The Unity of the Book of Isaiah As It Is Reflected in the New Testament Writings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

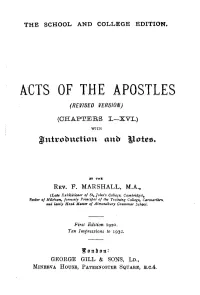

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

The Just Queen Saint Helen

“12 But before all these, they shall lay their hands on you, and persecute you, delivering you up to the synagogues, and into prisons, being brought before kings and rulers for my name's sake. 13 And it shall turn to you for a testimony. Settle it therefore in your hearts, not to meditate before what ye shall answer: For I will give you a mouth and wisdom, which all your adversaries shall not be able to gainsay nor resist. And ye shall be betrayed both by parents, and brethren, and kinsfolks, and friends; and some of you shall they cause to be put to death. And ye shall be hated of all men for my name's sake. But there shall not an hair of your head perish. In your patience possess ye your souls. ” ( Luk 21: 12-19) . This Newsletter is a free monthly publication of the Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, PO Box 256 Howell, NJ 07731, under the supervision of the priests of St. Mary Coptic Orthodox Church, East Brunswick, N.J. The committee welcomes your participation in the form of articles, reviews, news or comments. Please mail your articles, comments...etc. to the church or e-mail them to [email protected] If you would like this newsletter mailed to a friend or would like your name to be deleted from our mailing list, please email your request or fax it to (732) 821-1512. HALLOWEEN: HALLOWED OR HARMFUL ??? By His Grace Bishop Suriel The subject of Halloween is something that has caught my attention over the last few weeks. -

INDEX (1) Alphabetical

INDEX (1) Alphabetical Name Occasion Date Page Abraam Bishop of Repose 3 Paone 190 Fayoum Anna mother of the Repose 11 Hathor 68 Virgin Anna mother of the The conception of the Virgin Mary 13 Koiak 68 Virgin Anthony the Great Repose 22 Tobi 143 Anthony the Great Consecration of the church 4 Mesori 143 Apa Cyrus and John Martyrdom 6 Meshir 152 Apa Cyrus and John Transfer of Relics 4 Epip 152 Apa Iskiron of Kellin Martyrdom 7 Paone 193 Apa Noub Martyrdom 24 Epip 222 Apollo and Epip Repose of Apollo 5 Meshir 58 Apollo and Epip Repose of Epip 25 Paopi 58 Athanasius the Commemoration of the great sign 30 Thout 181 Apostolic, the 20th which the Lord did for him Patriarch Athanasius the Repose 7 Pashons 181 Apostolic Barbara Consecration of the church 8 Mesori 105 Barbara and Juliana Martyrdom 8 Koiak 105 Basilidis Martyrdom 11 Thout 36 Clement of Rome Martyrdom 29 Hathor 102 Cosmas and Damian Martyrdom 22 Hathor 89 Cosmas and Damian Consecration of the church 30 Hathor 89 Cyprian and Justina Martyrdom 21 Thout 39 Cyril VI, the 116th Repose 30 Meshir 162 Patriarch of Alexandria Demiana Martyrdom 13 Tobi 136 Demiana Consecration of the church 12 Pashons 136 Dioscorus, the 25th Repose 7 Thout 34 Patriarch of Alexandria 258 Name Occasion Date Page Gabriel, Archangel Commemoration 13 Hathor 77 Gabriel, Archangel Commemoration, Consecration of 22 Koiak 77 the church George of Alexandria Martyrdom 7 Hathor 64 George of martyrdom 23 Pharmouthi 173 Cappadocia George of Consecration of the first church 7 Hathor 173 Cappadocia George of Building the first -

![The Prophetic Concept of [Tsedaqah]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3592/the-prophetic-concept-of-tsedaqah-5413592.webp)

The Prophetic Concept of [Tsedaqah]

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 1953 The Prophetic Concept of [tsedaqah] Loren E. Arnett Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Arnett, Loren E., "The Prophetic Concept of [tsedaqah]" (1953). Graduate Thesis Collection. 421. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/421 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (This certification-sheet is to be bound with the thesis. The major pro fessor should have it filled out at the oral examination.) Name of candidate: ... h..~......... E ... :...... B.. r..~................ Oral examination : ---u . ;;i (Y (_- Date ............ .J. ... t... p.~ .............. :b .. :-' .... l..~.~ .. 3 ................. Committee: ....... .l~.~ .... £,,.u ....... ~--c ... -~~ ....... , Chairman .... L~ ..... ~:...... Z&.¢ ................................ --1 (\,__ / . • - \ ~\.?~' . \ ,_ • (JJJJ ~..,;) -__ •••••• a;:;:;r.-••••••••••••••••••••••;-.'••··················J ....................................... i // ,j Thesis title: ... ~~ ..... Pw..~ .. i ..... ~.~ .... e.JS, ..... 2?. .. f.... ~.:?. ................................................ Thesis approved in -

