CHEMISTRY 135 Energy of Phase Changes[1]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physical Model for Vaporization

Physical model for vaporization Jozsef Garai Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Florida International University, University Park, VH 183, Miami, FL 33199 Abstract Based on two assumptions, the surface layer is flexible, and the internal energy of the latent heat of vaporization is completely utilized by the atoms for overcoming on the surface resistance of the liquid, the enthalpy of vaporization was calculated for 45 elements. The theoretical values were tested against experiments with positive result. 1. Introduction The enthalpy of vaporization is an extremely important physical process with many applications to physics, chemistry, and biology. Thermodynamic defines the enthalpy of vaporization ()∆ v H as the energy that has to be supplied to the system in order to complete the liquid-vapor phase transformation. The energy is absorbed at constant pressure and temperature. The absorbed energy not only increases the internal energy of the system (U) but also used for the external work of the expansion (w). The enthalpy of vaporization is then ∆ v H = ∆ v U + ∆ v w (1) The work of the expansion at vaporization is ∆ vw = P ()VV − VL (2) where p is the pressure, VV is the volume of the vapor, and VL is the volume of the liquid. Several empirical and semi-empirical relationships are known for calculating the enthalpy of vaporization [1-16]. Even though there is no consensus on the exact physics, there is a general agreement that the surface energy must be an important part of the enthalpy of vaporization. The vaporization diminishes the surface energy of the liquid; thus this energy must be supplied to the system. -

LATENT HEAT of FUSION INTRODUCTION When a Solid Has Reached Its Melting Point, Additional Heating Melts the Solid Without a Temperature Change

LATENT HEAT OF FUSION INTRODUCTION When a solid has reached its melting point, additional heating melts the solid without a temperature change. The temperature will remain constant at the melting point until ALL of the solid has melted. The amount of heat needed to melt the solid depends upon both the amount and type of matter that is being melted. Therefore: Q = ML Eq. 1 f where Q is the amount of heat absorbed by the solid, M is the mass of the solid that was melted and Lf is the latent heat of fusion for the type of material that was melted, which is measured in J/kg, NOTE: to fuse means to melt. In this experiment the latent heat of fusion of water will be determined by using the method of mixtures ΣQ=0, or QGained +QLost =0. Ice will be added to a calorimeter containing warm water. The heat energy lost by the water and calorimeter does two things: 1. It melts the ice; 2. It warms the water formed by the melting ice from zero to the final equilibrium temperature of the mixture. Heat gained + Heat lost = 0 Heat needed to melt ice + Heat needed to warm the melt water + Heat lost by warn water = 0 MiceLf + MiceCw (Tf - 0) + MwCw (Tf – Tw) = 0 Eq. 2. * Note: The mass of the melted water is the same as the mass of the ice. where M = mass of warm water initially in calorimeter w Mice = mass of ice and water from the melted ice Cw = specific heat of water Lf = latent heat of fusion of water Tw = initial temperature water Tf = equilibrium temperature of mixture APPARATUS: Calorimeter, thermometer, balance, ice, water OBJECTIVE: To determine the latent heat of fusion of water PROCEDURE: 1. -

Equation of State for Benzene for Temperatures from the Melting Line up to 725 K with Pressures up to 500 Mpa†

High Temperatures-High Pressures, Vol. 41, pp. 81–97 ©2012 Old City Publishing, Inc. Reprints available directly from the publisher Published by license under the OCP Science imprint, Photocopying permitted by license only a member of the Old City Publishing Group Equation of state for benzene for temperatures from the melting line up to 725 K with pressures up to 500 MPa† MONIKA THOL ,1,2,* ERIC W. Lemm ON 2 AND ROLAND SPAN 1 1Thermodynamics, Ruhr-University Bochum, Universitaetsstrasse 150, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2National Institute of Standards and Technology, 325 Broadway, Boulder, Colorado 80305, USA Received: December 23, 2010. Accepted: April 17, 2011. An equation of state (EOS) is presented for the thermodynamic properties of benzene that is valid from the triple point temperature (278.674 K) to 725 K with pressures up to 500 MPa. The equation is expressed in terms of the Helmholtz energy as a function of temperature and density. This for- mulation can be used for the calculation of all thermodynamic properties. Comparisons to experimental data are given to establish the accuracy of the EOS. The approximate uncertainties (k = 2) of properties calculated with the new equation are 0.1% below T = 350 K and 0.2% above T = 350 K for vapor pressure and liquid density, 1% for saturated vapor density, 0.1% for density up to T = 350 K and p = 100 MPa, 0.1 – 0.5% in density above T = 350 K, 1% for the isobaric and saturated heat capaci- ties, and 0.5% in speed of sound. Deviations in the critical region are higher for all properties except vapor pressure. -

