If You Have Issues Viewing Or Accessing This File, Please Contact Us at NCJRS.Gov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

Hohonu Volume 5 (PDF)

HOHONU 2007 VOLUME 5 A JOURNAL OF ACADEMIC WRITING This publication is available in alternate format upon request. TheUniversity of Hawai‘i is an Equal Opportunity Affirmative Action Institution. VOLUME 5 Hohonu 2 0 0 7 Academic Journal University of Hawai‘i at Hilo • Hawai‘i Community College Hohonu is publication funded by University of Hawai‘i at Hilo and Hawai‘i Community College student fees. All production and printing costs are administered by: University of Hawai‘i at Hilo/Hawai‘i Community College Board of Student Publications 200 W. Kawili Street Hilo, Hawai‘i 96720-4091 Phone: (808) 933-8823 Web: www.uhh.hawaii.edu/campuscenter/bosp All rights revert to the witers upon publication. All requests for reproduction and other propositions should be directed to writers. ii d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d Table of Contents 1............................ A Fish in the Hand is Worth Two on the Net: Don’t Make me Think…different, by Piper Seldon 4..............................................................................................Abortion: Murder-Or Removal of Tissue?, by Dane Inouye 9...............................An Etymology of Four English Words, with Reference to both Grimm’s Law and Verner’s Law by Piper Seldon 11................................Artifacts and Native Burial Rights: Where do We Draw the Line?, by Jacqueline Van Blarcon 14..........................................................................................Ayahuasca: Earth’s Wisdom Revealed, by Jennifer Francisco 16......................................Beak of the Fish: What Cichlid Flocks Reveal About Speciation Processes, by Holly Jessop 26................................................................................. Climatic Effects of the 1815 Eruption of Tambora, by Jacob Smith 33...........................Columnar Joints: An Examination of Features, Formation and Cooling Models, by Mary Mathis 36.................... -

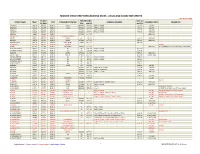

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

Family Ties and Political Participation*

Family Ties and Political Participation∗ Alberto Alesina and Paola Giuliano Harvard University, Igier Bocconi and UCLA April 2009 Abstract We establish an inverse relationship between family ties, generalized trust and political participation. The more individuals rely on the family as a provider of services, insurance, transfer of resources, the lower is civic engagement and political participation. The latter, together with trust, are part of what is known as social capital, therefore in this paper we contribute to the investigation of the origin and evolution of social capital over time. We establish these results using within country evidence and looking at the behavior of immigrants from various countries in 32 different destination places. ∗Prepared for the JEEA lecture, American Economic Assocition meeting, January 2008. We thank Dorian Carloni and Giampaolo Lecce for excellent research assistanship. 1 1Introduction Well functioning democracies need citizens’ participation in politics. Political participation is a broader concept than simply voting in elections and it includes a host of activities like volunteering as an unpaid campaign worker, debating politics with others and attending political meetings like campaign appearances of candidates, joining political groups, participating in boycott activities, strikes or demonstrations, writing letters to representatives and so on.1 What deter- mines it? The purpose of this paper is to investigate an hypothesis put forward by Banfield (1958) in his study of a Southern Italian village. He defines "amoral familism" as a social equilibrium in which people trust (and care about) ex- clusively their immediate family, expect everybody else to behave in that way and therefore (rationally) do not trust non family members and do not expect to be trusted outside the family2 . -

