The Prophetic Concept of [Tsedaqah]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sermons on the Old Testament of the Bible by Jesus of Nazareth

Sermons on the Old Testament of the Bible by Jesus of Nazareth THROUGH DR. DANIEL G. SAMUELS This online version published by Divine Truth, USA http://www.divinetruth.com/ version 1.0 Introduction to the Online Edition For those already familiar with the messages received through James Padgett , the Samuels channelings are a blessing in that they provide continuity and integration between the teachings of the Bible and the revelations received through Mr. Padgett. Samuels’ mediumship differed from Padgett’s in that it is much more filled with detail and subtlety, which makes it a perfect supplement to the “broad strokes” that Padgett’s mediumship painted with. However, with this greater resolution of detail comes greater risk of error, and it is true that we have found factual as well as conceptual errors in some of Samuel’s writings. There are also a number of passages where the wording is perhaps not as clear as we would have wished – where it appears that there was something of a “tug-of-war” going on between Samuels’ and Jesus’ mind. In upcoming editions we will attempt to notate these passages, but for now the reader is advised (as always) to read these messages with a prayerful heart, asking that their Celestial guides assist them in understanding the true intended meaning of these passages. The following is an excerpt from a message received from Jesus regarding the accuracy and clarity of Dr. Samuels’ mediumship: Received through KS 6-10-92 I am here now to write...and we are working with what is known as a "catch 22" on earth at this time, which means that it's very difficult to convince someone about the accuracy and clarity of a medium -through the use of mediumistic means. -

Three Commands from Isaiah 54

Three commands from Isaiah 54 Brynmawr Family Church Sermon Stuart Wheatman, Sunday 24th June 2012 Intro- • Promise for us that God will enlarge us. We are to get ready because God is moving. God will again revive His people here in Wales. • Isaiah ministered into the depression caused by the Assyrian invasion- Israel went into captivity first and then Judah followed when the Babylonians invaded. However, Isaiah's message is that a REMNANT will be left, just like a stump is left when a tree is cut down. The Assyrians cut down the trees and decimated the land. However God would take the stump, the remnant that is left of Israel, and make it grow, make it fruitful, multiplying their numbers. Even when God's people have been through tough times there is a promise of fruitfulness. • Prophetic foreshortening- Isaiah, as the other prophets, sees the future like a series of mountains in the distance- some near, others far away. He describes what he sees as if they blur into one- some of it refers to the more distant future, some to their immediate situation. Isaiah 53 precedes this chapter, it is perhaps the most detailed of all the Old Testament predictions of what Jesus would achieve on the cross. God's people's fruitfulness ultimately comes from the victory of the Gospel. Read Isaiah 54:1-6 'SING'- v1 'Sing O barren' • The opposite of what you would expect! In the middle eastern culture of the day the ability to have children was hugely important to them. • Paradox of faith. -

Isaiah 56-66

ISAIAH 56-66 209 Introduction Introduction to Isaiah 56-66 With chapter 56 we are moving into a different world. The School of prophet-preachers who composed Isaiah 40-55 wrote during the time of the Babylonian Exile. They kept insisting that YHWH would bring the exile to an end and restore Judah and Jerusalem. In the early part of their ministry (see chapters 40-48), they directed the people’s hopes towards the Persian king, Cyrus, whom they described as YHWH’s chosen instrument. They were partly right in that in 539 Cyrus entered Babylon in triumph, and continued his policy of allowing peoples who had been deported to Babylon to return to their homelands. This included the exiles from Judah (see Ezra 6:3ff). A small group of exiles led by Sheshbazzar returned to Judah (see Ezra 1:5-11; 5:13-15; 1 Chronicles 3:18). The foundations of the Temple were laid, but the work was not continued (see Ezra 5:16). It appears from chapters 49-55 that they lost hope in Cyrus, but not in YHWH. They kept faithful to their mission of keeping YHWH’s promise before the attention of the people. Perhaps they never had much of a hearing, but in the second section (49-55) it is clear that they were scoffed at and rejected. However, they continued to trust that YHWH was, indeed, speaking through them. Cyrus was killed in battle in 530. His successor, Cambyses was succeeded in 522 by Darius I. This was an unsettled period, with revolutions breaking out throughout the empire. -

MEANINGLESS WORSHIP Bible Background • Isaiah 29 Printed Text • Isaiah 29:9-16A | Devotional Reading • Luke 8:9-14

