Stories of Words: Spanish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

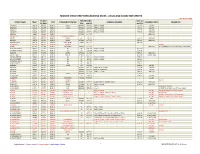

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

The Morgan's Role out West

THE MORGAN’S ROLE OUT WEST CELEBRATED AT VAQUERO HERITAGE DAYS 2012 By Brenda L. Tippin Stories of cowboys and the old west have always captivated Americans with their romance. The California vaquero was, in fact, America’s first cowboy and the Morgan horse was the first American breed regularly used by many of these early vaqueros. Renewed interest in the vaquero style of horsemanship in recent years has opened up huge new markets for breeders, trainers, and artisans, and the Morgan horse is stepping up to take his rightful place as an important part of California Vaquero Heritage. THE MORGAN CONNECTION and is becoming more widely recognized as what is known as the The Justin Morgan horse shared similar origins with the horses of “baroque” style horse, along with such breeds as the Andalusian, the Spanish conquistadors, who were the forefathers of the vaquero Lippizan, and Kiger Mustangs, which are all favored as being most traditions. The Conquistador horses, brought in by the Moors, like the horse of the Conquistadors. These breeds have the powerful, carried the blood of the ancient Barb, Arab, and Oriental horses— deep rounded body type; graceful arched necks set upright, coming the same predominant lines which may be found in the pedigree out of the top of the shoulder; and heavy manes and tails similar of Justin Morgan in Volume I of the Morgan Register. In recent to the European paintings of the Baroque period, which resemble years, the old style foundation Morgan has gained in popularity today’s original type Morgans to a remarkable degree. -

Foreign Consular Offices in the United States

United States Department of State Foreign Consular Offices in the United States Spring/Summer2011 STATE DEPARTMENT ADDRESSEE *IF YOU DO NOT WISH TO CONTINUE RECEIVING THIS PUBLICATION PLEASE WRITE CANCEL ON THE ADDRESS LABEL *IF WE ARE ADDRESSING YOU INCORRECTLY PLEASE INDICATE CORRECTIONS ON LABEL RETURN LABEL AND NAME OF PUBLICATION TO THE OFFICE OF PROTOCOL, DEPARTMENT OF STATE, WASHINGTON, D.C. 20520-1853 DEPARTMENT OF STATE PUBLICATION 11106 Revised May 24, 2011 ______________________________________________________________________________ For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 FOREIGN CONSULAR OFFICES IN THE UNITED STATES i PREFACE This publication contains a complete and official listing of the foreign consular offices in the United States, and recognized consular officers. Compiled by the U.S. Department of State, with the full cooperation of the foreign missions in Washington, it is offered as a convenience to organizations and persons who must deal with consular representatives of foreign governments. It has been designed with particular attention to the requirements of government agencies, state tax officials, international trade organizations, chambers of commerce, and judicial authorities who have a continuing need for handy access to this type of information. Trade with other regions of the world has become an increasingly vital element in the economy of the United States. The machinery of this essential commerce is complicated by numerous restrictions, license requirements, quotas, and other measures adopted by the individual countries. Since the regulations affecting both trade and travel are the particular province of the consular service of the nations involved, reliable information as to entrance requirements, consignment of goods, details of transshipment, and, in many instances, suggestions as to consumer needs and preferences may be obtained at the foreign consular offices throughout the United States. -

Doma Vaquero My Journey in Understanding Spanish Traditions

Written by Alice Trindle Copyright: T&T Horsemanship May 2006 No portion of this article can be reproduced without the consent of the author Doma Vaquero My Journey in Understanding By Alice Trindle Spanish Traditions appreciate in the Quarter Horse were originally t all started with a horse! Juandero was a I placed in the gene pool by the Spanish beautiful bay Azteca gelding. He didn’t just Andalusian. The conquistadors brought the appear at my place…He arrived! His presence Spanish blood horses into Mexico during the was unmistakably alive, somewhat full of himself, Aztec era, and later on they brought them into but aware of everything around him and quite what became the continental United States with prepared to play. As I had the honor to begin to Spanish missionaries, and the Spanish army. work with Juandero I soon discovered there was These horses were very agile and athletic, as their more to this picture then a beautiful horse, with a heritage was to fight the bulls of Spain. Even willing and playful attitude, that carried himself in today, these bulls are not your average polled a natural balance that was light and suspended. Hereford with a docile temperament! The Spanish There was a tradition – a heritage – that was bull is bred for attitude with horns, and therefore exhibiting itself in every movement of this horse your horse must be able to leg-yield or half-pass, and I wanted to know more about it. canter and counter-canter, in balance and at various speeds. In Spain, the Doma Vaquero uses a 13-foot long wood pole called the garrocha for working the bulls, as well as a partner in an elegant dance and artistic display between horse, rider, and pole, set to beautiful Spanish guitar music. -

