Vacuum Tube Amplifiers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El156 Audio Power

EL156 AUDIO POWER Gerhard Haas Thanks to its robustness, the legendary EL156 audio power pentode has found its way into many professional amplifier units. Its attraction derives not just from its appealing shape, but also from its impressive audio characteristics. We therefore bring you this classical circuit, updated using high- quality modern components. 28 elektor electronics - 3/2005 AMPLIFIER Return of a legend The EL156 was manufactured in the enough to give adequate sensitivity, electrolytic capacitor: this voltage is legendary Telefunken valve factory in even before allowing any margin for further filtered on the amplifier board. Ulm, near the river Danube in Ger- negative feedback. The ECC81 many. The EL156 made amplifiers with (12AT7), however, which has an open- It is not possible to build an ultra-lin- an output power of up to 130 W possi- loop gain of 60 and which can be oper- ear amplifier using the EL156 with a ble, using just two valves in the output ated with anode currents of up to high anode voltage. The same goes for stage and one driver valve. Genuine 10 mA, can be used to build a suitably the EL34. The output transformer is EL156s are no longer available new at low-impedance circuit. therefore connected in such a way that realistic prices, and hardly any are Two EL156s can be used to produce an the impedance of the grid connection available second-hand. The original output power of 130 W with only 6 % to the output valve is much lower than devices used a metal valve base which distortion. -

Vacuum Tube Theory, a Basics Tutorial – Page 1

Vacuum Tube Theory, a Basics Tutorial – Page 1 Vacuum Tubes or Thermionic Valves come in many forms including the Diode, Triode, Tetrode, Pentode, Heptode and many more. These tubes have been manufactured by the millions in years gone by and even today the basic technology finds applications in today's electronics scene. It was the vacuum tube that first opened the way to what we know as electronics today, enabling first rectifiers and then active devices to be made and used. Although Vacuum Tube technology may appear to be dated in the highly semiconductor orientated electronics industry, many Vacuum Tubes are still used today in applications ranging from vintage wireless sets to high power radio transmitters. Until recently the most widely used thermionic device was the Cathode Ray Tube that was still manufactured by the million for use in television sets, computer monitors, oscilloscopes and a variety of other electronic equipment. Concept of thermionic emission Thermionic basics The simplest form of vacuum tube is the Diode. It is ideal to use this as the first building block for explanations of the technology. It consists of two electrodes - a Cathode and an Anode held within an evacuated glass bulb, connections being made to them through the glass envelope. If a Cathode is heated, it is found that electrons from the Cathode become increasingly active and as the temperature increases they can actually leave the Cathode and enter the surrounding space. When an electron leaves the Cathode it leaves behind a positive charge, equal but opposite to that of the electron. In fact there are many millions of electrons leaving the Cathode. -

Operation, Tetrode, Pentode in the Single-Ended, Class-A

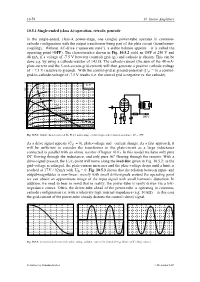

10-76 10. Guitar Amplifiers 10.5.1 Single-ended (class A)-operation, tetrode, pentode In the single-ended, class-A power-stage, one (single) power-tube operates in common- cathode configuration with the output transformer being part of the plate circuit (transformer- coupling). Without AC-drive (“quiescent state”), a stable balance appears – it is called the operating point (OPP). The characteristics shown in Fig. 10.5.2 yield an OPP at 250 V and 48 mA, if a voltage of -7.5 V between (control) grid (g1) and cathode is chosen. This can be done e.g. by using a cathode-resistor of 142 Ω. The cathode-current (the sum of the 48-mA- plate-current and the 5-mA-screen-grid-current) will then generate a positive cathode-voltage of + 7.5 V (relative to ground). With the control-grid at ground-potential (Ug1 = 0) a control- grid-to-cathode-voltage of -7.5 V results (i.e. the control grid is negative vs. the cathode). Fig. 10.5.2: Output characteristics of the EL84, power-stage circuit (single-ended class-A operation). AP = OPP As a drive signal appears (Ug1 ≠ 0), plate-voltage and –current change. As a first approach, it will be sufficient to consider the transformer in the plate-circuit as a large inductance connected in parallel with an ohmic resistor (Chapter 10.6). In this model we have only pure DC flowing through the inductance, and only pure AC flowing through the resistor. With a drive-signal present, the Ua/Ia-point will move along the load-line given in Fig. -