June 16 • BIBLE STUDY GUIDE 3 MEANINGLESS WORSHIP Bible Background • Isaiah 29 Printed Text • Isaiah 29:9-16a | Devotional Reading • Luke 8:9-14 Aim for Change By the end of the lesson, we will: KNOW that God expects worship from the heart; UNDERSTAND that God is worthy to be praised; and PRAISE God from the heart. In Focus Have you ever heard the old English idiom about the person who can’t see the forest for the trees? This proverb generally describes a person who gets so caught up in the details of a situation or life itself that he or she fails to see the complete picture. Details serve as distractions that cause us to focus our attention on the smaller, less important things in life rather than living life to its fullest. This idiom can also apply to our relationship with God. It is so easy to get caught up in the daily burdens and blessings of life that we forget about the Life Giver. We fail to consult God about our daily decisions or even spend time with Him on a daily basis. Then, even though we faithfully attend church, our worship can become hollow. We lift our voices and sing songs without meaning, we say “Amen” to teachings we have no intention of honoring, and we fulfill our religious regulations without any thought to our righteous relationship. Today’s lesson focuses on the nation of Judea during a time when the nation’s prosperity and the people’s pleasures caused them to forget about God and serves as a reminder that God is always to be worshiped in spirit and in truth. -

A Study of Paul's Interpretation of the Old Testament with Particular Reference to His Use of Isaiah in the Letter to the Romans James A

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Western Evangelical Seminary Theses Western Evangelical Seminary 5-1-1959 A Study of Paul's Interpretation of the Old Testament with Particular Reference to His Use of Isaiah in the Letter to the Romans James A. Field Recommended Citation Field, James A., "A Study of Paul's Interpretation of the Old Testament with Particular Reference to His Use of Isaiah in the Letter to the Romans" (1959). Western Evangelical Seminary Theses. 134. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/wes_theses/134 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Evangelical Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western Evangelical Seminary Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPROVED BY l'fajor Professor: ~~ • ..,e ~~ I Co-operat.ive Reader: ~ f. w~ Professor of Thesis Form: Gby~ A STUDY OF PAUL'S INTERPRETATIOl~ OF THE OLD TESTAHENT WITH PARTICULAR REFER.E.'NCE ro HIS USE OF ISAIAH IN THE LETTER TO THE ROMANS by James A. Field A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Western Evangelical Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Divinity Portland 22, Oregon May, 1959 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. DIJTRODUCTION., • • • • • • • • .. .. • • • • • • • • • . l A. Statement of the Problem. • • • • • • • • • ••••• l B. Statement of the Pu~pose.. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 4 c. Justification for the Study • • • • • • • • ••••• 4 D. Limitations of the Study. • • • • • • • • • ••••• 5 E. Statement of Procedure. • • • • • • • • • • • • ••• 6 II. HISTORICAL SURVEY OF LITERATURE ON THE l'iiDi'l TESTA1<IENT USE OF THE OLD 'l'ESTAl1ENT • • • • • • • • • • 7 A. -

The Eschatological Blessing (Hk'r"B.) of the Spirit in Isaiah: with Special Reference to Isaiah 44:1-5

DOI: https://doi.org/10.28977/jbtr.2016.10.39.307 The Eschatological Blessing (hk'r"B.) of the Spirit in Isaiah / YunGab Choi 307 The Eschatological Blessing (hk'r"B.) of the Spirit in Isaiah: with Special Reference to Isaiah 44:1-5 YunGab Choi* 1. Introduction The primary purpose of this paper is to explicate the identity of the “eschatological1) blessing (hk'r"B.) of the Spirit”2) in Isaiah 44:3. The Hebrew term — hk'r"B. — and its derivative form appear ten times (19:24, 25; 36:16; 44:3; *Ph. D in Old Testament at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Assistant Professor of Old Testament at Kosin University. [email protected]. 1) The English term “eschatology” comes from Greek word eschatos (“last”). Accordingly in a broad sense, “[e]schatology is generally held to be the doctrine of ‘the last things’, or of ‘the end of all things.’” (Jürgen Moltmann, The Coming of God: Christian Eschatology [Minneapolis: Fortress Press,1996], 1). In a similar vein, Willem A. VanGemeren defines eschatology as “biblical teaching which gives humans a perspective on their age and a framework for living in hope of a new age” (Willem A. VanGemeren, Interpreting the Prophetic Word: An Introduction to the Prophetic Literature of the Old Testament [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1990], 88). G. B. Caird defines eschatology as “the study of, or the corpus of beliefs held about, the destiny of man and of the world” (G. B. Caird, The Language and Imagery of the Bible [Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1980], 243). -