The Morgan's Role out West

THE MORGAN’S ROLE OUT WEST CELEBRATED AT VAQUERO HERITAGE DAYS 2012 By Brenda L. Tippin Stories of cowboys and the old west have always captivated Americans with their romance. The California vaquero was, in fact, America’s first cowboy and the Morgan horse was the first American breed regularly used by many of these early vaqueros. Renewed interest in the vaquero style of horsemanship in recent years has opened up huge new markets for breeders, trainers, and artisans, and the Morgan horse is stepping up to take his rightful place as an important part of California Vaquero Heritage. THE MORGAN CONNECTION and is becoming more widely recognized as what is known as the The Justin Morgan horse shared similar origins with the horses of “baroque” style horse, along with such breeds as the Andalusian, the Spanish conquistadors, who were the forefathers of the vaquero Lippizan, and Kiger Mustangs, which are all favored as being most traditions. The Conquistador horses, brought in by the Moors, like the horse of the Conquistadors. These breeds have the powerful, carried the blood of the ancient Barb, Arab, and Oriental horses— deep rounded body type; graceful arched necks set upright, coming the same predominant lines which may be found in the pedigree out of the top of the shoulder; and heavy manes and tails similar of Justin Morgan in Volume I of the Morgan Register. In recent to the European paintings of the Baroque period, which resemble years, the old style foundation Morgan has gained in popularity today’s original type Morgans to a remarkable degree. -

Stories of Words: Spanish

Stories of Words: Spanish By: Elfrieda H. Hiebert & Wendy Svec Stories of Words: Spanish, Second Edition © 2018 TextProject, Inc. Some rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-937889-23-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. “TextProject” and the TextProject logo are trademarks of TextProject, Inc. Cover photo ©2016 istockphoto.com/valentinrussanov. All rights reserved. Used under license. 2 Contents Learning About Words ...............................4 Chapter 1: Everyday Sayings .....................5 Chapter 2: ¡Buen Apetito! ...........................8 Chapter 3: Cockroaches to Cowboys ......12 Chapter 4: ¡Vámonos! ...............................15 Chapter 5: It’s Raining Gatos & Perros!....18 Our Changing Language ..........................21 Glossary ...................................................22 Think About It ...........................................23 3 Learning About Words Hola! Welcome to America, where you can see and hear the Spanish language all around you. Look at street signs or on menus. You will probably see Spanish words or names. Listen to the radio or television. It is likely you will hear Spanish being spoken. Since Spanish-speaking people first arrived in North America in the 16th century, the Spanish language has been part of American culture. Some people are being raised in Spanish-speaking homes and communities. Other people are taking classes to learn to speak and read Spanish. As a result, Spanish has become the second most spoken language in the United States. Every day, millions of Americans are speaking Spanish. -

N Roll Forever (A Tribute to the 80’S) ______

PRESS KIT: Rock ‘n Roll Forever (a tribute to the 80’s) _____________________________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – 12/21/12 Rock ‘n Roll Forever (a tribute to the 80’s) Rock ‘n Roll Forever (a tribute to the 80’s) Directed by John Fagan Music Director – Joe Wehunt January 24 – February 23, 2013 Thurs. – Sat. 8pm Sun. 3pm Your favorite 80’s music comes to Centre Stage in this original Rock ‘n Roll show. This musical tribute will feature songs from myriad 80’s stars. CSSC Rock ‘n Roll shows have been audience pleasers for the last three years. The originally produced shows sell out so quickly that we have decided to run the show for five weekends instead of the regular four. We hope that this will allow many more audience members to be able to come and experience Rock ‘n Roll-Centre Stage style. Joe Wehunt, our music director, has worked with Bob Hope, George Burns, The Fifth Dimension and as a musical director for many productions. Joe puts together an amazing group of vocalists and musicians to treat our patrons to a night they will never forget. Many of our guests come back two and three times to see the show. Tickets for Rock ‘n Roll Forever are $30 for adults and seniors, and $25 for juniors (ages 4-18). Student rush tickets available 15 minutes prior to show time for $20 with school ID (day of, based on availability), one ticket per ID. Shows run Thursday through Sunday and all seats are reserved. You can reach the box office at 864-233-6733 or visit us online at www.centrestage.org. -