Philips DEALING with TECHNICAL PROBLEMS

VOL. 5 N~. 3 . Philips DEALING WITH TECHNICAL PROBLEMS. RELATING TO THE PRODUCTS, PROCESSES AND. INVESTIGATIONS OF N.V. PHILIPS' GLOEILAMPENFABRIEKEN EDITED BY THE RESEARCH LABORATORY OF N.V. PHILIPS' GLOEILAMPENFABRIEKEN, EINDHOVEN, HOLLAND TESTING A~PLIFIER OUTPUT VALVES BY MEANS OF THE 'CAT~ODE RAY TUBE hy A. J. HEINS van der VEN. 621.317.755: 621.396.645 I n testing amplifier output valves, the most important data are contained in the In' v.. diagram if one knows over which part of the diagram the values of voltage and current prevailing during operatien range, i;e. if the position of the load line is known. The la- Vn 'diagrams as well as the load lines can very easily b~ obtained with the help of a 'cathode ray tube. The necessary apparatus is described in this article. A number of auxiliary ar- rangernents are also studied, by which the axes and the necessary calibration lines in the diagram can be traced on the fluorescent screen, and which make it possible to. cause the diagrams of two .output valves which are to be compared to appear simultancously on the screen. In order to obtain the load line in the correct place in the diagram, use must he made of dir'ect current push-pull amplifiers for the deflection voltages of the cathode ray tube. The position of the load line upon inductive loading is discussed and explained by a number of examples. In conclusion one,npplication of the instaflation in the develop- ment of output pentodes is dealt with. If one wishes to characterize briefly the perfor- quantrties are to some degree dependent _on the mance of an output valve of !tn amplifier or radio loading impedance which is included in the anode set, it is enough to give the sensitivity, the distor- circuit, it is first necessary to find out how the loa'd- tion as a function of the power output, and in some ing of the ~alve is e~pl'esse~ in the Ia- V~ curve.' , cases the maximum power which can he delivered mA without grid current flowing. -

INDUSTRIAL STRENGTH by MICHAEL RIORDAN

THE INDUSTRIAL STRENGTH by MICHAEL RIORDAN ORE THAN A DECADE before J. J. Thomson discovered the elec- tron, Thomas Edison stumbled across a curious effect, patented Mit, and quickly forgot about it. Testing various carbon filaments for electric light bulbs in 1883, he noticed a tiny current trickling in a single di- rection across a partially evacuated tube into which he had inserted a metal plate. Two decades later, British entrepreneur John Ambrose Fleming applied this effect to invent the “oscillation valve,” or vacuum diode—a two-termi- nal device that converts alternating current into direct. In the early 1900s such rectifiers served as critical elements in radio receivers, converting radio waves into the direct current signals needed to drive earphones. In 1906 the American inventor Lee de Forest happened to insert another elec- trode into one of these valves. To his delight, he discovered he could influ- ence the current flowing through this contraption by changing the voltage on this third electrode. The first vacuum-tube amplifier, it served initially as an improved rectifier. De Forest promptly dubbed his triode the audion and ap- plied for a patent. Much of the rest of his life would be spent in forming a se- ries of shaky companies to exploit this invention—and in an endless series of legal disputes over the rights to its use. These pioneers of electronics understood only vaguely—if at all—that individual subatomic particles were streaming through their devices. For them, electricity was still the fluid (or fluids) that the classical electrodynamicists of the nineteenth century thought to be related to stresses and disturbances in the luminiferous æther. -