Chapter 6: End of Spanish Rule

End of Spanish Rule Why It Matters Europeans had ruled the New World for centuries. In the late 1700s people in the Americas began to throw off European rule. The thirteen English colonies were first. The French colony of Haiti was next. Texas was one part of the grand story of the independence of the Spanish colonies. For the people living in Texas, though, the transition from Spanish province to a territory in the independent nation of Mexico was tremendously important. The Impact Today • Texas was the region of North America in which Spanish, French, English, and Native Americans met. • Contact among people encourages new ways of thinking. Later the number of groups in Texas increased as African and Asian people, as well as others from all over the world, brought their cultures. 1773 1760 ★ Spanish 1779 ★ Atascosito Road used for abandon East • Nacogdoches military purposes Texas missions founded 1760 1770 1780 1790 1763 1773 1789 • Treaty of Paris ended • Captain James Cook crossed • George Washington Seven Years’ War the Antarctic Circle became first president 1783 1793 • Great Britain and United • Eli Whitney States signed peace treaty invented the cotton gin 136 CHAPTER 6 End of Spanish Rule Summarizing Study Foldable Make this foldable and use it as a journal to help you record key facts about the time when Spain ruled Texas. Step 1 Stack four sheets of paper, one on top of the other. On the top sheet of paper, trace a large circle. Step 2 With the papers still stacked, cut out all four circles at the same time. -

Spanish Relations with the Apache Nations East of the Rio Grande

SPANISH RELATIONS WITH THE APACHE NATIONS EAST OF THE RIO GRANDE Jeffrey D. Carlisle, B.S., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2001 APPROVED: Donald Chipman, Major Professor William Kamman, Committee Member Richard Lowe, Committee Member Marilyn Morris, Committee Member F. Todd Smith, Committee Member Andy Schoolmaster, Committee Member Richard Golden, Chair of the Department of History C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Carlisle, Jeffrey D., Spanish Relations with the Apache Nations East of the Río Grande. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May 2001, 391 pp., bibliography, 206 titles. This dissertation is a study of the Eastern Apache nations and their struggle to survive with their culture intact against numerous enemies intent on destroying them. It is a synthesis of published secondary and primary materials, supported with archival materials, primarily from the Béxar Archives. The Apaches living on the plains have suffered from a lack of a good comprehensive study, even though they played an important role in hindering Spanish expansion in the American Southwest. When the Spanish first encountered the Apaches they were living peacefully on the plains, although they occasionally raided nearby tribes. When the Spanish began settling in the Southwest they changed the dynamics of the region by introducing horses. The Apaches quickly adopted the animals into their culture and used them to dominate their neighbors. Apache power declined in the eighteenth century when their Caddoan enemies acquired guns from the French, and the powerful Comanches gained access to horses and began invading northern Apache territory. -

Jose Maria Villamil: Soldier, Statesman of the Americas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 Jose Maria Villamil: Soldier, Statesman of the Americas. Daniel W. Burson Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Burson, Daniel W., "Jose Maria Villamil: Soldier, Statesman of the Americas." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3005. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3005 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Capital Finance Board Workshop EXHIBITS

Capital Finance Board Workshop EXHIBITS April 27, 2018 Exhibit List 2018 Board Capital Finance Workshop April 27, 2018 Pages 1 through 42, the Capital Finance Board Workshop Memo, can be found on the District’s website at: http://www.ebparks.org/meetings EXHIBIT LIST 1a: GRANTS AA – WW Acquisition Funding ........................................................................................ 43 1b: GRANTS AA – WW Development Funding .................................................................................... 53 2a: Active Projects – 2018 Budget ............................................................................................................. 71 2b: 2018 Active Projects by Department .................................................................................................. 87 3: Measure CC Status Report ................................................................................................................... 89 4a: Measure AA Unappropriated Funds .................................................................................................. 111 4b: Measure AA Consolidated Funds ....................................................................................................... 113 5a: Measure WW Appropriations as of April 5, 2018 ......................................................................... 115 5b: Measure WW Remaining Balances, Sorted by Park ...................................................................... 125 5c: Measure WW Status Report as of April 5, 2018 .......................................................................... -

Unit 3: Exploration and Early Colonization (Part 2)

