The Daylighting of the Stave Church of Borgund 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

© Georgina Green ~ Epping Forest Though the Ages

© Georgina Green ~ Epping Forest though the Ages Epping Forest Preface On 6th May 1882 Queen Victoria visited High Beach where she declared through the Ages "it gives me the greatest satisfaction to dedicate this beautiful Forest to the use and enjoyment of my people for all time" . This royal visit was greeted with great enthusiasm by the thousands of people who came to see their by Queen when she passed by, as their forefathers had done for other sovereigns down through the ages . Georgina Green My purpose in writing this little book is to tell how the ordinary people have used Epping Fo rest in the past, but came to enjoy it only in more recent times. I hope to give the reader a glimpse of what life was like for those who have lived here throughout the ages and how, by using the Forest, they have physically changed it over the centuries. The Romans, Saxons and Normans have each played their part, while the Forest we know today is one of the few surviving examples of Medieval woodland management. The Tudor monarchs and their courtiers frequently visited the Forest, wh ile in the 18th century the grandeur of Wanstead House attracted sight-seers from far and wide. The common people, meanwhile, were mostly poor farm labourers who were glad of the free produce they could obtain from the Forest. None of the Forest ponds are natural . some of them having been made accidentally when sand and gravel were extracted . while others were made by Man for a variety of reasons. -

Traveling Portals Suspicious Item They Could Find Was His Diary

by a search the secret police had conducted in his house. The only TRAVelING PORTals suspicious item they could find was his diary. Apparently it did not contain enough evidence to take him to prison, and he even got it Mari Lending back. In an artistic rage, and trying to make sure that his personal notes could not be read again by anyone, he burned his diary. The Master and Margarita remained secret even after his death in 1940, and could not be published until 1966, when the phrase became In the early 1890s, the Times of London reported on a lawsuit on the 1 Times ( London ), more frequently used by dissidents to show their resistance to the pirating of plaster casts. With reference to a perpetual injunction June 2, 1892. state regime. In the early nineties, when the KGB archives were partly granted by the High Court of Justice, Chancery Division, it was 2 Times ( London ), opened, his diary was found. Apparently, during the confiscation, announced that “ various persons in the United Kingdom of Great February 14, 1894. the KGB had photocopied the diary before they returned it to the Britain and Ireland have pirated, and are pirating, casts and models ” author. made by “ D. BRUCCIANI and Co., of the Galleria delle Belle Arti, The best guardians are oftentimes ultimately the ones you would 40. Russell Street, Covent Garden ” and consequently severely vio least expect. lated the company’s copyright “ which is protected by statute. ” The defendant, including his workmen, servants, and agents, was warned against “ making, selling, or disposing of, or causing, or permitting to be made, sold, or disposed of, any casts or models taken, or copied, or only colourably different, from the casts or models, the sole right and property of and in which belongs to the said D. -

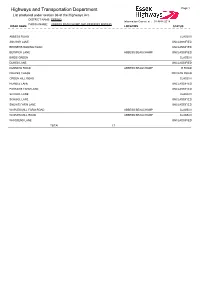

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List Produced Under Section 36 of the Highways Act