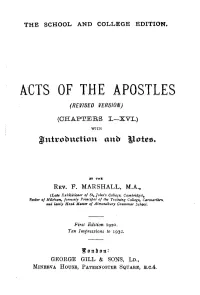

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

Romans 11:27-28 Romans 11:27-Paul Cites Isaiah 59:21, 27:9

Romans 11:27-28 Romans 11:27-Paul Cites Isaiah 59:21, 27:9 To Teach That There Will Be A National Regeneration Of Israel At Christ’s Second Advent In Romans 11:27, Paul cites Isaiah 59:21 and 27:9 to support his assertion that there will be a national regeneration of Israel, which will take place at Christ’s Second Advent. Romans 11:27, “THIS IS MY COVENANT WITH THEM, WHEN I TAKE AWAY THEIR SINS.’” In Romans 11:26, Paul cites Isaiah 59:20 to support his statement in Romans 11:26a that “ all Israel will be saved ,” which refers to the national regeneration of the nation of Israel at Christ’s Second Advent. Isaiah 59:20, “A Redeemer will come to Zion and to those who turn from transgression in Jacob,” declares the LORD. In Romans 11:27, Paul cites a combination of Isaiah 59:21 and 27:9 as further support for his prediction in Romans 11:26 that there will be a national regeneration of Israel. Isaiah 59:21, “As for Me, this is My covenant with them , says the LORD: ‘My Spirit which is upon you, and My words which I have put in your mouth shall not depart from your mouth, nor from the mouth of your offspring, nor from the mouth of your offspring's offspring,’ says the LORD, ‘from now and forever.’” Isaiah 27:9, “Therefore through this Jacob's iniquity will be forgiven; And this will be the full price of the pardoning of his sin : When he makes all the altar stones like pulverized chalk stones; When Asherim and incense altars will not stand.” Paul is quoting exactly from the first line of Septuagint translation of Isaiah 59:21, which is kaiV -

The Unity of the Book of Isaiah As It Is Reflected in the New Testament Writings

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Western Evangelical Seminary Theses Western Evangelical Seminary 4-1-1958 The nitU y of the Book of Isaiah as it is Reflected in the New Testament Writings Theodore F. Dockter Recommended Citation Dockter, Theodore F., "The nitU y of the Book of Isaiah as it is Reflected in the New Testament Writings" (1958). Western Evangelical Seminary Theses. 120. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/wes_theses/120 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Evangelical Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western Evangelical Seminary Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPROVED BY Major Professor: ~ ;-x ~ I Co-operative Reader: ;" L_i-- v t:;o_f- ,,,"Z( Professor of Thesis Form: ~.(. ~ THE UNITY OF THE BOOK OF ISAIAH AS IT IS REFLECTED :m THE NEW TES UMElJT iilUTINGS by Theodore F. Dockter A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the 'Westerr;._ Evangelical Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Bachelor of Divinity Portland 22, Oregon April, 1958 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHPJ'TER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • .. .. • • • • ...... " . 1 The Problem and Purpose of the Study • • • • • .. • • 2:. 2 Justification of this Study • • • • 6 .. .. • • • • Limitation of this Study • • .. • • 3 Assumptions. • • • • • • • • • •• 3 Definitions. • • • • • • • • • 3 Organization of the Study. • • • • • • • • • • • 4 II. THE CRITICAL AND Trul.DITIONAL VJ:'EliS REG.!\P..DING THE UNITY OF ISAIAH • • • • • • • • • • • • • 6 History of Criticism of Isaiah • . 7 Criticism of Isaiah • • • • • • • o • • •• . s Critical Arguments Concer~~ng Isaiah 36 - 39 •• • • lS Prophecy Concerning Cyrus. -

