Phase Diagrams a Phase Diagram Is Used to Show the Relationship Between Temperature, Pressure and State of Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes: BCS Theory of Superconductivity

Lecture Notes: BCS theory of superconductivity Prof. Rafael M. Fernandes Here we will discuss a new ground state of the interacting electron gas: the superconducting state. In this macroscopic quantum state, the electrons form coherent bound states called Cooper pairs, which dramatically change the macroscopic properties of the system, giving rise to perfect conductivity and perfect diamagnetism. We will mostly focus on conventional superconductors, where the Cooper pairs originate from a small attractive electron-electron interaction mediated by phonons. However, in the so- called unconventional superconductors - a topic of intense research in current solid state physics - the pairing can originate even from purely repulsive interactions. 1 Phenomenology Superconductivity was discovered by Kamerlingh-Onnes in 1911, when he was studying the transport properties of Hg (mercury) at low temperatures. He found that below the liquifying temperature of helium, at around 4:2 K, the resistivity of Hg would suddenly drop to zero. Although at the time there was not a well established model for the low-temperature behavior of transport in metals, the result was quite surprising, as the expectations were that the resistivity would either go to zero or diverge at T = 0, but not vanish at a finite temperature. In a metal the resistivity at low temperatures has a constant contribution from impurity scattering, a T 2 contribution from electron-electron scattering, and a T 5 contribution from phonon scattering. Thus, the vanishing of the resistivity at low temperatures is a clear indication of a new ground state. Another key property of the superconductor was discovered in 1933 by Meissner. -

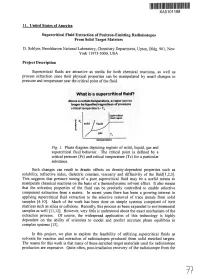

Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Positron-Emitting Radioisotopes from Solid Target Matrices

XA0101188 11. United States of America Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Positron-Emitting Radioisotopes From Solid Target Matrices D. Schlyer, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Chemistry Department, Upton, Bldg. 901, New York 11973-5000, USA Project Description Supercritical fluids are attractive as media for both chemical reactions, as well as process extraction since their physical properties can be manipulated by small changes in pressure and temperature near the critical point of the fluid. What is a supercritical fluid? Above a certain temperature, a vapor can no longer be liquefied regardless of pressure critical temperature - Tc supercritical fluid r«gi on solid a u & temperature Fig. 1. Phase diagram depicting regions of solid, liquid, gas and supercritical fluid behavior. The critical point is defined by a critical pressure (Pc) and critical temperature (Tc) for a particular substance. Such changes can result in drastic effects on density-dependent properties such as solubility, refractive index, dielectric constant, viscosity and diffusivity of the fluid[l,2,3]. This suggests that pressure tuning of a pure supercritical fluid may be a useful means to manipulate chemical reactions on the basis of a thermodynamic solvent effect. It also means that the solvation properties of the fluid can be precisely controlled to enable selective component extraction from a matrix. In recent years there has been a growing interest in applying supercritical fluid extraction to the selective removal of trace metals from solid samples [4-10]. Much of the work has been done on simple systems comprised of inert matrices such as silica or cellulose. Recently, this process as been expanded to environmental samples as well [11,12]. -

Physical Model for Vaporization

Physical model for vaporization Jozsef Garai Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Florida International University, University Park, VH 183, Miami, FL 33199 Abstract Based on two assumptions, the surface layer is flexible, and the internal energy of the latent heat of vaporization is completely utilized by the atoms for overcoming on the surface resistance of the liquid, the enthalpy of vaporization was calculated for 45 elements. The theoretical values were tested against experiments with positive result. 1. Introduction The enthalpy of vaporization is an extremely important physical process with many applications to physics, chemistry, and biology. Thermodynamic defines the enthalpy of vaporization ()∆ v H as the energy that has to be supplied to the system in order to complete the liquid-vapor phase transformation. The energy is absorbed at constant pressure and temperature. The absorbed energy not only increases the internal energy of the system (U) but also used for the external work of the expansion (w). The enthalpy of vaporization is then ∆ v H = ∆ v U + ∆ v w (1) The work of the expansion at vaporization is ∆ vw = P ()VV − VL (2) where p is the pressure, VV is the volume of the vapor, and VL is the volume of the liquid. Several empirical and semi-empirical relationships are known for calculating the enthalpy of vaporization [1-16]. Even though there is no consensus on the exact physics, there is a general agreement that the surface energy must be an important part of the enthalpy of vaporization. The vaporization diminishes the surface energy of the liquid; thus this energy must be supplied to the system. -

