Physics, Chapter 17: the Phases of Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Measures of Humidity Phases of Water

Chapter 5 Atmospheric Moisture Measures of Humidity 1. Absolute humidity 2. Specific humidity 3. Actual vapor pressure 4. Saturation vapor pressure 5. Relative humidity 6. Dew point Phases of Water Water Vapor n o su ti b ra li o n m p io d a a at ep t v s o io e en s n d it n io o n c freezing Liquid Water Ice melting 1 Coexistence of Water & Vapor • Even below the boiling point, some water molecules leave the liquid (evaporation). • Similarly, some water molecules from the air enter the liquid (condense). • The behavior happens over ice too (sublimation and condensation). Saturation • If we cap the air over the water, then more and more water molecules will enter the air until saturation is reached. • At saturation there is a balance between the number of water molecules leaving the liquid and entering it. • Saturation can occur over ice too. Hydrologic Cycle 2 Air Parcel • Enclose a volume of air in an imaginary thin elastic container, which we will call an air parcel. • It contains oxygen, nitrogen, water vapor, and other molecules in the air. 1. Absolute Humidity Mass of water vapor Absolute humidity = Volume of air The absolute humidity changes with the volume of the parcel, which can change with temperature or pressure. 2. Specific Humidity Mass of water vapor Specific humidity = Total mass of air The specific humidity does not change with parcel volume. 3 Specific Humidity vs. Latitude • The highest specific humidities are observed in the tropics and the lowest values in the polar regions. -

Parallel-Powered Hybrid Cycle with Superheating “Partially” by Gas

Parallel-Powered Hybrid Cycle with Superheating “Partially” by Gas Turbine Exhaust Milad Ghasemi, Hassan Hammodi, Homan Moosavi Sigaroodi ETA800 Final Thesis Project Division of Heat and Power Technology Department of Energy Technology Royal Institute of Technology Stockholm, Sweden [This page is left intentionally blank for the purposes of printing] Abstract It is of great importance to acquire methods that has a sustainable solution for treatment and disposal of municipal solid waste (MSW). The volumes are constantly increasing and improper waste management, like open dumping and landfilling, causes environmental impacts such as groundwater contamination and greenhouse gas emissions. The rationalization of developing a sustainable solution implies in an improved way of utilizing waste resources as an energy source with highest possible efficiency. MSW incineration is by far the best available way to dispose the waste. One drawback of conventional MSW incineration plants is that when the energy recovery occurs in the steam power cycle configuration, the reachable efficiency is limited due to steam parameters. The corrosive problem limits the temperature of the superheated steam from the boiler which lowers the efficiency of the system. A suitable and relatively cheap option for improving the efficiency of the steam power cycle is the implementation of a hybrid dual-fuel cycle. This paper aims to assess the integration of an MSW incineration with a high quality fuel conversion device, in this case natural gas (NG) combustion cycle, in a hybrid cycle. The aforementioned hybrid dual-fuel configuration combines a gas turbine topping cycle (TC) and a steam turbine bottoming cycle (BC). The TC utilizes the high quality fuel NG, while the BC uses the lower quality fuel, MSW, and reaches a total power output of 50 MW. -

Impurity Effects in Thermal Regelation

Soft Matter View Article Online PAPER View Journal | View Issue Impurity effects in thermal regelation a ab Cite this: Soft Matter, 2020, Navaneeth K. Marath and J. S. Wettlaufer * 16, 5886 When a particle is placed in a material with a lower bulk melting temperature, intermolecular forces can lead to the existence of a ‘‘premelted’’ liquid film of the lower melting temperature material. Despite the system being below the melting temperatures of both solids, the liquid film is a consequence of thermodynamic equilibrium, controlled by intermolecular, ionic and other interactions. An imposed Received 30th March 2020, temperature gradient drives the translation of the particle by a process of melting and refreezing known as Accepted 17th May 2020 ‘‘thermal regelation’’. We calculate the rate of regelation of spherical particles surrounded by premelted DOI: 10.1039/d0sm00558d films that contain ionic impurities. The impurities enhance the rate of motion thereby influencing the dynamics of single particles and distributions of particles, which we describe in addition to the rsc.li/soft-matter-journal consequences in natural and technological settings. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. 1 Introduction translational velocity and displacement of the particle, when it is subjected to a temperature gradient. Lastly, we develop Premelted liquid films can separate the surface of a solid from the theory to understand the combined effects of thermal a foreign substrate at temperatures below the solid’s bulk regelation and diffusion on the particle motion. In Section 3, melting temperature. The solid melts against the substrate in we describe the displacement of particles of different sizes order to minimize the free energy of the solid–liquid–substrate and impurity concentrations for various temperature gradients. -