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: ABBESS BEAUCHAMP AND BERNERS RODING ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS ABBESS ROAD CLASS III ANCHOR LANE UNCLASSIFIED BERNERS RODING ROAD UNCLASSIFIED BERWICK LANE ABBESS BEAUCHAMP UNCLASSIFIED BIRDS GREEN CLASS III DUKES LANE UNCLASSIFIED DUNMOW ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP B ROAD FRAYES CHASE PRIVATE ROAD GREEN HILL ROAD CLASS III HURDLE LANE UNCLASSIFIED PARKERS FARM LANE UNCLASSIFIED SCHOOL LANE CLASS III SCHOOL LANE UNCLASSIFIED SNOWS FARM LANE UNCLASSIFIED WAPLES MILL FARM ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP CLASS III WAPLES MILL ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP CLASS III WOODEND LANE UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 17 Highways and Transportation Department Page 2 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: BOBBINGWORTH ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS ASHLYNS LANE UNCLASSIFIED BLAKE HALL ROAD CLASS III BOBBINGWORTH MILL BOBBINGWORTH UNCLASSIFIED BRIDGE ROAD CLASS III EPPING ROAD A ROAD GAINSTHORPE ROAD UNCLASSIFIED HOBBANS FARM ROAD BOBBINGWORTH UNCLASSIFIED LOWER BOBBINGWORTH GREEN UNCLASSIFIED MORETON BRIDGE CLASS III MORETON ROAD CLASS III MORETON ROAD UNCLASSIFIED NEWHOUSE LANE UNCLASSIFIED PEDLARS END UNCLASSIFIED PENSON'S LANE UNCLASSIFIED STONY LANE UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 15 Highways and Transportation Department Page 3 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: -

Hertfordshire & Essex List of Affected Streets

Water Supply Problems- Hertfordshire & Essex List of affected streets: ABBESS ROAD CHAPEL FIELDS FULLERS MEAD KILN ROAD ABBEY CLOSE CHAPEL LANE FYFIELD ROAD KING HENRYS WALK ALEXANDER MEWS CHELMSFORD ROAD GAINSTHORPE ROAD KINGS WOOD PARK ALLMAINS CLOSE CHESTNUT WALK GARNON MEAD KINGSDON LANE ANCHOR LANE CHEVELY CLOSE GEORGE AVEY CROFT KINGSTON FARM ROAD ARAGON MEWS CHURCH LANE GIBB CROFT LABURNUM ROAD ARCHER CLOSE CHURCH ROAD GIBSON CLOSE LAKE VIEW ARCHERS CLATTERFORD END CUT GLOVERS LANE LANCASTER ROAD ARDLEY CRESCENT COLEMANS FARM LANE GOULD CLOSE LARKSWOOD ASHLYNS LANE COLEMANS LANE GRANVILLE ROAD LATTON COMMON ROAD BACK LANE COLVERS GREEN CLOSE LATTON GREEN BASSETT GARDENS COMMON ROAD GREEN FARM LANE LATTON HOUSE BEAMISH CLOSE COMMONSIDE ROAD GREEN HILL ROAD LATTON STREET BEAUFORT CLOSE COOPERSALE COMMON GREEN LANE LAUNDRY LANE BELCHERS LANE CRIPSEY AVENUE GREENMAN ROAD LITTLE LAVER ROAD BENTLEYS CROSS LEES LANE GREENS FARM LANE LODGE HALL BERECROFT CUNNINGHAM RISE GREENSTED CHURCH LANE LONDON ROAD BERWICK LANE DOWNHALL ROAD GREENSTED ROAD LONG WOOD BETTS LANE DUCK LANE GREENWAYS LOWER BOBBINGWORTH BIRCH VIEW DUKES CLOSE HAMPDEN CLOSE GREEN BLACKHORSE LANE DUNMOW ROAD HARLOW COMMON MALTINGS HILL BLAKE HALL ROAD ELIZABETH CLOSE HARLOW ROAD MANDEVILLE CLOSE BLENHEIM SQUARE ELM CLOSE HARRISON DRIVE MARKWELL WOOD BLENHEIM WAY ELM GARDENS HASTINGWOOD PARK MATCHING GREEN BLUEMANS ELMBRIDGE HALL HASTINGWOOD ROAD MATCHING LANE BLUEMANS END EMBERSON WAY HAWKS HILL MATCHING ROAD BOBBINGWORTH MILL EMBLEYS FARM ROAD HIGH ROAD MATCHING TYE ROAD -

Epping Forest District Council Representations to the Draft Local Plan Consultation 2016 (Regulation 18)