Archdiocese of St. Louis Office of Sacred Worship Lectio Divina Bible the Book of Isaiah

Archdiocese of St. Louis Office of Sacred Worship Lectio Divina Bible The Book of Isaiah The principal divisions of the Book of Isaiah are the following: I. Isaiah 1–39 II. Indictment of Israel and Judah (1:1–5:30) III. The Book of Emmanuel (6:1–12:6) IV. Oracles against the Foreign Nations (13:1–23:18) V. Apocalypse of Isaiah (24:1–27:13) VI. The Lord Alone, Israel’s and Judah’s Salvation (28:1–33:24) VII. The Lord, Zion’s Avenger (34:1–35:10) VIII. Historical Appendix (36:1–39:8) IX. Isaiah 40–55 X. The Lord’s Glory in Israel’s Liberation (40:1–48:22) XI. Expiation of Sin, Spiritual Liberation of Israel (49:1–55:13) XII. Isaiah 56–66 * * * Lectio Divina Read the following passage four times. The first reading, simple read the scripture and pause for a minute. Listen to the passage with the ear of the heart. Don’t get distracted by intellectual types of questions about the passage. Just listen to what the passage is saying to you, right now. The second reading, look for a key word or phrase that draws your attention. Notice if any phrase, sentence or word stands out and gently begin to repeat it to yourself, allowing it to touch you deeply. No elaboration. In a group setting, you can share that word/phrase or simply pass. The third reading, pause for 2-3 minutes reflecting on “Where does the content of this reading touch my life today?” Notice what thoughts, feelings, and reflections arise within you. -

The Doctrine of the Two-Natures of Christ CHAPTER 1

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Western Evangelical Seminary Theses Western Evangelical Seminary 1-1-1992 The oD ctrine of the Two-Natures of Christ: A Historical and Critical Analysis Amos Yong THE DOC TRINE OF THE TWO-NATURES OF CHRIST: A HI STORICAL AND CRI TI CAL ANALYSIS by Am os Yong A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requ irements of the degree of Master of Arts in the Division of Chr ist ian History and Th ought Western Evange lical Seminary October 1992 MURDOCK LEARNING RESOURCE CENTER GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY NEWBERG, OR 97132 @ 1992 Amo s Yong ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS page Acknowledgments . v Preface . vi Introduction viii Part One : The Hi storical Development of the Doctrine of the Two-Natures of Christ 1. Th e New Testament and the Person of Christ 2 Th e Deve lopment of New Testament Christology 3 Johannine Christology and the Incarnation 7 2. From the Apostolic Age to the First Council of Constantinople (381) ..... 13 Second Century Christologies 13 Te rtu llian and the Monarchian Controversies . 16 The Development of Alexandrian Christology . 20 Chr istology from Nicea to Constantinople 25 3. Christ as "Logos-Anthropos" . 32 Antecedents to the "Logos-Anthropos" Christology 33 Theodore of Mopsuestia and the Antiochene School 35 The Christology of Nestorius 39 4. The Road to Chalcedon . 46 The Nestorian-Cyril lian Debates . 46 From the Council of Ephesus to the "Robber Synod" 51 The Counc il of Chalcedon 53 iii 5. The Defense of the Chalcedonian Creed . 60 The Monophysite Re je ction of Chalcedon 61 The Triumph of Orthodox Christology . -