Pentodes Connected As Triodes

Pentodes connected as Triodes by Tom Schlangen Pentodes connected as Triodes About the author Tom Schlangen Born 1962 in Cologne / Germany Studied mechanical engineering at RWTH Aachen / Germany Employments as „safety engineering“ specialist and CIO / IT-head in middle-sized companies, now owning and running an IT- consultant business aimed at middle-sized companies Hobby: Electron valve technology in audio Private homepage: www.tubes.mynetcologne.de Private email address: [email protected] Tom Schlangen – ETF 06 2 Pentodes connected as Triodes Reasons for connecting and using pentodes as triodes Why using pentodes as triodes at all? many pentodes, especially small signal radio/TV ones, are still available from huge stock cheap as dirt, because nobody cares about them (especially “TV”-valves), some of them, connected as triodes, can rival even the best real triodes for linearity, some of them, connected as triodes, show interesting characteristics regarding µ, gm and anode resistance, that have no expression among readily available “real” triodes, because it is fun to try and find out. Tom Schlangen – ETF 06 3 Pentodes connected as Triodes How to make a triode out of a tetrode or pentode again? Or, what to do with the “superfluous” grids? All additional grids serve a certain purpose and function – they were added to a basic triode system to improve the system behaviour in certain ways, for example efficiency. We must “disable” the functions of those additional grids in a defined and controlled manner to regain triode characteristics. Just letting them “dangle in vacuum unconnected” will not work – they would charge up uncontrolled in the electron stream, leading to unpredictable behaviour. -

Lee De Forest Claimet\He Got the Idea for His Triode ''Audion" From

Lee de Forest claimet\he got the idea for his triode h ''audion" from wntching a gas flame bum. John Ambrose Flen#ng thought that story ·~just so much hot air. lreJess telegraphy held excit m WIng promise at the beginning of the twentieth century. Peo ~With Imagination could seethe po.. tentlal thot 'the rematkoble new technology offered forworlct1Nk:le com munfcotion. However, no one could hove predicted the impact that the soon-to-be-developed "osdllotlon volve" ond "oudlon" Wireless-telegra phy detector& wauid have on elec tronics technology. Backpouncl. Shortly before 1900, · Guglielmo Morconl had formed his own company to develop wireless telegraphy technology. He demon strated that wireless set-ups on ships eot~ld~messageswlth nearby stations on other ships or on land. t The Marconi Company hOd also j transmitted messages across the EhQ Jish Channel. By the end of 1901. Mar coni extended the range of his equipmenttospantheAtlan1tcOcean. It was obvlgus. 1hot ~raph ~MeS with subrhatlrie cables and ihelr lnber ent flmltations woUld soon disappear, Ships· at sea would no longer be iso la1ed. No locatlon on Eorth would. be too remote to send and receive mes sages. Clear1y; the opportunity existed tor enormous tiOOnciql gain once Jelio ble equlprrient was avoltable. To that end, 1Uned electrical circuits were developed to reduce the band width of the signals produced by ,the spark transrnlf'tirs. The resonont clfcults were also used in a receiver to select one signal from omong several trans missions. Slm~deslgn principles for resonont ontennas were also being explored and applied, However, the senstflvlty and reUabltlty of the devices used to ctetectthe Wireless signals were still hln cterlng the development of commer () cial wireless-telegraph nefWorks. -