Epping Forest District Council Representations to the Draft Local Plan Consultation 2016 (Regulation 18) Stakeholder ID 4806 Name Bruce Banks Fairfield Fairbank Residents Association (FFRA) Method Survey Date This document has been created using information from the Council’s database of responses to the Draft Local Plan Consultation 2016. Some elements of the full response such as formatting and images may not appear accurately. Should you wish to review the original response, please contact the Planning Policy team: [email protected] Survey Response: 1. Do you agree with the overall vision that the Draft Plan sets out for Epping Forest District? Strongly disagree Please explain your choice in Question 1: These plans for Chipping Ongar will decimate this historical town. As for the Greensted Road proposed development we can't understand why the historical Parish of Greensted is sited for proposed development for the following reasons: 1. Parish of the oldest wooden church in the world. How long will it take until we have takeaways next to the church? 2. This parish needs to be preserved for generations to come. 3. Fairfield Road supports approx. 180 homes, it can't take another 160. 4. Greensted Road has no clear point of entry for this development, this would be an accident waiting to happen. 5. We as land owners were NEVER asked if we wanted houses built in our gardens! 2. Do you agree with the overall vision that the Draft Plan sets out for Epping Forest District? Strongly disagree Please explain your choice in Question 2: SR-3090 Greensted Road development is Green Belt. -

Church of Norway Pre

You are welcome in the Church of Norway! Contact Church of Norway General Synod Church of Norway National Council Church of Norway Council on Ecumenical and International Relations Church of Norway Sami Council Church of Norway Bishops’ Conference Address: Rådhusgata 1-3, Oslo P.O. Box 799 Sentrum, N-0106 Oslo, Norway Telephone: +47 23 08 12 00 E: [email protected] W: kirken.no/english Issued by the Church of Norway National Council, Communication dept. P.O. Box 799 Sentrum, N-0106 Oslo, Norway. (2016) The Church of Norway has been a folk church comprising the majority of the popu- lation for a thousand years. It has belonged to the Evangelical Lutheran branch of the Christian church since the sixteenth century. 73% of Norway`s population holds member- ship in the Church of Norway. Inclusive Church inclusive, open, confessing, an important part in the 1537. At that time, Norway Church of Norway wel- missional and serving folk country’s Christianiza- and Denmark were united, comes all people in the church – bringing the good tion, and political interests and the Lutheran confes- country to join the church news from Jesus Christ to were an undeniable part sion was introduced by the and attend its services. In all people. of their endeavor, along Danish king, Christian III. order to become a member with the spiritual. King Olav In a certain sense, the you need to be baptized (if 1000 years of Haraldsson, and his death Church of Norway has you have not been bap- Christianity in Norway at the Battle of Stiklestad been a “state church” tized previously) and hold The Christian faith came (north of Nidaros, now since that time, although a permanent residence to Norway in the ninth Trondheim) in 1030, played this designation fits best permit. -

Taosrewrite FINAL New Title Cover

Authenticity and Architecture Representation and Reconstruction in Context Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Ruth First zaal van de Universiteit op maandag 10 november 2014 om 10.15 uur door Robert Curtis Anderson geboren op 5 april 1966 te Brooklyn, New York, USA Promotores: prof. dr. K. Gergen prof. dr. A. de Ruijter Overige leden van de Promotiecommissie: prof. dr. V. Aebischer prof. dr. E. Todorova dr. J. Lannamann dr. J. Storch 2 Robert Curtis Anderson Authenticity and Architecture Representation and Reconstruction in Context 3 Cover Images (top to bottom): Fantoft Stave Church, Bergen, Norway photo by author Ise Shrine Secondary Building, Ise-shi, Japan photo by author King Håkon’s Hall, Bergen, Norway photo by author Kazan Cathedral, Moscow, Russia photo by author Walter Gropius House, Lincoln, Massachusetts, US photo by Mark Cohn, taken from: UPenn Almanac, www.upenn.edu/almanac/volumes 4 Table of Contents Abstract Preface 1 Grand Narratives and Authenticity 2 The Social Construction of Architecture 3 Authenticity, Memory, and Truth 4 Cultural Tourism, Conservation Practices, and Authenticity 5 Authenticity, Appropriation, Copies, and Replicas 6 Authenticity Reconstructed: the Fantoft Stave Church, Bergen, Norway 7 Renewed Authenticity: the Ise Shrines (Geku and Naiku), Ise-shi, Japan 8 Concluding Discussion Appendix I, II, and III I: The Venice Charter, 1964 II: The Nara Document on Authenticity, 1994 III: Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, 2003 Bibliography Acknowledgments 5 6 Abstract Architecture is about aging well, about precision and authenticity.1 - Annabelle Selldorf, architect Throughout human history, due to war, violence, natural catastrophes, deterioration, weathering, social mores, and neglect, the cultural meanings of various architectural structures have been altered. -