LATENT HEAT of FUSION INTRODUCTION When a Solid Has Reached Its Melting Point, Additional Heating Melts the Solid Without a Temperature Change

LATENT HEAT OF FUSION INTRODUCTION When a solid has reached its melting point, additional heating melts the solid without a temperature change. The temperature will remain constant at the melting point until ALL of the solid has melted. The amount of heat needed to melt the solid depends upon both the amount and type of matter that is being melted. Therefore: Q = ML Eq. 1 f where Q is the amount of heat absorbed by the solid, M is the mass of the solid that was melted and Lf is the latent heat of fusion for the type of material that was melted, which is measured in J/kg, NOTE: to fuse means to melt. In this experiment the latent heat of fusion of water will be determined by using the method of mixtures ΣQ=0, or QGained +QLost =0. Ice will be added to a calorimeter containing warm water. The heat energy lost by the water and calorimeter does two things: 1. It melts the ice; 2. It warms the water formed by the melting ice from zero to the final equilibrium temperature of the mixture. Heat gained + Heat lost = 0 Heat needed to melt ice + Heat needed to warm the melt water + Heat lost by warn water = 0 MiceLf + MiceCw (Tf - 0) + MwCw (Tf – Tw) = 0 Eq. 2. * Note: The mass of the melted water is the same as the mass of the ice. where M = mass of warm water initially in calorimeter w Mice = mass of ice and water from the melted ice Cw = specific heat of water Lf = latent heat of fusion of water Tw = initial temperature water Tf = equilibrium temperature of mixture APPARATUS: Calorimeter, thermometer, balance, ice, water OBJECTIVE: To determine the latent heat of fusion of water PROCEDURE: 1. -

Determination of the Identity of an Unknown Liquid Group # My Name the Date My Period Partner #1 Name Partner #2 Name

Determination of the Identity of an unknown liquid Group # My Name The date My period Partner #1 name Partner #2 name Purpose: The purpose of this lab is to determine the identity of an unknown liquid by measuring its density, melting point, boiling point, and solubility in both water and alcohol, and then comparing the results to the values for known substances. Procedure: 1) Density determination Obtain a 10mL sample of the unknown liquid using a graduated cylinder Determine the mass of the 10mL sample Save the sample for further use 2) Melting point determination Set up an ice bath using a 600mL beaker Obtain a ~5mL sample of the unknown liquid in a clean dry test tube Place a thermometer in the test tube with the sample Place the test tube in the ice water bath Watch for signs of crystallization, noting the temperature of the sample when it occurs Save the sample for further use 3) Boiling point determination Set up a hot water bath using a 250mL beaker Begin heating the water in the beaker Obtain a ~10mL sample of the unknown in a clean, dry test tube Add a boiling stone to the test tube with the unknown Open the computer interface software, using a graph and digit display Place the temperature sensor in the test tube so it is in the unknown liquid Record the temperature of the sample in the test tube using the computer interface Watch for signs of boiling, noting the temperature of the unknown Dispose of the sample in the assigned waste container 4) Solubility determination Obtain two small (~1mL) samples of the unknown in two small test tubes Add an equal amount of deionized into one of the samples Add an equal amount of ethanol into the other Mix both samples thoroughly Compare the samples for solubility Dispose of the samples in the assigned waste container Observations: The unknown is a clear, colorless liquid. -

Equation of State and Phase Transitions in the Nuclear

National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine Bogolyubov Institute for Theoretical Physics Has the rights of a manuscript Bugaev Kyrill Alekseevich UDC: 532.51; 533.77; 539.125/126; 544.586.6 Equation of State and Phase Transitions in the Nuclear and Hadronic Systems Speciality 01.04.02 - theoretical physics DISSERTATION to receive a scientific degree of the Doctor of Science in physics and mathematics arXiv:1012.3400v1 [nucl-th] 15 Dec 2010 Kiev - 2009 2 Abstract An investigation of strongly interacting matter equation of state remains one of the major tasks of modern high energy nuclear physics for almost a quarter of century. The present work is my doctor of science thesis which contains my contribution (42 works) to this field made between 1993 and 2008. Inhere I mainly discuss the common physical and mathematical features of several exactly solvable statistical models which describe the nuclear liquid-gas phase transition and the deconfinement phase transition. Luckily, in some cases it was possible to rigorously extend the solutions found in thermodynamic limit to finite volumes and to formulate the finite volume analogs of phases directly from the grand canonical partition. It turns out that finite volume (surface) of a system generates also the temporal constraints, i.e. the finite formation/decay time of possible states in this finite system. Among other results I would like to mention the calculation of upper and lower bounds for the surface entropy of physical clusters within the Hills and Dales model; evaluation of the second virial coefficient which accounts for the Lorentz contraction of the hard core repulsing potential between hadrons; inclusion of large width of heavy quark-gluon bags into statistical description. -