Eimac Care and Feeding of Tubes Part 3

SECTION 3 ELECTRICAL DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS 3.1 CLASS OF OPERATION Most power grid tubes used in AF or RF amplifiers can be operated over a wide range of grid bias voltage (or in the case of grounded grid configuration, cathode bias voltage) as determined by specific performance requirements such as gain, linearity and efficiency. Changes in the bias voltage will vary the conduction angle (that being the portion of the 360° cycle of varying anode voltage during which anode current flows.) A useful system has been developed that identifies several common conditions of bias voltage (and resulting anode current conduction angle). The classifications thus assigned allow one to easily differentiate between the various operating conditions. Class A is generally considered to define a conduction angle of 360°, class B is a conduction angle of 180°, with class C less than 180° conduction angle. Class AB defines operation in the range between 180° and 360° of conduction. This class is further defined by using subscripts 1 and 2. Class AB1 has no grid current flow and class AB2 has some grid current flow during the anode conduction angle. Example Class AB2 operation - denotes an anode current conduction angle of 180° to 360° degrees and that grid current is flowing. The class of operation has nothing to do with whether a tube is grid- driven or cathode-driven. The magnitude of the grid bias voltage establishes the class of operation; the amount of drive voltage applied to the tube determines the actual conduction angle. The anode current conduction angle will determine to a great extent the overall anode efficiency. -

Photomultiplier Tubes 1)-5)

CHAPTER 2 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF PHOTOMULTIPLIER TUBES 1)-5) A photomultiplier tube is a vacuum tube consisting of an input window, a photocathode, focusing electrodes, an electron multiplier and an anode usu- ally sealed into an evacuated glass tube. Figure 2-1 shows the schematic construction of a photomultiplier tube. FOCUSING ELECTRODE SECONDARY ELECTRON LAST DYNODE STEM PIN VACUUM (~10P-4) DIRECTION e- OF LIGHT FACEPLATE STEM ELECTRON MULTIPLIER ANODE (DYNODES) PHOTOCATHODE THBV3_0201EA Figure 2-1: Construction of a photomultiplier tube Light which enters a photomultiplier tube is detected and produces an output signal through the following processes. (1) Light passes through the input window. (2) Light excites the electrons in the photocathode so that photoelec- trons are emitted into the vacuum (external photoelectric effect). (3) Photoelectrons are accelerated and focused by the focusing elec- trode onto the first dynode where they are multiplied by means of secondary electron emission. This secondary emission is repeated at each of the successive dynodes. (4) The multiplied secondary electrons emitted from the last dynode are finally collected by the anode. This chapter describes the principles of photoelectron emission, electron tra- jectory, and the design and function of electron multipliers. The electron multi- pliers used for photomultiplier tubes are classified into two types: normal dis- crete dynodes consisting of multiple stages and continuous dynodes such as mi- crochannel plates. Since both types of dynodes differ considerably in operating principle, photomultiplier tubes using microchannel plates (MCP-PMTs) are separately described in Chapter 10. Furthermore, electron multipliers for vari- ous particle beams and ion detectors are discussed in Chapter 12. -

A Practical Approach to Transist Vacuum Tube Amplifiers

A PRACTICAL APPROACH TO TRANSIST VACUUM TUBE AMPLIFIERS BY F. J. BECKETT TEKTRONIX, INC. ELECTRONIC INSTRUMENTATION GROUP DISPLAY DEVICES DEVELOPMENT Two articles published in past issues of Service Scope contained information that, in our experience, is of particular benefit in analyzing circuits. The first article was "Sim- plifying Transistor Linear-Amplifier Analysis" (issue #29, December, 1964). It describes a method for doing an adequate circuit analysis for trouble-shooting or evaluation pur- poses on transistor circuits. It employs "Transresistance" concept rather than the compli- cated characteristic-family parameters. The second article was "Understanding and Using Th6venin's Theorem" (issue #40, October, 1966). It offers a step-by-step explanation on how to apply the principles of ThBvenin's Theorem to analyze and understand how a circuit operates. Now we present three articles that will offer a practical approach to transistor and vacuum-tube amplifiers based on a simple DC analysis. These articles will, by virtue of additional information and tying together of some loose ends, combine and bring into better focus the concepts of "Transresistance." Part I THE TRANSISTOR AMPLIFIER INTRODUCTION Tubes and transistors are often used to- there is an analogy between the two. It 50, it seems pointless not to pursue this ap- gether to achieve a particular result. Vacu- is true of course, that the two are entire- proach to its logical conclusion. um tubes still serve an important role in ly different in concept; but, so often we In this first article we will look at a electronics and will do so for many years come across a situation where one can be transistor amplifier as a simple DC model ; to come despite a determined move towards explained in terms of the other that it is and then, in the second article, look at a solid state circuits. -

