of another...In the 1960's, the originator and preacher of the Lutheran Vespers radio hour, Dr. Harry R. Gregerson, was looking to expand the scope of his popular radio ministry. As his dream took shape, Dr. Gregerson realized there was the perfect location for his facility right in his own state of South Dakota in the Black Hills.