Foreign Consular Offices in the United States

United States Department of State Foreign Consular Offices in the United States Spring/Summer2011 STATE DEPARTMENT ADDRESSEE *IF YOU DO NOT WISH TO CONTINUE RECEIVING THIS PUBLICATION PLEASE WRITE CANCEL ON THE ADDRESS LABEL *IF WE ARE ADDRESSING YOU INCORRECTLY PLEASE INDICATE CORRECTIONS ON LABEL RETURN LABEL AND NAME OF PUBLICATION TO THE OFFICE OF PROTOCOL, DEPARTMENT OF STATE, WASHINGTON, D.C. 20520-1853 DEPARTMENT OF STATE PUBLICATION 11106 Revised May 24, 2011 ______________________________________________________________________________ For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 FOREIGN CONSULAR OFFICES IN THE UNITED STATES i PREFACE This publication contains a complete and official listing of the foreign consular offices in the United States, and recognized consular officers. Compiled by the U.S. Department of State, with the full cooperation of the foreign missions in Washington, it is offered as a convenience to organizations and persons who must deal with consular representatives of foreign governments. It has been designed with particular attention to the requirements of government agencies, state tax officials, international trade organizations, chambers of commerce, and judicial authorities who have a continuing need for handy access to this type of information. Trade with other regions of the world has become an increasingly vital element in the economy of the United States. The machinery of this essential commerce is complicated by numerous restrictions, license requirements, quotas, and other measures adopted by the individual countries. Since the regulations affecting both trade and travel are the particular province of the consular service of the nations involved, reliable information as to entrance requirements, consignment of goods, details of transshipment, and, in many instances, suggestions as to consumer needs and preferences may be obtained at the foreign consular offices throughout the United States. -

Doma Vaquero My Journey in Understanding Spanish Traditions

Written by Alice Trindle Copyright: T&T Horsemanship May 2006 No portion of this article can be reproduced without the consent of the author Doma Vaquero My Journey in Understanding By Alice Trindle Spanish Traditions appreciate in the Quarter Horse were originally t all started with a horse! Juandero was a I placed in the gene pool by the Spanish beautiful bay Azteca gelding. He didn’t just Andalusian. The conquistadors brought the appear at my place…He arrived! His presence Spanish blood horses into Mexico during the was unmistakably alive, somewhat full of himself, Aztec era, and later on they brought them into but aware of everything around him and quite what became the continental United States with prepared to play. As I had the honor to begin to Spanish missionaries, and the Spanish army. work with Juandero I soon discovered there was These horses were very agile and athletic, as their more to this picture then a beautiful horse, with a heritage was to fight the bulls of Spain. Even willing and playful attitude, that carried himself in today, these bulls are not your average polled a natural balance that was light and suspended. Hereford with a docile temperament! The Spanish There was a tradition – a heritage – that was bull is bred for attitude with horns, and therefore exhibiting itself in every movement of this horse your horse must be able to leg-yield or half-pass, and I wanted to know more about it. canter and counter-canter, in balance and at various speeds. In Spain, the Doma Vaquero uses a 13-foot long wood pole called the garrocha for working the bulls, as well as a partner in an elegant dance and artistic display between horse, rider, and pole, set to beautiful Spanish guitar music. -

San Diego Sheriff's Department Family TIES Program

SAN DIEGO SHERIFF’S DEPARTMENT FAMILY TIES PROGRAM: LIFE SKILLS FOR SAN DIEGO INMATES FINAL REPORT DECEMBER 2006 Liz Doroski Sandy Keaton, M.A. Sylvia J. Sievers, Ph.D. Cynthia Burke, Ph.D. This research was supported by the United States Department of Education. Opinions in this report are the authors’ and may not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Education. 401 B Street, Suite 800 • San Diego, CA 92101-4231 • (619) 699-1900 BOARD OF DIRECTORS The 18 cities and county government are SANDAG serving as the forum for regional decision-making. SANDAG builds consensus; plans, engineers, and builds public transit; makes strategic plans; obtains and allocates resources; and provides information on a broad range of topics pertinent to the region’s quality of life. CHAIR: Hon. Mickey Cafagna FIRST VICE CHAIR: Hon. Mary Teresa Sessom SECOND VICE CHAIR: Hon. Lori Holt Pfeiler EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Gary L. Gallegos CITY OF CARLSBAD CITY OF SAN MARCOS Hon. Matt Hall, Mayor Pro Tem Hon. Pia Harris-Ebert, Vice Mayor (A) Hon. Bud Lewis, Mayor (A) Hon. Hal Martin, Councilmember (A) Hon. Ann Kulchin, Councilmember (A) Hon. Corky Smith, Mayor CITY OF CHULA VISTA CITY OF SANTEE Hon. Steve Padilla, Mayor Hon. Jack Dale, Councilmember (A) Hon. Jerry Rindone, Councilmember (A) Hon. Hal Ryan, Councilmember (A) Hon. John McCann, Deputy Mayor (A) Hon. Randy Voepel, Mayor CITY OF CORONADO CITY OF SOLANA BEACH Hon. Phil Monroe, Councilmember Hon Joe Kellejian, Councilmember (A) Hon. Frank Tierney, Councilmember (A) Hon. Lesa Heebner, Deputy Mayor (A) Hon. Carrie Downey, Councilmember (A) Hon. David Powell, Mayor CITY OF DEL MAR CITY OF VISTA Hon. -