Lorentz Force Demonstrator

LORENTZ FORCE DEMONSTRATOR LFD001 1 10 2 9 3 4 8 5 6 7 Figure 1 GENERAL DESCRIPTION The LFD001 Lorentz Force Demonstrator is a “fine beam tube” device in which a sharply focused electron beam is projected into a vacuum containing a trace of inert gas. Ionization of the gas around the electron beam creates a glowing discharge marking the path of the electrons and helping to maintain the sharp focus of the beam. The demonstrator shows deflection of the beam by transverse electric fields and by magnetic fields of various orientations. The value of e/m can be found by bending the electron beam into a circular path with a homogeneous magnetic field and measuring the accelerating voltage of the electron gun, the strength of the magnetic field, and the radius of the circular beam path. The components of the device are shown in Figure 1: 1. “Fine beam” vacuum tube 6. Accelerating and deflection voltage controls 2. Helmholtz coils 7. Power and coil current controls 3. Transparent metric ruler 8. Accelerating voltage and coil current meters 4. Angle scale and pointer for tube 9. Mirror for parallax elimination 5. Current direction indicators 10. Case with black interior for better visibility 847-336-7556 1 www.unitedsci.com SPECIFICATIONS Fine beam vacuum tube Diameter: 160mm Rotation: tube and socket rotate ±180° Angle scale: 0° — ±180° x 5° Accelerating voltage: 250V max. Helmholtz coils: Coil mean diameter: 280mm Coil separation: 140mm 140 turns per coil Max. current: 2.5A Power supply unit: Accelerating voltage: 0—250V dc Coil current:0.5—2.5A, reversible, with current direction indicators Electrostatic deflecting voltage: 50—250V, reversible Accuracy of meters: ±2.5% Power input: 110VAC 60Hz, 45W Maximum continuous operation: 1 hour Operating conditions: Temperature: 0 – 40°C, Humidity: 20 –80% Dimensions: 35cm x 30cm x 45cm (l x w x h) Weight: 11kg CONTROLS 12 11 9 10 4 6 5 1 2 3 8 7 Figure 2 Figure 2 shows the front panel of the power supply unit: 1. -

Cathode Ray Tube

Cathode ray tube Quick reference guide Introduction The Cathode Ray Tube or Braun’s Tube was invented by the German physicist Karl Ferdinand Braun in 1897 and is today used in computer monitors, TV sets and oscilloscope tubes. The path of the electrons in the tube filled with a low pressure rare gas can be observed in a darkened room as a trace of light. Electron beam deflection can be effected by means of either an electrical or a magnetic field. Functional principle • The source of the electron beam is the electron gun, which produces a stream of electrons through thermionic emission at the heated cathode and focuses it into a thin beam by the control grid (or “Wehnelt cylinder”). • A strong electric field between cathode and anode accelerates the electrons, before they leave the electron gun through a small hole in the anode. • The electron beam can be deflected by a capacitor or coils in a way which causes it to display an image on the screen. The image may represent electrical waveforms (oscilloscope), pictures (television, computer monitor), echoes of aircraft detected by radar etc. • When electrons strike the fluorescent screen, light is emitted. • The whole configuration is placed in a vacuum tube to avoid collisions between electrons and gas molecules of the air, which would attenuate the beam. Flourescent screen Cathode Control grid Anode UA - 1 - CERN Teachers Lab Cathode ray tube Safety precautions • Don’t touch cathode ray tube and cables during operation, voltages of 300 V are used in this experiment! • Do not exert mechanical force on the tube, danger of implosions! ! Experimental procedure 1.