Physics, Chapter 17: the Phases of Matter

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 17: The Phases of Matter Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 17: The Phases of Matter" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 165. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/165 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 17 The Phases of Matter 17-1 Phases of a Substance A substance which has a definite chemical composition can exist in one or more phases, such as the vapor phase, the liquid phase, or the solid phase. When two or more such phases are in equilibrium at any given temperature and pressure, there are always surfaces of separation between the two phases. In the solid phase a pure substance generally exhibits a well-defined crystal structure in which the atoms or molecules of the substance are arranged in a repetitive lattice. Many substances are known to exist in several different solid phases at different conditions of temperature and pressure. These solid phases differ in their crystal structure. Thus ice is known to have six different solid phases, while sulphur has four different solid phases. -

Lecture 15: 11.02.05 Phase Changes and Phase Diagrams of Single- Component Materials

3.012 Fundamentals of Materials Science Fall 2005 Lecture 15: 11.02.05 Phase changes and phase diagrams of single- component materials Figure removed for copyright reasons. Source: Abstract of Wang, Xiaofei, Sandro Scandolo, and Roberto Car. "Carbon Phase Diagram from Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics." Physical Review Letters 95 (2005): 185701. Today: LAST TIME .........................................................................................................................................................................................2� BEHAVIOR OF THE CHEMICAL POTENTIAL/MOLAR FREE ENERGY IN SINGLE-COMPONENT MATERIALS........................................4� The free energy at phase transitions...........................................................................................................................................4� PHASES AND PHASE DIAGRAMS SINGLE-COMPONENT MATERIALS .................................................................................................6� Phases of single-component materials .......................................................................................................................................6� Phase diagrams of single-component materials ........................................................................................................................6� The Gibbs Phase Rule..................................................................................................................................................................7� Constraints on the shape of -

Single Crystal Growth of Mgb2 by Using Low Melting Point Alloy Flux

Single Crystal Growth of Magnesium Diboride by Using Low Melting Point Alloy Flux Wei Du*, Xugang Xian, Xiangjin Zhao, Li Liu, Zhuo Wang, Rengen Xu School of Environment and Material Engineering, Yantai University, Yantai 264005, P. R. China Abstract Magnesium diboride crystals were grown with low melting alloy flux. The sample with superconductivity at 38.3 K was prepared in the zinc-magnesium flux and another sample with superconductivity at 34.11 K was prepared in the cadmium-magnesium flux. MgB4 was found in both samples, and MgB4’s magnetization curve being above zero line had not superconductivity. Magnesium diboride prepared by these two methods is all flaky and irregular shape and low quality of single crystal. However, these two metals should be the optional flux for magnesium diboride crystal growth. The study of single crystal growth is very helpful for the future applications. Keywords: Crystal morphology; Low melting point alloy flux; Magnesium diboride; Superconducting materials Corresponding author. Tel: +86-13235351100 Fax: +86-535-6706038 Email-address: [email protected] (W. Du) 1. Introduction Since the discovery of superconductivity in Magnesium diboride (MgB2) with a transition temperature (Tc) of 39K [1], a great concern has been given to this material structure, just as high-temperature copper oxide can be doped by elements to improve its superconducting temperature. Up to now, it is failure to improve Tc of doped MgB2 through C [2-3], Al [4], Li [5], Ir [6], Ag [7], Ti [8], Ti, Zr and Hf [9], and Be [10] on the contrary, the Tc is reduced or even disappeared. -