Chapter 3: Supporting PPT Slides

ESO201A Department of Mechanical Engineering Thermodynamics Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Instructor: Dr. Sameer Khandekar Kanpur 208016 Tel: 7038; e-mail: [email protected] India Phase Diagrams 1 © Sameer Khandekar ESO201A Department of Mechanical Engineering Thermodynamics Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Instructor: Dr. Sameer Khandekar Kanpur 208016 Tel: 7038; e-mail: [email protected] India Increasing the temperature isobarically T-v diagram of constant-pressure phase-change processes of a pure substance at various pressures numerical values are for water. 2 © Sameer Khandekar ESO201A Department of Mechanical Engineering Thermodynamics Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Instructor: Dr. Sameer Khandekar Kanpur 208016 Tel: 7038; e-mail: [email protected] India Temperature - Volume diagram 3 © Sameer Khandekar ESO201A Department of Mechanical Engineering Thermodynamics Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Instructor: Dr. Sameer Khandekar Kanpur 208016 Tel: 7038; e-mail: [email protected] India Pressure – Volume diagram The pressure is gradually reduced by removing the weights 4 © Sameer Khandekar ESO201A Department of Mechanical Engineering Thermodynamics Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Instructor: Dr. Sameer Khandekar Kanpur 208016 Tel: 7038; e-mail: [email protected] India P-v-T surfaces Remembering: (i) The State Postulate: The state of a simple compressible substance is fixed by any two independent, intensive properties and (ii) Any equation with two independent variables in the form z = z (x, y) represents a surface 5 © Sameer Khandekar ESO201A Department of Mechanical Engineering Thermodynamics Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Instructor: Dr. Sameer Khandekar Kanpur 208016 Tel: 7038; e-mail: [email protected] India P-v-T Surface of a substance that expands on freezing. -

Thermodynamics of Air-Vapour Mixtures Module A

roJuclear Reactor Containment Design Chapter 4: Thermodynamics ofAir-Vapour Mixtures Dr. Johanna Daams page 4A - 1 Module A: Introduction to Modelling CHAPTER 4: THERMODYNAMICS OF AIR-VAPOUR MIXTURES MODULE A: INTRODUCTION TO MODELLING MODULE OBJECTIVES: At the end of this module, you will be able to describe: 1. The three types of modelling, required for nuclear stations 2. The differences between safety code, training simulator code and engineering code ,... --, Vuclear Reector Conte/nment Design Chapter 4: Thermodynamics ofAir-Vapour Mixtures ". Johanna Daams page 4A-2 Module A: Introduction to Modelling 1.0 TYPES OF MODELLING CODE n the discussion of mathematical modelling of containment that follows, I will often say that certain !pproxlmatlons are allowable for simple simulations, and that safety analysis require more elaborate :alculations. Must therefore understand requirements for different types of simulation. 1.1 Simulation for engineering (design and post-construction design changes): • Purpose: Initially confirm system is within design parameters • limited scope - only parts of plant, few scenarios - and detail; • Simplified representation of overall plant or of a system to design feedback loops 1.2 Simulation for safety analysis: • Purpose: confirm that the nuclear station's design and operation during normal and emergency conditions will not lead to unacceptable excursions in physical parameters leading to equipment failure and risk to the public. Necessary to license plant design and operating mode. • Scope: all situations that may cause unsafe conditions. All systems that may cause such conditions. • Very complex representation of components and physical processes that could lead to public risk • Multiple independent programs for different systems, e.g. -

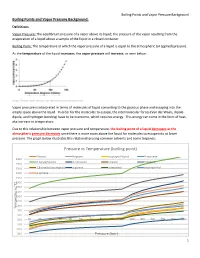

Pressure Vs Temperature (Boiling Point)

Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background: Definitions Vapor Pressure: The equilibrium pressure of a vapor above its liquid; the pressure of the vapor resulting from the evaporation of a liquid above a sample of the liquid in a closed container. Boiling Point: The temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid is equal to the atmospheric (or applied) pressure. As the temperature of the liquid increases, the vapor pressure will increase, as seen below: https://www.chem.purdue.edu/gchelp/liquids/vpress.html Vapor pressure is interpreted in terms of molecules of liquid converting to the gaseous phase and escaping into the empty space above the liquid. In order for the molecules to escape, the intermolecular forces (Van der Waals, dipole- dipole, and hydrogen bonding) have to be overcome, which requires energy. This energy can come in the form of heat, aka increase in temperature. Due to this relationship between vapor pressure and temperature, the boiling point of a liquid decreases as the atmospheric pressure decreases since there is more room above the liquid for molecules to escape into at lower pressure. The graph below illustrates this relationship using common solvents and some terpenes: Pressure vs Temperature (boiling point) Ethanol Heptane Isopropyl Alcohol B-myrcene 290.0 B-caryophyllene d-Limonene Linalool Pulegone 270.0 250.0 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) a-pinene a-terpineol terpineol-4-ol 230.0 p-cymene 210.0 190.0 170.0 150.0 130.0 110.0 90.0 Temperature (˚C) Temperature 70.0 50.0 30.0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 200 300 400 500 600 760 10.0 -10.0 -30.0 Pressure (torr) 1 Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background As a very general rule of thumb, the boiling point of many liquids will drop about 0.5˚C for a 10mmHg decrease in pressure when operating in the region of 760 mmHg (atmospheric pressure). -

Preliminary Geological Feasibility Report

R. L. LANGENHEfM, JR. EGN 111 DEPT. GEOL. UNIV. ILLINOIS 234 N.H. B., 1301 W. GREEN ST. URBANA, ILLINOIS 61801 Geological-Geotechnical Studies for Siting the Superconducting Super Collider in Illinois Preliminary Geological Feasibility Report J. P. Kempton, R.C. Vaiden, D.R. Kolata P.B. DuMontelle, M.M. Killey and R.A. Bauer Maquoketa Group Galena-Platteville Groups Illinois Department of Energy and Natural Resources ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY NOTES 111 STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIVISION 1985 Geological-Geotechnical Studies for Siting the Superconducting Super Collider in Illinois Preliminary Geological Feasibility Report J.P. Kempton, R.C. Vaiden, D.R. Kolata P.B. DuMontelle, M.M. Killey and R.A. Bauer ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Morris W. Leighton, Chief Natural Resources Building 615 East Peabody Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY NOTES 111 1985 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/geologicalgeotec1 1 1 kemp 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Superconducting Super Collider 1 Proposed Site in Illinois 2 Geologic and Hydrogeologic Factors 3 REGIONAL GEOLOGIC SETTING 5 Sources of Data 5 Geologic Framework 6 GEOLOGIC FRAMEWORK OF THE ILLINOIS SITE 11 General 1 Bedrock 12 Cambrian System o Ordovician System o Silurian System o Pennsylvanian System Bedrock Cross Sections 18 Bedrock Topography 19 Glacial Drift and Surficial Deposits 21 Drift Thickness o Classification, Distribution, and Description of the Drift o Banner Formation o Glasford Formation -

The Ideal Gas

LectureLecture 2222 Equations of state. The ideal gas. Kinetic model of a gas. Phase Diagram State variables State variables for a system: they characterize the system macroscopically at a given time. • Pressure • Temperature • Volume • Mass or moles Important: a system is in a thermal state that can be described by these variables when ALL the system has uniform pressure, temperature, etc. Example: Gas in a tube whose ends are kept at different temperature is NOT in a thermal state. Equation of state The equation of state relates the state variables. Can be obtained: • Empirically • From statistical mechanics The ideal gas An ideal gas is one whose molecules • are very small (point-like) • do not interact with one another This is very true for any gas that is not in an “extreme” situation. The gas is NOT ideal if we have: • high density • high pressure • near transition to liquid (or solid) • molecules are very large Mole of a gass A mole (mol) is defined as the number of grams of a substance that is numerically equal to the molecular mass of the substance: 1 mol of H2 has a mass of 2 g (2*1 protons + 2*0 neutrons per moleule) 1 mol of Ne has a mass of 20 g (1*10 protons + 1*10 neutrons per atom) 1 mol of O2 has a mass of 32 g (2*8 protons + 2*8 neutrons per molecule) 1 mol of C has a mass of 12 g (1*6 proton + 1*6 neutrons per atom) 1 mol of CO2 has a mass of 44 (1*6+2*8) protons + (1*6+2*8) neutrons per molecule mass Number of moles: n = molecular mass Q: How do I know the molecular mass? A: Look at the periodic table. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Problem Set #10 Assigned November 8, 2013 – Due Friday, November 15, 2013 Please Show All Work for Credit