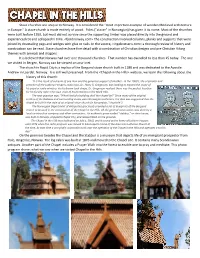

Stave Churches Are Unique to Norway. It Is Considered the "Most Important Example of Wooden Medieval Architecture in Europe." a Stave Church Is Made Entirely of Wood

Stave churches are unique to Norway. It is considered the "most important example of wooden Medieval architecture in Europe." A stave church is made entirely of wood. Poles ("staver" in Norwegian) has given it its name. Most of the churches were built before 1350, but most did not survive since the supporting timber was placed directly into the ground and experienced rot and collapsed in time. <fjordnorway.com> The construction involved columns, planks and supports that were joined by dovetailing pegs and wedges with glue or nails. In the source, <ingebretsens.com> a thorough review of history and construction can be read. Stave churches have fine detail with a combination of Christian designs and pre‐Christian Viking themes with animals and dragons. It is believed that Norway had over one thousand churches. That number has dwindled to less than 25 today. The one we visited in Bergen, Norway can be viewed on acuri.net. The church in Rapid City is a replica of the Borgund stave church built in 1180 and was dedicated to the Apostle Andrew in Laerdal, Norway. It is still well preserved. From the <Chapel‐in the‐Hills> website, we learn the following about the history of this church: "It is the result of a dream of one man and the generous support of another...In the 1960's, the originator and preacher of the Lutheran Vespers radio hour, Dr. Harry R. Gregerson, was looking to expand the scope of his popular radio ministry. As his dream took shape, Dr. Gregerson realized there was the perfect location for his facility right in his own state of South Dakota in the Black Hills. -

The Jacobson Family from Laerdal Parish, Sogn Og Fjordane County, Norway; Pioneer Norwegian Settlers in Greenwood Township, Vernon County, Wisconsin

THE JACOBSON FAMILY FROM LAERDAL PARISH, SOGN OG FJORDANE COUNTY, NORWAY PIONEER NORWEGIAN SETTLERS IN GREENWOOD TOWNSHIP, VERNON COUNTY, WISCONSIN BY LAWRENCE W. ONSAGER THE LEMONWEIR VALLEY PRESS Mauston, Wisconsin and Berrien Springs, Michigan 2018 COPYRIGHT © 2018 by Lawrence W. Onsager All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form, including electronic or mechanical means, information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author. Manufactured in the United States of America. -----------------------------------Cataloging in Publication Data----------------------------------- Onsager, Lawrence William, 1944- The Jacobson Family from Laerdal Parish, Sogn og Fjordane County, Norway; Pioneer Norwegian Settlers in Greenwood Township, Vernon County, Wisconsin. Mauston, Wisconsin and Berrien Springs, Michigan: The Lemonweir Valley Press, 2018. 1. Greenwood Township, Vernon County, Wisconsin 2. Jacobson Family 3. Laerdal Township, Sogn og Fjordane County, Norway 4. Greenwood Norwegian-American Settlement in Vernon County, Wisconsin I. Title Tradition claims that the Lemonweir River was named for a dream. Prior to the War of 1812, an Indian runner was dispatched with a war belt of wampum with a request for the Dakotas and Chippewas to meet at the big bend of the Wisconsin River (Portage). While camped on the banks of the Lemonweir, the runner dreamed that he had lost his belt of wampum at his last sleeping place. On waking in the morning, he found his dream to be a reality and he hastened back to retrieve the belt. During the 1820's, the French-Canadian fur traders called the river, La memoire - the memory. The Lemonweir rises in the extensive swamps and marshes in Monroe County. -

2015/2016 Welcome to the Sognefjord – All Year!