Determination of the Identity of an Unknown Liquid Group # My Name the Date My Period Partner #1 Name Partner #2 Name

Determination of the Identity of an unknown liquid Group # My Name The date My period Partner #1 name Partner #2 name Purpose: The purpose of this lab is to determine the identity of an unknown liquid by measuring its density, melting point, boiling point, and solubility in both water and alcohol, and then comparing the results to the values for known substances. Procedure: 1) Density determination Obtain a 10mL sample of the unknown liquid using a graduated cylinder Determine the mass of the 10mL sample Save the sample for further use 2) Melting point determination Set up an ice bath using a 600mL beaker Obtain a ~5mL sample of the unknown liquid in a clean dry test tube Place a thermometer in the test tube with the sample Place the test tube in the ice water bath Watch for signs of crystallization, noting the temperature of the sample when it occurs Save the sample for further use 3) Boiling point determination Set up a hot water bath using a 250mL beaker Begin heating the water in the beaker Obtain a ~10mL sample of the unknown in a clean, dry test tube Add a boiling stone to the test tube with the unknown Open the computer interface software, using a graph and digit display Place the temperature sensor in the test tube so it is in the unknown liquid Record the temperature of the sample in the test tube using the computer interface Watch for signs of boiling, noting the temperature of the unknown Dispose of the sample in the assigned waste container 4) Solubility determination Obtain two small (~1mL) samples of the unknown in two small test tubes Add an equal amount of deionized into one of the samples Add an equal amount of ethanol into the other Mix both samples thoroughly Compare the samples for solubility Dispose of the samples in the assigned waste container Observations: The unknown is a clear, colorless liquid. -

Dry Ice Blasting

Dry Ice Blasting The Dry Ice Blasting method can reduce the overall time spent on sanding, scraping or scrub- bing with solvents, acids and other cleaning agents. With no secondary waste generation there is no need for disposal of hazardous waste. This saves time and money while increasing worker safety. Online Cleaning of Fin Dry Ice Blasting can safely and effectively clean contaminants that plug and foul fin fan heat Fan Heat Exchangers exchangers. Dry Ice Blasting can be performed while the system is online so no costly downtime is required. Cleaning will increase airflow which will lower approach temperatures and increase efficiency. The dry nature of the process will mitigate the potential for harming motors, bearings or instrumentation. Other Applications May The demand to keep the equipment running often leads to deferred cleaning and maintenance, Also Benefit reduced efficiency and in some cases, outages caused by flashover. Dry ice blast cleaning can provide a non-conductive cleaning process that may allow equipment to be cleaned in-place without cool down or disassembly. This includes generators, turbines, stators, rotors, compressors and boilers. Industrial cleaning applications exist in markets as diverse as food & beverage equipment clean-up, pharmaceutical production, aerospace surfaces & components, and foundry core- making machinery. A Leading Supplier of Working with Linde Services offers you product reliability from an industry leader in carbon Carbon Dioxide dioxide applications. This includes: → A focus on safety -

The Basics of Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium (Or Why the Tripoli L2 Tech Question #30 Is Wrong)

The Basics of Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium (Or why the Tripoli L2 tech question #30 is wrong) A question on the Tripoli L2 exam has the wrong answer? Yes, it does. What is this errant question? 30.Above what temperature does pressurized nitrous oxide change to a gas? a. 97°F b. 75°F c. 37°F The correct answer is: d. all of the above. The answer that is considered correct, however, is: a. 97ºF. This is the critical temperature above which N2O is neither a gas nor a liquid; it is a supercritical fluid. To understand what this means and why the correct answer is “all of the above” you have to know a little about the behavior of liquids and gases. Most people know that water boils at 212ºF. Most people also know that when you’re, for instance, boiling an egg in the mountains, you have to boil it longer to fully cook it. The reason for this has to do with the vapor pressure of water. Every liquid wants to vaporize to some extent. The measure of this tendency is known as the vapor pressure and varies as a function of temperature. When the vapor pressure of a liquid reaches the pressure above it, it boils. Until then, it evaporates until the fraction of vapor in the mixture above it is equal to the ratio of the vapor pressure to the total pressure. At that point it is said to be in equilibrium and no further liquid will evaporate. The vapor pressure of water at 212ºF is 14.696 psi – the atmospheric pressure at sea level. -