THE DEVELOPMENT of JEWISH IDEAS of ANGELS: EGYPTIAN and HELLENISTIC CONNECTIONS Ca

THE DEVELOPMENT OF JEWISH IDEAS OF ANGELS: EGYPTIAN AND HELLENISTIC CONNECTIONS ca. 600 BCE TO ca. 200 CE. Annette Henrietta Margaretha Evans Dissertation Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Stellenbosch Promotor: Prof. J. Cook Co-promotor: Prof. J. C. Thom March 2007 DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare that the work contained in this dissertation is my own original work and has not previously in its entirety or in part been submitted at any university for a degree. Signature Date (Annette Henrietta Margaretha Evans) i ABSTRACT This dissertation sets out to test the hypothesis that Egyptian and Hellenistic connections to Jewish beliefs about the functioning of angels facilitated the reception of Christianity. The method of investigation involved a close reading, combined with a History of Religions methodology, of certain texts with marked angelological content. The presence of certain motifs, especially “throne” and “sun/fire”, which were identified as characteristic of angelic functioning, were compared across the entire spectrum of texts. In this way the diachronic development of major angelological motifs became apparent, and the synchronic connections between the respective cultural contexts became noticeable. The course the research followed is reflected in the list of Contents. Ancient Egyptian myth and ritual associated with solar worship, together with Divine Council imagery, provides a pattern of mediation between heaven and earth via two crucial religious concepts which underly Jewish beliefs about the functioning of angels: 1) the concept of a supreme God as the king of the Gods as reflected in Divine Council imagery, and 2) the unique Egyptian institution of the king as the divine son of god (also related to the supremacy of the sun god). -

The Synodical Letter from Severus to John of Alexandria

Youhanna Nessim Youssef Melbourne, Australia [email protected] THE SYNODICAL LETTER FROM SEVERUS TO JOHN OF ALEXANDRIA Introduction Le ers are one of the most important sources of the life of Severus of Antioch.1 Synodical Le ers are those wri en by a patriarch soon a er his consecration, conveying the news of his election by the Synod which presided over it. The purpose of these instruments of ecclesial communion was to prove the orthodoxy of the writers. They contain a profession of faith, a statement by the new Patriarch, etc.2 In his monu- mental study, J. M. Fiey highlights the importance of the Synodical Le ers between the Patriarchs of Alexandria and Antioch especially starting at the time of Severus of Antioch.3 A er the election of Dioscorus II as new Patriarch, he wrote to Severus and received from him a reply (515–517).4 It seems that Timo- thy III5 (517–535) did not write a Synodical Le er to Severus, since Severus was hiding. However, according to the History of the Patriarchs6 and the Synaxarium7, he welcomed Severus while exiled and escaping (1) P. Allen and C. T. R. Hayward, Severus of Antioch (London―New York, 2004) 4. (2) P. Allen, Sophronius of Jerusalem and Seventh-Century Heresy. The Synodical Le er and Other Documents. Introduction, Texts, Translation and Com- mentary (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2009) (Oxford Early Christian Texts) 47–48. (3) J. M. Fiey, Coptes et Syriaques, contacts et échanges, Studia Orientalia Christiana Collectanea 15 (1972–1973) 295–366 and esp. -

Foxe's Book of Martyrs

FOXE'S BOOK OF MARTYRS CHAPTER I - History of Christian Martyrs to the First General Persecutions Under Nero Christ our Savior, in the Gospel of St. Matthew, hearing the confession of Simon Peter, who, first of all other, openly acknowledged Him to be the Son of God, and perceiving the secret hand of His Father therein, called him (alluding to his name) a rock, upon which rock He would build His Church so strong that the gates of hell should not prevail against it. In which words three things are to be noted: First, that Christ will have a Church in this world. Secondly, that the same Church should mightily be impugned, not only by the world, but also by the uttermost strength and powers of all hell. And, thirdly, that the same Church, notwithstanding the uttermost of the devil and all his malice, should continue. Which prophecy of Christ we see wonderfully to be verified, insomuch that the whole course of the Church to this day may seem nothing else but a verifying of the said prophecy. First, that Christ hath set up a Church, needeth no declaration. Secondly, what force of princes, kings, monarchs, governors, and rulers of this world, with their subjects, publicly and privately, with all their strength and cunning, have bent themselves against this Church! And, thirdly, how the said Church, all this notwithstanding, hath yet endured and holden its own! What storms and tempests it hath overpast, wondrous it is to behold: for the more evident declaration whereof, I have addressed this present history, to the end, first, that the wonderful works of God in His Church might appear to His glory; also that, the continuance and proceedings of the Church, from time to time, being set forth, more knowledge and experience may redound thereby, to the profit of the reader and edification of Christian faith. -