Chapter 6: End of Spanish Rule

End of Spanish Rule Why It Matters Europeans had ruled the New World for centuries. In the late 1700s people in the Americas began to throw off European rule. The thirteen English colonies were first. The French colony of Haiti was next. Texas was one part of the grand story of the independence of the Spanish colonies. For the people living in Texas, though, the transition from Spanish province to a territory in the independent nation of Mexico was tremendously important. The Impact Today • Texas was the region of North America in which Spanish, French, English, and Native Americans met. • Contact among people encourages new ways of thinking. Later the number of groups in Texas increased as African and Asian people, as well as others from all over the world, brought their cultures. 1773 1760 ★ Spanish 1779 ★ Atascosito Road used for abandon East • Nacogdoches military purposes Texas missions founded 1760 1770 1780 1790 1763 1773 1789 • Treaty of Paris ended • Captain James Cook crossed • George Washington Seven Years’ War the Antarctic Circle became first president 1783 1793 • Great Britain and United • Eli Whitney States signed peace treaty invented the cotton gin 136 CHAPTER 6 End of Spanish Rule Summarizing Study Foldable Make this foldable and use it as a journal to help you record key facts about the time when Spain ruled Texas. Step 1 Stack four sheets of paper, one on top of the other. On the top sheet of paper, trace a large circle. Step 2 With the papers still stacked, cut out all four circles at the same time. -

031906 It's a Parade of Stars As Tv Land Honors Dallas

Contacts: Jennifer Zaldivar Vanessa Reyes TV Land TV Land 646/228-2479 310/752-8081 IT’S A PARADE OF STARS AS TV LAND HONORS DALLAS, CHEERS, GOOD TIMES, BATMAN AND GREY’S ANATOMY Diana Ross, Billy Crystal, Hilary Swank, Patrick Dempsey, Robert Downey Jr., Mary Tyler Moore, Sid Caesar, Patrick Duffy, Larry Hagman, Ted Danson, Kelsey Grammer, John Amos, Jimmy “JJ” Walker, Jeremy Piven and Quentin Tarantino Among Dozens of Performers Celebrating Classic TV Santa Monica, CA, March 19, 2006 – It was an unforgettable evening as celebrities from television, music and film bestowed special tribute awards tonight to some of television’s most beloved series and stars at the fourth annual TV Land Awards: A Celebration of Classic TV . The honored shows included Cheers (Legend Award), Dallas (Pop Culture Award), Good Times (Impact Award), Batman (40 th Anniversary) and Grey’s Anatomy (Future Classic Award). The TV Land Awards was taped at The Barker Hangar on Sunday, March 19 and will air on TV Land (and simulcast on Nick at Nite) Wednesday, March 22 from 9 p.m. to 11 p.m. ET/PT. This star-studded extravaganza featured some unforgettable moments such as when actor and comedian Billy Crystal presented TV icon Sid Caesar with The Pioneer Award. Grammy award-winning superstar Diana Ross performing a medley of her famous hits including “Touch Me in the Morning,” “The Boss,” “Do You Know,” and “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.” Acclaimed actor Robert Downey Jr. presented two-time Oscar winner Hilary Swank with the Big Screen/Little Star award.