Problem Set #10 Assigned November 8, 2013 – Due Friday, November 15, 2013 Please show all work for credit To Hand in 1. 1 2. –1 A least squares fit of ln P versus 1/T gives the result Hvaporization = 25.28 kJ mol . 3. Assuming constant pressure and temperature, and that the surface area of the protein is reduced by 25% due to the hydrophobic interaction: 2 G 0.25 N A 4 r Convert to per mole, ↓determine size per molecule 4 r 3 V M N 0.73mL/ g 60000g / mol (6.02 1023) 3 2 2 A r 2.52 109 m 2 23 9 2 G 0.25 N A 4 r 0.0720N / m 0.25 6.02 10 / mol (4 ) (2.52 10 m) 865kJ / mol We think this is a reasonable approach, but the value seems high 2 4. The vapor pressure of an unknown solid is approximately given by ln(P/Torr) = 22.413 – 2035(K/T), and the vapor pressure of the liquid phase of the same substance is approximately given by ln(P/Torr) = 18.352 – 1736(K/T). a. Calculate Hvaporization and Hsublimation. b. Calculate Hfusion. c. Calculate the triple point temperature and pressure. a) Calculate Hvaporization and Hsublimation. From Equation (8.16) dPln H sublimation dT RT 2 dln P d ln P dT d ln P H T 2 sublimation 11 dT dT R dd TT For this specific case H sublimation 2035 H 16.92 103 J mol –1 R sublimation Following the same proedure as above, H vaporization 1736 H 14.43 103 J mol –1 R vaporization b. -

Investigating How the Role of Pressure Is Misunderstood in the Process of Regelation of Water*

POCZYTAJMY PO ANGIELSKU Investigating how the role of pressure is misunderstood in the process of regelation of water*. Karim Daw Egypt Student of Vienna International School Vienna Nov. 2008* Introduction: The process of melting due to pressure and then re-freezing when pressure is reduced is commonly called regelation. There is a substantial amount of physics that is not clearly explained. The word "regelation" means re - freezing and does not imply that pressure plays any role in it. Congelare means “to freeze” in Italian. This essay reports on investigation to what extent pressure is responsible for regelation of water**. Aspects of thermal physics will come into play in this investigation, mainly, the effects of pressure on melting point. This is because observing the effects of pressure on a body involves understanding the transport of energy and where and how it is being transferred in the form of heat. The guiding research question is: To what extent does pressure play a role in the regelation of water. The process of regelation: When a substance turns from a solid to a liquid, it usually undergoes a change in volume as well. Most substances expand when this phase change takes place and some contract. In the case of water, it contracts when changing from solid to liquid. This is well expressed by Le Chatelier's** principles: "If a dynamic equilibrium is disturbed by changing the conditions, the position of equilibrium moves to counteract the change." When there is an application of pressure on ice, the system counteracts by lowering the pressure on it in some way. -

Chapter Two Properties of Ammonia

Chapter Two Properties of Ammonia Physical Properties General Anhydrous ammonia exists as either a colorless gas, colorless liquid, or white solid, depending on its pressure and temperature. In nearly all commonly encountered situations, it exists as either a liquid or a gas. The gas is less dense than air and the liquid is less dense than water at standard conditions. Ammonia gas (vapor) diffuses readily in air and the liquid is highly soluble in water with an accompanying release of heat. Ammonia exhibits classical saturation relationships whereby pressure and temperature are directly related so long as both the vapor and liquid phase are present. It does have a critical pressure and temperature. At atmospheric pressure, a closed container of ammonia vapor and liquid will be in equilibrium at a temperature of –28°F [–33°C]. It should be noted however that if liquid ammonia is spilled or released to the atmosphere at normal temperatures, the resultant pool of boiling liquid will be significantly colder than –28°F due to the law of partial pressures (the partial pressure of the ammonia vapor in the air near the liquid surface will be less than atmospheric pressure). The following table provides some of the important physical properties of ammonia. TABLE 2-1 Physical Properties of Ammonia Property Condition Value (IP) Value (SI) Molecular Weight 17.03 17.03 Color None None Physical State Room Temp Gas Gas Freezing Point P=1 atm –108°F –78°C Boiling Point P=1 atm –28.1°F –33.3°C Critical Pressure 1657 psia 11,410 kPa Critical Temp 271°F