Thesis Final

Anxious Origins: Zora Neale Hurston and the Global South, 1927-1942 By Dana Badley III Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson: Dr. Doreen Fowler ________________________________ Dr. Giselle Anatol ________________________________ Dr. Cheryl Lester Date Defended: March 26, 2014 ii The Thesis Committee for Dana Badley III certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Anxious Origins: Zora Neale Hurston and the Global South, 1927-1942 ________________________________ Chairperson: Dr. Doreen Fowler Date approved: March 26, 2014 iii ABSTRACT Zora Neale Hurston’s autoethnographic trilogy of the Global South – Mules and Men (1935), Tell My Horse (1938), and Dust Tracks on a Road (1942) – charts a geocultural terrain that recovers transgressive histories otherwise erased from public historical discourse. The medium is the message: penned in dialect obscuring the subversive “inside meanin’ of words,” her folklore collections split the historical archive wide open by incorporating the lives and deaths of “unreal” bodies into a preexisting narrative of Southern subjugation. These politically subversive tales of agency and resistance enact a dynamic, malleable, intergenerational mode of oral history that suggests the unfinished work of mourning for that which is no longer there. Trained as an anthropologist at Columbia University yet distrustful of the profession’s intentions, Hurston confronts her own ambivalence towards the ethnographic archive throughout her career dedicated to (re)tracing these anxious origins, prefigured as both genetically specific and racially mythologized, across a region beset by a politics of racialized loss. -

EGYPTIANS in IRELAND: a QUESTION of COPTIC PEREGRINATIONS by Robert K

EGYPTIANS IN IRELAND: A QUESTION OF COPTIC PEREGRINATIONS by Robert K. Ritner, Jr. The onedutv we oue to hi~torvIS to rewr~te~t Oscar Wllde Tile Ctrirc a\ At tr,~ The Book of Antiphons of the Monastery of Bangor, Ireland, contains a poem about the monastery regimen of which the following quotation is a part: Domus dcllci~~pIena Super petram constructs Necnonvlnea Vera Ex Aegvpto transducta . I The home to which the poem refers is, of course, the monastic organiza- tion itself, born on Egyptian soil in the fourth century, and eventually spreading throughout the West. But nowhere did it attain such pervasive importance as in Ireland. Maire and Liam de Paor note the presence of Egyptian-oriented monasticism in the British Isles during the fifth century,' and such monastic communities were encountered by both Patrick in the fifth century and Augusrine of Canterbury in 597, in Ireland and England respectively. Similar communities continued to exist in Britain as a tradition in opposition to Roman authority, and Bede makes frequent references to their non-Catholic practices.7 In Ireland, however, in contrast to the Western diocesan system, monasticism provided the main organhation of the Church. Church leaders, moreover, were selected from among the monks themselves, a practice which lasted at least until the twelfth-century arrival of the chronicler Giraldus Cambrensis with the invading Normans. The close similarity to the structure of the Coptic Church-monastically oriented in form and leadership-as well as the early and somewhat myste- rious spread of Christianity into the British Isles, has led many to postulate factors of Coptic influence, if not direct participation by Coptic mission- aries. -

The Church of Armenia

• • ' THE CHURCH OF ARMENIA HER HISTORY, DOCTRINE, RULE, DISCIPLINE LITURGY, LITERATURE, AND EXISTING CONDITION BY MALACHIA ORMANIAN FORMERLY ARIIENIAN PATRIARCH OF CONSTANTINOPLE TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH EDITION WITH THE AUTHOR'S PERMISSION BY G. MARCAR GREGORY, V.D. REVENUE SERVICE, BENGAL, INDIA {RETIRED) LIEUT,•COLONEL, INDIAN VOLUNTEER FORCE. WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY THE RIGHT REV. J. E. C. WELLDON, D.D. A. R. MOWBRAY & CO., LTD. LoNDON: 28 Margaret Street, Oxford Circus, W. OxroRD: 9 High Street INTRODUCTION BY BISHOP WELLDON THE task of writing an Introduction to Mr. Gregory's translation of Mgr. Ormanian's book upon the Church of Armenia is not free from difficulty ; nor is it made the less difficult because the Bishop who should have written it, had his life been spared, was a man of such wide and various learning as the late Bishop of Salisbury, Dr. Wordsworth. Yet in that Church there is much that is interesting to all Christians, and perhaps especially to members of the Church of England. For the history of the Church of Armenia is a witness to certain great principles of ecclesiastical life. It is a protest against the assumed infallibility and universality of the Church of Rome. For the Church of Armenia believes that "no Church, however great in herself, represents the whole of Christendom ; that each one, taken singly, can be mistaken, and to the Universal Church alone belongs the privilege of infallibility in her dogmatic decisions." * She takes her stand then upon the national character and prerogative of Churches. She holds, as the Church of England holds, that it is a fraternity of Churches tracing their pedigree backwards to an Apostolical origin, developing themselves on separate lines, yet knit together by a common creed and by spiritual union with the same • Preface to the French Edition, p.