Unit 3: Exploration and Early Colonization (Part 2) Spanish Colonial Era 1700-1821 For these notes – you write the slides with the red titles!!! Goals of the Spanish Mission System To control the borderlands Mission System Goal Goal Goal Represent Convert American Protect Borders Spanish govern- Indians there to ment there Catholicism Four types of Spanish settlements missions, presidios, towns, ranchos Spanish Settlement Four Major Types of Spanish Settlement: 1. Missions – Religious communities 2. Presidios – Military bases 3. Towns – Small villages with farmers and merchants 4. Ranchos - Ranches Mission System • Missions - Spain’s primary method of colonizing, were expected to be self-supporting. • The first missions were established in the El Paso area, then East Texas and finally in the San Antonio area. • Missions were used to convert the American Indians to the Catholic faith and make loyal subjects to Spain. Missions Missions Mission System • Presidios - To protect the missions, presidios were established. • A presidio is a military base. Soldiers in these bases were generally responsible for protecting several missions. Mission System • Towns – towns and settlements were built near the missions and colonists were brought in for colonies to grow and survive. • The first group of colonists to establish a community was the Canary Islanders in San Antonio (1730). Mission System • Ranches – ranching was more conducive to where missions and settlements were thriving (San Antonio). • Cattle were easier to raise and protect as compared to farming. Pueblo Revolt • In the late 1600’s, the Spanish began building missions just south of the Rio Grande. • They also built missions among the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico. -

Spain on the Plains

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Spain on the Plains Full Citation: James A Hanson, “Spain on the Plains,” Nebraska History 74 (1993): 2-21 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1993Spain.pdf Date: 8/13/2013 Article Summary: Spanish and Hispanic traditions have long influenced life on the Plains. The Spanish came seeking treasure and later tried to convert Indians and control New World territory and trade. They introduced horses to the Plains Indians. Hispanic people continue to move to Nebraska to work today. Cataloging Information: Names: Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, Fray Marcos de Niza, Esteban, the Turk, Juan de Padilla, Hernán de Soto, Juan de Oñate, Etienne de Bourgmont, Pedro de Villasur, Francisco Sistaca, Pierre and Paul Mallet; Hector Carondelet, James Mackay, John Evans, Pedro Vial, Juan Chalvert, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, -

Hotel Los Arcos De Sonora Is Your Headquarters to Dream, Discover

Hotel Los Arcos de Sonora is your May, 2011 headquarters to Dream, Discover and Explore. Hola de Banámichi! The desert waits... Viva Mexico! for the summer rains to come. The cottonwoods along the river are green, the mesquite trees leafed Beat the snow up north with a visit to out. The cactus are blooming. Time to Dream, Discover and Explore the wonders of Northern Mexico. Sonora. Call now to book your Banámichi break-away. Hotel Los Arcos is just five hours Banámichi means cowboys. This is where the cowboy culture and traditions still thrive. And it from Tucson and 3 hours from thrives with a uniquely Mexican flair. The Mexican cowboy is called a vaquero, from vaca for cow Bisbee. or, literally cowman. Since the Spanish colonization, Sonora was engaged in cattle ranching and cattle and cowboys still flourish here. Click here for maps and directions Photographer Kendall Nelson, author of Gathering Remnants: A Tribute to the Working Cowboy , (http://www.gatheringremnants.com) says this about cowboy culture: "All of the skills, traditions, and ways of working with cattle are very much rooted in the Mexican vaquero. If you are a cowboy in the U.S. today, you have developed what you know from the vaquero." In fact, one out of every three cowboys working in the US in the late 1800s was a Mexican vaquero. It’s difficult to speak about cowboys or the work of cowboying without using Upcoming Events Spanish words. Lariat comes from "la rieta," the vaqueros hand May 7 and 8 - International Mountain braided rawhide rope. -

The Conquistadors and the Iberian Horse “For, After God, We Owed the Victory to the Horses.” Bernal Díaz 1569

The Conquistadors and the Iberian Horse “For, after God, we owed the victory to the horses.” Bernal Díaz 1569 By Sarah Gately-Wilson When Spain claimed the New World, the Iberian horse was there to help. These original Iberian horses are not the Andalusians and Lusitanos as we know them today, but their ancestors, a little smaller, stockier, but with the same inherent traits that today make the Iberian horse so desirable! On his second voyage in 1493, Christopher Columbus brought the Iberian horse to the Americas. Every subsequent expedition also contained Iberians in its Cargo. Breeding farms were established in the Caribbean to provide mounts for the Conquistadors as they explored and settled the New World. These original Iberians became the foundation stock for all American breeds of horse to follow. The Mustangs, Pasos, and Criollos still strongly resemble their ancestors, but few realize that the Morgan, American Saddlebred, and the American Quarter Horse, to name a few, are also descendants of the Iberian horse. A grulla American Quarter Horse. The Conquistador’s Iberians came in many coat colors. Many of the Conquistadors that traveled to the New World came from Extremadura, a section of Spain just northwest of Andalucia. The men and their horses were used to the dry hard land of southern Spain. The horses survived the four month voyage across the Atlantic, cramped into tight areas and with restricted diets. Upon arrival, the horses had to swim to land before starting out on their next voyage over rugged terrain to carry the men through jungles and swamps into uncharted territories.