Single Crystal Growth of Mgb2 by Using Low Melting Point Alloy Flux

Single Crystal Growth of Magnesium Diboride by Using Low Melting Point Alloy Flux Wei Du*, Xugang Xian, Xiangjin Zhao, Li Liu, Zhuo Wang, Rengen Xu School of Environment and Material Engineering, Yantai University, Yantai 264005, P. R. China Abstract Magnesium diboride crystals were grown with low melting alloy flux. The sample with superconductivity at 38.3 K was prepared in the zinc-magnesium flux and another sample with superconductivity at 34.11 K was prepared in the cadmium-magnesium flux. MgB4 was found in both samples, and MgB4’s magnetization curve being above zero line had not superconductivity. Magnesium diboride prepared by these two methods is all flaky and irregular shape and low quality of single crystal. However, these two metals should be the optional flux for magnesium diboride crystal growth. The study of single crystal growth is very helpful for the future applications. Keywords: Crystal morphology; Low melting point alloy flux; Magnesium diboride; Superconducting materials Corresponding author. Tel: +86-13235351100 Fax: +86-535-6706038 Email-address: [email protected] (W. Du) 1. Introduction Since the discovery of superconductivity in Magnesium diboride (MgB2) with a transition temperature (Tc) of 39K [1], a great concern has been given to this material structure, just as high-temperature copper oxide can be doped by elements to improve its superconducting temperature. Up to now, it is failure to improve Tc of doped MgB2 through C [2-3], Al [4], Li [5], Ir [6], Ag [7], Ti [8], Ti, Zr and Hf [9], and Be [10] on the contrary, the Tc is reduced or even disappeared. -

Liquid-Vapor Equilibrium in a Binary System

Liquid-Vapor Equilibria in Binary Systems1 Purpose The purpose of this experiment is to study a binary liquid-vapor equilibrium of chloroform and acetone. Measurements of liquid and vapor compositions will be made by refractometry. The data will be treated according to equilibrium thermodynamic considerations, which are developed in the theory section. Theory Consider a liquid-gas equilibrium involving more than one species. By definition, an ideal solution is one in which the vapor pressure of a particular component is proportional to the mole fraction of that component in the liquid phase over the entire range of mole fractions. Note that no distinction is made between solute and solvent. The proportionality constant is the vapor pressure of the pure material. Empirically it has been found that in very dilute solutions the vapor pressure of solvent (major component) is proportional to the mole fraction X of the solvent. The proportionality constant is the vapor pressure, po, of the pure solvent. This rule is called Raoult's law: o (1) psolvent = p solvent Xsolvent for Xsolvent = 1 For a truly ideal solution, this law should apply over the entire range of compositions. However, as Xsolvent decreases, a point will generally be reached where the vapor pressure no longer follows the ideal relationship. Similarly, if we consider the solute in an ideal solution, then Eq.(1) should be valid. Experimentally, it is generally found that for dilute real solutions the following relationship is obeyed: psolute=K Xsolute for Xsolute<< 1 (2) where K is a constant but not equal to the vapor pressure of pure solute. -

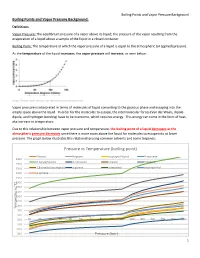

Pressure Vs Temperature (Boiling Point)

Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background: Definitions Vapor Pressure: The equilibrium pressure of a vapor above its liquid; the pressure of the vapor resulting from the evaporation of a liquid above a sample of the liquid in a closed container. Boiling Point: The temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid is equal to the atmospheric (or applied) pressure. As the temperature of the liquid increases, the vapor pressure will increase, as seen below: https://www.chem.purdue.edu/gchelp/liquids/vpress.html Vapor pressure is interpreted in terms of molecules of liquid converting to the gaseous phase and escaping into the empty space above the liquid. In order for the molecules to escape, the intermolecular forces (Van der Waals, dipole- dipole, and hydrogen bonding) have to be overcome, which requires energy. This energy can come in the form of heat, aka increase in temperature. Due to this relationship between vapor pressure and temperature, the boiling point of a liquid decreases as the atmospheric pressure decreases since there is more room above the liquid for molecules to escape into at lower pressure. The graph below illustrates this relationship using common solvents and some terpenes: Pressure vs Temperature (boiling point) Ethanol Heptane Isopropyl Alcohol B-myrcene 290.0 B-caryophyllene d-Limonene Linalool Pulegone 270.0 250.0 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) a-pinene a-terpineol terpineol-4-ol 230.0 p-cymene 210.0 190.0 170.0 150.0 130.0 110.0 90.0 Temperature (˚C) Temperature 70.0 50.0 30.0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 200 300 400 500 600 760 10.0 -10.0 -30.0 Pressure (torr) 1 Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background As a very general rule of thumb, the boiling point of many liquids will drop about 0.5˚C for a 10mmHg decrease in pressure when operating in the region of 760 mmHg (atmospheric pressure). -

It's Just a Phase!