2015/2016 www.sognefjord.no Welcome to the Sognefjord – all year! The Sognefjord – Fjord Norways longest and most spectacular fjord with the Flåm railway, Jostedalen glacier, Jotunheimen national park, UNESCO Urnes stave church, local food, Aurlandsdalen valley, UNESCO fjord cruise, kayaking, glacier center, RIB-tours, hiking trails and other activities and accommodations with a fjord view. Motorikpark, deer farm, bathing facilities, fjord kayaking, family glacier hiking, museums, centers, playland and much more for the kids. The UNESCO Nærøyfjord was in 2004 titled by the National Geographic as “the worlds best unspoiled destination”. The Jotunheimen National park has fantastic hiking areas and Vettifossen - the most beautiful waterfall in Norway. There are marked hiking trails in Aurlandsdalen Valley and many other places around the Sognefjord. Glacier hiking at the Jostedalen glacier – the largest glacier on main land Europe – is an unique experience. There is Molden, Luster - © Terje Rakke, Nordic Life AS, Fjord Norway also three National tourist routes in the area – Sognefjellet, Aurlandsfjellet (“the Snowroad”) and Gaularfjellet, with attractions such as the viewpoints Stegastein and “Utsikten”. Summertime offers classic fjord experiences. In the autumn the air is clear and the fjord is Contents Contact us Tourist information dressed in beautiful autumn colors – the best time of the year for hiking and cycling. The Autumn and Winter 6 Visit Sognefjord AS Common phone (+47) 99 23 15 00 autumns shifts to the “Winter Fjord” with magical fjord light, alpine ski touring, snow shoe Sognefjord 8 Fosshaugane Campus Aurland: (+47) 91 79 41 64 walks, ski resorts, cross country skiing, fjord kayaking, RIB-safari, fjord cruises, the Flåm railway National Tourist Routes 12 Trolladalen 30 Flåm: (+47) 95 43 04 14 and guided tours to the magical blue ice caves under the glacier. -

Download the 2020 Scandinavia Travel Brochure

SCANDINAVIA 2020 TRAVEL BROCHURE BREKKE TOURS YOUR SCANDINAVIAN SPECIALIST SINCE 1956 Brekke Tours invites you to share our love of travel and join us to our own favorite corner of the world, Scandinavia! Brekke's 2020 escorted tours and independent travel options include a variety of activities and destinations across Scandinavia and beyond. It is our goal to make your travel dreams a reality while introducing you to breathtaking sites of natural beauty as well as the rich culture and history of the different countries in Scandinavia. Whether you choose to explore modern cities and quaint fjord-side villages on one of our escorted tours, travel independently to the mesmerizing Lofoten Islands or connect with your ancestors by visiting your family heritage sites, the staff of Brekke Tours is happy to help you create the perfect travel plan for you, your family and friends. Char Chaalse Linda Beth Molly Amanda Natalie Joey Diane WHY TRAVEL WITH BREKKE TOURS? Let our clients tell you why... “This was an amazing experience. The travel arrangements were so easy. Brekke Travel is #1. The Iceland extension that we did was also very good. The arrangements were wonderful. Thank you, Brekke Travel.” ~ E.J., Fergus Falls, MN “Brekke Tours was so professional and yet so personable to answer questions. The accommodations were excellent = A+. Tour guide was wonderful – fun and knowledgeable.” ~ G.L. and D.L., Choteau, MT “Got to see and do so much couldn’t have done on your own. Loved it all!” ~ 2019 Tour Participant “This was the trip of a lifetime and we enjoyed every moment.