Phase Diagrams

Module-07 Phase Diagrams Contents 1) Equilibrium phase diagrams, Particle strengthening by precipitation and precipitation reactions 2) Kinetics of nucleation and growth 3) The iron-carbon system, phase transformations 4) Transformation rate effects and TTT diagrams, Microstructure and property changes in iron- carbon system Mixtures – Solutions – Phases Almost all materials have more than one phase in them. Thus engineering materials attain their special properties. Macroscopic basic unit of a material is called component. It refers to a independent chemical species. The components of a system may be elements, ions or compounds. A phase can be defined as a homogeneous portion of a system that has uniform physical and chemical characteristics i.e. it is a physically distinct from other phases, chemically homogeneous and mechanically separable portion of a system. A component can exist in many phases. E.g.: Water exists as ice, liquid water, and water vapor. Carbon exists as graphite and diamond. Mixtures – Solutions – Phases (contd…) When two phases are present in a system, it is not necessary that there be a difference in both physical and chemical properties; a disparity in one or the other set of properties is sufficient. A solution (liquid or solid) is phase with more than one component; a mixture is a material with more than one phase. Solute (minor component of two in a solution) does not change the structural pattern of the solvent, and the composition of any solution can be varied. In mixtures, there are different phases, each with its own atomic arrangement. It is possible to have a mixture of two different solutions! Gibbs phase rule In a system under a set of conditions, number of phases (P) exist can be related to the number of components (C) and degrees of freedom (F) by Gibbs phase rule. -

Phase Transitions in Multicomponent Systems

Physics 127b: Statistical Mechanics Phase Transitions in Multicomponent Systems The Gibbs Phase Rule Consider a system with n components (different types of molecules) with r phases in equilibrium. The state of each phase is defined by P,T and then (n − 1) concentration variables in each phase. The phase equilibrium at given P,T is defined by the equality of n chemical potentials between the r phases. Thus there are n(r − 1) constraints on (n − 1)r + 2 variables. This gives the Gibbs phase rule for the number of degrees of freedom f f = 2 + n − r A Simple Model of a Binary Mixture Consider a condensed phase (liquid or solid). As an estimate of the coordination number (number of nearest neighbors) think of a cubic arrangement in d dimensions giving a coordination number 2d. Suppose there are a total of N molecules, with fraction xB of type B and xA = 1 − xB of type A. In the mixture we assume a completely random arrangement of A and B. We just consider “bond” contributions to the internal energy U, given by εAA for A − A nearest neighbors, εBB for B − B nearest neighbors, and εAB for A − B nearest neighbors. We neglect other contributions to the internal energy (or suppose them unchanged between phases, etc.). Simple counting gives the internal energy of the mixture 2 2 U = Nd(xAεAA + 2xAxBεAB + xBεBB) = Nd{εAA(1 − xB) + εBBxB + [εAB − (εAA + εBB)/2]2xB(1 − xB)} The first two terms in the second expression are just the internal energy of the unmixed A and B, and so the second term, depending on εmix = εAB − (εAA + εBB)/2 can be though of as the energy of mixing. -

Introduction to Phase Diagrams*

ASM Handbook, Volume 3, Alloy Phase Diagrams Copyright # 2016 ASM InternationalW H. Okamoto, M.E. Schlesinger and E.M. Mueller, editors All rights reserved asminternational.org Introduction to Phase Diagrams* IN MATERIALS SCIENCE, a phase is a a system with varying composition of two com- Nevertheless, phase diagrams are instrumental physically homogeneous state of matter with a ponents. While other extensive and intensive in predicting phase transformations and their given chemical composition and arrangement properties influence the phase structure, materi- resulting microstructures. True equilibrium is, of atoms. The simplest examples are the three als scientists typically hold these properties con- of course, rarely attained by metals and alloys states of matter (solid, liquid, or gas) of a pure stant for practical ease of use and interpretation. in the course of ordinary manufacture and appli- element. The solid, liquid, and gas states of a Phase diagrams are usually constructed with a cation. Rates of heating and cooling are usually pure element obviously have the same chemical constant pressure of one atmosphere. too fast, times of heat treatment too short, and composition, but each phase is obviously distinct Phase diagrams are useful graphical representa- phase changes too sluggish for the ultimate equi- physically due to differences in the bonding and tions that show the phases in equilibrium present librium state to be reached. However, any change arrangement of atoms. in the system at various specified compositions, that does occur must constitute an adjustment Some pure elements (such as iron and tita- temperatures, and pressures. It should be recog- toward equilibrium. Hence, the direction of nium) are also allotropic, which means that the nized that phase diagrams represent equilibrium change can be ascertained from the phase dia- crystal structure of the solid phase changes with conditions for an alloy, which means that very gram, and a wealth of experience is available to temperature and pressure.