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons SONG OF SOLOMON JEREMIAH NEWEST ADDITIONS: Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 53 (Isaiah 52:13-53:12) - Bruce Hurt Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 35 - Bruce Hurt ISAIAH RESOURCES Commentaries, Sermons, Illustrations, Devotionals Click chart to enlarge Click chart to enlarge Chart from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission Another Isaiah Chart see on right side Caveat: Some of the commentaries below have "jettisoned" a literal approach to the interpretation of Scripture and have "replaced" Israel with the Church, effectively taking God's promises given to the literal nation of Israel and "transferring" them to the Church. Be a Berean Acts 17:11-note! ISAIAH ("Jehovah is Salvation") See Excellent Timeline for Isaiah - page 39 JEHOVAH'S JEHOVAH'S Judgment & Character Comfort & Redemption (Isaiah 1-39) (Isaiah 40-66) Uzziah Hezekiah's True Suffering Reigning Jotham Salvation & God Messiah Lord Ahaz Blessing 1-12 13-27 28-35 36-39 40-48 49-57 58-66 Prophecies Prophecies Warnings Historical Redemption Redemption Redemption Regarding Against & Promises Section Promised: Provided: Realized: Judah & the Nations Israel's Israel's Israel's Jerusalem Deliverance Deliverer Glorious Is 1:1-12:6 Future Prophetic Historic Messianic Holiness, Righteousness & Justice of Jehovah Grace, Compassion & Glory of Jehovah God's Government God's Grace "A throne" Is 6:1 "A Lamb" Is 53:7 Time 740-680BC OTHER BOOK CHARTS ON ISAIAH Interesting Facts About Isaiah Isaiah Chart The Book of Isaiah Isaiah Overview Chart by Charles Swindoll Visual Overview Introduction to Isaiah by Dr John MacArthur: Title, Author, Date, Background, Setting, Historical, Theological Themes, Interpretive Challenges, Outline by Chapter/Verse. -

Paul's Use of the Septuagint in Romans 9-11

PAUL’S USE OF THE SEPTUAGINT IN ROMANS 9-11 Timo Laato Master’s Thesis Greek Philology School of Languages and Translation Studies Faculty of Humanities University of Turku November 2018 The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. UNIVERSITY OF TURKU School of Languages and Translation Studies Faculty of Humanities TIMO LAATO: Paul’s Use of the Septuagint in Romans 9-11 Master’s Thesis, 84 pages Greek Philology November 2018 The undertaking of the present study is to examine Paul’s use of the Septuagint in Rom. 9-11, especially the guidelines which affect his interpretation of the Old Testament. At the outset, an overview of the content of his Epistle to the Romans is provided. Next, some relevant aspects of Paul’s general way of interpreting the Old Testament are presented and expanded. He repeatedly employs the “promise – fulfillment” scheme in his attempt to define more in-depth the relationship be- tween the Old and New Testament. Further, he often draws on typological Bible exposition, rendering the Old Testament accounts and events as a paradigm for the New Testament time span. The Pauline manner of interpreting the Old Testament achieves more precision and accuracy through a comprehensive exegesis of Rom. 9-11 which particularly relate to Israel and their Holy Scriptures. Here all Old Testament quotations (and many Old Testament allusions) are examined one by one. Where appropriate, the original context of the quotations is also observed. Paul cites recurrently, but not always the Septuagint (or possibly another Greek translation). -

Isaiah 59:1-13 Prayer

Isaiah 59:1-13 No: 17 Week:301 Wednesday 11/05/11 Prayer Dear Saviour, remind me of what You have done for me, again and again. Show me the bitterness of death You endured and the scars of sacrifice You bore for me, and if I am too proud to look on You, challenge me repeatedly, lest through ignorance self-centredness I lose my way. Give me the grace and humility, I pray, to look at You, my crucified Lord, and know You did it all for me. AMEN Prayer Suggestions (Offering alternatives that can broaden your experience of prayer) Prayer ideas Share your thoughts with someone close before praying. Sometimes the very act of saying something out loud to someone else can help to filter out the important from the unimportant, and the casual from the wise. On-going prayers Pray for the stability of the world. Pray for leaders of industries such as Google, Microsoft and Apple, whose products define our generation, and whose stability affects virtually all people Pray for the newspapers, whose headlines can significantly influence world and local affairs Give thanks to God for the benefits of His grace, which You have received. Meditation This is true praise of Almighty God; to respect His authority as Creator and Lord; to accept His grace as effective prior to faith; to discipline the soul to His Word and His will; to pursue His will with self-effacing vigour. to declare Him in the world by word and deed; to aspire to the high moral standards of Christ.