BASIS Lesson Plan Lesson Name: It’s Just a Phase! Grade Level Connection(s) NGSS Standards: Grade 2, Physical Science FOSS CA Edition: Grade 3 Physical Science: Matter and Energy Module *Note to teachers: Detailed standards connections can be found at the end of this lesson plan. Teaser/Overview Properties of matter are illustrated through a series of demonstrations and hands-on explorations. Students will learn to identify solids, liquids, and gases. Water will be used to demonstrate the three phases. Students will learn about sublimation through a fun experiment with dry ice (solid CO2). Next, they will compare the propensity of several liquids to evaporate. Finally, they will learn about freezing and melting while making ice cream. Lesson Objectives ● Students will be able to identify the three states of matter (solid, liquid, gas) based on the relative properties of those states. ● Students will understand how to describe the transition from one phase to another (melting, freezing, evaporation, condensation, sublimation) ● Students will learn that matter can change phase when heat/energy is added or removed Vocabulary Words ● Solid: A phase of matter that is characterized by a resistance to change in shape and volume. ● Liquid: A phase of matter that is characterized by a resistance to change in volume; a liquid takes the shape of its container ● Gas: A phase of matter that can change shape and volume ● Phase change: Transformation from one phase of matter to another ● Melting: Transformation from a solid to a liquid ● Freezing: Transformation -

NASA Spacecraft Observes Further Evidence of Dry Ice Gullies on Mars 11 July 2014, by Guy Webster

NASA spacecraft observes further evidence of dry ice gullies on Mars 11 July 2014, by Guy Webster "As recently as five years ago, I thought the gullies on Mars indicated activity of liquid water," said lead author Colin Dundas of the U.S. Geological Survey's Astrogeology Science Center in Flagstaff, Arizona. "We were able to get many more observations, and as we started to see more activity and pin down the timing of gully formation and change, we saw that the activity occurs in winter." Dundas and collaborators used the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on MRO to examine gullies at 356 sites on Mars, beginning in 2006. Thirty-eight of the sites showed active gully formation, such as new channel segments and increased deposits at the downhill end of some gullies. Using dated before-and-after images, researchers determined the timing of this activity coincided with This pair of images covers one of the hundreds of sites seasonal carbon-dioxide frost and temperatures on Mars where researchers have repeatedly used the that would not have allowed for liquid water. High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter to study changes in gullies on slopes. Credit: NASA/JPL- Frozen carbon dioxide, commonly called dry ice, Caltech/Univ. of Arizona does not exist naturally on Earth, but is plentiful on Mars. It has been linked to active processes on Mars such as carbon dioxide gas geysers and lines on sand dunes plowed by blocks of dry ice. One Repeated high-resolution observations made by mechanism by which carbon-dioxide frost might NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) drive gully flows is by gas that is sublimating from indicate the gullies on Mars' surface are primarily the frost providing lubrication for dry material to formed by the seasonal freezing of carbon dioxide, flow. -

Fast Synthesis of Fe1.1Se1-Xtex Superconductors in a Self-Heating

Fast synthesis of Fe1.1Se1-xTe x superconductors in a self-heating and furnace-free way Guang-Hua Liu1,*, Tian-Long Xia2,*, Xuan-Yi Yuan2, Jiang-Tao Li1,*, Ke-Xin Chen3, Lai-Feng Li1 1. Key Laboratory of Cryogenics, Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, P. R. China 2.Department of Physics, Beijing Key Laboratory of Opto-electronic Functional Materials & Micro-nano Devices, Renmin University of China, Beijing 100872, P. R. China 3. State Key Laboratory of New Ceramics & Fine Processing, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, P. R. China *Corresponding authors: Guang-Hua Liu, E-mail: [email protected] Tian-Long Xia, E-mail: [email protected] Jiang-Tao Li, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A fast and furnace-free method of combustion synthesis is employed for the first time to synthesize iron-based superconductors. Using this method, Fe1.1Se1-xTe x (0≤x≤1) samples can be prepared from self-sustained reactions of element powders in only tens of seconds. The obtained Fe1.1Se1-xTe x samples show clear zero resistivity and corresponding magnetic susceptibility drop at around 10-14 K. The Fe1.1Se0.33Te 0.67 sample shows the highest onset Tc of about 14 K, and its upper critical field is estimated to be approximately 54 T. Compared with conventional solid state reaction for preparing polycrystalline FeSe samples, combustion synthesis exhibits much-reduced time and energy consumption, but offers comparable superconducting properties. It is expected that the combustion synthesis method is available for preparing plenty of iron-based superconductors, and in this direction further related work is in progress.